Xviii Predicting, Prophecying, Divining And

Total Page:16

File Type:pdf, Size:1020Kb

Load more

Recommended publications

-

Treatise on Astral Projection V2

TREATISE ON ASTRAL PROJECTION V2 by Robert Bruce Copyright © 1999 Contents Part One................................................................................................................................. 1 Part Two................................................................................................................................. 6 Part Three .............................................................................................................................. 12 Part Four ............................................................................................................................... 17 Part Five ................................................................................................................................ 21 Part Six................................................................................................................................... 27 Part Seven .............................................................................................................................. 34 Part Eight............................................................................................................................... 41 Book Release – “Astral Dynamics”....................................................................................... 51 Book Release – “Practical Psychic Self-Defense”................................................................ 52 i Copyright © Robert Bruce 1999 1 Part One This version has been completely rewritten and updated, with thought to all -

Occult Worksheet

OCCULT WORKSHEET Participating in any of these activities does not automatically mean that demonic inroads are opened into a person’s life, but these activities can open a person and make them vulnerable. Occult games or activities Magic -- black or white Attend a séance or spiritualist meeting Attend or participate in Wicca (white witch) Participated in astrology by: activities or church read or follow horoscopes Attend or participate in witchcraft or voodoo astrology chart made for self Learned how to cast a magic spell Party games involved with: Practice magic (use of true supernatural automatic writing powers) clairsentience (through touch) Place, sent or spoken a curse against clairvoyance / mind reading someone crystal ball gazing Participated in chain letter where there was a ESP (Extra Sensory Perception) curse against those who did not participate healing magnetism Used a charm of any kind for protection hypnotism Participated in or entered into a blood pact or levitation (lifting bodies) covenant magic eight ball Sought healing though: mental suggestion magic spells mental telepathy charms Ouija Board Christian Scientist reader palm reading spiritualist perceiving auras witch doctor precognition shaman psychometry Practiced water witching or dowsing self hypnosis Predict sex of unborn child with divining rod speaking in a trance Read or possess books about magic, magic table tipping / lifting spells, or witchcraft tarot cards Played Dungeons and Dragons using spells telekinesis / parakinesis (move objects with -

Rezension Über: Owen Davies, a Supernatural War. Magic

Zitierhinweis Miller, Ian: Rezension über: Owen Davies, A Supernatural War. Magic, Divination, and Faith during the First World War, Oxford: Oxford University Press, 2019, in: Reviews in History, 2019, May, DOI: 10.14296/RiH/2014/2318, heruntergeladen über recensio.net First published: https://reviews.history.ac.uk/review/2318 copyright Dieser Beitrag kann vom Nutzer zu eigenen nicht-kommerziellen Zwecken heruntergeladen und/oder ausgedruckt werden. Darüber hinaus gehende Nutzungen sind ohne weitere Genehmigung der Rechteinhaber nur im Rahmen der gesetzlichen Schrankenbestimmungen (§§ 44a-63a UrhG) zulässig. Historically, wars have always witnessed reports of ghostly sightings and visions. However, the First World War is of particular interest as such phenomena occurred in a more modern, secular environment, at a time when science and secularisation had emerged as predominant ways of thinking about the world. In addition, the number of lives being lost due to conflict was unprecedented. However, the work of groups such as the Society for Psychical Research aside, secular scientific thought did not easily accommodate the idea of a world beyond our own populated by the departed. Nor did it entertain amulets, charms, astrology or belief in luck. Science had now relegated these to superstition and folklore. Owen Davies’ A Supernatural War: Magic, Divination and Faith during the First World War provides a compelling overview of (what might be termed) a ‘hidden history’ of the First World War, one that reveals European societies still enthralled by the supernatural even in the context of modern, technologised conflict. A Supernatural War commences with a discussion of how sociologists, psychologists and anthropologists considered the battlefields of French and Belgium to be a unique laboratory for research. -

