You Think You Do, but You Don't: an Investigation of Fandom And

Total Page:16

File Type:pdf, Size:1020Kb

Load more

Recommended publications

-

Uila Supported Apps

Uila Supported Applications and Protocols updated Oct 2020 Application/Protocol Name Full Description 01net.com 01net website, a French high-tech news site. 050 plus is a Japanese embedded smartphone application dedicated to 050 plus audio-conferencing. 0zz0.com 0zz0 is an online solution to store, send and share files 10050.net China Railcom group web portal. This protocol plug-in classifies the http traffic to the host 10086.cn. It also 10086.cn classifies the ssl traffic to the Common Name 10086.cn. 104.com Web site dedicated to job research. 1111.com.tw Website dedicated to job research in Taiwan. 114la.com Chinese web portal operated by YLMF Computer Technology Co. Chinese cloud storing system of the 115 website. It is operated by YLMF 115.com Computer Technology Co. 118114.cn Chinese booking and reservation portal. 11st.co.kr Korean shopping website 11st. It is operated by SK Planet Co. 1337x.org Bittorrent tracker search engine 139mail 139mail is a chinese webmail powered by China Mobile. 15min.lt Lithuanian news portal Chinese web portal 163. It is operated by NetEase, a company which 163.com pioneered the development of Internet in China. 17173.com Website distributing Chinese games. 17u.com Chinese online travel booking website. 20 minutes is a free, daily newspaper available in France, Spain and 20minutes Switzerland. This plugin classifies websites. 24h.com.vn Vietnamese news portal 24ora.com Aruban news portal 24sata.hr Croatian news portal 24SevenOffice 24SevenOffice is a web-based Enterprise resource planning (ERP) systems. 24ur.com Slovenian news portal 2ch.net Japanese adult videos web site 2Shared 2shared is an online space for sharing and storage. -

Arena Tournament Rules

Emma Witkowski - “Inside the Huddle”, PhD Dissertation, 2012. Arena Tournament rules BlizzCon 2010 Tournament Rules. All matches that take place in the Tournament shall take place in accordance with the World of Warcraft Arena Rules, which are available at http://www.worldofwarcraft.com/pvp/arena/index.xml. In the event of any conflict between these Official Rules and the World of Warcraft Arena Rules, these Official Rules shall prevail. "Cheating," as determined in Sponsor's sole discretion, and specifically including, without limitation, "win-trading," shall result in disqualification of the Arena Team and all of its Team Members. Third party user interfaces compatible with World of Warcraft, and which do not violate the World of Warcraft Terms of Use may be used during the Qualification Round of the Tournament, but will not be allowed at the Regional Qualifier or the Finals. At the Regional Finals, Team Members will have fifteen (15) minutes prior to the start of the first match with each opponent Team Member to prepare the computer on which they will use to participate in the Tournament match. Determination of Winners Qualification Rounds and Regional Qualifier Tournaments The Qualification Round of the Tournament . The Qualification Round of the Tournament shall last for approximately eight weeks, and will commence on April 27, 2010 at approximately 10:00 AM Pacific Time (5:00 PM GMT) (subject to ‘Server Maintenance’ to be performed by Sponsor), and end on June 21, 2010 at approximately 9:00 PM Pacific Time (4:00 AM GMT). The first four weeks of the Qualification Round will be a “practice” period, and during this time Eligible Participants may switch from one team to another without that Arena Team being penalized. -

