China and India

Total Page:16

File Type:pdf, Size:1020Kb

Load more

Recommended publications

-

Bathinda 12000 Jagsir Singh S/O Dev S/O Darshan Singh Singh 23 Kulwant Talwandi Talwandi 12000 Jagsir Singh Singh S/O Sabo Sabo S/O Darshan Krishan Singh Singh

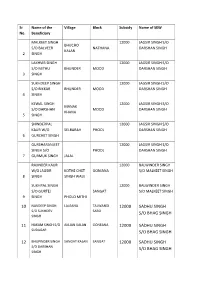

Sr Name of the Village Block Subsidy Name of SEW No. Beneficiary MALKEET SINGH 12000 JAGSIR SINGH S/O BHUCHO S/O BALVEER NATHANA DARSHAN SINGH KALAN 2 SINGH LAKHVIR SINGH 12000 JAGSIR SINGH S/O S/O MITHU BHUNDER MOOD DARSHAN SINGH 3 SINGH SUKHDEEP SINGH 12000 JAGSIR SINGH S/O S/O BIKKAR BHUNDER MOOD DARSHAN SINGH 4 SINGH KEWAL SINGH 12000 JAGSIR SINGH S/O MANAK S/O DARSHAN MOOD DARSHAN SINGH KHANA 5 SINGH SHINDERPAL 12000 JAGSIR SINGH S/O KAUR W/O SELBARAH PHOOL DARSHAN SINGH 6 GURCHET SINGH GURSHARANJEET 12000 JAGSIR SINGH S/O SINGH S/O PHOOL DARSHAN SINGH 7 GURMUK SINGH JALAL RAJINDER KAUR 12000 BALWINDER SINGH W/O JAGSIR KOTHE CHET GONIANA S/O MALKEET SINGH 8 SINGH SINGH WALE SUKHPAL SINGH 12000 BALWINDER SINGH S/O GURTEJ SANGAT S/O MALKEET SINGH 9 SINGH PHOLO MITHI 10 NAVDEEP SINGH LALEANA TALWANDI 12000 SADHU SINGH S/O SUKHDEV SABO S/O BHAG SINGH SINGH 11 HAKAM SINGH S/O AKLIAN KALAN GONEANA 12000 SADHU SINGH SUDAGAR S/O BHAG SINGH 12 BHUPINDER SINGH SANGAT KALAN SANGAT 12000 SADHU SINGH S/O DARSHAN S/O BHAG SINGH SINGH 13 BHUPINDER SINGH BHAGTA BHAGTA 12000 SADHU SINGH S/O NIRBHAI S/O BHAG SINGH SINGH 14 GURNAM SINGH JANDA WALA GONEANA 12000 SADHU SINGH S/O DALIP SINGH S/O BHAG SINGH 15 SURJIT SINGH S/O MALKANA TALWANDI 12000 AMARJEET SINGH GANDA SINGH SABO S/O GURDIAL SINGH 16 TARSEM SINGH MALKANA TALWANDI 12000 AMARJEET SINGH S/O GURDARSHAN SABO S/O GURDIAL SINGH SINGH 17 HARMESH SINGH GEHLEWALA TALWANDI 12000 HARBANS SINGH S/O GURBACHAN SABO S/O HARDIAL SINGH SINGH 18 JAGJEET SINGH GUMTI PHOOL 12000 JAGSIR SINGH S/O BASANT KALAN -