![The Compleat Works of Nostradamus -=][ Compiled and Entered in PDF Format by Arcanaeum: 2003 ][=](https://docslib.b-cdn.net/cover/3323/the-compleat-works-of-nostradamus-compiled-and-entered-in-pdf-format-by-arcanaeum-2003-2343323.webp)

The Compleat Works of Nostradamus -=][ Compiled and Entered in PDF Format by Arcanaeum: 2003 ][=

The Compleat Works of Nostradamus -=][ compiled and entered in PDF format by Arcanaeum: 2003 ][=- Table of Contents: Preface Century I Century II Century III Century IV Century V Century VI Century VII Century VIII Century IX Century X Epistle To King Henry II Pour les ans Courans en ce Siecle (roughly translated: for the years’ events in this century) Almanacs: 1555−1563 Note: Many of these are written in French with the English Translation directly beneath them. Preface by: M. Nostradamus to his Prophecies Greetings and happiness to César Nostradamus my son Your late arrival, César Nostredame, my son, has made me spend much time in constant nightly reflection so that I could communicate with you by letter and leave you this reminder, after my death, for the benefit of all men, of which the divine spirit has vouchsafed me to know by means of astronomy. And since it was the Almighty's will that you were not born here in this region [Provence] and I do not want to talk of years to come but of the months during which you will struggle to grasp and understand the work I shall be compelled to leave you after my death: assuming that it will not be possible for me to leave you such [clearer] writing as may be destroyed through the injustice of the age [1555]. The key to the hidden prediction which you will inherit will be locked inside my heart. Also bear in mind that the events here described have not yet come to pass, and that all is ruled and governed by the power of Almighty God, inspiring us not by bacchic frenzy nor by enchantments but by astronomical assurances: predictions have been made through the inspiration of divine will alone and the spirit of prophecy in particular. -

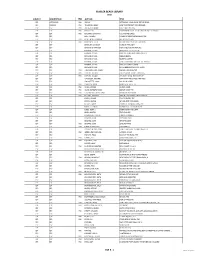

Flagler Beach Library Esp P. 1

FLAGLER BEACH LIBRARY 2015 SUBJECT DESCRIPTION TYPE AUTHOR TITLE ESP ASTROLOGY PBK ZODIAC ASTROLOGY: YOUR GUIDE TO THE STARS ESP DREAMS PBK THURSTON, MARK HOW TO INTERPRET YOUR DREAMS ESP ESP PBK ALTEA, ROSEMARY EAGLE AND THE ROSE ESP ESP PBK BADER, LOIS COMPANION GUIDE TO THE ONLY PLANET OF CHOICE ESP ESP PBK BALDWIN, CHRISTINA CALLING THE CIRCLE ESP ESP BALL, PAMELA POWER OF CREATIVE THINKING. THE ESP ESP PBK BOYER & NISSENBAUM SALEM POSSESSED ESP ESP PBK BRADY & ST. LIFER DISCOVERING YOUR SOUL MISSION ESP ESP BRINKLEY, DANNION SAVED BY THE LIGHT ESP ESP BROWNE & HARRISON PAST LIVES, FUTURE HEALING ESP ESP BROWNE, SYLVIA ADVENTURES OF A PSYCHIC ESP ESP BROWNE, SYLVIA GOD, CREATION AND TOOLS FOR LIFE ESP ESP BROWNE, SYLVIA PHENOMENON ESP ESP BROWNE, SYLVIA SECRET SOCIETIES ESP ESP BROWNE, SYLVIA SECRETS AND MYSTERIES OF THE WORLD ESP ESP BROWNE, SYLVIA SPIRITUAL CONNECTIONS ESP ESP BROWNE, SYLVIA SYLVIA BROWN'S BOOK OF ANGEL ESP ESP PBK CALLEMAN, CARL JOHAN MAYAN CALENDAR, THE ESP ESP PBK CAPUTO, THERESA THERE'S MORE TO LIFE THAN THIS ESP ESP PBK CAPUTO, THERESA YOU CAN'T MAKE THIS STUFF UP ESP ESP CAVENDISH, RICHARD MAN MYTH AND MAGIC PART TWO ESP ESP CHOQUETTE, SONIA ASK YOUR GUIDES ESP ESP PBK CIANCIOSI, JOHN MEDITATIVE PATH, THE ESP ESP PBK CLARK, JEROME UNEXPLAINED ESP ESP PBK CLOW, BARBARA HAND MAYAN CODE, THE ESP ESP PBK COOPER, MILTON WILLIAM BEHOLD A PALE HORSE ESP ESP PBK DELONG, DOUGLAS ANCIENT TEACHINGS FOR BEGINNERS ESP ESP DIXON, JEANNE CALL TO GLORY, THE ESP ESP DIXON, JEANNE MY LIFE AND PROPHECIES ESP ESP DOSSEY, LARRY POWER OF PREMONITIONS, THE ESP ESP DRUSE, ELEANOR JOURNALS OF ELEANOR DRUSE ESP ESP EADIE, BETTY J. -

