William Etty Ra (1787-1849)

Total Page:16

File Type:pdf, Size:1020Kb

Load more

Recommended publications

-

Classical Nakedness in British Sculpture and Historical Painting 1798-1840 Cora Hatshepsut Gilroy-Ware Ph.D Univ

MARMOREALITIES: CLASSICAL NAKEDNESS IN BRITISH SCULPTURE AND HISTORICAL PAINTING 1798-1840 CORA HATSHEPSUT GILROY-WARE PH.D UNIVERSITY OF YORK HISTORY OF ART SEPTEMBER 2013 ABSTRACT Exploring the fortunes of naked Graeco-Roman corporealities in British art achieved between 1798 and 1840, this study looks at the ideal body’s evolution from a site of ideological significance to a form designed consciously to evade political meaning. While the ways in which the incorporation of antiquity into the French Revolutionary project forged a new kind of investment in the classical world have been well-documented, the drastic effects of the Revolution in terms of this particular cultural formation have remained largely unexamined in the context of British sculpture and historical painting. By 1820, a reaction against ideal forms and their ubiquitous presence during the Revolutionary and Napoleonic wartime becomes commonplace in British cultural criticism. Taking shape in a series of chronological case-studies each centring on some of the nation’s most conspicuous artists during the period, this thesis navigates the causes and effects of this backlash, beginning with a state-funded marble monument to a fallen naval captain produced in 1798-1803 by the actively radical sculptor Thomas Banks. The next four chapters focus on distinct manifestations of classical nakedness by Benjamin West, Benjamin Robert Haydon, Thomas Stothard together with Richard Westall, and Henry Howard together with John Gibson and Richard James Wyatt, mapping what I identify as -

A Potterõ S Pots, by Suze Lindsay Clay Culture

Cover: Bryan Hopkins functional constructions Spotlight: A Potter s Pots, by Suze Lindsay Clay Culture: An Exploration of Jun ceramics Process: Lauren Karle s folded patterns em— robl ever! p a Mark Issenberg, Lookout M ” ountain d 4. Pottery, 7 Risin a 9 g Faw h 1 n, GA r in e it v t e h n g s u a o h b t I n e r b y M “ y t n a r r a w r a e y 10 (800) 374-1600 • www.brentwheels.com a ith el w The only whe www.ceramicsmonthly.org october 2012 1 “I have a Shimpo wheel from the 1970’s, still works well, durability is important for potters” David Stuempfle www.stuempflepottery.com 2 october 2012 www.ceramicsmonthly.org www.ceramicsmonthly.org october 2012 3 MONTHLY ceramic arts bookstore Editorial [email protected] telephone: (614) 794-5867 fax: (614) 891-8960 editor Sherman Hall associate editor Holly Goring associate editor Jessica Knapp editorial assistant Erin Pfeifer technical editor Dave Finkelnburg online editor Jennifer Poellot Harnetty Advertising/Classifieds [email protected] telephone: (614) 794-5834 fax: (614) 891-8960 classifi[email protected] telephone: (614) 794-5843 advertising manager Mona Thiel advertising services Jan Moloney Marketing telephone: (614) 794-5809 marketing manager Steve Hecker Subscriptions/Circulation customer service: (800) 342-3594 [email protected] Design/Production production editor Melissa Bury production assistant Kevin Davison design Boismier John Design Editorial and advertising offices 600 Cleveland Ave., Suite 210 Westerville, Ohio 43082 Publisher Charles Spahr Editorial Advisory Board Linda Arbuckle; Professor, Ceramics, Univ. -