Sn Village Name Hadbast No. Patvar Area Kanungo Area 1991 2001

DISTT. HOSHIAR PUR KANDI/SUB-MOUNTAIN AREA POPULATION POPULATION SN VILLAGE NAME HADBAST NO. PATVAR AREA KANUNGO AREA 1991 2001 12 3 4 5 6 7 Block Hoshiarpur-I 1 ADAMWAL 370 ADAMWAL HOSHIARPUR 2659 3053 2 AJOWAL 371 ADAMWAL HOSHIARPUR 1833 2768 3 SAINCHAN 377 BHAGOWAL HOSHIARPUR 600 729 4 SARAIN 378 BHAGOWAL HOSHIARPUR 228 320 5 SATIAL 366 BASSI KIKRAN JAHAN KHELAN 328 429 6 SHERPUR BAHTIAN 367 CHOHAL HOSHIARPUR 639 776 7 KAKON 375 KAKON HOSHIARPUR 1301 1333 8 KOTLA GONSPUR 369 KOTLA GAUNS PUR HOSHIARPUR 522 955 9 KOTLA MARUF JHARI 361 BAHADAR PUR HOSHIARPUR 131 7 10 KANTIAN 392 KANTIAN HOSHIARPUR 741 1059 11 KHOKHLI 383 BHAGOWAL HOSHIARPUR 162 146 12 KHUNDA 395 BHEKHOWAL HOSHIARPUR 138 195 13 CHAK SWANA 394 KANTIAN HOSHIARPUR 121 171 KANDI-HPR.xls Hoshiarpur 1 DISTT. HOSHIAR PUR KANDI/SUB-MOUNTAIN AREA POPULATION POPULATION SN VILLAGE NAME HADBAST NO. PATVAR AREA KANUNGO AREA 1991 2001 14 THATHAL 368 KOTLA GAUNS PUR HOSHIARPUR 488 584 15 NUR TALAI 393 BHEKHOWAL HOSHIARPUR 221 286 16 BAGPUR 382 BAG PUR HOSHIARPUR 1228 1230 17 BANSARKAR URF NAND 364 BASSI GULAM HUSSA JAHAN KHELAN 632 654 18 BASSI GULAM HUSSAIN 362 BASSI GULAM HUSSAIN JAHAN KHELAN 2595 2744 19 BASSI KHIZAR KHAN 372 NALOIAN HOSHIARPUR 71 120 20 BASSI KIKRAN 365 BASSI KIKRAN JAHAN KHELAN 831 1096 21 BASSI MARUF HUSSAI 380 KANTIAN HOSHIARPUR 1094 1475 22 BASSI-MARUF SIALA 381 BHEKHOWAL HOSHIARPUR 847 1052 23 BASSI PURANI 363 BASSI GULAM HUSSA JAHAN KHELAN 717 762 24 BASSI KASO 384 KANTIAN HOSHIARPUR 238 410 25 BHAGOWAL JATTAN 379 BHAGOWAL HOSHIARPUR 418 603 26 BHIKHOWAL 391 BHEKHOWAL HOSHIARPUR 1293 1660 27 KOTLA NAUDH SINGH 143 KOTLA NODH SINGH BULLOWAL 611 561 28 BASSI BALLO 376 KAKON HOSHIARPUR 53 57 KANDI-HPR.xls Hoshiarpur 2 DISTT. -

Franchisee Area

FRANCHISEES DATA (Punjab LSA) UPDATED Upto 31.03.2021 S.No. Name of Franchisee (M/s) Address SSA Type (Distributor/ Area/ Wheather Area of Operation of territory Wheather through Contact Person Contact no Email id Type of Services retailer/ own outlet) Terrtiory/ through EOI/ EOI/ Migration/ (Prepaid/ Franchisee Zone Code Migration/ Lookafter Postpaid/ Both) Lookafter 1 EOI AJNALA (AJNALA U, Migrated js.milanagencies@gm Both Opp. AB palace, Near Radha Swami Milan Agencies Amritsar Franchisee ASR-01 BACHIWIND, BEHARWAL, Jasjeet Sethi 9464777770 ail.com Dera, Ram Tirath Road,Amritsar BHILOWAL, CHAMIARI, 2 EOI Albert Road, BATALA Road, Migrated js.milanagencies@gm Both Milan Agencies 39,the mall Amritsar Amritsar Franchisee ASR-02 Majitha Road-II, RANJIT Jasjeet Sethi 947803575 ail.com AVENUE, JAIL ROAD, VERKA 3 Migrated City (Katra Sher Singh, Tarn Migrated js.uscomputers@gmai Both U.S.Comp.Products 77, Hall Bazar, Amritsar Amritsar Franchisee ASR-03 Taran Road-II, Bhagtanwala) Jasjeet Sethi 9463393947 l.com 4 EOI JANDIALA (AKALGARH,BAL Migrated chanienterprises@yo Both 12,Baba Budha ji Avenue, G.T.Road, Avtar Singh Chani Enterprises Amritsar Franchisee ASR-04 KHURD,BHANGALI KALAN, 9417553366 ur.com Amritsar Chani BUNDALA, 5 EOI Tarn Taran (BATH, BUCHAR Migrated chanienterprises@yo Both Avtar Singh Chani Enterprises Tur Market, Tarn taran Amritsar Franchisee ASR-05 KHURD, CHABAL, CHEEMA 9530553536 ur.com Chani KHURD, DABURJI, DHAND 6 EOI PATTI (ALGON KOTHI, Migrated js.uscomputers@gmai Both Near amardeep palace old Kairon road U.S.Comp.Products Amritsar Franchisee ASR-06 AMARKOT, BASARKE, Jasjeet Sethi 9465272988 l.com ,Patti BHANGALA, BHIKHIWIND U, 7 Empowered RAYYA (BABA BAKALA, BAGGA, New abhinavsharma007@ Both VPO Rayya ,Tehsil Baba Bakala,Distt C.K. -