Nostradamus the 21St Century and Beyond

Nostradamus The 21st Century and Beyond The present — which is still unfolding, is cloudy because we’re too close to that forest to see the trees as they emerge from the mists of time. But the thing all of us are most intrigued by is this: What does Nostradamus tell us about our own future —which, after all, is where we’ll be spending all our time? Is it to be all doom and gloom as some read into Nostradamus? Or were those frightening scenarios merely reflections of the prophet’s own gloomy character and the superstitious, medieval mind-set that produced him? Page 1 of 31 Nostradamus The 21st Century and Beyond Any discussion of Nostradamus’ predictions about our future has to deal to some extent with what appear to be doomsday forecasts and the coming of the third Antichrist. That is too much a part of the Nostradamus saga. But only a part. He also had a lot to say about the glorious, golden days that lie before us. However, the one prediction that preoccupies most Nostradamus scholars to the point of obsession — and chills some to the bone — is the one he recorded in CX Q72 which reads: ------------------------------------------------------------------------------ “In the year 1999, and seven months from the sky will come the great King of Terror. He will bring to life the great King of the Mongols. Before and after war reigns happily.” ---------------------------------------------------------------------------- Most experts have interpreted this famous quatrain as the prophet’s vision of an Antichrist. If Napoleon was the first and Hitler the second, the big questions obviously are: Who’s the third Antichrist? Is he/she/it among us today? Or still decades, even centuries, in the future? According to Christian legend, the Antichrist is a person or power that will come to corrupt the world but will then be conquered by Christ’s Second Coming. -

Edgar Cayce - the Sleeping Prophet by Jess Stearn

Edgar Cayce - The Sleeping Prophet By Jess Stearn Contents: Book Cover (Front) (Back) Scan / Edit Notes Quote 1 - The Sleeping Wonder 2 - Cayce The Man 3 - Cayce's Time Clock 4 - Checking Him Out 5 - California - earthquakes 6 - World Prophecies 7 - The Doctors And Cayce 8 - Twenty Years Later 9 - The Doctors Catch On 10 - The Incurable Diseases 11 - Cayce's Home Remedies 12 - The Dream World 13 - At Last, Atlantis 14 - Reincarnation 15 - The Cayce Babies 16 - The Reckoning Scan / Edit Notes Versions available and duly posted: Format: v1.0 (Text) Format: v1.0 (PDB - open format) Format: v1.5 (HTML) Format: v1.5 (PDF - no security) Format: v1.5 (PRC - for MobiPocket Reader - pictures included) Genera: Psychic Extra's: Pictures Included (for all versions) Copyright: 1968 / 1989 First Scanned: 2002 Posted to: alt.binaries.e-book Note: 1. The Html, Text and Pdb versions are bundled together in one zip file. 2. The Pdf and Prc files are sent as single zips (and naturally don't have the file structure below) ~~~~ Structure: (Folder and Sub Folders) {Main Folder} - HTML Files | |- {Nav} - Navigation Files | |- {PDB} | |- {Pic} - Graphic files | |- {Text} - Text File -Salmun Quote God is our refuge and strength, a very present help in trouble. Therefore will not we fear, though the earth be removed, and though the mountains be carried into the midst of the sea. Psalm 46 1 - The Sleeping Wonder It was like any other day for Edgar Cayce. He went to sleep, by merely lying down and closing his eyes, and then he started to talk in his sleep. -

