Pre-Raphaelite Aesthetics As the Antidote for Victorian Decadence in Robert Browning’S “My Last Duchess”

Total Page:16

File Type:pdf, Size:1020Kb

Load more

Recommended publications

-

Classical Nakedness in British Sculpture and Historical Painting 1798-1840 Cora Hatshepsut Gilroy-Ware Ph.D Univ

MARMOREALITIES: CLASSICAL NAKEDNESS IN BRITISH SCULPTURE AND HISTORICAL PAINTING 1798-1840 CORA HATSHEPSUT GILROY-WARE PH.D UNIVERSITY OF YORK HISTORY OF ART SEPTEMBER 2013 ABSTRACT Exploring the fortunes of naked Graeco-Roman corporealities in British art achieved between 1798 and 1840, this study looks at the ideal body’s evolution from a site of ideological significance to a form designed consciously to evade political meaning. While the ways in which the incorporation of antiquity into the French Revolutionary project forged a new kind of investment in the classical world have been well-documented, the drastic effects of the Revolution in terms of this particular cultural formation have remained largely unexamined in the context of British sculpture and historical painting. By 1820, a reaction against ideal forms and their ubiquitous presence during the Revolutionary and Napoleonic wartime becomes commonplace in British cultural criticism. Taking shape in a series of chronological case-studies each centring on some of the nation’s most conspicuous artists during the period, this thesis navigates the causes and effects of this backlash, beginning with a state-funded marble monument to a fallen naval captain produced in 1798-1803 by the actively radical sculptor Thomas Banks. The next four chapters focus on distinct manifestations of classical nakedness by Benjamin West, Benjamin Robert Haydon, Thomas Stothard together with Richard Westall, and Henry Howard together with John Gibson and Richard James Wyatt, mapping what I identify as -

British Taste in the Nineteenth Century ••

BRITISH TASTE IN THE NINETEENTH CENTURY •• WILLIAM MULREADY The Sailing Match (S l) BRITISH TASTE IN THE NINETEENTH CENTURY AUCKLAND CITY ART GALLERY • MAY 1962 Foreword This exhibition has been arranged for the 1962 Auckland Festival of Arts. We are particularlv grateful to all the owners of pictures who have been so generous with their loans. p. A. TOMORY Director Introduction This exhibition sets out to indicate the general taste of the nineteenth century in Britain. As only New Zealand collections have been used there are certain inevitable gaps, but the main aim, to choose paintings which would reflect both the public and private patronage of the time, has been reasonably accomplished. The period covered is from 1820 to 1880 and although each decade may not be represented it is possible to recognise the effect on the one hand of increasing middle class patronage and on the other the various attempts like the Pre-Raphaelite move ment to halt the decline to sentimental triviality. The period is virtually a history of the Royal Academy, which until 1824, when the National Gallery was opened, provided one of the few public exhibitions of paintings. Its influence, therefore, even late in the century, on the public taste was considerable, and artistic success could onlv be assured by the Academy. It was, however, the rise of the middle class which dictated, more and more as the century progressed, the type of art produced by the artists. Middle class connoisseur- ship was directed almost entirely towards contemporary painting from which it de manded no more than anecdote, moral, sentimental or humorous, and landscapes or seascapes which proclaimed ' forever England.' Ruskin, somewhat apologetically (On the Present State of Modern Art 1867), detected two major characteristics — Compassionateness — which he observed had the tendency of '. -

William Etty Ra (1787-1849)