620-100531B E3 Emerge UL Installation Instructions.Indd

PRINTER’S INSTRUCTIONS: e3 eMerge Access Control System Document Number: 620-100531, Rev. B Installation Instructions SIZE: FLAT 17.000” X 11.000”, FOLDED 8.500” X 11.000” - FOLDING: ALBUM FOLD - BINDING: SADDLE STITCH - SCALE: 1-1 SADDLE STITCH - SCALE: FOLD - BINDING: ALBUM - FOLDING: X 11.000” X 11.000”, FOLDED 8.500” 17.000” FLAT SIZE: MANUAL,INSTALLATION,E3 EMERGE,UL - P/N: 620-100531 B - INK: BLACK - MATERIAL: GUTS 80G WOOD FREE, COVER 157G COATED GLOSS ART 157G COATED FREE, COVER WOOD GUTS 80G - MATERIAL: BLACK 620-100531 B - INK: EMERGE,UL - P/N: MANUAL,INSTALLATION,E3 Notices All rights strictly reserved. No part of this document may be reproduced, copied, adapted, or transmitted in any form or by any means without written permission from Nortek Security & Control LLC. Standards Approvals This equipment has been tested and found to comply with the limits for a Class A digital device, pursuant to part 15 of the FCC Rules. These limits are designed to provide reasonable protection against harmful interference when the equipment is operated in a commercial environment. This equipment generates, uses, and can radiate radio frequency energy and, if not installed and used in accordance with the instruction manual, may cause harmful interference to radio communications. Operation of this equipment a residential area is likely to cause harmful interference in which case the user will be required to correct the interference at his own expense. e3 eMerge systems are Level I UL 294 listed devices and must be installed in controlled locations. Corporate Office Nortek Security & Control LLC 1950 Camino Vida Roble, Suite 150 Carlsbad, CA 92008-6517 Tel: (800) 421-1587 / 760-438-7000 Fax: (800) 468-1340 / 760-931-1340 Technical Support Tel: (800) 421-1587 Hours: 5:00 AM to 4:30 PM Pacific Time, Monday - Friday Notice It is important that this instruction manual be read and understood completely before installation or operation is attempted. -

UTOPIA Still Alive in Centerville Graduation by JENNIFFER WARDELL Services on a Residential Basis

Celebrating 125 years as Davis County’s news source Immigrants, refugees graduate The from ESL program Davis Clipper ON A6 75 cents VOL. 125 NO. 44 THURSDAY, JUNE 8, 2017 UTOPIA still alive in Centerville Graduation BY JENNIFFER WARDELL services on a residential basis. The increase fast enough to keep the city’s financial section [email protected] in that number has been higher the past year commitments to UTOPIA from increasing. than it has been in any years previous, and The city first agreed to the commitments Find the names of between residential and business customers back in the early 2000s, when they joined in graduates from all there are now 1,563 UTOPIA customers in the on the plan to bring high-speed Internet to CENTERVILLE—Despite the city. smaller cities, and an increase in 2008. Those district schools in city council saying “no” to in- “High speed Internet seems to be in higher commitments have increased 2 percent every Davis County. demand than it was four or five years ago,” year since, and in the upcoming fiscal year will creased fees from UTOPIA in said Cutler, who is also a member of the be $472,212. 2014, the fiber-optic network still UIA board of cities associated with UTOPIA. “Could that money be used for other things? GRADUATION, E1 “UTOPIA financial situation is continuing to Sure,” said Centerville City Manager Steve has a presence in Centerville. slowly improve. We’d like it to improve rapidly, Thacker. “But we plan ahead.” According to Centerville Mayor Paul Cutler, but we’ll take slower improvements.” one-third of residents are now taking UTOPIA That improvement, however, isn’t coming n See “UTOPIA” p. -

There Are No Women and They All Play Mercy

"There Are No Women and They All Play Mercy": Understanding and Explaining (the Lack of) Women’s Presence in Esports and Competitive Gaming Maria Ruotsalainen University of Jyväskylä Department of Music, Art and Culture Studies Pl 35, 40014 University of Jyväskylä, Finland +358406469488 [email protected] Usva Friman University of Turku Digital Culture P.O.Box 124 FI-28101 Pori, Finland [email protected] ABSTRACT In this paper, we explore women’s participation in esports and competitive gaming. We will analyze two different types of research material: online questionnaire responses by women explaining their reluctance to participate in esports, and online forum discussions regarding women’s participation in competitive Overwatch. We will examine the ways in which women’s participation – its conditions, limits and possibilities – are constructed in the discussions concerning women gamers, how women are negotiating their participation in their own words, and in what ways gender may affect these processes. Our findings support those made in previous studies concerning esports and competitive gaming as fields dominated by toxic meritocracy and hegemonic (geek) masculinity, and based on our analysis, women’s room for participation in competitive gaming is still extremely limited, both in terms of presence and ways of participation. Keywords Gender, esports, hegemonic geek masculinity, toxic meritocracy, Overwatch INTRODUCTION "Why do the female humans always play the female characters?" Acayri wondered soon thereafter. "Like, they're always playing Mercy." "They can't play games and be good at them —" Joel responded. "That's true, so they just pick the hottest girl characters," Acayri said. The previous is an excerpt of an article published on a digital media site Mic on May 11th 2017 (Mulkerin, 2017). -

