Rpsgroup.Com/London FOLKSTONE RACECOURSE, WESTENHANGER

Total Page:16

File Type:pdf, Size:1020Kb

Load more

Recommended publications

-

Inscribed 6 (2).Pdf

Inscribed6 CONTENTS 1 1. AVIATION 33 2. MILITARY 59 3. NAVAL 67 4. ROYALTY, POLITICIANS, AND OTHER PUBLIC FIGURES 180 5. SCIENCE AND TECHNOLOGY 195 6. HIGH LATITUDES, INCLUDING THE POLES 206 7. MOUNTAINEERING 211 8. SPACE EXPLORATION 214 9. GENERAL TRAVEL SECTION 1. AVIATION including books from the libraries of Douglas Bader and “Laddie” Lucas. 1. [AITKEN (Group Captain Sir Max)]. LARIOS (Captain José, Duke of Lerma). Combat over Spain. Memoirs of a Nationalist Fighter Pilot 1936–1939. Portrait frontispiece, illustrations. First edition. 8vo., cloth, pictorial dust jacket. London, Neville Spearman. nd (1966). £80 A presentation copy, inscribed on the half title page ‘To Group Captain Sir Max AitkenDFC. DSO. Let us pray that the high ideals we fought for, with such fervent enthusiasm and sacrifice, may never be allowed to perish or be forgotten. With my warmest regards. Pepito Lerma. May 1968’. From the dust jacket: ‘“Combat over Spain” is one of the few first-hand accounts of the Spanish Civil War, and is the only one published in England to be written from the Nationalist point of view’. Lerma was a bomber and fighter pilot for the duration of the war, flying 278 missions. Aitken, the son of Lord Beaverbrook, joined the RAFVR in 1935, and flew Blenheims and Hurricanes, shooting down 14 enemy aircraft. Dust jacket just creased at the head and tail of the spine. A formidable Vic formation – Bader, Deere, Malan. 2. [BADER (Group Captain Douglas)]. DEERE (Group Captain Alan C.) DOWDING Air Chief Marshal, Lord), foreword. Nine Lives. Portrait frontispiece, illustrations. First edition. -

3 Ivydene Stone Street Westenhanger CT21 4HS Guide £259,950 EPC Rating: D

3 Ivydene Stone Street Westenhanger CT21 4HS Guide £259,950 EPC Rating: D 3 Ivydene Stone Street Westenhanger Kent CT21 4HS A pretty two bedroom cottage close to commuting services. No Chain. Situation A pretty two bedroom country cottage in a sought The property benefits from some double glazing after location within the popular hamlet of and oil fired central heating. Westenhanger, only moments from Westenhanger mainline railway station which connects to the Outside High Speed rail link to St Pancras. Local amenities can be found in the neighbouring The property is approached by a side pathway village of Lympne, and Hythe’s busy high street leading to the front door and the long lawned rear with a variety of independent shops, restaurants garden, provides a secure and private and four supermarkets is nearby. environment in which to relax and entertain. Commuting services are excellent with High There are two outbuildings, one currently used as Speed transport links to London St Pancras via a utility area and the other may offer the Westenhanger station, Sandling and Folkestone opportunity for those wanting a workshop or a West in little under an hour. studio. The M20 motorway nearby provides a network to There is off street parking to the front and side the remainder of Kent and Eurotunnel in Cheriton vehicle access (by private arrangement) with offers connections to the Continent. parking for several vehicles, The Property Services We understand all main services are available A charming two bedroom end of terrace period except gas. Oil fired central heating. cottage standing in generous gardens with off road parking. -

