1 Belarusian Political Parties: Organizational Structures And

Total Page:16

File Type:pdf, Size:1020Kb

Load more

Recommended publications

-

Belarus Country Report BTI 2014

BTI 2014 | Belarus Country Report Status Index 1-10 4.31 # 101 of 129 Political Transformation 1-10 3.93 # 99 of 129 Economic Transformation 1-10 4.68 # 90 of 129 Management Index 1-10 2.80 # 119 of 129 scale score rank trend This report is part of the Bertelsmann Stiftung’s Transformation Index (BTI) 2014. It covers the period from 31 January 2011 to 31 January 2013. The BTI assesses the transformation toward democracy and a market economy as well as the quality of political management in 129 countries. More on the BTI at http://www.bti-project.org. Please cite as follows: Bertelsmann Stiftung, BTI 2014 — Belarus Country Report. Gütersloh: Bertelsmann Stiftung, 2014. This work is licensed under a Creative Commons Attribution 4.0 International License. BTI 2014 | Belarus 2 Key Indicators Population M 9.5 HDI 0.793 GDP p.c. $ 15592.3 Pop. growth1 % p.a. -0.1 HDI rank of 187 50 Gini Index 26.5 Life expectancy years 70.7 UN Education Index 0.866 Poverty3 % 0.1 Urban population % 75.4 Gender inequality2 - Aid per capita $ 8.8 Sources: The World Bank, World Development Indicators 2013 | UNDP, Human Development Report 2013. Footnotes: (1) Average annual growth rate. (2) Gender Inequality Index (GII). (3) Percentage of population living on less than $2 a day. Executive Summary Belarus faced one the greatest challenges of the Lukashenka presidency with the economic shocks that swept the country in 2011. The government’s own policies of politically motivated increases in state salaries and directed lending resulted in a balance of payments crisis, a massive decrease in central bank reserves, a currency crisis as queues formed at banks to change Belarusian rubles into dollars or euros, rampant hyperinflation, a devaluation of the national currency, and a significant drop in real incomes for Belarusian households. -

Testimony :: Stephen Nix

Testimony :: Stephen Nix Regional Program Director, Eurasia - International Republican Institute Mr. Chairman, I wish to thank you for the opportunity to testify before the Commission today. We are on the eve of a presidential election in Belarus which holds vital importance for the people of Belarus. The government of the Republic of Belarus has the inherit mandate to hold elections which will ultimately voice the will of its people. Sadly, the government of Belarus has a track record of denying this responsibility to its people, its constitution, and the international community. Today, the citizens of Belarus are facing a nominal election in which their inherit right to choose their future will not be granted. The future of democracy in Belarus is of strategic importance; not only to its people, but to the success of the longevity of democracy in all the former Soviet republics. As we have witnessed in Georgia and Ukraine, it is inevitable that the time will come when the people stand up and demand their rightful place among their fellow citizens of democratic nations. How many more people must be imprisoned or fined or crushed before this time comes in Belarus? Mr. Chairman, the situation in Belarus is dire, but the beacon of hope in Belarus is shining. In the midst of repeated human rights violations and continual repression of freedoms, a coalition of pro-democratic activists has emerged and united to offer a voice for the oppressed. The courage, unselfishness and determination of this coalition are truly admirable. It is vitally important that the United States and Europe remain committed to their support of this democratic coalition; not only in the run up to the election, but post-election as well. -