St Olave’s Churchyard WILLIAM ETTY RA (1787-1849) A BRIEF HISTORY RQHeM 3V315zyQ at Google Art Culture: Wikimedia Google 3V315zyQ at Art Culture: RQHeM William Etty – Self Portrait 1823 Written and researched by Helen Fields St Olave’s Church, York Helen Fields: 2019 Website: www.stolaveschurch.org.uk (Source: Bryan’s Dictionary of painters and engravers engravers and Dictionary painters of Bryan’s (Source: William Etty 2 Early life William Etty RA was born in 1787, during the reign of George III in Feasegate, York. He was the seventh child of Matthew and Esther Etty. Matthew owned a bakery and confectionery shop in Feasegate. The Ettys lived above the premises. Esther’s family had disapproved of her marriage to Matthew and disowned her, prompting the couple’s move from Pocklington to York, where they established their business and raised their family. They were staunch Methodists. William had three older surviving brothers, Walter, born in 1774, John, born in 1775, Thomas, born in 1780, and one younger brother Charles, born in 1793. The family seems to have been loving and caring and both parents encouraged their sons to aspire to successful careers. As an infant, William contracted smallpox and bore the scars of this throughout his life. His early schooling included attending a ‘dame-school’ in Feasegate and a school behind Goodramgate. Later, he became a weekly boarder at an academy in Pocklington. Although basic, Matthew and Esther considered the schooling of their sons important, despite the drain on family finances and during a time when the children of less affluent families were rarely educated. -

Art, Anatomy and the Modern Male Body by Anthea Callen

Roberto C. Ferrari book review of Looking at Men: Art, Anatomy and the Modern Male Body by Anthea Callen Nineteenth-Century Art Worldwide 18, no. 2 (Autumn 2019) Citation: Roberto C. Ferrari, book review of “Looking at Men: Art, Anatomy and the Modern Male Body by Anthea Callen,” Nineteenth-Century Art Worldwide 18, no. 2 (Autumn 2019), https://doi.org/10.29411/ncaw.2019.18.2.10. Published by: Association of Historians of Nineteenth-Century Art Notes: This PDF is provided for reference purposes only and may not contain all the functionality or features of the original, online publication. License: This work is licensed under a Creative Commons Attribution-NonCommercial 4.0 International License Creative Commons License. Ferrari: Looking at Men: Art, Anatomy and the Modern Male Body by Anthea Callen Nineteenth-Century Art Worldwide 18, no. 2 (Autumn 2019) Anthea Callen, Looking at Men: Art, Anatomy and the Modern Male Body. New Haven and London: Yale University Press, 2018. 272 pp.; 212 b&w and color illus.; bibliography; index. $60.00 (hardcover) ISBN: 978-0-300-11294-8 Every art historian who specializes in the long nineteenth century has engaged at one point or another with the male nude in art, from the beau idéal figures of Jacques-Louis David’s history paintings to the abstracted bodies among Paul Cézanne’s bathers. Nevertheless, representation of the male nude in mainstream art, film, and social media remains controversial, its taboo nature often generating responses ranging from excitement to disgust to embarrassment. The male nude certainly has received less critical attention in art history than the female nude, which has been displayed, appreciated, and critiqued extensively, and analyzed with methods ranging from formalism to feminism. -

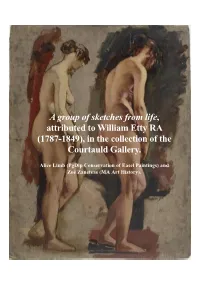

A Group of Sketches from Life, Attributed to William Etty RA (1787-1849), in the Collection of the Courtauld Gallery

A group of sketches from life, attributed to William Etty RA (1787-1849), in the collection of the Courtauld Gallery. Alice Limb (PgDip Conservation of Easel Paintings) and Zoë Zaneteas (MA Art History). Zoë Zaneteas and Alice Limb Painting Pairs 2019 A group of sketches from life, attributed to William Etty RA (1787-1849), in the collection of the Courtauld Gallery. This report was produced as part of the Painting Pairs project and is a collaboration between Zoë Zaneteas (MA Art History) and Alice Limb (PgDip Conservation of Easel Paintings).1 Aims of the Project This project focusses on a group of seven sketches on board, three of which are double sided, which form part of the Courtauld Gallery collection. We began this project with three overarching aims: firstly, to contextualize the attributed artist, William Etty, within the artistic, moral and social circumstances of his time and revisit existing scholarship; secondly, to examine the works from a technical and stylistic perspective in order to establish if their attribution is justified and, if not, whether an alternative attribution might be proposed; finally, to treat one of the works (CIA2583), including decisions on whether the retention of material relating to the work’s early physical history was justified and if this material further informs our knowledge of Etty’s practice. It must be noted that Etty was a prolific artist during the forty years he was active, and that a vast amount of artistic and archival material (both critical and personal) relates to him. This study will 1 Special thanks must go to: the staff of the Courtauld Gallery (especially Dr Karen Serres, Kate Edmondson and Graeme Barraclough), the staff of the Department of Conservation and Technology (especially Clare Richardson, Dr Pia Gotschaller and Professor Aviva Burnstock), Dr Beatrice Bertram of York City Art Gallery, Jevon Thistlewood and Morwenna Blewett of the Ashmolean Museum, and the staff of the Royal Academy Library, Archives and Stores (especially Helen Valentine, Annette Wickham, Mark Pomeroy, and Daniel Bowman). -

