1 “Race Was a Motivating Factor”: the Rise of Re

Total Page:16

File Type:pdf, Size:1020Kb

Load more

Recommended publications

-

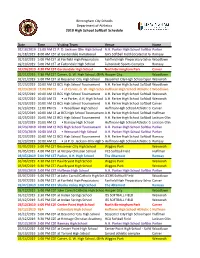

2019 High School Softball Master

Birmingham City Schools Department of Athletics 2019 High School Softball Schedule Date Time Visiting Team Venue Home 02/18/2019 11:00 AM CSTP. D. Jackson-Olin High School A.H. Parker High School SoftballParker 02/18/2019 8:00 AM CST at Gardendale Invitational GHS Softball Field (located at GardendaleRamsay H.S. beside Bragg) 02/19/2019 5:00 PM CST at Fairfield High Preparatory Fairfield High Preparatory SchoolWoodlawn Stadium 02/19/2019 5:00 PM CST at Fultondale High School Fultondale Sports Complex Ramsay 02/20/2019 4:30 PM CST Gardendale High School North Birmingham Park Carver 02/21/2019 7:30 PM CST Carver, G. W. High School, (BHM)Hooper City Woodlawn 02/21/2019 5:00 PM CST at Bessemer City High School Bessemer City High School SportsplexWenonah 02/23/2019 10:00 AM CSTBCS High School Tournament A.H. Parker High School Softball Woodlawn 02/23/2019 12:00 PM CST • at Carver, G. W. High School,Huffman (BHM) High School Athletic ComplexWoodlawn 02/23/2019 10:00 AM CSTBCS High School Tournament A.H. Parker High School Softball Wenonah 02/23/2019 10:00 AM CST • at Parker, A.H. High School A.H. Parker High School Softball Wenonah 02/23/2019 10:00 AM CSTBCS High School Tournament A.H. Parker High School Softball Carver 02/23/2019 12:00 PM CST • Woodlawn High School Huffman High School Athletic ComplexCarver 02/23/2019 10:00 AM CSTat BCS High School Tournament A.H. Parker High School Softball Huffman 02/23/2019 10:00 AM CSTBCS High School Tournament A.H. -

NGPF's 2021 State of Financial Education Report

11 ++ 2020-2021 $$ xx %% NGPF’s 2021 State of Financial == Education Report ¢¢ Who Has Access to Financial Education in America Today? In the 2020-2021 school year, nearly 7 out of 10 students across U.S. high schools had access to a standalone Personal Finance course. 2.4M (1 in 5 U.S. high school students) were guaranteed to take the course prior to graduation. GOLD STANDARD GOLD STANDARD (NATIONWIDE) (OUTSIDE GUARANTEE STATES)* In public U.S. high schools, In public U.S. high schools, 1 IN 5 1 IN 9 $$ students were guaranteed to take a students were guaranteed to take a W-4 standalone Personal Finance course standalone Personal Finance course W-4 prior to graduation. prior to graduation. STATE POLICY IMPACTS NATIONWIDE ACCESS (GOLD + SILVER STANDARD) Currently, In public U.S. high schools, = 7 IN = 7 10 states have or are implementing statewide guarantees for a standalone students have access to or are ¢ guaranteed to take a standalone ¢ Personal Finance course for all high school students. North Carolina and Mississippi Personal Finance course prior are currently implementing. to graduation. How states are guaranteeing Personal Finance for their students: In 2018, the Mississippi Department of Education Signed in 2018, North Carolina’s legislation echoes created a 1-year College & Career Readiness (CCR) neighboring state Virginia’s, by which all students take Course for the entering freshman class of the one semester of Economics and one semester of 2018-2019 school year. The course combines Personal Finance. All North Carolina high school one semester of career exploration and college students, beginning with the graduating class of 2024, transition preparation with one semester of will take a 1-year Economics and Personal Finance Personal Finance. -

