University of Copenhagen

Total Page:16

File Type:pdf, Size:1020Kb

Load more

Recommended publications

-

Alexander the Great and Hephaestion

2019-3337-AJHIS-HIS 1 Alexander the Great and Hephaestion: 2 Censorship and Bisexual Erasure in Post-Macedonian 3 Society 4 5 6 Same-sex relations were common in ancient Greece and having both male and female 7 physical relationships was a cultural norm. However, Alexander the Great is almost 8 always portrayed in modern depictions as heterosexual, and the disappearance of his 9 life-partner Hephaestion is all but complete in ancient literature. Five full primary 10 source biographies of Alexander have survived from antiquity, making it possible to 11 observe the way scholars, popular writers and filmmakers from the Victorian era 12 forward have interpreted this evidence. This research borrows an approach from 13 gender studies, using the phenomenon of bisexual erasure to contribute a new 14 understanding for missing information regarding the relationship between Alexander 15 and his life-partner Hephaestion. In Greek and Macedonian society, pederasty was the 16 norm, and boys and men did not have relations with others of the same age because 17 there was almost always a financial and power difference. Hephaestion was taller and 18 more handsome than Alexander, so it might have appeared that he held the power in 19 their relationship. The hypothesis put forward here suggests that writers have erased 20 the sexual partnership between Alexander and Hephaestion because their relationship 21 did not fit the norm of acceptable pederasty as practiced in Greek and Macedonian 22 culture or was no longer socially acceptable in the Roman contexts of the ancient 23 historians. Ancient biographers may have conducted censorship to conceal any 24 implication of femininity or submissiveness in this relationship. -

Ancient Cyprus: Island of Conflict?

Ancient Cyprus: Island of Conflict? Maria Natasha Ioannou Thesis submitted for the degree of Master of Philosophy Discipline of Classics School of Humanities The University of Adelaide December 2012 Table of Contents Abstract ................................................................................................................ III Declaration........................................................................................................... IV Acknowledgements ............................................................................................. V Introduction ........................................................................................................... 1 1. Overview .......................................................................................................... 1 2. Background and Context ................................................................................. 1 3. Thesis Aims ..................................................................................................... 3 4. Thesis Summary .............................................................................................. 4 5. Literature Review ............................................................................................. 6 Chapter 1: Cyprus Considered .......................................................................... 14 1.1 Cyprus’ Internal Dynamics ........................................................................... 15 1.2 Cyprus, Phoenicia and Egypt ..................................................................... -

JOURNAL of ALEXANDER the GREAT RESOURCES Childhood

JOURNAL OF ALEXANDER THE GREAT RESOURCES Childhood and Education http://www.livius.org/sources/content/plutarch/plutarchs-alexander/alexander-and-aristotle/ https://www.awesomestories.com/asset/view/LEARNING-FROM-ARISTOTLE-Alexander-the-Great http://www.independent.co.uk/news/world/world-history/aristotle-and-alexander-the-man-who- codified-greek-ideas-about-nature-and-the-man-who-spread-them-1608033.html http://www.biography.com/people/alexander-the-great-9180468#early-life Relationship with Bucephalus http://www.livius.org/sources/content/plutarch/plutarchs-alexander/alexander-and-bucephalus/ http://www.theequinest.com/bucephalus/ http://ancienthistory.about.com/od/alexander/g/Bucephalus.htm http://www.ancient.eu/Bucephalus/ Role in his father’s army http://warfarehistorynetwork.com/daily/military-history/macedonias-elite-companion-cavalry-under- alexander-the-great/ http://www.livius.org/sources/content/diodorus/the-battle-of-chaeronea/ Battle of Thebes http://www.livius.org/sources/content/diodorus/the-sack-of-thebes/ https://thesecondachilles.com/2014/06/27/the-fall-of-thebes/ http://thegreatcommanders.com/destruction_thebes.html Battle of Granicus River http://www.ancient.eu/Battle_of_the_Granicus/ http://www.livius.org/sources/content/plutarch/plutarchs-alexander/battle-on-the-granicus/ http://web.ics.purdue.edu/~rauhn/Hist303/Battle%20of%20the%20Granicus%20River%20334%20BC.ht m Battle of Issus http://alexandermosaik.de/en/battle_of_issus.html http://www.livius.org/sources/content/diodorus/the-battle-of-issus/ http://greatmilitarybattles.com/Battle%20of%20Issus.htm -