No. 21 TRONDHEIM STUDIES on EAST EUROPEAN CULTURES

No. 21 TRONDHEIM STUDIES ON EAST EUROPEAN CULTURES & SOCIETIES David R. Marples THE LUKASHENKA PHENOMENON Elections, Propaganda, and the Foundations of Political Authority in Belarus August 2007 David R. Marples is University Professor at the Department of History & Classics, and Director of the Stasiuk Program for the Study of Contemporary Ukraine of the Canadian Institute of Ukrainian Studies, University of Alberta, Edmonton, Alberta, Canada. His recent books include Heroes and Villains. Constructing National History in Contemporary Ukraine (2007), Prospects for Democracy in Belarus, co-edited with Joerg Forbrig and Pavol Demes (2006), The Collapse of the Soviet Union, 1985-1991(2004), and Motherland: Russia in the 20th Century (2002). © 2007 David R Marples and the Program on East European Cultures and Societies, a program of the Faculties of Arts and Social Sciences, Norwegian University of Science and Technology. ISSN 1501-6684 ISBN 978-82-995792-1-6 Trondheim Studies on East European Cultures and Societies Editors: György Péteri and Sabrina P. Ramet Editorial Board: Trond Berge, Tanja Ellingsen, Knut Andreas Grimstad, Arne Halvorsen We encourage submissions to the Trondheim Studies on East European Cultures and Societies. Inclusion in the series will be based on anonymous review. Manuscripts are expected to be in English (exception is made for Norwegian Master’s and PhD theses) and not to exceed 150 double spaced pages in length. Postal address for submissions: Editor, Trondheim Studies on East European Cultures and Societies, Department of History, NTNU, NO-7491 Trondheim, Norway. For more information on PEECS and TSEECS, visit our web-site at http://www.hf.ntnu.no/peecs/home/ The photo on the cover is a copy of an item included in the photo chronicle of the demonstration of 21 July 2004 and made accessible by the Charter ’97 at http://www.charter97.org/index.phtml?sid=4&did=july21&lang=3 TRONDHEIM STUDIES ON EAST EUROPEAN CULTURES & SOCIETIES No. -

General Assembly Distr

UNITED A NATIONS General Assembly Distr. GENERAL A/HRC/4/16 15 January 2007 Original: ENGLISH HUMAN RIGHTS COUNCIL Fourth session Item 2 of the provisional agenda IMPLEMENTATION OF GENERAL ASSEMBLY RESOLUTION 60/251 OF 15 MARCH 2006 ENTITLED “HUMAN RIGHTS COUNCIL” Report of the Special Rapporteur on the situation of human rights in Belarus, Adrian Severin GE.07-10197 (E) 190107 A/HRC/4/16 page 2 Summary The mandate of the Special Rapporteur on the situation of human rights in Belarus was established by Commission on Human Rights resolution 2004/14 and extended by resolution 2005/13. In its decision 1/102 of 30 June 2006 the Human Rights Council requested the special procedures to continue with the implementation of their mandates. Among other things the Commission requested the Special Rapporteur to establish direct contacts with the Government and with the people of Belarus, with a view to examining the situation of human rights in Belarus. The Special Rapporteur regrets that the Government of Belarus, in 2006 as in 2004 and 2005, has not responded favourably to his request to visit the country and has in general not cooperated with him in the fulfilment of his mandate. Therefore, the report is based on the Special Rapporteur’s mission to the Russian Federation in early 2006 as well as discussions and consultations held in Geneva, Strasbourg and Brussels with representatives of permanent missions and non-governmental organizations, the United Nations and specialized agencies, the Organization for Security and Cooperation in Europe, and the Council of Europe. It is also based on media reports and various documentary sources. -

The EU and Belarus – a Relationship with Reservations Dr

BELARUS AND THE EU: FROM ISOLATION TOWARDS COOPERATION EDITED BY DR. HANS-GEORG WIECK AND STEPHAN MALERIUS VILNIUS 2011 UDK 327(476+4) Be-131 BELARUS AND THE EU: FROM ISOLATION TOWARDS COOPERATION Authors: Dr. Hans-Georg Wieck, Dr. Vitali Silitski, Dr. Kai-Olaf Lang, Dr. Martin Koopmann, Andrei Yahorau, Dr. Svetlana Matskevich, Valeri Fadeev, Dr. Andrei Kazakevich, Dr. Mikhail Pastukhou, Leonid Kalitenya, Alexander Chubrik Editors: Dr. Hans-Georg Wieck, Stephan Malerius This is a joint publication of the Centre for European Studies and the Konrad- Adenauer-Stiftung. This publication has received funding from the European Parliament. Sole responsibility for facts or opinions expressed in this publication rests with the authors. The Centre for European Studies, the Konrad-Adenauer- Stiftung and the European Parliament assume no responsibility either for the information contained in the publication or its subsequent use. ISBN 978-609-95320-1-1 © 2011, Konrad-Adenauer-Stiftung e.V., Sankt Augustin / Berlin © Front cover photo: Jan Brykczynski CONTENTS 5 | Consultancy PROJECT: BELARUS AND THE EU Dr. Hans-Georg Wieck 13 | BELARUS IN AN INTERnational CONTEXT Dr. Vitali Silitski 22 | THE EU and BELARUS – A Relationship WITH RESERvations Dr. Kai-Olaf Lang, Dr. Martin Koopmann 34 | CIVIL SOCIETY: AN analysis OF THE situation AND diRECTIONS FOR REFORM Andrei Yahorau 53 | Education IN BELARUS: REFORM AND COOPERation WITH THE EU Dr. Svetlana Matskevich 70 | State bodies, CONSTITUTIONAL REALITY AND FORMS OF RULE Valeri Fadeev 79 | JudiciaRY AND law -