Nineteenth Century European Paintings, Drawings and Sculpture

NINETEENTH CENTURY EUROPEAN PAINTINGS, DRAWINGS AND SCULPTURE SUMMER EXHIBITION April 20th through June 26th, 2004 Exhibition organized by Robert Kashey and David Wojciechowski Catalogue by Elisabeth Kashey SHEPHERD & DEROM GALLERIES 58 East 79th Street New York, N. Y. 10021 Tel: 1 212 861 4050 Fax: 1 212 772 1314 e-mail: [email protected] © Copyright: Robert J. F. Kashey for Shepherd Gallery, Associates, 2004 COVER ILLUSTRATION: Henri Decaisne, Self-Portrait , 1820, cat. no. 2. GRAPHIC DESIGN: Keith Stout. PHOTOGRAPHY: Hisao Oka. TECHNICAL NOTES: All measurements are in inches and centimeters; height precedes width. All drawings and paintings are framed. Prices and photographs on request. All works subject to prior sale. SHEPHERD GALLERY SERVICES has framed, matted and restored all of the objects in this exhibi- tion which required it. The Service Department is open to the public by appointment, Tuesday through Saturday from 10:00 a.m. to 6:00 p.m. Tel: (212) 744 3392; fax: (212) 744 1525. CATALOGUE 1 THOMIRE, Pierre-Philippe 1751 - 1843 French School Rome (Vienna, Schatz- kammer; Paris, Louvre). CHARIOT, HORSES, AND SIX MALE Thomire’s involvement with porcelain manu- FIGURES, circa 1808 facturers (Sèvres), clock makers and furniture makers leaves a wide field to search for the pur- Wax relief on slate. Squared in graphite on slate. 13 pose of the present wax model. The processional 5/8” x 23 3/4” (34.6 x 60.3 cm). Signed in the wax at line-up and the treatment of the horses echo a lower right: THOMIRE. On verso various fragments of set of bronze mounts Thomire made in 1808 for print on paper; preserved from old backing a Sothe- two consoles, designed by Jacob-Desmalter for by’s label, illegible; also a printed label: J. -

William Etty’S Life William Etty Was Born in York

York Art Gallery Arts Heroes & Heroines William Etty’s life William Etty was born in York. When he was 12 he went to work for a printer in Hull. At 18 he moved to London to study art at the Royal Academy. William worked hard and was determined to become an artist. The artists at the Royal Academy were very impressed by his use of colour, especially the way he painted flesh tones, but it was many years before he began to sell his work regularly. William was in his 30s when he began to achieve some success. Although many people praised his talent, others did not like the fact that he often included nude people in his pictures. Soon the newspapers began to print both sides of the argument and William Etty became well known. But he still didn’t sell much of his work. He sometimes painted portraits, which helped him to earn more money. William What makes William Etty special? The Royal Academy of Art is run by artists, known as the Royal Academicians. There were 40 Royal Academicians, and when one of them retired or died those remaining would elect a new member. Etty In 1828 William Etty became a Royal Academician having won more votes than John Constable. In the 1840s, William turned to painting still life and landscapes. Painter He finally sold enough work to pay off his debts. Born: 10 March 1787 William Etty worked hard all his life to perfect his art. He carried on going to life drawing classes at the Royal Academy even after he was Died: 13 November 1849 made a Royal Academician and people though he shouldn’t. -