Imitation of Greatness: Alexander of Macedon and His Influence on Leading Romans

Imitation of Greatness: Alexander of Macedon and His Influence on Leading Romans Thomas W Foster II, McNair Scholar The Pennsylvania State University Mark Munn, Ph.D Head, Department of Classics and Ancient Mediterranean Studies College of Liberal Arts The Pennsylvania State University Abstract This paper seeks to examine the relationship between greatness and imitation in antiquity. To do so, Alexander the Great will be compared with Romans Julius Caesar and Marcus Aurelius. The question this paper tries to answer concerns leading Romans and the idea of imitating Alexander the Great and how this affected their actions. It draws upon both ancient sources and modern scholarship. It differs from both ancient and modern attempts at comparison in distinct ways, however. This paper contains elements of the following: historiography, biography, military history, political science, character study, religion and socio-cultural traditions. Special attention has been given to the socio-cultural differences of the Greco-Roman world. Comparing multiple eras allows for the establishment of credible commonalities. These commonalities can then be applied to different eras up to and including the modern. Practically, these traits allow us to link these men of antiquity, both explicitly and implicitly. Beginning with Plutarch in the 1st/2nd century CE1, a long historical tradition of comparing great men was established. Plutarch chose to compare Alexander the Great to Julius Caesar. The reasons for such a comparison are quite obvious. Both men conquered swaths of land, changed the balance of power in the Mediterranean and caused many to either love them or plot to kill them. Scholars have assessed this comparison continuously. -

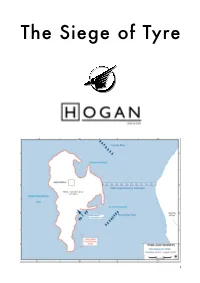

The Siege of Tyre

The Siege of Tyre 1 Contents Past Questions! 2 Arrian’s Account Of The Siege! 4 Key Points! 14 Past Questions 1985 Give Alexander's reasons for besieging Tyre and describe the siege. What does the siege tell us about Alexander's character? (50) 1991 "Alexander had no difficulty in persuading his officers that the attempt on Tyre must be made". (Arrian, Book 2. Ch. 18) What arguments did Alexander use to persuade his officers? What factors made the siege of Tyre “a tremendous undertaking"? (50) 1995 2 What particular skills did Alexander show in his sieges of Halicarnassus and Tyre? (50) 2004 (ii) The siege and capture of Tyre has been described as Perhaps the hardest task that Alexander’s military genius ever encountered. (Bury and Meiggs) (a) What were the main challenges presented by Tyre and its defenders, and how did Alexander’s genius overcome those challenges? (40) (b) What is your opinion of Alexander’s treatment of the survivors after the capture of Tyre? (10) 2012 (ii) (a) Explain why the city of Tyre was so difficult to capture. (15) (b) How did Alexander overcome the difficulties presented by Tyre and its defenders? (25) (c) What do you learn about Alexander’s character from Arrian’s account of the siege and capture of Tyre? (10) 3 Arrian’s Account Of The Siege • Alexander easily persuaded his men to make an attack on Tyre. An omen helped to convince him, because that very night during a dream he seemed to be approaching the walls of Tyre, and Heracles was stretching out his right hand towards him and leading him to the city. -