English Version of This Report Is the Only Official Document

Office for Democratic Institutions and Human Rights REPUBLIC OF BELARUS PARLIAMENTARY ELECTIONS 23 September 2012 OSCE/ODIHR Election Observation Mission Final Report Warsaw 14 December 2012 TABLE OF CONTENTS I. EXECUTIVE SUMMARY................................................................................................1 II. INTRODUCTION AND ACKNOWLEDGEMENTS....................................................3 III. POLITICAL BACKGROUND.........................................................................................3 IV. LEGAL FRAMEWORK AND ELECTORAL SYSTEM..............................................4 V. ELECTION ADMINISTRATION ...................................................................................5 A. CENTRAL ELECTION COMMISSION.....................................................................................6 B. DISTRICT AND PRECINCT ELECTION COMMISSIONS..........................................................7 VI. VOTER REGISTRATION ...............................................................................................7 VII. CANDIDATE REGISTRATION .....................................................................................8 VIII. ELECTION CAMPAIGN ...............................................................................................10 A. CAMPAIGN ENVIRONMENT................................................................................................10 B. CAMPAIGN FINANCE..........................................................................................................12 -

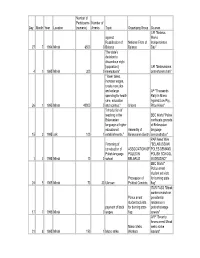

Protests in Belarus (1994-2011) .Pdf

Number of Participants Number of Day Month Year Location (numeric) Arrests Topic Organizing Group Sources UPI "Belarus against Marks Russification of National Front of Independence 27 7 1994 Minsk 6500 0 Belarus Belarus Day" "the state's decision to discontinue eight [opposition] UPI "Belarussians 4 1 1995 Minsk 300 0 newspapers" protest press ban" " lower taxes, increase wages, create new jobs and enlarge AP "Thousands spending for health Rally In Minsk care, education Against Low Pay, 26 1 1995 Minsk 40000 0 and science." Unions Price Hikes" "introduction of teaching in the BBC World "Police Belarussian confiscate grenade language at higher at Belarussian educational Assembly of language 15 2 1995 unk 100 1 establishments," Belarussian Gentry demonstration" PAP News Wire Financing of "BELARUSSIAN construction of ASSOCIATION OF POLES DEMAND Polish language POLES IN POLISH SCHOOL 1 3 1995 Minsk 10 0 school BELARUS IN GRODNO" BBC World " Police arrest student activists Procession of for burning state 24 5 1995 Minsk 70 30 Uknown Political Convicts flag" ITAR-TASS "Minsk workers march on Police arrest presidential student activists residence in payment of back for burning state protest at wage 17 7 1995 Minsk . 0 wages flag arrears" AFP "Security forces arrest Minsk Minsk Metro metro strike 21 8 1995 Minsk 150 1 Metro strike Workers leaders" Number of Participants Number of Day Month Year Location (numeric) Arrests Topic Organizing Group Sources Interfax "Belarusian Popular Front Reconsideration of protests against oil oil agreement with -

Warsaw East European Review Review European East Warsaw More Information on Recruitment: Volume I1/2012