Hinders Desegregation by Permitting School District Secessions

Whiter and Wealthier: “Local Control” Hinders Desegregation by Permitting School District Secessions MEAGHAN E. BRENNAN* When a school district is placed under a desegregation order, it is to be monitored by the district court that placed the order until the district is declared unitary. Many school districts have been under desegregation orders since shortly after Brown v. Board, but have failed to desegregate. Even when a school district is making an honest attempt, fulfilling a de- segregation order is difficult. These attempts can be further complicated when a racially-identifiable set of schools secedes from the district. Such school district disaggregations make traditional desegregation remedies more difficult by further isolating children of different races. In the past few decades, dozens of school districts have seceded to create wealthy districts filled with white children adjacent to poorer districts with children of color. This Note argues that school district secessions harm desegregation efforts and, in turn, the educational achievement of students in those districts. Two school districts — one in Jefferson Coun- ty, Alabama and another in Hamilton County, Tennessee — serve as ex- amples of how secession movements arise and how the conversations pro- gress. Secession proponents often advocate for increased “local control” — seemingly innocuous rhetoric that serves as a guise for racism and other prejudice. This Note argues that school district disaggregation is made far too easy by judicial preoccupation with local control and by the moral- political failure of state legislatures. But it is possible to discourage segre- gative school district disaggregation by reworking the concept of local con- trol so that it prioritizes all children, and by adopting state legislation that promotes consolidated, efficient school districts. -

High Schools in Alabama Within a 250 Mile Radius of Middle Tennessee State University

High Schools in Alabama within a 250 mile radius of Middle Tennessee State University CEEB High School Name City Zip Code CEEB High School Name City Zip Code 010395 A H Parker High School Birmingham 35204 012560 B B Comer Memorial School Sylacauga 35150 012001 Abundant Life School Northport 35476 012051 Ballard Christian School Auburn 36830 012751 Acts Academy Valley 36854 012050 Beauregard High School Opelika 36804 010010 Addison High School Addison 35540 012343 Belgreen High School Russellville 35653 010017 Akron High School Akron 35441 010035 Benjamin Russell High School Alexander City 35010 011869 Alabama Christian Academy Montgomery 36109 010300 Berry High School Berry 35546 012579 Alabama School For The Blind Talladega 35161 010306 Bessemer Academy Bessemer 35022 012581 Alabama School For The Deaf Talladega 35161 010784 Beth Haven Christian Academy Crossville 35962 010326 Alabama School Of Fine Arts Birmingham 35203 011389 Bethel Baptist School Hartselle 35640 010418 Alabama Youth Ser Chlkvlle Cam Birmingham 35220 012428 Bethel Church School Selma 36701 012510 Albert P Brewer High School Somerville 35670 011503 Bethlehem Baptist Church Sch Hazel Green 35750 010025 Albertville High School Albertville 35950 010445 Beulah High School Valley 36854 010055 Alexandria High School Alexandria 36250 010630 Bibb County High School Centreville 35042 010060 Aliceville High School Aliceville 35442 012114 Bible Methodist Christian Sch Pell City 35125 012625 Amelia L Johnson High School Thomaston 36783 012204 Bible Missionary Academy Pleasant 35127 -

Ahsaa Football Schedules, 2020 Class 4A Football Schedules

AHSAA FOOTBALL SCHEDULES, 2020 CLASS 4A FOOTBALL SCHEDULES ESCAMBIA COUNTY HIGH SCHOOL (CLASS 4A) Blue Devils (Region 1) DATE TIME OPPONENT SITE CLASS REG TYPE Aug-21-2020 7:00 PM Bayside Academy Home 3A REG 1 Aug-28-2020 7:00 PM T.R. Miller HS Home 3A REG 1 Sep-04-2020 7:00 PM Mobile Christian School Home 4A REG 1 REG Sep-11-2020 OPEN Sep-17-2020 7:00 PM St. Michael Catholic HS Away 4A REG 1 REG Sep-25-2020 7:00 PM Monroe County HS Home 3A REG 3 Oct-02-2020 7:00 PM Vigor HS Away 4A REG 1 REG Oct-09-2020 7:00 PM Williamson HS Home 4A REG 1 REG Oct-16-2020 7:00 PM W.S. Neal HS Away 4A REG 1 REG Oct-23-2020 7:00 PM Jackson HS Home 4A REG 1 REG Oct-30-2020 7:00 PM Flomaton HS Away 3A REG 1 JACKSON HIGH SCHOOL (CLASS 4A) Aggies (Region 1) DATE TIME OPPONENT SITE CLASS REG TYPE Aug-21-2020 7:00 PM T.R. Miller HS Away 3A REG 1 Aug-27-2020 7:00 PM Clarke County HS Home 3A REG 2 Sep-04-2020 7:00 PM St. Michael Catholic HS Home 4A REG 1 REG Sep-11-2020 7:00 PM Vigor HS Home 4A REG 1 REG Sep-18-2020 7:00 PM Selma HS Away 5A REG 3 Sep-25-2020 7:00 PM Thomasville HS Away 3A REG 3 Oct-02-2020 7:00 PM Williamson HS Away 4A REG 1 REG Oct-09-2020 7:00 PM W.S. -