Sellindge Village News July 2016

SELLINDGE VILLAGE NEWS JULY 2016 Edition 627 SELLINDGE VILLAGE HALL TABLE TOP FAIR Registered Charity 302833 th Saturday July 4 2016 from 9am to 1pm. Tables can be booked in advance for £5.00 per table. Please phone 01303 813 475 or on the day, if any left at £10. Next Table Top Fair Saturday August 6th 2016. AFTERNOON BOOT FAIR Saturday July 9th at the Sports and Social Club in Swan Lane -- £5 per pitch – starts 11am. (Weather permitting). WHAT A BUSY JUNE OTTERPOOL PARK / STANFORD LORRY HOLDING AREA PROTEST MARCH It all started on the afternoon of Saturday June 4th where villagers from Sellindge, Lympne, Monks Horton and Stanford, went on a Protest March, against the decision of Shepway District Council to express an interest for the Government’s Garden Town initiative. If successful then Otterpool Park Garden Town with 12,000 homes could be built on land between Sellindge, Lympne and Stanford. The Protesters left the Village Hall at around 2pm, and made their way up Barrow Hill towards the Airport Café. At the same time another group of protesters set of from Newingreen towards the Airport Café. Once both Protest Marches reached the Airport Café a rally was held with various speakers addressed the crowd of between 300 and 400 protesters. CELEBRATION OF THE QUEENS 90th BIRTHDAY THE KINGS AND QUEENS CAR PARK PARTY The following Saturday June 11th, there was a party atmosphere at the Village Hall, when more than 140 Sellindge residents attended the Kings and Queens Car Park party. Starting off with a grand tea party on the car park, with live music by the group ‘Southern Dawn’. -

The Folkestone School for Girls

Buses serving Folkestone School for Girls page 1 of 6 via Romney Marsh and Palmarsh During the day buses run every 20 minutes between Sandgate Hill and New Romney, continuing every hour to Lydd-on-Sea and Lydd. Getting to school 102 105 16A 102 Going from school 102 Lydd, Church 0702 Sandgate Hill, opp. Coolinge Lane 1557 Lydd-on-Sea, Pilot Inn 0711 Hythe, Red Lion Square 1618 Greatstone, Jolly Fisherman 0719 Hythe, Palmarsh Avenue 1623 New Romney, Light Railway Station 0719 0724 0734 Dymchurch, Burmarsh Turning 1628 St Mary’s Bay, Jefferstone Lane 0728 0733 0743 Dymchurch, High Street 1632 Dymchurch, High Street 0733 0738 0748 St. Mary’s Bay, Jefferstone Lane 1638 Dymchurch, Burmarsh Turning 0736 0741 0751 New Romney, Light Railway Station 1646 Hythe, Palmarsh Avenue 0743 0749 0758 Greatstone, Jolly Fisherman 1651 Hythe, Light Railway Station 0750 0756 0804 Lydd-on-Sea, Pilot Inn 1659 Hythe, Red Lion Square 0753 0759 0801 0809 Lydd, Church 1708 Sandgate Hill, Coolinge Lane 0806 C - 0823 Lydd, Camp 1710 Coolinge Lane (outside FSG) 0817 C - Change buses at Hythe, Red Lion Square to route 16A This timetable is correct from 27th October 2019. @StagecoachSE www.stagecoachbus.com Buses serving Folkestone School for Girls page 2 of 6 via Swingfield, Densole, Hawkinge During the daytime there are 5 buses every hour between Hawkinge and Folkestone Bus Station. Three buses per hour continue to Hythe via Sandgate Hill and there are buses every ten minutes from Folkestone Bus Station to Hythe via Sandgate Hill. Getting to school 19 19 16 19 16 Going -

Parish of Postling

PARISH OF POSTLING ANNUAL PARISH MEETING 2016 DRAFT Minutes of Postling Annual Parish Meeting held at Parish Village Hall on Wednesday 25 May 2016 starting at 7.30pm. PRESENT: Cllr Frank Hobbs (Chair), Cllr Christine Hobbs, Cllr John Elphick, Cllr Helen Calderbank, Jo Maher (Clerk), County District Councillor Susan Carey, KALC Chairman Ray Evison, Clive Adsett, Christine Webb, Tony Van Eldik, Marieke Van Eldik, Pat Elphick, Jan Wood, Derek Wood, Jenny Mannion 1) APOLOGIES: District Councillor Jenny Hollingsbee, Cllr John Pattrick, Cllr Charlie Wilkins, Cllr Jane Reynolds, Chris Reynolds, Gill Dixon 2) MINUTES OF THE PREVIOUS MEETING: The Minutes of the previous Annual Parish Meeting held on Wednesday 20 May 2015 were approved and signed by the Chair. This was proposed by Cllr Elphick, seconded by Cllr Christine Hobbs and unanimously agreed. 3) CHAIRMAN’s REPORT: Your Parish Council had another busy year. We are currently threatened by major developments in the area. The on-going consultation about the lorry park at Junction 11 was expected to report some time ago on the preferred site, but there is no news yet, and now probably won’t be released until after the referendum. This could have a knock-on effect on the sand extraction site if they chose Option 2. And now there is the proposal from Shepway DC for a “garden town” running on the southern side of the motorway from Junction 11 to the western edge of Sellindge, no doubt Cllr Carey will enlighten us more in her report. We have been invited to a meeting at SDC early next month, along with the other affected parishes, to be briefed fully on the proposed project. -