Warsaw East European Conference vol. ii/2012 • In the academic year 2012/2013 THE CENTRE FOR EAST EUROPEAN STUDIES will be inviting applications for the following scholarship programs: ◆ The Kalinowski Scholarship Program ◆ Scholarships of the Polish Government for Young Academicians ◆ 25 scholarships to enter the 2-year Master’s Program in Specialist Eastern Studies ◆ The Lane Kirkland Scholarship Program Warsaw East ◆ The Krzysztof Skubiszewski Scholarship European Review Warsaw East European Review Review European East Warsaw More information on recruitment: www.studium.uw.edu.pl volume i1/2012 R Warsaw East European Conference Okl_Warsaw East European Review 2012.indd 1 2012-07-09 08:27:20 e W E E R / Warsaw East European Conferenc e W E E R / Warsaw East European Conferenc INTERNAT I ONAL BOARD : Egidijus Aleksandravičius, Vytautas Magnus University Stefano Bianchini, University of Bologna Miroslav Hroch, Charles University Yaroslav Hrytsak, Ukrainian Catholic University Andreas Kappeler, University of Vienna Zbigniew Kruszewski, University of Texas, El Paso Jan Kubik, Rutgers University Alexey Miller, Russian Academy of Sciences Richard Pipes, Harvard University Mykola Riabchuk, Kyiv-Mohyla Academy Alexander Rondeli, Georgian Foundation for Strategic and International Studies John Micgiel, Columbia University Barbara Törnquist-Plewa, Lund University Theodore Weeks, Southern Illinois University ED I TOR I AL COMM I TTEE : Jan Malicki, University of Warsaw (Director of the WEEC – Warsaw East European Conference, chair of the Committee) Leszek Zasztowt (chair of the WEEC Board), University of Warsaw Andrzej Żbikowski (secretary of the WEEC Board, University of Warsaw ED I TOR -I N -CH I EF Jerzy Kozakiewicz, University of Warsaw ASS I STANT ED I TOR Konrad Zasztowt, University of Warsaw ISBN: 978-83-61325-239 ISSN: 2299-2421 Copyright © by Studium Europy Wschodniej UW 2012 COVER AND TYPOGRAPH ic DES I GN J.M & J.J.M. -

Truth Stumbles in the Street Christian Democratic Activism in Belarus

Truth Stumbles in the Street Christian Democratic Activism in Belarus Geraldine Fagan Abstract: Few are aware that prominent figures in the Belarusian opposition movement are motivated by Christian conviction. In this article, the author trac- es how President Alexander Lukashenko’s restriction of religious freedom has prompted Catholics, Orthodox, and Protestants to turn toward democratic activ- ism; it also discusses their rediscovery of religious freedom as a long-standing core value of Belarusian identity. The author’s findings draw on interviews con- ducted in Minsk in the aftermath of the December 2010 presidential election, including those with Christian opposition activists who were subsequently jailed. Keywords: Belarus, democracy, freedom, religion nce a dictatorial regime has muzzled civil society’s more cantankerous O elements—rival political parties and the independent media—a stage is reached at which faith groups, even if falteringly, join the vanguard in the struggle for freedom and justice. In 1980s Communist Poland, the Catholic Church offered a vital moral platform for mass dissent by the Solidarity movement. Prayer meetings at a Leipzig Lutheran church formed the nucleus of protest by hundreds of thousands of East Germans in the weeks before the Berlin Wall fell in 1989. Might faith-inspired opposition similarly prove a catalyst for political change in Belarus, dubbed “the last true dictatorship in the center of Europe” by United States Secretary of State Condoleezza Rice in 2005?1 The prospects Geraldine Fagan is a 2010–2011 Joseph R. Crapa Fellow at the United States Commission on International Religious Freedom. She has monitored religious freedom in Belarus since 2003 as the Moscow correspondent for Forum 18 News Service. -