Mobile, Alabama

“Choosing Education as a Career” Seminar: Mobile, Alabama In an effort to recruit more racially/ethnically diverse candidates, the COE held a national diverse student recruitment seminar in Mobile, Alabama, on June 7 – 8, 2018, titled “Choosing Education as a Career.” Invitations were extended to middle and high school principals, counselors, and parents in schools across Alabama, Mississippi, Florida, Georgia, South Carolina, Arkansas, and Kentucky. Thirty-seven individuals from six states attended the seminar and learned from MSU COE personnel about admissions, multicultural leadership scholarships, and year-long internship opportunities. The goal was to form partnerships with schools to recruit middle and high school students from underrepresented groups to choose teaching as a career. Some of these schools are now exploring options for working with the MSU EPP. Follow-up will be conducted in the late fall 2018 / early spring 2019 to determine how many students from the schools represented may be choosing education as a career as a result of this effort. INVITATION To: Personalize before sending. From: David Hough, Dean, College of Education, Missouri State Univesity Date: January 12, 2018 / January 16 / January 17 / January 18 / etc. Re: Seminar on Choosing Education as a Career You are invited to attend a Seminar to learn how high school sophomores and juniors can begin planning for a career in education. The Seminar will begin with a reception at 5:00 p.m. followed by a dinner meeting at 6:00 p.m. on Thursday, June 7, 2018. On Friday, June 8, 2018, sessions will begin at 9:00 a.m. -

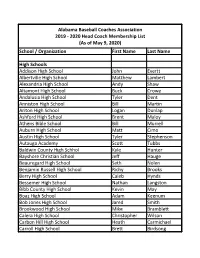

ALABCA Head Coach (WEB SITE) Member List at of May 9, 2020.Xltx

Alabama Baseball Coaches Association 2019 - 2020 Head Coach Membership List (As of May 9, 2020) School / Organization First Name Last Name High Schools Addison High School John Evertt Albertville High School Matthew Lambert Alexandria High School Andy Shaw Altamont High School Buck Crowe Andalusia High School Tyler Dent Anniston High School Bill Martin Ariton High School Logan Dunlap Ashford High School Brent Maloy Athens Bible School Bill Murrell Auburn High School Matt Cimo Austin High School Tyler Stephenson Autauga Academy Scott Tubbs Baldwin County High Schhol Kyle Hunter Bayshore Christian School Jeff Hauge Beauregard High School Seth Nolen Benjamin Russell High School Richy Brooks Berry High School Caleb Hynds Bessemer High School Nathan Langston Bibb County High School Kevin May Boaz High School Adam Keenum Bob Jones High School Jared Smith Brookwood High School Mike Bramblett Calera High School Christopher Wilson Carbon Hill High School Heath Carmichael Carroll High School Brett Birdsong Page 2 - School / Organization First Name Last Name Center Point High School Davion Singleton Central High School AJ Kehoe Chelsea High School Michael Stallings Childersburg High School Josh Podoris Chilton County High School Ryan Ellison Choctaw County High School Gary Banks Citronelle High School JD Phillips Clements High School Brody Gibson Collinsville High School Shane Stewart Cordova High School Lytle Howell Cullman High School Brent Patterson Curry High School Jeffrey Dean Dadeville High School Curtis Sharpe Dale County High School Patrick -