Exhibitions & Events

Events for Adults at a Glance Forthcoming Exhibitions Pricing and online booking at yorkartgallery.org.uk. Discover more and buy tickets at yorkartgallery.org.uk. FREE TALKS – no need to book Grayson Perry: The Pre-Therapy Years EXHIBITIONS Opens 12 June 2020 Curator’s Choice The first exhibition to & EVENTS Third Wednesday of the month: 12.30pm – 1pm. survey Grayson Perry’s earliest forays into the art February – May 2020 Friends of York Art Gallery Lunchtime Talks world will re-introduce the Second Wednesday of the month: 12.30pm – 1pm. explosive and creative 14 Feb – 31 May 2020 works he made between Plan your visit… Visitor Experience Team Talks 1982 and 1994. These Every day between 2pm – 3pm (except Wednesday ground-breaking ‘lost’ pots OPEN DAILY: 10am – 5pm and Saturday). will be reunited for the first time to focus on the York Art Gallery York Art Gallery is approximately Kindly Supported by Automaton Clock Talk and Demonstration Exhibition Square, York YO1 7EW 15 minutes walk from York Railway formative years of one of T: 01904 687687 Station. From the station, cross the Harland Miller, Ace, 2017. © Harland Miller. Photo © White Cube (George Darrell). Wednesday and Saturday: 2pm – 2.30pm. Britain’s most recognisable E: [email protected] river and walk towards York Minster. artists. The nearest car parks are Bootham Row and Marygate, which are a five WORKSHOPS – book online Touring exhibition from minute walk from York Art Gallery. The Holburne Museum Aesthetica Art Prize 2020 Tickets can be purchased in advance or on arrival. For pricing and to book your Sketchbook Circle Image: Grayson Perry, Cocktail Party, 1989 © Grayson Perry. -

Review of the Year 2012–2013

review of the year TH E April 2012 – March 2013 NATIONAL GALLEY TH E NATIONAL GALLEY review of the year April 2012 – March 2013 published by order of the trustees of the national gallery london 2013 Contents Introduction 5 Director’s Foreword 6 Acquisitions 10 Loans 30 Conservation 36 Framing 40 Exhibitions 56 Education 57 Scientific Research 62 Research and Publications 66 Private Support of the Gallery 70 Trustees and Committees of the National Gallery Board 74 Financial Information 74 National Gallery Company Ltd 76 Fur in Renaissance Paintings 78 For a full list of loans, staff publications and external commitments between April 2012 and March 2013, see www.nationalgallery.org.uk/about-us/organisation/ annual-review the national gallery review of the year 2012– 2013 introduction The acquisitions made by the National Gallery Lucian Freud in the last years of his life expressed during this year have been outstanding in quality the hope that his great painting by Corot would and so numerous that this Review, which provides hang here, as a way of thanking Britain for the a record of each one, is of unusual length. Most refuge it provided for his family when it fled from come from the collection of Sir Denis Mahon to Vienna in the 1930s. We are grateful to the Secretary whom tribute was paid in last year’s Review, and of State for ensuring that it is indeed now on display have been on loan for many years and thus have in the National Gallery and also for her support for very long been thought of as part of the National the introduction in 2012 of a new Cultural Gifts Gallery Collection – Sir Denis himself always Scheme, which will encourage lifetime gifts of thought of them in this way. -

Pre-Raphaelite Aesthetics As the Antidote for Victorian Decadence in Robert Browning’S “My Last Duchess”

Channels: Where Disciplines Meet Volume 1 Number 2 Spring 2017 Article 1 May 2017 Encountering the Phantasmagoria: Pre-Raphaelite Aesthetics as the Antidote for Victorian Decadence in Robert Browning’s “My Last Duchess” Matthew K. Werneburg Cedarville University, [email protected] Follow this and additional works at: https://digitalcommons.cedarville.edu/channels Part of the Catholic Studies Commons, Fine Arts Commons, Literature in English, British Isles Commons, and the Theory and Criticism Commons DigitalCommons@Cedarville provides a publication platform for fully open access journals, which means that all articles are available on the Internet to all users immediately upon publication. However, the opinions and sentiments expressed by the authors of articles published in our journals do not necessarily indicate the endorsement or reflect the views of DigitalCommons@Cedarville, the Centennial Library, or Cedarville University and its employees. The authors are solely responsible for the content of their work. Please address questions to [email protected]. Recommended Citation Werneburg, Matthew K. (2017) "Encountering the Phantasmagoria: Pre-Raphaelite Aesthetics as the Antidote for Victorian Decadence in Robert Browning’s “My Last Duchess”," Channels: Where Disciplines Meet: Vol. 1 : No. 2 , Article 1. DOI: 10.15385/jch.2017.1.2.1 Available at: https://digitalcommons.cedarville.edu/channels/vol1/iss2/1 Encountering the Phantasmagoria: Pre-Raphaelite Aesthetics as the Antidote for Victorian Decadence in Robert Browning’s “My Last Duchess” Abstract Robert Browning’s “My Last Duchess” engages with ‘the problem of Raphael,’ a Victorian aesthetic debate into which Browning enters in order to address Victorian society’s spiritual impotence, which he connects to the societal emphasis on external appearances of virtue and nobility. -