Press Release

PRESS Press Contact Rachel Eggers Manager of Public Relations [email protected] RELEASE 206.654.3151 APRIL 16, 2019 VICTORIAN RADICALS: FROM THE PRE-RAPHAELITES TO THE ARTS & CRAFTS MOVEMENT OPENS AT SEATTLE ART MUSEUM JUNE 13, 2019 Wide-ranging exhibition reveals how three generations of artists revolutionized the visual and decorative arts in Britain SEATTLE, WA – The Seattle Art Museum presents Victorian Radicals: From the Pre-Raphaelites to the Arts & Crafts Movement (June 13–September 8, 2019), exploring how three generations of rebellious British artists, designers, and makers responded to a time of great social upheaval and an increasingly industrial world. Organized by the American Federation of Arts and the Birmingham Museums Trust, the exhibition features 150 works from the collection of the city of Birmingham—many of which have never been shown outside of the United Kingdom—including paintings, drawings, books, sculptures, textiles, stained glass, and other decorative arts. They reveal a passionate artistic and social vision that revolutionized the visual arts in Britain. Victorian Radicals features work by notable Pre-Raphaelite and Arts & Crafts artists including Ford Madox Brown, Edward Burne-Jones, William Holman Hunt, John Everett Millais, William Morris, and Dante Gabriel Rossetti. Playing out against the backdrop of late 19th-century England, these influential movements were concerned with the relationship between art and nature, questions of class and gender, the value of the handmade versus machine production, and the search for beauty in an age of industry—all relevant issues in our current era of anxiety amid rapidly evolving technologies. “This exhibition is perfect for Seattle right now,” says Chiyo Ishikawa, SAM’s Susan Brotman Deputy Director for Art and Curator of European Painting and Sculpture. -

E-Bulletin No. 4 December 2020

e-Bulletin no. 4 December 2020 Contents EDITORIAL .................................................................................................................................. 2 INTRODUCING THE MA SCHOLAR FOR 2020, GRACE ENGLAND ............................................... 3 A NEWLY APPOINTED COMMITTEE MEMBER INTRODUCES HERSELF ...................................... 6 JOHN FLAXMAN (1755-1826) ..................................................................................................... 8 JACK HELLEWELL - ‘A FANATICAL PAINTER’ ............................................................................. 11 CANDAULES by WILLIAM ETTY ................................................................................................. 15 1 EDITORIAL So that’s 2020 nearly done with, and we find ourselves facing an uncertain 2021, with much depending on the availability of those vaccines on which we are counting for our return, probably a slow one and not without its difficulties, to something recognisable as normality. At least York’s return to Tier 2 means that we will be able to visit the Gallery again, albeit subject to restrictions and regulations adopted in response to the pandemic. But leaving the future aside, for the present I am delighted to bring together the fourth of the Friends of York Art Gallery e-Bulletins. Once again, I am grateful to contributors for providing an interesting mix of items. First, two new members of the Friends’ community introduce themselves: Grace England, who is the incoming Friends-supported -

William Etty the Artist

William Etty the artist William Etty was born in York in 1787. At his father’s request, he served several years as an apprentice to a printer in Hull. His uncle then invited him to stay in London where he was able to pursue his interest in painting at the Royal Academy School. As both a student and as a member of the academy he continued to study life classes there. He loved to paint the figure both clothed and nude. He eventually retired to York before he died in 1848. Statue of William Etty outside York Art Gallery. the work The Choice of Paris , also known as the Judgement of Paris, is a story from Greek mythology and was one of the events that led up to the Trojan War. This classical composition depicts three female nudes in the centre of the painting. The female on the left, Aphrodite (Goddess of Love) extends her hand to take the golden apple from Paris, son of Priam (King of Troy) which would pronounce her the fairest of all Gods. In exchange for the apple, Aphrodite would give him the most beautiful woman in the world, who was at this time Helen (of Sparta). And so the Trojan War started . Athena (far right) had promised Paris that he would be the most powerful King. Hera (centre) had promised to make him wise, even above some of the Gods. The two children near Athena’s legs are putti (cherubs), and the man behind Paris is Hermes, who delivered the apple to Paris from Zeus. -

