Felipe, Alexie Z.N. (2015) Small-Scale Mining on Mt. Balabag

Total Page:16

File Type:pdf, Size:1020Kb

Load more

Recommended publications

-

Emindanao Library an Annotated Bibliography (Preliminary Edition)

eMindanao Library An Annotated Bibliography (Preliminary Edition) Published online by Center for Philippine Studies University of Hawai’i at Mānoa Honolulu, Hawaii July 25, 2014 TABLE OF CONTENTS Preface iii I. Articles/Books 1 II. Bibliographies 236 III. Videos/Images 240 IV. Websites 242 V. Others (Interviews/biographies/dictionaries) 248 PREFACE This project is part of eMindanao Library, an electronic, digitized collection of materials being established by the Center for Philippine Studies, University of Hawai’i at Mānoa. At present, this annotated bibliography is a work in progress envisioned to be published online in full, with its own internal search mechanism. The list is drawn from web-based resources, mostly articles and a few books that are available or published on the internet. Some of them are born-digital with no known analog equivalent. Later, the bibliography will include printed materials such as books and journal articles, and other textual materials, images and audio-visual items. eMindanao will play host as a depository of such materials in digital form in a dedicated website. Please note that some resources listed here may have links that are “broken” at the time users search for them online. They may have been discontinued for some reason, hence are not accessible any longer. Materials are broadly categorized into the following: Articles/Books Bibliographies Videos/Images Websites, and Others (Interviews/ Biographies/ Dictionaries) Updated: July 25, 2014 Notes: This annotated bibliography has been originally published at http://www.hawaii.edu/cps/emindanao.html, and re-posted at http://www.emindanao.com. All Rights Reserved. For comments and feedbacks, write to: Center for Philippine Studies University of Hawai’i at Mānoa 1890 East-West Road, Moore 416 Honolulu, Hawaii 96822 Email: [email protected] Phone: (808) 956-6086 Fax: (808) 956-2682 Suggested format for citation of this resource: Center for Philippine Studies, University of Hawai’i at Mānoa. -

Higaunon & Subanen Cross Sharing, Learning Reflection & Integration

Higaunon & Subanen Cross sharing, Learning Reflection & Integration for Peace and Solidarity April 16-22,2017 Activity documentation Executive Summary Almost three years ago, this activity is originally entitled: On-site Inter-Ancestral Domain Council Cross-Sharing, Integration and Learning Reflection for 22 IP scholars. With long time gap between original design and date of implementation, revision was inevitable to fit into the current situation and ensuring the activity objectives were attained. Renaming the activity into Higaunon & Subanen Cross-sharing, Learning Reflection & Integration for Peace and Solidarity; reducing the number of days activity from 15 to seven-days and adding two budget line items were three necessary adjustments made that lead to a successful end. As the project will terminate on the 30th day of June 2017, one participant said, “it is a beautiful way to end the project”, as the activity is the last training-related activity before the Project Terminal Evaluation and Learning Workshop. The seven-day (April 16 to 22, 2017) cross-sharing activity covered the wide ranging learning exchanges such as: indigenous farming practices; actual trekking on tribal sacred places and fresh water lake; observing an Indigenous People’s Mandatory Representative (IPMR) Datu doing his policy legislation in City Council Session; listening to the sharing from the Community Relation Officer (ComRel) of large-scale mining company; interacting with the IP leaders who become squatters in their own land because of huge transnational Palm plantation; and a city officer, who is also a tribal leader that effectively handles the city’s IP affairs office. Places for exposures sites are predetermined based on the topics and themes it represent or to showcase. -