Belarusian Opposition Presidential Candidate Sviatlana Tsikhanouskaya

Thank you, Mr. Chairman, Today my country, Belarus, is in turmoil. Peaceful protesters are being illegally detained, beaten, and imprisoned. The protests themselves started after a cynical and blatant attempt by Mr. Lukashenko to steal the votes of the people. The demands of the nation are simple: immediate termination of violence and threats by the regime, immediate release of all political prisoners, and free and fair election. There is only one obstacle to these demands being met. This obstacle is Mr. Lukashenko, a man desperately clinging onto power and refusing to listen to his people and his own state officials. A nation can not and should not be a hostage to one man's thirst for power. And it won't. Belarusians have woken up. The point of no return has passed. This is manifested by now daily demonstrations of hundreds of thousands all across Belarus, despite police brutality and blatant disregard for Belarusian laws and international norms. This is manifested by the strikes across the largest factories and state-owned companies in Belarus, despite intimidation and in some cases unlawful layoffs. This is manifested by all the strata of our society and all the political spectrum demanding the one and the same thing. The regime of Alexander Lukashenko is morally bankrupt, legally questionable and simply untenable in the eyes of our nation. The United Nations was created as a formal body of the whole international community in order to promote and encourage respect for human rights and for fundamental freedoms for all. In 1945 Belarus was one of the founding members of the United Nations. -

Belarusian Subject Collection

http://oac.cdlib.org/findaid/ark:/13030/tf7290058v No online items Inventory of the Belarusian subject collection Finding aid prepared by Ronald Bulatoff Hoover Institution Library and Archives © 1998 434 Galvez Mall Stanford University Stanford, CA 94305-6003 [email protected] URL: http://www.hoover.org/library-and-archives Inventory of the Belarusian XX800 1 subject collection Title: Belarusian subject collection Date (inclusive): 1938-2016 Collection Number: XX800 Contributing Institution: Hoover Institution Library and Archives Language of Material: In Belarusian and Russian Physical Description: 11 manuscript boxes, 2 oversize boxes, 4 CD-Rs(7.3 Linear Feet) Abstract: Pamphlets, serial issues, flyers, leaflets, election campaign literature, and other printed matter relating to various aspects of Belarusian history, and to political conditions and elections in Belarus following establishment of its independence. Hoover Institution Library & Archives Access Box 13 restricted; use copies available in Box 11. The remainder of the collection is open for research; materials must be requested at least two business days in advance of intended use. Publication Rights For copyright status, please contact the Hoover Institution Library & Archives. Acquisition Information Acquired by the Hoover Institution Library & Archives. An increment was added in 2011. Preferred Citation [Identification of item], Belarusian subject collection, [Box no., Folder no. or title], Hoover Institution Library & Archives. Scope and Content of Collection Pamphlets, serial issues, flyers, leaflets, election campaign literature, and other printed matter relating to various aspects of Belarusian history, and to political conditions and elections in Belarus following establishment of its independence. An increment received in 2011 contains campaign material from the Belarusian presidential election of December 2010. -

BELARUS Restrictions on the Political and Civil Rights of Citizens Following the 2010 Presidential Election

BELARUS Restrictions on the Political and Civil Rights of Citizens Following the 2010 Presidential Election of person. Article 4: No one shall be held in slavery Article 1: All human beings are born free and equal or servitude; slavery and the slave trade shall be prohibited in all their forms. Article 5: No one shall be subjected to in dignity and rights. They are endowed with reason and conscience and should act towards one another in a torture or to cruel, inhuman or degrading treatment or punishment. Article 6: Everyone has the right to recognition spirit of brotherhood. Article 2: Everyone is entitled to all the rights and freedoms set forth in this Declaration, everywhere as a person before the law. Article 7: All are equal before the law and are entitled without any discrimi- without distinction of any kind, such as race, colour, sex, language, religion, political or other opinion, nation to equal protection of the law. All are entitled to equal protection against any discrimination in violation of this national or social origin, property, birth or other status. Furthermore, no distinction shall be made on the Declaration and against any incitement to such discrimination. Article 8: Everyone has the right to an effective rem- basis of the political, jurisdictional or international status of the country or territory to which a person edy by the competent national tribunals for acts violating the fundamental rights granted him by the constitution or belongs, whether it be independent, trust, non-self-governing or under any other limitation of sovereignty. by law. Article 9: No one shall be subjected to arbitrary arrest, Article 3: Everyone has the right to life, liberty and security June 2011 564a Uladz Hrydzin © This report has been produced with the support of the Swedish International Development Cooperation Agency (SIDA).