Q. Where Can I Purchase the Blizzcon 2019 War Chest? A

[FOR VIEWERS] Q. How can I begin earning War Chest XP on Twitch? A. To begin earning War Chest XP on Twitch, please complete the following steps: Step 1: Link your Blizzard account to your Twitch account. Step 2: Head over to Twitch, log in to your linked account, and check out who’s streaming StarCraft II. Step 3: Find any StarCraft II stream that’s enabled the War Chest extension. Step 4: Grant the War Chest extension access to your Twitch ID and watch for at least 20 minutes. Step 5: When it appears, click the “Claim XP” button in the extension to redeem your reward. Step 6: Log in to StarCraft II to add the XP reward to your War Chest. Upgrade your War Chest with the Terran, Protoss, Zerg, or Complete Bundle passes to instantly apply any XP you've earned toward even more rewards and help support StarCraft esports! Check out our official blog post for additional information on the BlizzCon 2019 War Chest. (If you have never played StarCraft II, you will need to log in to the game at least once before you can earn War Chest XP rewards on Twitch. Click here to get started.) Q. Where can I purchase the BlizzCon 2019 War Chest? A. You can purchase a BlizzCon 2019 War Chest for the race of your choice for $9.99 each or buy the complete bundle for $24.99 on the Blizzard Shop. This War Chest offer is only available for a limited time, though! Be sure to buy yours before November 7, 2019. -

Southern Fandom Confederation Bulletin

Southern Fandom Confederation Bulletin Volume 6, No. 6: October, 1996 Southern Fandom Confederation Contents Ad Rates The Carpetbagger..................................................................... 1 Type Full-Page Half-Page 1/4 Page Another Con Report................................................................4 Fan $25.00 $12.50 $7.25 Treasurer's Report................................................................... 5 Mad Dog's Southern Convention Listing............................. 6 Pro $50.00 $25.00 $12.50 Southern Fanzines................................................................... 8 Southern Fandom on the Web................................................9 Addresses Southern Clubs...................................................................... 10 Letters..................................................................................... 13 Physical Mail: SFC/DSC By-laws...................................................... 20 President Tom Feller, Box 13626,Jackson, MS 39236-3626 Cover Artist........................................................John Martello Vice-President Bill Francis, P.O. Box 1271, Policies Brunswick, GA 31521 The Southern Fandom Confederation Bulletin Secretary-Treasurer Judy Bemis, 1405 (SFCB) Vol. 6, No. 6, October, 1996, is the official Waterwinds CT,Wake Forest, NC 27587 publication of the Southern Fandom Confederation (SFC), a not-for-profit literary organization and J. R. Madden, 7515 Shermgham Avenue, Baton information clearinghouse dedicated to the service of Rouge, LA 70808-5762 -

Using the ZMET Method to Understand Individual Meanings Created by Video Game Players Through the Player-Super Mario Avatar Relationship

Brigham Young University BYU ScholarsArchive Theses and Dissertations 2008-03-28 Using the ZMET Method to Understand Individual Meanings Created by Video Game Players Through the Player-Super Mario Avatar Relationship Bradley R. Clark Brigham Young University - Provo Follow this and additional works at: https://scholarsarchive.byu.edu/etd Part of the Communication Commons BYU ScholarsArchive Citation Clark, Bradley R., "Using the ZMET Method to Understand Individual Meanings Created by Video Game Players Through the Player-Super Mario Avatar Relationship" (2008). Theses and Dissertations. 1350. https://scholarsarchive.byu.edu/etd/1350 This Thesis is brought to you for free and open access by BYU ScholarsArchive. It has been accepted for inclusion in Theses and Dissertations by an authorized administrator of BYU ScholarsArchive. For more information, please contact [email protected], [email protected]. Using the ZMET Method 1 Running head: USING THE ZMET METHOD TO UNDERSTAND MEANINGS Using the ZMET Method to Understand Individual Meanings Created by Video Game Players Through the Player-Super Mario Avatar Relationship Bradley R Clark A project submitted to the faculty of Brigham Young University in partial fulfillment of the requirements for the degree of Master of Arts Department of Communications Brigham Young University April 2008 Using the ZMET Method 2 Copyright © 2008 Bradley R Clark All Rights Reserved Using the ZMET Method 3 Using the ZMET Method 4 BRIGHAM YOUNG UNIVERSITY GRADUATE COMMITTEE APPROVAL of a project submitted by Bradley R Clark This project has been read by each member of the following graduate committee and by majority vote has been found to be satisfactory. -