Proceeding 2018

PROCEEDING 2018 CO OCTOBER 13, 2018 SAT 8:00AM – 5:30PM QUEZON CITY EXPERIENCE, QUEZON MEMORIAL, Q.C. GRADUATE SCHOOL OF BUSINESS Tabassam Raza, MAURP, DBA, Ph.D. P.E. EDITOR-IN-CHIEF EDITOR Ernie M. Lopez, MBA Ramon Iñigo M. Espinosa, AA MANAGING EDITOR EDITORIAL BOARD Jose F. Peralta, DBA, CPA PRESIDENT, CHIEF ACADEMIC OFFICER & DEAN Antonio M. Magtalas, MBA, CPA VICE PRESIDENT FOR FINANCE & TREASURER Tabassam Raza, MAURP, DBA, Ph.D. P.E. ASSOCIATE DEAN Jose Teodorico V. Molina, LLM, DCI, CPA CHAIR, GSB AD HOC COMMITTEE EDITORIAL STAFF Ernie M. Lopez Susan S. Cruz Ramon Iñigo M. Espinosa Philip Angelo Pandan The PSBA THIRD INTERNATIONAL RESEARCH COLLOQUIUM PROCEEDINGS is an official business publication of the Graduate School of Business of the Philippine School of Business Administration – Manila. It is intended to keep the graduate students well-informed about the latest concepts and trends in business, management and general information with the goal of attaining relevance and academic excellence. PSBA Manila 3IRC Proceedings Volume III October 2018 TABLE OF CONTENTS Description Page Table of Contents ................................................................................................................................. i Concept Note ....................................................................................................................................... 2 Program of Activities .......................................................................................................................... 6 Resource -

Southern Philippines, February 2011

Confirms CORI country of origin research and information CORI Country Report Southern Philippines, February 2011 Commissioned by the United Nations High Commissioner for Refugees, Division of International Protection. Any views expressed in this paper are those of the author and are not necessarily those of UNHCR. Preface Country of Origin Information (COI) is required within Refugee Status Determination (RSD) to provide objective evidence on conditions in refugee producing countries to support decision making. Quality information about human rights, legal provisions, politics, culture, society, religion and healthcare in countries of origin is essential in establishing whether or not a person’s fear of persecution is well founded. CORI Country Reports are designed to aid decision making within RSD. They are not intended to be general reports on human rights conditions. They serve a specific purpose, collating legally relevant information on conditions in countries of origin, pertinent to the assessment of claims for asylum. Categories of COI included within this report are based on the most common issues arising from asylum applications made by nationals from the southern Philippines, specifically Mindanao, Tawi Tawi, Basilan and Sulu. This report covers events up to 28 February 2011. COI is a specific discipline distinct from academic, journalistic or policy writing, with its own conventions and protocols of professional standards as outlined in international guidance such as The Common EU Guidelines on Processing Country of Origin Information, 2008 and UNHCR, Country of Origin Information: Towards Enhanced International Cooperation, 2004. CORI provides information impartially and objectively, the inclusion of source material in this report does not equate to CORI agreeing with its content or reflect CORI’s position on conditions in a country. -

Co-Creating Peace in Conflict-Affected Areas in Mindanao.Pdf

Copyright © 2013 by The Asian Institute of Management Published by The AIM-TeaM Energy Center for Bridging Leadership of the AIM-Scientific Research Foundation, Inc. All rights reserved. This collation of narratives, speeches, documents is an open source document for all development practitioners within the condition that publisher is cited and notified in writing when material is used, reproduced, distributed, or transmitted in any form or by any means, including photocopying, recording, or other electronic or mechanical methods. Requests for permission should be directed to [email protected], or mailed to 3rd Level, Asian Institute of Management Joseph R. McMicking Campus, 123 Paseo de Roxas, MCPO Box 2095, 1260 Makati City, Philippines. ISBN No. Book cover photo: Three doves just released by a group of Sulu residents, taken on June 8, 2013 Photographed by: Lt. Col. Romulo Quemado CO-CREATING PEACE IN CONFLICT-AFFECTED MINDANAO A FELLOW AT A TIME VOLUME 1 AIM TeaM Energy Center for Bridging Leadership www.bridgingleadership.aim.edu Asian Institute of Management 123 Paseo de Roxas Street, Makati City 1226, Philippines Tel. No: +632 892.4011 to 26 Message Greetings! In behalf of the Asian Institute of Management, I am honored to present to everyone this publication, entitled “Co-Creating Peace in Mindanao (A Fellow at a Time),” a product of one of our most renowned leadership programs offered by the AIM Team Energy Center for Bridging Leadership. The Mindanao Bridging Leaders Program (MBLP) began in 2005 and is hinged on the Bridging Leadership Framework. The fellows- who graduated the program are executive officers and distinguished directors, representing different sectors from the government, non-gov ernment organizations, civil society organizations, security, and others. -