Some Problems of the North Downs Trackway in Kent

http://kentarchaeology.org.uk/research/archaeologia-cantiana/ Kent Archaeological Society is a registered charity number 223382 © 2017 Kent Archaeological Society SOME PROBLEMS OF THE NORTH DOWNS TRACKWAY IN KENT By REV. H. W. R. Liman, S.J., M.A.(0xon.) THE importance of this pre-historic route from the Continent to the ancient habitat of man in Wiltshire has long been recognized. In the Surrey Archceological Collections of 1964 will be found an attempted re-appraisal of its route through the county of Surrey. Although the problems connected with its passage through Kent are fewer owing to its being better preserved, there are some points which I think still deserve attention—the three river crossings of the Darenth, the Medway and the Stour; the crossing of the Elham valley; and the passage to Canterbury of the branch route from Eastwell Park, known as the Pilgrims' Way. It may be worth while, before dealing with the actual crossings, to note a few general characteristics. Mr. I. D. Margary—our most eminent authority on ancient roads in Britain—has pointed out the dual nature of this trackway. It com- prises a Ridgeway and a Terraceway. The first runs along the crest of the escarpment. The second runs parallel to it, usually at the point below the escarpment where the slope flattens out into cultivation. In Kent for the most part the Terraceway has survived more effectually than the Ridgeway. It is for much of its length used as a modern road, marked by the familiar sign 'Pilgrims' Way'. Except at its eastern terminus the Ridgeway has not been so lucky, although it can be traced fairly accurately by those who take the trouble to do so. -

0 Medieval Flokestone Robertson

http://kentarchaeology.org.uk/research/archaeologia-cantiana/ Kent Archaeological Society is a registered charity number 223382 © 2017 Kent Archaeological Society ( civ ) MEDIAEVAL FOLKESTONE. FOLKESTONE gives its name to one of the Hundreds of Kent, and was the site of a nunnery (said to have been the first in England), founded in the seventh century by Eadbald, King of Kent, the father of St. Eanswith, its first Abbess. These facts prove that the town was in earlier times a place of some importance, but very little is known respecting its history, prior to the Middle Ages. It is evident that the name, spelt Polcstane in the earlier records, was given by the Saxons,* and that it was derived from the natural peculiarities of the place, its stone quarries having always played a conspicuous part in its history. They are mentioned in two extents (or valuations) of the manor of " Folcstane" which were made in the reign, of Henry III. In the first of these, dated 1263, we read that "there are there certain quarries worth per annum-)- 20s." The second gives us further information; it is dated 1271, and says "the quarry J in which mill-stones and handmill- stones are dug " is worth 20s. per annum. Such peaceful and useful implements as mill-stones were, however, by no means the only produce of these quarries. When Edward III., and his son the Black Prince, were prosecuting their conquests in France, some of the implements of war were obtained from Folkestone. On Jan. the 9th, 1356,§ the King ordered the Warden of the Cinque Ports to send over to Calais|| those stones for warlike engines which had been prepared at Folkestone. -