E3 Fh Fhft Meha (A.Fh) Afszt

E3 fH fHfT mEHa (A.fH) afszT HHU Ho HHÍ HJH/HHH} HA afos dse -SLA elkno28 fr 31/05/2021 fe-SLA zaföa Hstt euda fe Hau SCERT 6B7 SCERT/SCI/2021 22/2021170660f+t 28/05/2021 MaHG MA. E. SH n5 TEa FT OT fst 01/ ga/2021 a 02/H6/2021 aa argt FHT 9:30AM 3 12:30PM JEaTI H H st HUS fos f5tT 05 Ha% TU HHE JT SLA (Hfos) 1. fa tua 3 ad SLA whatsapp group fea HTH TET uatat aarfe Tatst asreI 3. 200M APP msz a et HrI 6. Z0OM APP äfars aaè HÀ MT 5H musz aa fwr aT 7. Z0OM APP 3 2f$ar föa 30 ffz ufr sn fts HaT| SLA as on Sr no. Edu Block Name 26.05.2021 School Name/Office 1 BATHINDA GSSS JODHPUR ROMANA Name Mobile No. | kanwaljeet kaur BATHINDA DES RAJ MEM GSSS BATHINDA 9417238341| Boys AMANDEEP KAUR 9915116537 BATHINDA DES RAJ MEM GSSS BATHINDA Boys BALVIR KAUR 9217252848 4 BATHINDA |DES RAJ MEM GSSS BATHINDA Boys HARINDER SINGH BATHINDA GSSS MULTANIA 9815091720 BATHINDA Karamjit Singh GSSS GULABGARH GURBINDER SINGH 9417439547 BATHINDA GSSS PARASRAM NAGAR BTD 7696612656 8 BATHINDA JASWINDER SINGH 9478881225 GSSS PARASRAM NAGAR BTD |Karmjit kaur BATHINDA GSSS SIVIAN 9463835758| Parmjit Kaur 10 BATHINDDA GSSS BALLUANA 9478772972| 11 BATHINDA GSSS Yogesh Kumar 9878911334| PARASRAM NAGAR BTD RUPINDER PAL SINGH BATHINDA GSSS KOT SHAMIR 9417109929| 13 BATHINDA AMREEK SINGH 9464151511| GSSS BEHMAN DIWANA KAMAL KANT SHAHEED MAJOR RAVI INDER 9417036855 14 BATHINDA SINGH SANDHU GSSS MALL ROAD GIRLS BATHINDA Patwinder Singh 9464100036 15 BHAGTA BHAI KA GSSS BHAGTA SUKHCHAIN SINGH 16 BHAGTA BHAI KA GSSS DHAPPALI 9501335682| BHAGTA Sunil Kumar 17 BHAI KA GSSS MALUKA -