REGAIN CONTROL, in the SUPERNATURAL ACTION-ADVENTURE GAME from REMEDY ENTERTAINMENT and 505 GAMES, COMING in 2019 World Premiere

REGAIN CONTROL, IN THE SUPERNATURAL ACTION-ADVENTURE GAME FROM REMEDY ENTERTAINMENT AND 505 GAMES, COMING IN 2019 World Premiere Trailer for Remedy’s “Most Ambitious Game Yet” Revealed at Sony E3 Conference Showcases Complex Sandbox-Style World CALABASAS, Calif. – June 11, 2018 – Internationally renowned developer Remedy Entertainment, Plc., along with its publishing partner 505 Games, have unveiled their highly anticipated game, previously known only by its codename, “P7.” From the creators of Max Payne and Alan Wake comes Control, a third-person action-adventure game combining Remedy’s trademark gunplay with supernatural abilities. Revealed for the first time at the official Sony PlayStation E3 media briefing in the worldwide exclusive debut of the first trailer, Control is set in a unique and ever-changing world that juxtaposes our familiar reality with the strange and unexplainable. Welcome to the Federal Bureau of Control: https://youtu.be/8ZrV2n9oHb4 After a secretive agency in New York is invaded by an otherworldly threat, players will take on the role of Jesse Faden, the new Director struggling to regain Control. This sandbox-style, gameplay- driven experience built on the proprietary Northlight engine challenges players to master a combination of supernatural abilities, modifiable loadouts and reactive environments while fighting through the deep and mysterious worlds Remedy is known and loved for. “Control represents a new exciting chapter for us, it redefines what a Remedy game is. It shows off our unique ability to build compelling worlds while providing a new player-driven way to experience them,” said Mikael Kasurinen, game director of Control. “A key focus for Remedy has been to provide more agency through gameplay and allow our audience to experience the story of the world at their own pace” “From our first meetings with Remedy we’ve been inspired by the vision and scope of Control, and we are proud to help them bring this game to life and get it into the hands of players,” said Neil Ralley, president of 505 Games. -