7011- Office of the Sangguniang Bayan Municipal

Republic of the Philippines Province of Zamboanga del Sur MUNICIPALITY OF BAYOG -7011- OFFICE OF THE SANGGUNIANG BAYAN MUNICIPAL ORDINANCE NO. 13-200-16 AN ORDINANCE DEFINING THE OFFICIAL SEAL OF THE MUNICIPALITY OF BAYOG, ZAMBOANGA DEL SUR. BE IT ORDAINED by the 13TH Sangguniang Bayan of Bayog, Zamboanga del Sur, on its 22ND Regular Session held at the Municipal Session Hall on December 15, 2016 at 9:00 o’clock in the morning. SECTION I. SCOPE: A seal is used to authenticate a corporate act which is usually done and brought into effect thru the execution of legal instruments manifesting corporate existence. The Municipality of Bayog has its own official seal bearing significant designs reflecting our rivers, forest and mining resources, including agricultural and timber lands. SECTION II. FOUR (4) MAJOR NATURAL RESOURCES REFLECTED IN THE OFFICIAL SEAL AS DEFINED: Rivers - The Municipality of Bayog is traversed by two (2) big bodies of rivers, in which the raging current during continuous rains swiftly dash out to the coastal areas of the neighboring province of Zamboanga Sibugay. At the eastern part, Sibuguey River in a snake-like form that originates from the distant Barangay Sigacad has a total length of 43,398 meters and find its exit down to the boundary of the adjacent Municipality of Diplahan, Zamboanga Sibugay. With resembling notoriety, Dipili River in the west is much shorter having a length only of 18,724 meters since it joins Sibuguey River at the outskirt of Barangay Salawagan. There are four (4) other smaller rivers traversing the hinterland and lowland areas namely: Depore River with a length of 10,065 meters, Depase River with a length of 8,091 meters, Bobuan River with 20,232 meters and Malubog River the shortest having a length only of 1,772 meters. -

Bayog Bags SGLG Twice in a Row

VOLUME I, ISSUE 1 MAY - DECEMBER 2017 Bayog bags SGLG twice in a row The Local Government of Bayog under the management of Mayor Leonardo L. Babasa, Jr. received the Seal of Good Local Governance from the Department of the Interior and Local Government (DILG) for the second time last November 29, 2017 at Manila Hotel, Tent City, Manila. Bayog is among the 448 LGUs all over the country, 28 are provinces, 60 are cities, and 359 are municipalities who have proven their worth to grab the 2017 Seal of Good Local Governance. Other municipalities in Region IX who also received the SGLG were Labason, Manukan, Piñan, and Siocon from Zamboanga del Norte; Imelda, Siay, and Tungawan from Zamboanga Sibugay; and Bayog, Dumalinao, Mahayag, Molave, Ramon Magsaysay, San Pablo, and Vincenzo Sagun from Zamboanga del Sur. “Hopefully, we will be a Hall of Famer next year if everybody will continue to do their part in this LGU,” Mayor Left to Right: Mario A. Baterna, LGOO VI-DILG, Mayor Leonardo L. Babasa‟s statement when he presented the seal to the LGU Babasa, Jr., Vice Mayor Celso A. Matias, together with Arnel F. officials and rank-and-file employees. Gudio , Provincial Director of DILG Zamboanga del Sur. Bayog holds Leadership Summit The Local Government Unit of Bayog in Development and Interpersonal cooperation with the 44IB, Philippine Army held Communication. a Youth Leadership Summit on October 18-21, On the other hand, the 2017 at the Municipal Gymnasium, this participants were grouped to Municipality with the theme “Strengthening compete for various contests Agriculture thru Organic Farming towards like Literary and Musical Con- ASEAN Development”. -