(Public Pack)Agenda Document for Governance Committee, 13/07

Despatched: 03.07.15 GOVERNANCE COMMITTEE 13 July 2015 at 6.00 pm Conference Room, Argyle Road, Sevenoaks AGENDA Membership : Chairman: Cllr. Pett Vice -Chairman: Cllr. Ms. Tennessee Cllrs. Dr. Canet, Clack, Halford, Layland and London Pages Contact Apologies for Absence 1. Minutes (Pages 1 - 4) To agree the Minutes of the meeting of the Committee held on 26 February 2015 as a correct record. 2. Declarations of Interest Any interest not already registered 3. Actions arising from the last meeting (if any) 4. Overview of Governance Committee (Pages 5 - 8) Christine Nuttall Tel: 01732 227245 5. The Local Authorities (Standing (Pages 9 - 20) Christine Nuttall Orders)(England)(Amendment) Regulations 2015 - Tel: 01732 227245 Appointment and Dismissal of Senior Officers 6. KCC Boundary Review - Response to Consultation (Pages 21 - 92) Christine Nuttall Tel: 01732 227245 7. Work Plan (Pages 93 - 94) EXEMPT ITEMS (At the time of preparing this agenda there were no exempt items. During any such items which may arise the meeting is likely NOT to be open to the public.) To assist in the speedy and efficient despatch of business, Members wishing to obtain factual information on items included on the Agenda are asked to enquire of the appropriate Contact Officer named on a report prior to the day of the meeting. Should you require a copy of this agenda or any of the reports listed on it in another format please do not hesitate to contact the Democratic Services Team as set out below. For any other queries concerning this agenda or the meeting please contact: The Democratic Services Team (01732 227241) Agenda Item 1 GOVERNANCE COMMITTEE Minutes of the meeting held on 26 February 2015 commencing at 7.00 pm Present : Cllr. -

M20 Junction

M20 Junction 10a TR010006 5.1 Consultation Report APFP Regulation 5(2)(q) Revision A Planning Act 2008 Infrastructure Planning (Applications: Prescribed Forms and Procedure) Regulations 2009 Volume 5 July 2016 M20 Junction 10a TR010006 5.1 Consultation Report Volume 5 This document is issued for the party which commissioned it We accept no responsibility for the consequences of this and for specific purposes connected with the above-captioned document being relied upon by any other party, or being used project only. It should not be relied upon by any other party or for any other purpose, or containing any error or omission used for any other purpose. which is due to an error or omission in data supplied to us by other parties This document contains confidential information and proprietary intellectual property. It should not be shown to other parties without consent from us and from the party which commissioned it. Date: July 2016 M20 Junction 10a Consultation Report TR010006 Foreword Highways England has undertaken a fully managed programme of consultation with the local community and wider stakeholders. The consultation process has facilitated feedback which has been carefully considered throughout the development of the M20 junction 10a Scheme (the 'Scheme'). Pre-application consultation is an important element of any Nationally Significant Infrastructure Project. Highways England has taken careful consideration to relevant legislation, guidance and notes when designing the pre-application strategy. Early consultation addressed the main strategic and audience interaction needs to deliver a meaningful and progressive engagement programme. A number of different model groups were supported throughout the non-statutory engagement period. -

Appendix 1 Proposed List of Allocation Sites (Work in Progress)