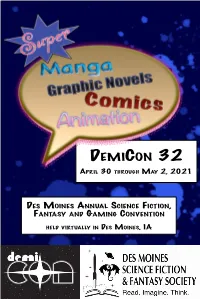

Demicon 32 Program Book

DEMICON 32 APRIL 30 THROUGH MAY 2, 2021 DES MOINES ANNUAL SCIENCE FICTION, FANTASY AND GAMING CONVENTION HELD VIRTUALLY IN DES MOINES, IA CONTENTS Welcome - 4 Department Heads/DMSFFS - 5 Virtual World of DemiCon - 6 Convention Rules - 8 Guests Guests of Honor/Toastmasters - 10 Professional Guests/ Memorial - 12 Hall of Fame - 14 Artwork - 15 Donate/Charity Auction - 16 Venues - 17 Shopping Venues - 18 Programming - 19 Areas of Interest Contests - 20 DemiCon Channel - 22 Gaming - 23 Programming Schedule - 24 Thank You - 27 The After: DemiCon 2022 - 28 CONCOM THE DES MOINES SCIENCE FICTION & “ALL OUR DREAMS CAN COME TRUE, IF WE HAVE THE COURAGE TO FANTASY SOCIETY,INC. (DMSFFS)IS THE CONCOM: JOE STRUSS,SALLIE ABBA,JESSICA GUILE, PURSUE THEM.” – WALT DISNEY LOCAL 501(C)(3) CHARITY NON-PROFIT JUDY ZAJEC,NATE FARMER ORGANIZATION THAT SPONSORS DEMICON. ANIMÉ: SAM SAM HACKETT YES, AND WELCOME TO DEMICON 32: SUPER MANGA GRAPHIC THIS VOLUNTEER RUN ORGANIZATION STANDS ARCHIVIST: SALLIE ABBA NOVELS COMICS ANIMATION! BY THE ORGANIZATIONʻS MISSION ART SHOW: MICHAEL OATMAN MAKE SURE YOU MEET OUR ARTIST GUESTS OF HONOR AND DRAGON SALLIE ABBA STATEMENT: TO INSPIRE INDIVIDUALS AND BLOOD DRIVE: SHERIL BOGENRIEF AFICIONADOS DAVID LEE PANCAKE AND ALISON JOHNSTUN.OUR COMMUNITIES TO READ,IMAGINE AND LORD OF DRINK: KRIS MCBRIDE AUTHOR GUEST OF HONOR IS THE INCREDIBLE LETTIE PRELL. HER WORK THINK; CREATING A BETTER WORLD CHANNEL MASTER: JOE STRUSS EXPLORES THE EDGE WHERE HUMANS AND THEIR TECHNOLOGY ARE THROUGH EDUCATION AND SUPPORT OF CONSUITE: MANDI ARTHUR-STRUSS,MONICA OATMAN, INCREASINGLY MERGING. LITERACY, SCIENCE, AND THE ARTS.DEMICON WIL WARNER SUSAN LEABHART AND MITCH THOMPSON ARE OUR WONDERFUL IS ONE OF MANY EVENTS THAT DMSFFS CONTESTS: SALLIE ABBA TOASTMASTERS.SUE IS OFTEN FOUND REGALING ON MANY DIVERSE AND HOSTS HE REST OF THE YEAR IS FILLED WITH .T DATABASE: CRAIG LEABHART INTERESTING TOPICS (LIKE TIME TRAVELING). -

March 2015 Discerning Solutions to the Challenges

Inside this issue 3 Scott and Kimberly Hahn to speak on marriage 14 Mother Dolores Hart to speak at CAPP breakfast Please visit us on: at www.facebook.com/ bridgeportdiocese at www.twitter.com/ dobevents, dobyouth Latest news: bridgeportdiocese.com Frank E. Metrusky, CFP® President and Financial Advisor 945 Beaver Dam Road Stratford, CT 06614 203.386.8977 Securities and Advisory Services offered through National Planning Corporation (NPC), Member FINRA/SIPC, and a Registered Investment Advisor. Catholic Way investments and NPC are separate and unrelated companies. 2 March 2015 www.2014synod.org Discerning solutions to the challenges... Dear Brothers and Sisters How do we evangelize and in Christ, form our parents to be able to share with their children their We are halfway through with relationship with Jesus and our diocesan synod! the Church? What needs to be At our February 7 session, done so that the diocese and our the synod delegates approved the parishes provide support and language of five global challenges pastoral care to families that are that will be established as prior- facing particular stressors such as ities for the coming years. As I financial difficulties, employment said to the delegates, these are issues, discrimination, immigra- not the only issues that will be tion challenges, addiction, or addressed in revitalizing our dio- marital breakup? cese, but will be our most imme- diate priorities. We know that 3. Evangelization—We must cre- there are many other challenges ate concrete plans for evangelization facing our youth, our families, in, with and through our parishes, and our communities throughout schools, ecclesial movements and com- Fairfield County. -

Download a Transcript of the Episode

Leora Kornfeld (00:09): Welcome to Now and Next. It's a podcast about innovation in the media and entertainment industries. I'm Leora Kornfeld. I think a lot of us have been asking ourselves what part of the pandemic are we now in? Yes, from a public health perspective, of course, but also from the learning to adapt to a new reality perspective. And this new reality means the world doesn't stop. It just moves in different ways. So on this episode, we're going to look at what some of those new ways are, specifically for the game industry, because it's an industry that historically has relied on big, I mean, really big industry events for meeting people, for exchanging new ideas and for seeing what the latest and greatest is. Leora Kornfeld (00:55): At events like GDC, the Game Developer's Conference, or E3. Every year, tens of thousands of game developers, publishers, and distributors, head to California and meet and greet each other, make deals, go for dinners, make more deals, then go to some parties, then meet more people. And then wake up and do it all over again the next day. Oh, and somewhere in there, they go to some conference events too, but not this year. Angela Mejia (01:23): It was a massive cancellation of physical events. Events are a big deal for the industry because that's really when developers get in contact with the players. And these events are like huge parties and people that go there is so much fun.