Causes of the Rise in Violence in the Eastern Campaigns of Alexander the Great

“Just Rage”: Causes of the Rise in Violence in the Eastern Campaigns of Alexander the Great _______________________________________ A Thesis presented to the Faculty of the Graduate School at the University of Missouri-Columbia _____________________________________________________ In Partial Fulfillment of the Requirements for the Degree Master of Arts _____________________________________________________ by Jenna Rice MAY 2014 The undersigned, appointed by the dean of the Graduate School, have examined the thesis entitled “JUST RAGE”: CAUSES OF THE RISE IN VIOLENCE IN THE EASTERN CAMPAIGNS OF ALEXANDER THE GREAT presented by Jenna Rice, a candidate for the degree of master of history, and hereby certify that, in their opinion, it is worthy of acceptance. Professor Ian Worthington Professor Lawrence Okamura Professor LeeAnn Whites Professor Michael Barnes τῷ πατρί, ὅς ἐμοί τ'ἐπίστευε καὶ ἐπεκέλευε ACKNOWLEDGEMENTS I would like to thank the members of my committee, Professors Worthington, Okamura, Whites, and Barnes, for the time they spent reading and considering my thesis during such a busy part of the semester. I received a number of thoughtful questions and suggestions of new methodologies which will prompt further research of my topic in the future. I am especially grateful to my advisor, Professor Worthington, for reading through and assessing many drafts of many chapters and for his willingness to discuss and debate the topic at length. I know that the advice I received throughout the editing process will serve me well in future research endeavors. ii TABLE OF CONTENTS LIST OF ABBREVIATIONS ............................................................................................ iv INTRODUCTION ...............................................................................................................1 Chapter 1. THE GREEK RULES OF WAR ..............................................................................5 2. ALEXANDER IN PERSIA ...................................................................................22 3. -

Alexander the Great and Hellenization

Thornton I Alexander I 25 Alexander the Great and Hellenization by Larry R Thornton, ThD Professor, Calvary Baptist Theological Seminary Historians have differed in their presentations and evaluations of Alex ander the Great and his relation to Hellenism. It is not the purpose here to settle any of these questions. The aim of this article is to set forth the life of Alexander the Great in a brief sketch, to consider his achievements and motives as they relate to Hellenization, and to notice his conduct and achievements in light of God's prophecies and providence. The people of Greece produced a culture that influenced the known world. The process of Hellenization began early "as a natural and un premeditated admiration, unsponsored and unencouraged:'1 Archeological evidence exists for contacts between the Aegean and Mesopotamia as far back as the third millennium. In the late Bronze Age (1500-1200 BC) Greek traders sold products around the Mediterranean Sea. The influence or acceptance of Greek culture has been described as "Hellenistic" rather than "Hellenic" because the results were not purely Greek, but a mixture of Greek culture with the culture of the natives. It has been likened to a cultural veneer varying in thickness with the willingness or eagerness of natives to drink at the well of Greek culture. "But, mixed as the civiliza tion was it was yet Greek in its appearance, and it followed Greek models, and so it remained" writes A W Blunt. 2 Thus it may be observed that the Hellenization process did not begin with Alexander the Great. -

Chronology of Important Dates and Events 1187 BCE Capture of Troy

Chronology of important dates and events 1187 B.C.E. Capture of Troy 559-530 Reign of Cyrus II, the Great 499-494 Revolt of Ionian Greeks 490 September Persian defeat at Marathon 480 September Destruction of the temples on the Acropolis of Athens; Persian defeat at Salamis 479 Persian defeat at Plataea 450 Peace of Kallias 431-404 Peloponnesian War 387/6 “King’s Peace” 382 birth of Philip II 380 Panegyricus of Isocrates 371 July Battle of Leuctra 369-367 Philip II hostage in Thebes 362 Battle of Mantinea 360/59 death of Perdiccas III (brother of Philip II) 356 20 July birth of Alexander III 346 Isocrates’ letter To Philip 338 August Battle of Chaeronea 336 spring Macedonian Expeditionary force crosses Hellespont 336 October assassination of Philip II 334 late spring Battle of the Granicus River 334 early summer Alexander in Ephesos 334 summer capture of Miletos 334 summer siege of Halicarnassus 334/3 winter Alexander’s campaigns in Caria, Lycia, Pamphylia, Phrygia 333 spring Memnon’s naval offensive 333 spring/summer Alexander in Gordium, campaigns in area 333 late summer Alexander into Cilicia 333 end of summer Alexander in Tarsus 333 September Darius in the Amik plain 333 November Battle of Issos 332 January-July Siege of Tyre 332 Sept.-November Siege of Gaza 331 late winter Alexander’s visit to Siwah 331 7 April Inauguration of Alexandria 331 spring Alexander in Memphis 331 April Alexander leaves Memphis 331 9 pm 20 Sept. Eclipse of moon after Alexander crosses Tigris 331 1 October Battle of Gaugamela 331 end of Nov. -