One Big File

MISSING TARGETS An alternative MDG midterm report NOVEMBER 2007 Missing Targets: An Alternative MDG Midterm Report Social Watch Philippines 2007 Report Copyright 2007 ISSN: 1656-9490 2007 Report Team Isagani R. Serrano, Editor Rene R. Raya, Co-editor Janet R. Carandang, Coordinator Maria Luz R. Anigan, Research Associate Nadja B. Ginete, Research Assistant Rebecca S. Gaddi, Gender Specialist Paul Escober, Data Analyst Joann M. Divinagracia, Data Analyst Lourdes Fernandez, Copy Editor Nanie Gonzales, Lay-out Artist Benjo Laygo, Cover Design Contributors Isagani R. Serrano Ma. Victoria R. Raquiza Rene R. Raya Merci L. Fabros Jonathan D. Ronquillo Rachel O. Morala Jessica Dator-Bercilla Victoria Tauli Corpuz Eduardo Gonzalez Shubert L. Ciencia Magdalena C. Monge Dante O. Bismonte Emilio Paz Roy Layoza Gay D. Defiesta Joseph Gloria This book was made possible with full support of Oxfam Novib. Printed in the Philippines CO N T EN T S Key to Acronyms .............................................................................................................................................................................................................................................................................. iv Foreword.................................................................................................................................................................................................................................................................................................... vii The MDGs and Social Watch -

US Envoy Visits MILF Camp

Vol. 3 No. 3 March 2008 Peace Monitor US envoy visits MILF camp SULTAN KUDARAT, Shariff Kabunsuan (Wednesday, February 20, 2008)– US Ambassador Kristie Kenney yesterday visited the Moro Islamic Liberation Front (MILF) stronghold in an attempt to re- open stalled peace talks between the government and the rebels’ group. Kenney huddled briefly with key members of the MILF central committee, but told reporters that her coming to Camp Darapanan, now the MILF’s central headquarters, was a “private visit.” She was greeted by MILF fighters in combat uniform and armed with M-16 rifles and rocket-propelled grenades. She met with MILF chief Muhammad Murad behind closed doors for about an hour before leaving. Kenney, who has toured Central Mindanao the past [US /p.11] HISTORIC --- US Ambassador Kristie Kenney and MILF Chairman Al-Haj Murad emerge from the MILF’s liaison center after after a brief meeting during the envoy’s visit Ceasefire violations almost to Darapanan, Sultan Kudarat town in Shariff Kabunsuan zero, says Malaysian general last February 19. [] ZAMBOANGA CITY (Friday, February 8, 2008 )– Walkout threat mars Almost nil. Istanbul talks Thus said Malaysian Maj. Gen. Datuk Mat Yasin bin Inclusion of ARMM Organic Act becomes Daud, head of the International Monitoring Team (IMT), of ceasefire violations by either the military or the Moro thorny issue in talks Islamic Liberation Front (MILF). The government of the Republic of the Philippines Skirmishes that could threaten the ceasefire between (GRP) and the Moro National Liberation Front (MNLF), the two “have gone down very drastically,” said Daud, which have been at odds over the implementation of the who heads the fourth batch of the Malaysian-led IMT. -

Bayog Pcr.Pdf

EXECUTIVE SUMMARY The Community-Based Forest Management Program (CBFMP) revolutionized forest development and rehabilitation efforts of the government when it was institutionalized in 1995 by virtue of Executive Order No. 263. Before the adoption of the CBFM approach, the sole motivating factor of contract reforestation awardees was primarily financial gains. With the implementation of the Forestry Sector Project (FSP) using CBFM as its main strategy to rehabilitate the upland ecosystem, it empowered beneficiary communities economically, socially, technically and politically while transforming them into environmentally responsible managers. The tenurial right to develop subproject sites alongside the various inputs from the Subproject deepened their commitment to collaborate with other stakeholders in the implementation of these subprojects. The Bayog Watershed Rehabilitation Subproject is in Zamboanga del Sur and covers 11 barangays within the Municipality of Bayog. Sibugay River which is responsible for irrigating farmlands of Sibugay Province and Zamboanga del Sur is also within the Subproject site. The implementation of the Comprehensive Site Development (CSD) activities stands out among other components as it manifests the People’s Organization’s zeal and commitment to go beyond targets and work for the success of the Project. From the original target of 2,020 hectares, the Bayog Watershed Rehabilitation Subproject Association, Inc. (BAWARSA, Inc.) was able to develop a total area of 2,164.09 hectares or an excess of 144.09 hectares without the benefit of any additional budget for nursery and plantation establishment. For this achievement, an expansion area was granted to BAWARSA Inc. covering an additional six barangays with a total area of 2,520 hectares. -