Exhibitions & Events

Events for Adults at a Glance Forthcoming Exhibitions Pricing and online booking at yorkartgallery.org.uk. Discover more and buy tickets at yorkartgallery.org.uk. Exhibitions FREE TALKS – no need to book Harland Miller: York, So Good They Named It Once Curator’s Choice 14 February – 31 May 2020 & Events Third Wednesday of the month: 12.30pm – 1pm. York Art Gallery presents a mid-career exhibition of York- Friends of York Art Gallery Lunchtime Talks born artist Harland Miller. The largest solo presentation October 2019 – January 2020 of his work to date, it celebrates his relationship to the Second Wednesday of the month: 12.30pm – 1pm. city of his upbringing. Alongside more recent works, Plan your visit… Visitor Experience Team Talks it will feature a selection of Miller’s acclaimed classic Penguin series and ‘bad weather paintings’ which playfully Every day between 2pm – 3pm (except Wednesday Dieric Bouts (c.1415 – 1475), Christ Crowned with Thorns, c.1470 © The National Gallery, London. reference various cities in the North of England, evoking and Saturday). OPEN DAILY: 10am – 5pm Bequeathed by Mrs Joseph H. Green, 1880 a tragicomic sense of time and place. York Art Gallery York Art Gallery is approximately The Making a Masterpiece: Bouts and Beyond (1450 – 2020) exhibition has been made possible as a result of the Automaton Clock Talk and Demonstration Supported by White Cube Exhibition Square, York YO1 7EW 15 minutes walk from York Railway Government Indemnity Scheme. York Art Gallery would like to thank HM Government for providing Government T: 01904 687687 Station. From the station, cross the Indemnity and the Department for Digital, Culture, Media and Sport and Arts Council England for arranging the indemnity. -

Art the Friends of York Art Gallery Have Helped to Buy

Art The Friends of York Art Gallery Have Helped to Buy Year Art Work Title Artist York Art Gallery Reference 2018 Three Dark Glazed Pots Patrick Reed YORAG: 2018.5 -7 2018 Ceramic Dish Robert Brumby YORAG: 2018.4 2018 British American Scarecrow Mohamed Sami YORAG: 2018.42 2017 Double Stuart John Langton YORAG: 2017.7 2016 Twelve Apostles Loretta Braganza YORAG: 2016.4 2016 Lumber Room Jug Emily Sutton YORAG: 2016.37 2016 Noah's Ark Emily Sutton YORAG: 2016.38 2016 Riffli Austin Wright YORAG: 2017.28 2015 Melanie Grayson Perry YORAG: 2015.9 2015 Proposed Museum Garden Sculpture Park Patrick Hall YORAG:2014.4 2015 NUD4 Sarah Lucas YORAG: 2014.19.a-c. 2014 View of Exhibition Square Ed Kluz YORAG: 2014.16 2014 Tower of Pots Clare Twomey Not Applicable 2014 New Expressions Phil Eglin YORAG: 2015.15 2013 Passage and Paradise Lost Stephen Dixon YORAG: 2012.48.1-6 2013 Portrait of Mrs. Brookes Unknown YORAG: 2014.18 2012 Drawings Jules George YORAG: 2013.1.1 - 1.7 2011 The Anonymous Rose Simon Periton YORAG: 2011.1743 2011 Yellow Open Form Merete Rasmussen YORAG: 2011.1742 2010 Jar Emile Lenoble YORAG: 2010.1 2009 Preparing for a Fancy Dress Ball William Etty YORAG: 2009.6 2008 Oval Dish and 'Dovecote' Mike Eden YORAG: 2008.2 2008 Dovecote Paul Young YORAG: 2008.1 2008 Temperance "Toby Jug" Richard Slee YORAG: 2008.252 2008 Equanimity Chris Levine YORAG: 2009.2 2007 Dish Tomimoto Kenkichi YORAG: 2006.352 2007 Nine Portraits of the Cholmeley Family John Sell Cotman YORAG: 2006.1202-7 2006 York Minster from Stonemason's Yard John Varley YORAG: -