Pincode Officename Statename Minisectt Ropar S.O Thermal Plant

pincode officename districtname statename 140001 Minisectt Ropar S.O Rupnagar PUNJAB 140001 Thermal Plant Colony Ropar S.O Rupnagar PUNJAB 140001 Ropar H.O Rupnagar PUNJAB 140101 Morinda S.O Ropar PUNJAB 140101 Bhamnara B.O Rupnagar PUNJAB 140101 Rattangarh Ii B.O Rupnagar PUNJAB 140101 Saheri B.O Rupnagar PUNJAB 140101 Dhangrali B.O Rupnagar PUNJAB 140101 Tajpura B.O Rupnagar PUNJAB 140102 Lutheri S.O Ropar PUNJAB 140102 Rollumajra B.O Ropar PUNJAB 140102 Kainaur B.O Ropar PUNJAB 140102 Makrauna Kalan B.O Rupnagar PUNJAB 140102 Samana Kalan B.O Rupnagar PUNJAB 140102 Barsalpur B.O Ropar PUNJAB 140102 Chaklan B.O Rupnagar PUNJAB 140102 Dumna B.O Ropar PUNJAB 140103 Kurali S.O Mohali PUNJAB 140103 Allahpur B.O Mohali PUNJAB 140103 Burmajra B.O Rupnagar PUNJAB 140103 Chintgarh B.O Rupnagar PUNJAB 140103 Dhanauri B.O Rupnagar PUNJAB 140103 Jhingran Kalan B.O Rupnagar PUNJAB 140103 Kalewal B.O Mohali PUNJAB 140103 Kaishanpura B.O Rupnagar PUNJAB 140103 Mundhon Kalan B.O Mohali PUNJAB 140103 Sihon Majra B.O Rupnagar PUNJAB 140103 Singhpura B.O Mohali PUNJAB 140103 Sotal B.O Rupnagar PUNJAB 140103 Sahauran B.O Mohali PUNJAB 140108 Mian Pur S.O Rupnagar PUNJAB 140108 Pathreri Jattan B.O Rupnagar PUNJAB 140108 Rangilpur B.O Rupnagar PUNJAB 140108 Sainfalpur B.O Rupnagar PUNJAB 140108 Singh Bhagwantpur B.O Rupnagar PUNJAB 140108 Kotla Nihang B.O Ropar PUNJAB 140108 Behrampur Zimidari B.O Rupnagar PUNJAB 140108 Ballamgarh B.O Rupnagar PUNJAB 140108 Purkhali B.O Rupnagar PUNJAB 140109 Khizrabad West S.O Mohali PUNJAB 140109 Kubaheri B.O Mohali PUNJAB -

Cornell University

April 2020 ESWAR S. PRASAD Nandlal P. Tolani Senior Professor of Trade Policy & Professor of Economics Cornell University Dyson School of Applied Economics and Management 301A Warren Hall, Ithaca, NY 14853 Email: eswar [dot] prasad [at] cornell [dot] edu Website: http://prasad.dyson.cornell.edu Concurrent Positions and Affiliations Professor of Economics, Cornell University (joint appt. with Department of Economics) Senior Fellow and New Century Chair in International Economics, Brookings Institution, Washington, DC Research Associate, National Bureau of Economic Research, Cambridge, MA Research Fellow, IZA (Institute for the Study of Labor), Bonn, Germany Founding Fellow, Emerging Markets Institute, Johnson School of Business, Cornell University Education Ph.D., Economics, University of Chicago, 1992 Thesis: “Employment, Wage, and Productivity Dynamics in an Equilibrium Business Cycle Model with Heterogeneous Labor” Supervised by Professors Robert E. Lucas, Jr., Robert M. Townsend and Michael Woodford M.A., Economics, Brown University, 1986 B.A., Economics, Mathematics, and Statistics, University of Madras, 1985 Employment Senior Fellow and New Century Chair, Brookings Institution, 2008-present Tolani Senior Professor of Trade Policy, Cornell University, 2007-present Division Chief, Financial Studies Division, Research Department, IMF, 2005-2006 Division Chief, China Division, Asia and Pacific Department, IMF, 2002-2004 Economist (1990-1998), Senior Economist (1998-2000), Assistant to the Director (2000- 2002), IMF Professional Experience Head of IMF’s China Division (2002-2004) and Financial Studies Division (2005-2006). Mission Chief for IMF Article IV Consultation missions to Myanmar (2002) and Hong Kong (2003-04). Member of the analytical team for the High-Level Committee on Financial Sector - 2 - Reforms appointed by the Planning Commission, Government of India, 2007-08 (Chairman: Raghuram Rajan). -