SSI I: Biobridge 2021 for 9Th Grade GEAR-UP Jefferson County Students

SSI I: BioBridge 2021 for 9th Grade GEAR-UP Jefferson County Students To be eligible for participation, applicants should: ▪ Currently be entering 9th grade attending a *GEAR UP Jefferson County School. ▪ Have an interest in and a demonstrated aptitude for science. ▪ Commit to being present on all days of the session. ▪ Submit a COMPLETED APPLICATION PACKET which includes: 1. The following Application Form 2. A current high school transcript 3. A letter of recommendation from a science teacher Deadline for Applications: May 21, 2021 by 5:00 pm Completed applications must be emailed to [email protected] UAB-CORD SUMMER SCIENCE INSTITUTE I BioBridge 2021 APPLICATION Requested session to attend (please check one): June 21-25________ July 26-30________ Contact Information: Applicant Name Date of Birth Mailing Address ____ City State Zip Code Telephone Number (Home) (Cell) Email Race M/F Name of Parent(s)/Guardian Mailing Address (if different) City State Zip Code Phone (Daytime) (Cell) Academic Information: 1. School that you will attend next fall and the grade you will enter: School District: 2. Scholastic awards or honors received: *Students entering 9th grade in the following schools receive a Gear Up scholarship for the entire tuition. Please check if you plan to attend one of the following schools, in the fall, below: Bessemer City High Fairfield High Prep Midfield High School Tarrant High School Clay-Chalkville High Center Point High School Fultondale High School Hueytown High School Shades Valley High McAdory High School Minor High School Pleasant Grove High Pinson Valley High I certify that the information contained in this application is correct and complete for participation in the SSI BioBridge program held at UAB-CORD June 21-25 OR July 26-30 from 9am to 3pm daily. -

Secondary School/ Community College Code List 2014–15

Secondary School/ Community College Code List 2014–15 The numbers in this code list are used by both the College Board® and ACT® connect to college successTM www.collegeboard.com Alabama - United States Code School Name & Address Alabama 010000 ABBEVILLE HIGH SCHOOL, 411 GRABALL CUTOFF, ABBEVILLE AL 36310-2073 010001 ABBEVILLE CHRISTIAN ACADEMY, PO BOX 9, ABBEVILLE AL 36310-0009 010040 WOODLAND WEST CHRISTIAN SCHOOL, 3717 OLD JASPER HWY, PO BOX 190, ADAMSVILLE AL 35005 010375 MINOR HIGH SCHOOL, 2285 MINOR PKWY, ADAMSVILLE AL 35005-2532 010010 ADDISON HIGH SCHOOL, 151 SCHOOL DRIVE, PO BOX 240, ADDISON AL 35540 010017 AKRON COMMUNITY SCHOOL EAST, PO BOX 38, AKRON AL 35441-0038 010022 KINGWOOD CHRISTIAN SCHOOL, 1351 ROYALTY DR, ALABASTER AL 35007-3035 010026 EVANGEL CHRISTIAN SCHOOL, PO BOX 1670, ALABASTER AL 35007-2066 010028 EVANGEL CLASSICAL CHRISTIAN, 423 THOMPSON RD, ALABASTER AL 35007-2066 012485 THOMPSON HIGH SCHOOL, 100 WARRIOR DR, ALABASTER AL 35007-8700 010025 ALBERTVILLE HIGH SCHOOL, 402 EAST MCCORD AVE, ALBERTVILLE AL 35950 010027 ASBURY HIGH SCHOOL, 1990 ASBURY RD, ALBERTVILLE AL 35951-6040 010030 MARSHALL CHRISTIAN ACADEMY, 1631 BRASHERS CHAPEL RD, ALBERTVILLE AL 35951-3511 010035 BENJAMIN RUSSELL HIGH SCHOOL, 225 HEARD BLVD, ALEXANDER CITY AL 35011-2702 010047 LAUREL HIGH SCHOOL, LAUREL STREET, ALEXANDER CITY AL 35010 010051 VICTORY BAPTIST ACADEMY, 210 SOUTH ROAD, ALEXANDER CITY AL 35010 010055 ALEXANDRIA HIGH SCHOOL, PO BOX 180, ALEXANDRIA AL 36250-0180 010060 ALICEVILLE HIGH SCHOOL, 417 3RD STREET SE, ALICEVILLE AL 35442 -