Exhibitions and Events

Events for Adults at a Glance Forthcoming Exhibitions Major New Exhibition Pricing and online booking at yorkartgallery.org.uk. Discover more and buy tickets at yorkartgallery.org.uk. Exhibitions FREE TALKS – no need to book Sounds Like Her 12 July – 25 August 2019 Curator’s Choice Sounds Like Her is a touring exhibition produced by Third Wednesday of the month: 12.30pm – 1pm. and Events New Art Exchange (NAE). It brings together seven women artists, including Sonia Boyce MBE RA, from diverse Friends of York Art Gallery Lunchtime Talks backgrounds each exploring sound as a medium or March – June 2019 Second Wednesday of the month: 12.30pm – 1pm. subject matter in innovative ways. Plan your visit… Visitor Experience Team Talks JMW Turner, Constance, 1842, The National Gallery Masterpiece Tour 2019 watercolour © York Art Gallery. Every day between 2pm – 3pm (except Wednesday 12 July – 22 September 2019 and Saturday). OPEN DAILY: 10am – 5pm York Art Gallery are excited to be displaying The Triumph York Art Gallery York Art Gallery is approximately Automaton Clock Talk and Demonstration of Pan by Nicolas Poussin, one of the most important and Exhibition Square, York YO1 7EW 15 minutes walk from York Railway Ruskin, Turner influential painters of the 17th century. This display is part T: 01904 687687 Station. From the station, cross the Wednesday and Saturday: 2pm – 2.30pm. E: [email protected] river and walk towards York Minster. of The National Gallery Masterpiece Tour 2019 sponsored The nearest car parks are Bootham by Christie’s. Row and Marygate, which are a five & the Storm Cloud minute walk from York Art Gallery. -

British Taste in the Nineteenth Century ••

BRITISH TASTE IN THE NINETEENTH CENTURY •• WILLIAM MULREADY The Sailing Match (S l) BRITISH TASTE IN THE NINETEENTH CENTURY AUCKLAND CITY ART GALLERY • MAY 1962 Foreword This exhibition has been arranged for the 1962 Auckland Festival of Arts. We are particularlv grateful to all the owners of pictures who have been so generous with their loans. p. A. TOMORY Director Introduction This exhibition sets out to indicate the general taste of the nineteenth century in Britain. As only New Zealand collections have been used there are certain inevitable gaps, but the main aim, to choose paintings which would reflect both the public and private patronage of the time, has been reasonably accomplished. The period covered is from 1820 to 1880 and although each decade may not be represented it is possible to recognise the effect on the one hand of increasing middle class patronage and on the other the various attempts like the Pre-Raphaelite move ment to halt the decline to sentimental triviality. The period is virtually a history of the Royal Academy, which until 1824, when the National Gallery was opened, provided one of the few public exhibitions of paintings. Its influence, therefore, even late in the century, on the public taste was considerable, and artistic success could onlv be assured by the Academy. It was, however, the rise of the middle class which dictated, more and more as the century progressed, the type of art produced by the artists. Middle class connoisseur- ship was directed almost entirely towards contemporary painting from which it de manded no more than anecdote, moral, sentimental or humorous, and landscapes or seascapes which proclaimed ' forever England.' Ruskin, somewhat apologetically (On the Present State of Modern Art 1867), detected two major characteristics — Compassionateness — which he observed had the tendency of '. -

Exhibitions and Events

Exhibitions and Events SEPTEMBER 2018 – MARCH 2019 Exhibitions Highlights September 2018 – March 2019 Strata | Rock | Dust | Stars 28 September – 25 November 2018 OF Day of Clay DAY 6 October 2018 The BFG in Pictures 12 October 2018 – 24 February 2019 When all is Quiet: Kaiser Chiefs in CLAY Conversation with York Art Gallery 14 December 2018 – 10 March 2019 Lucie Rie: Ceramics and Buttons Until 12 May 2019 ARTIST’S CHOICE by Per Inge Bjørlo Until 31 March 2019 6 OCTOBER 2018 Project Gallery As part of the Ceramics + Design Now Festival 2018, join York Art Gallery for a celebration of ceramics with Ulungile Magubane, eMBIZENI hands-on activities, performance art, raku firing, workshops and expert talks. From 28 September 2018 Save time and buy your ticket online – visit yorkartgallery.org.uk | 3 Strata | Rock | Dust | Stars A York Museums Trust, FACT Liverpool, and York Mediale exhibition. 28 September – 25 November 2018 This is a landmark exhibition featuring moving image, new media and interactive artwork. Strata - Rock - Dust - Stars takes its inspiration from William Smith’s ground-breaking geological map of England, Wales and Scotland, created in 1815 – which identified the layers of the Earth and transformed the way in which the world was understood. It will be the most ambitious and large-scale media art exhibition York has ever hosted. The exhibition showcases works by internationally renowned artists Isaac Julien, Agnes Meyer-Brandis, Semiconductor, Phil Coy, Liz Orton, David Jacques, and Ryoichi Kurokawa. Co-commissioned between York Art Gallery and York Mediale, and curated by Mike Stubbs, Director of FACT Liverpool. -