(OH) Category 1 30 Ranjit Kaur D/O V.P.O

Department of Local Government Punjab (Punjab Municipal Bhawan, Plot No.-3, Sector-35 A, Chandigarh) Detail of application for the posts of Beldar, Mali, Mali-cum-Chowkidar, Mali -cum-Beldar-cum- Chowkidar and Road Gang Beldar reserved for Disabled Persons in the cadre ofMunicipal Corporations and Municipal Councils-Nagar Panchayats in Punjab Sr. App Name of Candidate Address Date of Birth VH, HH, OH No. No. and Father’s Name etc. %age of Sarv Shri/ Smt./ Miss disability 1 2 3 4 5 6 Orthopedically Handicapped (OH) Category 1 30 Ranjit Kaur D/o V.P.O. Depur, Hoshiarpur 15.02.1983 OH 60% Swarn Singh 2 32 Rohit Kumar S/o Vill. Bhavnal, PO Sahiana, 27.05.1982 OH 60% Gian Chand Teh. Mukerian, Distt. Hoshiarpur, Punjab. 3 93 Nitish Sharma S/o Vill. Talwara, Distt. 22.05.1989 OH 50% Jeewan Kumar Hoshiarpur, Punjab. 4 100 Sukhwinder Singh V.P.O. Amroh, Teh. 31.03.1999 OH 70% S/o Gurmit Singh Mukerian, Distt. Hoshiarpur, Punjab. 5 126 Charanjeet Singh S/o V.P.O. Lamin, Teh. Dasuya, 13.11.1995 OH 50% Ram Lal Distt. Hoshiarpur, Punjab. 6 152 Ravinder Kumar S/o Vill. Allo Bhatti, P.O. Kotli 05.03.1979 OH 40% Gian Chand Khass, Teh. Mukerian, Distt. Hoshiarpur, Punjab. 7 162 Narinder Singh S/o Vill. Jia Sahota Khurd. P.O. 13.09.1983 OH 60% Santokh Singh Gardhiwala, Distt. Hoshiarpur, Punjab. 8 177 Bhupinder Puri S/o V.P.O. Nainwan, Teh. 09.05.1986 OH 40% Somnath Garhshankar, Distt. Hoshiarpur, Punjab. 9 191 Sohan Lal S/o Nasib Vill. -

A Pragmatic Approach to Capital Account Liberalization

NBER WORKING PAPER SERIES A PRAGMATIC APPROACH TO CAPITAL ACCOUNT LIBERALIZATION Eswar S. Prasad Raghuram Rajan Working Paper 14051 http://www.nber.org/papers/w14051 NATIONAL BUREAU OF ECONOMIC RESEARCH 1050 Massachusetts Avenue Cambridge, MA 02138 June 2008 We are grateful to James Hines and Jeremy Stein for very useful comments and to Timothy Taylor for helping us sharpen the exposition. Yusuke Tateno provided excellent research assistance. The views expressed herein are those of the author(s) and do not necessarily reflect the views of the National Bureau of Economic Research. NBER working papers are circulated for discussion and comment purposes. They have not been peer- reviewed or been subject to the review by the NBER Board of Directors that accompanies official NBER publications. © 2008 by Eswar S. Prasad and Raghuram Rajan. All rights reserved. Short sections of text, not to exceed two paragraphs, may be quoted without explicit permission provided that full credit, including © notice, is given to the source. A Pragmatic Approach to Capital Account Liberalization Eswar S. Prasad and Raghuram Rajan NBER Working Paper No. 14051 June 2008 JEL No. F21,F31,F36,F43 ABSTRACT Cross-country regressions suggest little connection from foreign capital inflows to more rapid economic growth for developing countries and emerging markets. This suggests that the lack of domestic savings is not the primary constraint on growth in these economies, as implicitly assumed in the benchmark neoclassical framework. We explore emerging new theories on both the costs and benefits of capital account liberalization, and suggest how one might adopt a pragmatic approach to the process.¸ Eswar S. -