Past Award Recipients

ASAHPERD Award Recipients 1953 – 2020 Honor Award 2002 Linda Hatchett, O’Rourke Elementary School 1953 H.A. Flowers, Florence State College 2003 No award Jessie G. Mehling, Alabama Department of Education 2004 Carolyn Sapp Bishop, retired, Tuscaloosa City Schools Jackson R. Sharman, University of Alabama 2005 Willie Hey, Jacksonville State University Ethel J. Saxman, University of Alabama Donald Staffo, Stillman College 1954 William Battle, Birmingham Southern College 2006 Allison Jackson, Samford University Jeanetta T. Land, Auburn University 2007 Connie Dacus, Alabama State University Margaret McCall, Alabama College Sherri Huff, Birmingham City Schools 1955 Louise Temerson, University of Alabama Diane Shelton, Hartselle Jr. High 1956 Jimmie H. Goodman, Shades Valley High School, Birmingham 2008 Emily Pharez, L. Newton School, Fairhope Vernon W. Lapp, Auburn University Steve Pugh, University of South Alabama Louise F. Turner, Auburn University Charles D. Sands, Samford University 1958 Cliff Harper, AL High School Athletic Association 2009 Benny Eaves, Mountain Brook High School Willis Baughman, University of Alabama Kay Hamilton, Alabama A&M University 1959 Bernice Finger, Alabama College 2010 Suzanne Stone, Morris Elementary, Huntsville 1960 Harriet Donahoo, Auburn University Hank Williford, Auburn Montgomery 1961 Geneva Myrick, Alabama College 2011 Brian Geiger, University of Alabama at Birmingham 1965 Blondie Crawford, Cullman Co. Board of Education James Angel, Samford University Minnie Sellers, Tuscaloosa Recreation Department -

Public Schools in The

Case 2:65-cv-00396-MHH Document 1141 Filed 04/24/17 Page 1 of 190 FILED 2017 Apr-24 PM 05:13 U.S. DISTRICT COURT N.D. OF ALABAMA UNITED STATES DISTRICT COURT FOR THE NORTHERN DISTRICT OF ALABAMA SOUTHERN DIVISION LINDA STOUT, et al., ) ) Plaintiffs, ) ) UNITED STATES OF AMERICA, ) ) Plaintiff-Intervenor, ) ) v. ) Case No.: 2:65-cv-00396-MHH ) JEFFERSON COUNTY BOARD OF ) EDUCATION, ) ) Defendant, ) ) GARDENDALE CITY BOARD OF ) EDUCATION, ) ) Defendant-Intervenor. ) MEMORANDUM OPINION AND ORDER “[T]he future of our world revolves around public education. There’s nothing more important that we do” than “educat[ing] our children.” (Doc. 1124, p, 180). That proposition, offered by a member of the Gardendale Board of Education, is perhaps the one point on which all of the parties in this school desegregation case agree. The proposition is sound. In its landmark decision in Brown v. Board of Education, the United States Supreme Court recognized that 1 Case 2:65-cv-00396-MHH Document 1141 Filed 04/24/17 Page 2 of 190 public education is critical for the welfare of our nation’s children. The Supreme Court stated that public education: is the very foundation of good citizenship. Today it is a principal instrument in awakening the child to cultural values, in preparing him for later professional training, and in helping him to adjust normally to his environment. In these days, it is doubtful that any child may reasonably be expected to succeed in life if he is denied the opportunity of an education. 347 U.S. 483, 493 (1954). -

X‐Indicates Schools Not Participating in Football.

(x‐Indicates schools not participating in football.) Hoover High School 1,902.95 Sparkman High School 1,833.70 Baker High School 1,622.25 Murphy High School 1,601.00 Prattville High School 1,516.15 Bob Jones High School 1,491.35 Enterprise High School 1,482.50 Virgil Grissom High School 1,467.05 Auburn High School 1,445.95 Jeff Davis High School 1,442.60 Smiths Station High School 1,358.00 Vestavia Hills High School 1,355.25 Thompson High School 1,319.70 Mary G. Montgomery High School 1,316.60 Huntsville High School 1,296.70 Central High School, Phenix City 1,267.35 Pelham High School 1,259.30 R. E. Lee High School 1,258.65 Oak Mountain High School 1,258.05 Theodore High School 1,228.60 Alma Bryant High School 1,168.65 Foley High School 1,145.80 McGill‐Toolen High School 1,131.30 Spain Park High School 1,128.10 Tuscaloosa County High School 1,117.35 Gadsden City High School 1,085.65 W.P. Davidson High School 1,056.35 Mountain Brook High School 1,009.15 Shades Valley High School 1,006.15 Northview High School 1,002.35 Fairhope High School 994.80 Hewitt‐Trussville High School 991.00 Austin High School 976.75 Hazel Green High School 976.50 Clay‐Chalkville High School 965.55 Florence High School 960.30 Pell City High School 924.45 G. W. Carver High School, Montgomery 918.80 Opelika High School 910.55 Buckhorn High School 906.25 Northridge High School 901.25 Lee High School, Huntsville 885.85 Oxford High School 883.75 Stanhope Elmore High School 880.70 Hillcrest High School 875.40 Robertsdale High School 871.05 Mattie T.