DIRECTORY of OPERATING MINES & QUARRIES, Region IX

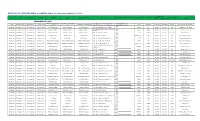

DIRECTORY OF OPERATING MINES & QUARRIES, Region IX - Zamboanga Peninsula CY 2016 Duration of Permit Location (Barangay, Municipality, Mineral Province Municipality/City Commodity Permit Holder Operator Managing Official/Position Mailing Address Telephone Number/Fax Number/E-mail Address Type of Permit Permit Number Effectivity of Area (hectares) Expiration of Permit Province) Permit ZAMBOANGA CITY (2016) Hard Rock Mineral Trading, Hard Rock Mineral Trading, Head Office - Unit 2A Traflgar Plaza Bldg, Tel Nr (032)253-0204; Fax Nr - Metallic Zamboanga Del Sur Zamboanga City Iron, Gold, Silver etc Mr. Jasper Karl T. ONG-President MPSA 237-2007-IX Jun 08, 2007 Jun 08, 2032 2,077.31 Cuatro Ojos, Vitali, Zamboanga City Inc./ATRO Inc. Salcedo Vill, Mkti; Mine Site - Zamboanga City _____________; Email addess - Tel______________@yahoo.,com Nr _______________________; Non-Metallic Zamboanga Del Sur Zamboanga City Sand and Gravel AGUSTIN, Alberto D AGUSTIN, Alberto D AGUSTIN, Alberto D Mine Site -Tulungatung River, Tulungatung CSAGP NP Jan 2016 Dec 2016 0.21 Tulungatung Rvr, Tulungatung Fax Nr - ________________________; Head Office - Bunguiao, Zambo. City; Mine Site - Tel Nr _______________________; Non-Metallic Zamboanga Del Sur Zamboanga City Sand and Gravel AGUILAR, Nazario P AGUILAR, Nazario P AGUILAR, Nazario P CSAGP 15-0019 Jan 2016 Dec 2016 1,500 Panubigan, Z.C. (Pvt Lot) Bunguiao, Z.C. Fax Nr - ________________________; Tel Nr _______________________; Non-Metallic Zamboanga Del Sur Zamboanga City Sand and Gravel ARQUIZA, Reynerio T. ARQUIZA, -

ABANTE BAYOG NEWS January-March 2018 the LCE’S CORNER

VOLUME II, ISSUE 1 JANUARY - M A R C H 2 0 1 8 BAYOG’S FIRST 90 DAYS FOR 2018 Bayog features “LITES En SHADES” LGU Bayog launched its new 12-point agenda last January 25, 2018 during a Community Party held at the Municipal Gymnasium with keynote speaker, Hon. Anto- nio H. Cerilles, Provincial Governor of the Province of Zamboanga del Sur attended by LGU officials and em- ployees, barangay officials and folks, DepEd Bayog Dis- trict and business sector. “LITES En SHADES” is the acronym of Law En- forcement, Infrastructure Development, Tourism Devel- opment, Employment Generation, Sports, Development, Environmental Protection, Solid Waste Management, Mayor Leonardo L. Babasa, Jr. presents “LITES En SHADES”, Health, Agriculture, Disaster Preparedness, Education, Bayog’s new 12-point agenda at the gymnasium. and Social Services. Moreover, other highlights of the program was the awarding of Performance Challenge Fund for Good Governance to the top 10 barangays where each received P500K worth of project and the Mass Oath-Taking of NGOs (Federated WEMRIC, Federated 4H Club, Federated Senior Citizens, and Federated Farmers). Top 10 barangays awarded with P5K Performance Challenge Fund with their corresponding rating: 1. Poblacion – 83.60% 6. Lamare – 70.60% 2. Balukbahan – 78.20% 7. Salawagan – 70.30% 3. Kahayagan – 72.60% 8. Dipili – 70.10% 4. Depore – 72.20% 9. Bobuan – 69.50% 5. Damit – 71.80% 10.Depase – 68.00% Federated WEMRIC Officers 2018 Federated 4H Club Officers 2018 President : Jocel L. Babasa President : Mercy P. Saura Vice President : Marlyn B. Lumido Vice President : Reynaldo C. Ruelo Secretary : Alma A.