Repair Programme 2018-19 Administrative Detail of Repair Approval Sr

Repair Programme 2018-19 Administrative Detail of Repair Approval Sr. Name of Name Xen/Mobile No. Distt. MC Name of Work Strengthe Premix No. Length Cost Raising Contractor/Agency Name of SDO/Mobile No. ning Carepet in in Km. in lacs in Km in Km Km 1 2 3 4 5 6 7 8 9 10 11 M/s Parduman Singh & Er.Pawan Kumar / 9780000084 1 Hoshiarpur Mukerian NHIA to Dasuya Hajipur Road 16.96 186.44 3.03 5.11 16.96 Co. [Gr.No.1] Er.Davinder Kumar / 9478734720 M/s Parduman Singh & Er.Pawan Kumar / 9780000084 2 Hoshiarpur Mukerian Mukerian to Dasuya Hajipur road 10.65 130.85 1.68 2.35 10.65 Co. [Gr.No.2] Er.Davinder Kumar / 9478734720 Mukerian Hajipur road to Dallowal & link M/s Parduman Singh & Er.Pawan Kumar / 9780000084 3 Hoshiarpur Mukerian 0.5 6.33 0.04 0.38 0.5 to Phirni of vill. Dallowal Co. [Gr.No.2] Er.Davinder Kumar / 9478734720 M/s Parduman Singh & Er.Pawan Kumar / 9780000084 4 Hoshiarpur Mukerian Mukerian Hajipur road to Ralli 1.42 16.87 0.44 0.17 1.42 Co. [Gr.No.2] Er.Davinder Kumar / 9478734720 M/s Parduman Singh & Er.Pawan Kumar / 9780000084 5 Hoshiarpur Mukerian Mukerian Hajipur road to Jahidpur 0.5 5.98 -- 0.3 0.5 Co. [Gr.No.2] Er.Davinder Kumar / 9478734720 Mukerian Hajipur road to Dallowal & link M/s Parduman Singh & Er.Pawan Kumar / 9780000084 6 Hoshiarpur Mukerian 1.2 16.34 0.2 0.81 1.2 to Phirni of vill. -

Punjab Medical Council Electoral Rolls Upto 31-01-2018

Punjab Medical Council Electoral Rolls upto 31-01-2018 S.No. Name/ Father Name Qualification Address Date of Registration Validity Registration Number 1. Dr. Yash Pal Bhandari S/o L.M.S.F. 1948 81, Vijay Nagar, Jalandhar 12.04.1948 45 22.10.2018 Sh. Ram Krishan M.B.B.S. 1961 M.D. 1965 2. Dr. Balwant Singh S/o LSMF 1952 1814, Maharaj nagar, Near Gate No.3, 28.10.1952 3266 17.03.2021 Sh. Suhawa Singh M.B.B.S. 1964 of P.A.U., Ludhiana 3. Dr. Kanwal Kishore Arora S/o M.B.B.S. 1952 392, Adarsh Nagar Jalandhar 15.12.1952 3312 09.03.2019 Sh. Lal Chand Pasricha 4. Dr. Gurbax Singh S/o LSMF 1952 B-5/442, Kulam Road, Tehsil 11.03.1953 3396 23.04.2019 Sh. Mangal Singh M.B.B.S. 1956 Nawanshahr Distt. SBS Nagar D.O. 1957 5. Dr. Jawahar Lal Luthra L.S.M.F. 1953 H.No.44, Sector 11-A, Chandigarh 27.10.1953 3555 07.10.2018 M.B.B.S. 1956 M.S. (Ophth.) 1970 6. Dr. Kirpal Kaur M.B.B.S. 1953 490, Basant Avenue, Amritsar 09.12.1953 3599 31.03.2019 M.D. 1959 7. Dr. Harbans Kaur Saini L.S.M.F. 1954 Railway Road, Nawan Shahr Doaba 31.05.55 4092 29.01.2019 8. Dr. Baldev Raj Bhateja L.S.M.F. 1955 Raj Poly Clinic and Nursing Home, Pt. 08-06-1955 4106 09.10.2018 Jai Dayal St., Muktsar. -