CLASSICAL STUDIES Tadhg Machugh Classical Studies HIGHER LEVEL 2020/21

CLASSICAL STUDIES Tadhg MacHugh Classical Studies HIGHER LEVEL 2020/21 ALEXANDER THE GREAT-GREAT BATTLES CONTENTS FORMAT NOTE 1 PAST QUESTIONS BREAKDOWN 2 BATTLE OF GRANICUS 3-10 BATTLE OF ISSUS 11-19 BATTLE OF GAUGAMELA 20-26 BATTEL OF HYDASPES 27-32 LETTERS FORM DARIUS TO ALEXANDER 33-34 NAME. SUBJECT. CYCLE. YEAR. Format: - The booklet has been broken into sub-categories based on past questions. - Each category will be presented with a breakdown of past questions. - It is important to utilize apps such as pocket papers or https://www.examinations.ie/exammaterialarchive/?i=115.120.111.100.99 Sub-Categories: - Battles - Key Events - Sieges - NB: Character: we will be building evidence of Alexanders character from these other sub-categories. - Character is based on three concepts; what a character does, says, and what others say about them. - 1 NAME. SUBJECT. CYCLE. YEAR. ALEXANDER THE GREAT BATTLES 1996: Hydaspes 1997: N/A 1998: Gaugamela 1999: N/A 2000: Granicus 2001: N/A 2002: Issus 2003: N/A 2004: N/A 2005: Gaugamela 2006: Issus 2007: Hydaspes 2008: Issus 2009: Granicus 2010: Gaugamela 2011: Hydaspes 2012: N/A 2013: Issus 2014: Granicus 2015: Gaugamela 2016: N/A 2017: Hydaspese 2018: Issus 2019: Granicus Advisable to know Gaugamela and Hydaspes equally well 2 NAME. SUBJECT. CYCLE. YEAR. Battle of Granicus 334 BC PAST QUESTIONS: 2000: The Persian leaders including Memnon of Rhodes, met to decide how to deal with Alexander shortly after his arrival in Asia Minor. (a) What options did they discuss, and why did they decide to meet Alexander in battle at the river Granicus? (20) (b) Give a brief outline of the course of this battle (30) 2009: At the Granicus River Alexander won his first victory over a Persian army. -

Time and Religion in Hellenistic Athens: an Interpretation of the Little Metropolis Frieze

Time and Religion in Hellenistic Athens: An Interpretation of the Little Metropolis Frieze. Monica Haysom School of History, Classics and Archaeology Submitted for the Degree of Doctor of Philosophy, Newcastle University, November 2015. ABSTRACT Two stones that form a part of the spolia on the Little Metropolis church (Aghios Eleutherios) in central Athens consist of a frieze depicting a calendar year. The thesis begins with a Preface that discusses the theoretical approaches used. An Introduction follows which, for reference, presents the 41 images on the frieze using the 1932 interpretation of Ludwig Deubner. After evaluating previous studies in Chapter 1, the thesis then presents an exploration of the cultural aspects of time in ancient Greece (Chapter 2). A new analysis of the frieze, based on ancient astronomy, dates the frieze to the late Hellenistic period (Chapter 3); a broad study of Hellenistic calendars identifies it as Macedonian (Chapter 4), and suggests its original location and sponsor (Chapter 5). The thesis presents an interpretation of the frieze that brings the conclusions of these chapters together, developing an argument that includes the art, religion and philosophy of Athenian society contemporary with the construction of the frieze. Given the date, the Macedonian connection and the link with an educational establishment, the final Chapter 6 presents an interpretation based not on the addition of individual images but on the frieze subject matter as a whole. This chapter shows that understanding the frieze is dependent on a number of aspects of the world of artistic connoisseurship in an elite, educated audience of the late Hellenistic period. -