Art, Anatomy and the Modern Male Body by Anthea Callen

Roberto C. Ferrari book review of Looking at Men: Art, Anatomy and the Modern Male Body by Anthea Callen Nineteenth-Century Art Worldwide 18, no. 2 (Autumn 2019) Citation: Roberto C. Ferrari, book review of “Looking at Men: Art, Anatomy and the Modern Male Body by Anthea Callen,” Nineteenth-Century Art Worldwide 18, no. 2 (Autumn 2019), https://doi.org/10.29411/ncaw.2019.18.2.10. Published by: Association of Historians of Nineteenth-Century Art Notes: This PDF is provided for reference purposes only and may not contain all the functionality or features of the original, online publication. License: This work is licensed under a Creative Commons Attribution-NonCommercial 4.0 International License Creative Commons License. Ferrari: Looking at Men: Art, Anatomy and the Modern Male Body by Anthea Callen Nineteenth-Century Art Worldwide 18, no. 2 (Autumn 2019) Anthea Callen, Looking at Men: Art, Anatomy and the Modern Male Body. New Haven and London: Yale University Press, 2018. 272 pp.; 212 b&w and color illus.; bibliography; index. $60.00 (hardcover) ISBN: 978-0-300-11294-8 Every art historian who specializes in the long nineteenth century has engaged at one point or another with the male nude in art, from the beau idéal figures of Jacques-Louis David’s history paintings to the abstracted bodies among Paul Cézanne’s bathers. Nevertheless, representation of the male nude in mainstream art, film, and social media remains controversial, its taboo nature often generating responses ranging from excitement to disgust to embarrassment. The male nude certainly has received less critical attention in art history than the female nude, which has been displayed, appreciated, and critiqued extensively, and analyzed with methods ranging from formalism to feminism. -

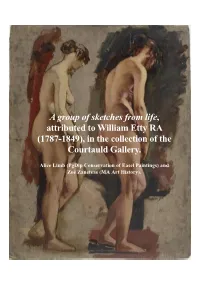

A Group of Sketches from Life, Attributed to William Etty RA (1787-1849), in the Collection of the Courtauld Gallery

A group of sketches from life, attributed to William Etty RA (1787-1849), in the collection of the Courtauld Gallery. Alice Limb (PgDip Conservation of Easel Paintings) and Zoë Zaneteas (MA Art History). Zoë Zaneteas and Alice Limb Painting Pairs 2019 A group of sketches from life, attributed to William Etty RA (1787-1849), in the collection of the Courtauld Gallery. This report was produced as part of the Painting Pairs project and is a collaboration between Zoë Zaneteas (MA Art History) and Alice Limb (PgDip Conservation of Easel Paintings).1 Aims of the Project This project focusses on a group of seven sketches on board, three of which are double sided, which form part of the Courtauld Gallery collection. We began this project with three overarching aims: firstly, to contextualize the attributed artist, William Etty, within the artistic, moral and social circumstances of his time and revisit existing scholarship; secondly, to examine the works from a technical and stylistic perspective in order to establish if their attribution is justified and, if not, whether an alternative attribution might be proposed; finally, to treat one of the works (CIA2583), including decisions on whether the retention of material relating to the work’s early physical history was justified and if this material further informs our knowledge of Etty’s practice. It must be noted that Etty was a prolific artist during the forty years he was active, and that a vast amount of artistic and archival material (both critical and personal) relates to him. This study will 1 Special thanks must go to: the staff of the Courtauld Gallery (especially Dr Karen Serres, Kate Edmondson and Graeme Barraclough), the staff of the Department of Conservation and Technology (especially Clare Richardson, Dr Pia Gotschaller and Professor Aviva Burnstock), Dr Beatrice Bertram of York City Art Gallery, Jevon Thistlewood and Morwenna Blewett of the Ashmolean Museum, and the staff of the Royal Academy Library, Archives and Stores (especially Helen Valentine, Annette Wickham, Mark Pomeroy, and Daniel Bowman).