Village & Townwise Primary Census Abstract, Bathinda, Part XIII a & B

CENSUS 1981 SERIES 17 VILLAGE & TOWN DIRECTORY PUNJAB VILLAGE & TOWNWISE PRIMARY CENSUS ABSTRACT BATHINDA DISTRICT DISTRICT CENSUS HANDBOOK D. N. OHIR OF THE INDIAN ADMINisTRATIvE SERVICa DIRECTOR OF CENSUS OPERATIONS PUNJAB ----------------; 10 d '" y.. I 0 B i i© ~ 0 :c « :I:'" :I: l- I :!. :I: 1 S z VI "- Ir .t:. 0 III 0 i i I@ 11 Z If i i I l l I ~ 2 m 0 0 UJ 0 u.j ~ >' g: g: .. ~ -,'" > .. g U '" iii 2 « V1 0 ",' ..'" ..' (() 2 ~ <;;''" ~ .. - I 0 LL ~ ) w m '" .. 0 :> 2 0 i 0: <l <l ;: .. iii "- 9 '" ~ 0 I Z !? I- 0 l- 0 ~ <l Z UJ "- 0 I- 0: l- t- 0 ::I: :'\ z u Vl <II r oz ~ :::> :> "- 20 o!;i I <l I I 0: 0 <{ 0 0-' S I- "- I- I <l>' II) ii 0 0 3: ,.." VI ;:: t- Ir 0::> 0... 0 0 0 U j <!) ::> ",,,- t> 3i "- 0 ~ 0 ;t g g g ;: 0 0 S 0: iii ,_« 3: ~ "'t: uJ 0 0' ~' ~. ",''" w '" I-- I ~ "'I- ","- U> (D VI I ~ Will 0: <t III <!) wW l!! Z 0:: S! a 0:: 3: ::I: "'w j~ .... UI 0 >- '" zt!> UJ :;w z., OJ 'i: ::<: z'"- « -<t 0 (/) '"0 WVl I-- ~ :J ~:> 0 «> "! :; >- 0:: I-- z u~ ::> ::<:0 :I: 0:,\ Vl - Ir i'" z « 0 m '" « -' <t I l- til V> « ::> <t « >- '" >- '" w'o' w« u ZO <t 0 z .... «0 Wz , 0 w Q; <lw u-' 2: 0 0 ~~ I- 0::" I- '" :> • "« =0 =1-- Vl (/) ~o ~ 5 "- <{w "'u ~z if> ~~ 0 W ~ S "'"<to: 0 WUJ UJ "Vl _e ••• · m r z II' ~ a:m 0::>: "- 01-- a: :;« is I _____ _ CENSUS OF INDIA-1981 A-CENTRAL GOVERNMENT PUBUCATIONS The 1981 Census Reports on Punjab will bear uniformly Series No. -

Eswar S. Prasad February 4, 2016

CHINA’S EFFORTS TO EXPAND THE INTERNATIONAL USE OF THE RENMINBI Eswar S. Prasad February 4, 2016 Report prepared for the U.S.-China Economic and Security Review Commission CHINA’S EFFORTS TO EXPAND THE INTERNATIONAL USE OF THE RENMINBI Eswar Prasad1 February 4, 2016 Disclaimer: This research report was prepared at the request of the U.S.-China Economic and Security Review Commission to support its deliberations. Posting of the report to the Commission's website is intended to promote greater public understanding of the issues addressed by the Commission in its ongoing assessment of U.S.-China economic relations and their implications for U.S. security, as mandated by Public Law 106-398 and Public Law 108-7. However, it does not necessarily imply an endorsement by the Commission or any individual Commissioner of the views or conclusions expressed in this commissioned research report. Disclaimer: The Brookings Institution is a private non-profit organization. Its mission is to conduct high- quality, independent research and, based on that research, to provide innovative, practical recommendations for policymakers and the public. The conclusions and recommendations of any Brookings publication are solely those of its author(s), and do not reflect the views of the Institution, its management, or its other scholars. 1 Cornell University, Brookings Institution, and NBER. The author is grateful to members and staff of the Commission for their thoughtful and constructive comments on an earlier draft of this report. Audrey Breitwieser, Karim Foda, and Tao Wang provided excellent research assistance. William Barnett and Christina Golubski provided editorial assistance.