Drawing After the Antique at the British Museum

Drawing after the Antique at the British Museum Supplementary Materials: Biographies of Students Admitted to Draw in the Townley Gallery, British Museum, with Facsimiles of the Gallery Register Pages (1809 – 1817) Essay by Martin Myrone Contents Facsimile TranscriptionBOE#JPHSBQIJFT • Page 1 • Page 2 • Page 3 • Page 4 • Page 5 • Page 6 • Page 7 Sources and Abbreviations • Manuscript Sources • Abbreviations for Online Resources • Further Online Resources • Abbreviations for Printed Sources • Further Printed Sources 1 of 120 Jan. 14 Mr Ralph Irvine, no.8 Gt. Howland St. [recommended by] Mr Planta/ 6 months This is probably intended for the Scottish landscape painter Hugh Irvine (1782– 1829), who exhibited from 8 Howland Street in 1809. “This young gentleman, at an early period of life, manifested a strong inclination for the study of art, and for several years his application has been unremitting. For some time he was a pupil of Mr Reinagle of London, whose merit as an artist is well known; and he has long been a close student in landscape afer Nature” (Thom, History of Aberdeen, 1: 198). He was the third son of Alexander Irvine, 18th laird of Drum, Aberdeenshire (1754–1844), and his wife Jean (Forbes; d.1786). His uncle was the artist and art dealer James Irvine (1757–1831). Alexander Irvine had four sons and a daughter; Alexander (b.1777), Charles (b.1780), Hugh, Francis, and daughter Christian. There is no record of a Ralph Irvine among the Irvines of Drum (Wimberley, Short Account), nor was there a Royal Academy student or exhibiting or listed artist of this name, so this was surely a clerical error or misunderstanding. -

BACON CHARDIN DEGAS LUCAS NAUMAN RODIN RUBENS York Art Gallery York Art Gallery

Exhibitions and Events September 2016 – March 2017 FLESH OPENS 23 SEPTEMBER A major exhibition featuring: BACON CHARDIN DEGAS LUCAS NAUMAN RODIN RUBENS York Art Gallery York Art Gallery Flesh 23 September 2016 – 19 March 2017 Human and animal, alive and dead, familiar and strange; this major exhibition will explore how artists represent flesh in their work. Works by Peter Paul Rubens, Edgar Degas, Jean- Baptiste Siméon Chardin, Francis Bacon, Circle of Rembrandt and Auguste Rodin, will show how the Circle of Rembrandt, The Carcase of an Ox, 1640-1645 Portrait of Henrietta Moraes on a Blue Couch, 1965 (oil on canvas), © CSG CIC Glasgow Museums Collection. Bacon, Francis (1909-92) / Manchester Art Gallery, UK / Bridgeman Images. body and flesh have long been subject to intense © The Estate of Francis Bacon. All rights reserved. DACS 2016. scrutiny by artists. These will be contrasted with contemporary works by internationally acclaimed artists Bruce Nauman, Jenny Saville, Adriana Varejeo and Berlinde de Bruyckere as well as pieces by Sarah Lucas, John Coplans and John Stezaker recently acquired by York Art Gallery through the Art Fund’s RENEW scheme. The exhibition will raise questions about the body and ageing, race and gender, touch and texture and surface and skin. Flesh is a partnership exhibition with the University of York, curated in collaboration with Dr Jo Applin (University of York/Courtald Institute of Art). Harold Gilman, Interior with Nude, 1911-12. Jen Davis, Untitled No 26., 2007. Courtesy of Lee Marks Fine Art, IN and ClampArt, NY 2 3 York Art Gallery York Art Gallery CoCA is located in two stunning first floor galleries framed by original architectural features and flooded with natural light.