Unconventional Weapons, Siege Warfare, and the Hoplite Ideal

Unconventional Weapons, Siege Warfare, and the Hoplite Ideal Thesis Presented in Partial Fulfillment of the Requirements for the Degree Masters of Arts in the Graduate School of The Ohio State University By Amanda S. Morton, B.A. Graduate Program in History The Ohio State University 2011 Thesis Committee: Gregory Anderson, Advisor Timothy Gregory Nathan Rosenstein Copyright by Amanda S. Morton 2011 Abstract This paper examines the introduction of unconventional siege tactics, namely the use of chemical and biological weapons, during the Peloponnesian War in an effort to add to an existing body of work on conventional and unconventional tactics in Greek hoplite warfare. This paper argues that the characteristics of siege warfare in the mid-fifth century exist in opposition to traditional definitions of Greek hoplite warfare and should be integrated into the ongoing discussion on warfare in the fifth century. The use of siege warfare in Greece expanded dramatically during the Peloponnesian War, but these sieges differed from earlier Greek uses of blockade tactics, utilizing fire, poisonous gasses and new types of siege machinery that would eventually lead to a Hellenistic period characterized by inventive and expedient developments in siege warfare. ii Acknowledgements I would like to thank Dr. Gregory Anderson, Dr. Nathan Rosenstein and Dr. Timothy Gregory for their guidance and assistance in the production of this paper. In particular, Dr. Anderson’s patience and guidance in the initial stages of this project were essential to its conception and completion. I would also like to thank Dr. David Staley for his research suggestions and for his encouragements to engage in projects that helped shape my research. -

Hellenistic Period

Advisory Board: Hillel Geva, Israel Exploration Society Alan Paris, Israel Exploration Society Contributing Authors: Itzhaq Beit-Arieh, Tel Aviv University Amnon Ben-Tor, Hebrew University of Jerusalem Andrea M. Berlin, Boston University Piotr Bienkowski, Cultural Heritage Museums, Lancaster, UK Trude Dothan, Hebrew University of Jerusalem Liora Freud, Tel Aviv University Ayelet Gilboa, Haifa University Seymour Gitin, W.F. Albright Institute of Archaeological Research Larry G. Herr, Burman University Zeºev Herzog, Tel Aviv University Gunnar Lehmann, Ben-Gurion University of the Negev Amihai Mazar, Hebrew University of Jerusalem Eliezer D. Oren, Ben-Gurion University of the Negev Renate Rosenthal-Heginbottom, Tel Dor Excavation Project Lily Singer-Avitz, Tel Aviv University Ephraim Stern, Hebrew University of Jerusalem Ron E. Tappy, Pittsburgh Theological Seminary Jane C. Waldbaum, University of Wisconsin-Milwaukee Anabel Zarzecki-Peleg, Hebrew University of Jerusalem Alexander Zukerman, W.F. Albright Institute of Archaeological Research Copyright © 2015 Israel Exploration Society ISBN 978-965-221-102-6 (Set) ISBN 978-965-221-104-0 (Vol. 2) Layout: Avraham Pladot Typesetting: Marzel A.S. — Jerusalem Printing: Old City Press Ltd. Jerusalem PUBLICATION OF THIS VOLUME WAS MADE POSSIBLE BY THE GENEROUS CONTRIBUTIONS OF Lila Gruber Research Foundation Dorot Foundation Museum of the Bible John Camp Richard Elman Shelby White P.E. MacAllister Richard J. Scheuer Foundation David and Jemima Jeselsohn Jeannette and Jonathan Rosen Leon Levy Bequest allocated by Shelby White and Elizabeth Moynihan George Blumenthal Samuel H. Kress Foundation Joukowsky Family Foundation Paige Patterson, Southwestern Baptist Theological Seminary Judy and Michael Steinhardt David Rosenstein Contents Preface...................................................1 Editor’s Notes ................................................3 Seymour Gitin Volume 1 CHAPTER 1.1 Iron Age I: Northern Coastal Plain, Galilee, Samaria, Jezreel Valley, Judah, and Negev .