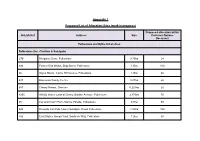

Appendix 1 Proposed List of Allocation Sites (work in progress) Proposed allocation within SHLAA Ref Address Size Preferred Options Document Folkestone and Hythe Urban Area Folkestone (inc. Cheriton & Sandgate) 27B Shepway Close, Folkestone 0.79ha 24 346 Former Gas Works, Ship Street, Folkestone 1.5ha 100 46 Ingles Manor, Castle Hill Avenue, Folkestone 1.9ha 46 637 Brockman Family Centre 0.87ha 26 687 Cherry Pickers, Cheriton 0.223ha 20 425C Affinity Water, Land at Cherry Garden Avenue, Folkestone 2.875ha 70 45 Car and Coach Park, Marine Parade, Folkestone 0.7ha 65 342 Rotunda Car Park, Lower Sandgate Road, Folkestone 1.02ha 100 382 East Station Goods Yard, Southern Way, Folkestone 1.2ha 68 458 Highview School, Moat Farm Road, Folkestone 0.9ha 27 113 Former Encombe House, Sandgate 1.6ha 36 636 Shepway Resource Centre, Sandgate 0.64ha 41 103 Royal Victoria Hospital, Radnor Park Avenue, Folkestone 1ha 42 625 3-5 Shorncliffe Road, Folkestone 0.15ha 20 405 Coolinge Lane Land, Folkestone 4.54ha 40 Hythe 137 Smiths Medical, Boundary Road, Hythe 3.2ha 80 142 Hythe Pool, South Road, Hythe 0.5ha 50 621 Land opposite 24 Station Road, Hythe 1.25ha 40 313 Foxwood School, Seabrook Road, Hythe 6.3ha 150 153 Princes Parade, Hythe 7.2ha 150 1018 St Saviour's Hospital, Hythe 1.15ha 35 622 Saltwood Care Centre, Tanners Hill, Hythe 2ha TBC North Downs Hawkinge 244 Former Officers Mess, Aerodrome Road, Hawkinge 3.75ha 70 334 Mill Lane r/o Mill Farm, Hawkinge 1.1ha 14 404 Land adj Kent Battle of Britain Museum, Aerodrome Road, Hawkinge 5.5ha 100 Sellindge -

Investigations and Excavations During the Year

http://kentarchaeology.org.uk/research/archaeologia-cantiana/ Kent Archaeological Society is a registered charity number 223382 © 2017 Kent Archaeological Society INVESTIGATIONS AND EXCAVATIONS DURING THE YEAR I. REPORTS ON EXCAVATIONS SUPPORTED BY THE SOCIETY Interim Report by Mr. P. J. Tester, F.S.A., on, the Excavations at Boxley Abbey. By the courtesy of our member, Sir John Best-Shaw, the Kent Archmological Society has conducted excavations during 1971 at Boxley Abbey for the purpose of determining the monastic layout. Five members of the Excavations Committee have taken an active part in the investigation and assistance has been given by the Archaeo- logical Society of Sir Joseph Williamson's Mathematical School, the Lower Medway Archwological Research Group and the Maidstone Area Archmological Group. A preliminary site-plan was prepared by Mr. J. E. L. Caiger who also conducted a resistivity survey. Excavation has consisted mainly of cross-trenching to locate buried footings, and by this means considerable additions have been made to our knowledge of the plan. In general, the arrangement as shown in the late F. C. Elliston- Erwood's plan in Arch. Cant., lxvi (1953) has been proved to be substantially correct, with several qualifications. The church was of the same form and dimensions as he showed except that the transepts were longer (north-south) and contained three eastern chapels each instead of two. Some walls discovered in a small excavation by Mr. B. J. Wilson in 1959 and 1966 are now seen to be related to the night-stair in the south-west corner of the south transept. -

COUNTRYSIDE Page 1 of 16

Page 1 of 16 COUNTRYSIDE Introduction 12.1 Shepway has a rich and diverse landscape ranging from the rolling chalk downland and dry valleys of the North Downs, through the scarp and dip slope of the Old Romney Shoreline, to Romney Marsh and the unique shingle feature of the Dungeness peninsula. This diversity is reflected in the range of Natural Areas and Countryside Character Areas, identified by English Nature and the Countryside Agency respectively, which cover the District. The particular landscape and wildlife value of large parts of the District is also recognised through protective countryside designations, including Sites of Special Scientific Interest and Heritage Coastline, as well as the Kent Downs Area of Outstanding Natural Beauty. The countryside also plays host to a wide range of activities and it is recognised that the health of the rural economy and the health of the countryside are inter-linked. A function of the Local Plan is to achieve a sustainable pattern of development in the countryside. This involves a balance between the needs of rural land users and maintaining and enhancing countryside character and quality. 12.2 This balance is achieved in two main ways:- a. By focussing most development in urban areas, particularly on previously developed sites and ensuring that sufficient land is allocated to meet identified development requirements, thus reducing uncertainty and speculation on ‘greenfield’ sites in the countryside. b. By making firm policy statements relating to: the general principles to be applied to all proposals in the countryside; specific types of development in the countryside; and the protection of particularly important areas.