“Unheard of Curiosities” an Exhibition of Rare Books on the Occult and Esoteric Sciences

“Unheard of Curiosities” An Exhibition of Rare Books on the Occult and Esoteric Sciences Exhibition Catalog by Erika B. Gorder February 2014 Special Collections and University Archives Rutgers University Libraries About the Exhibition “Unheard-of Curiosities”: An Exhibition of Rare Books on the Occult and Esoteric Sciences showcases rare books from Special Collections and University Archives that display evidence of the enduring popular interest in a diverse constellation of “occult” topics from the 16th century to the present day. The exhibition primarily features books collected by the late Rutgers Professor of English, Clement Fairweather (the "Fairweather Collection"), which predominantly center on astrology and early astronomy from the 17th through the 19th centuries. Secondary topics include prediction and prophecy, demons and the devil, witchcraft and magic, the mysteries of ancient Egypt, and the 19th and-early-20th-century occult revival. A temporal rift in the collection is evident, roughly divided between works from the 17th century and the 19th century. The exhibition's topical boundaries are drawn by the Fairweather Collection itself—both its strengths and weaknesses. The curators reviewed the collection of nearly 300 volumes and identified major areas of concentration: astrology, astronomy, astrological medicine, alchemy and hermeticism, witchcraft, and prophecy and prognostication. Some topics, though not documented with great depth in the Fairweather Collection, are nonetheless featured because of their novelty or significance within the framework of the history of the occult. These include Merlin, magic and spells, Aleister Crowley, Egyptology, and cartomancy. Where relevant, books from the general rare book collection are included to enhance and illuminate a subject. -

Dion Fortune and Her Inner Plane Contacts: Intermediaries in the Western Esoteric Tradition

1 Dion Fortune and her Inner Plane Contacts: Intermediaries in the Western Esoteric Tradition Volume 1 of 2 Submitted by John Selby to the University of Exeter as a thesis for the degree of Doctor of Philosophy in Theology June 2008 This thesis is available for Library use on the understanding that it is copyright material and that no quotation from this thesis may be published without proper acknowledgement. I certify that all material in this thesis which is not my own work has been identified and that no material has been previously submitted and approved for the award of a degree at this or any other University. 2 _________________________ Abstract Whereas occultists of the standing of H. P. Blavatsky, Annie Besant, C. W. Leadbeater, and especially Aleister Crowley have been well served by academic enquiry and by published accounts of their lives and work, Violet Evans, neé Firth (aka ‘Dion Fortune’), has suffered comparative neglect, as has her concept of the ‘Masters’ who inspired and informed her work. These factors, alongside the longevity of her Society of the Inner Light (still flourishing), are the catalysts for my embarking on this thesis. Chapter 1 discusses the method of approach, covers Fortune’s definitions of frequent occult terms, and compares observations of her work by fellow occultists and outside observers. Chapter 2 is a comprehensive review of mainly recent academic research into the role of intermediaries in magic and religion from ancient times, and serves as a background to Fortune’s own esoteric philosophy, showing that she was heir to a tradition with a long history. -

Magical Realism As Literary Activism in the Post-Cold War US Ethnic Novel

Momentary Magic: Magical Realism as Literary Activism in the Post-Cold War US Ethnic Novel Dissertation Presented in Partial Fulfillment of the Requirements for the Degree Doctor of Philosophy in the Graduate School of The Ohio State University BY Anne Mai Yee Jansen M.A., M.Ed., B.A. Graduate Program in English The Ohio State University 2013 Dissertation Committee: Chadwick Allen, Advisor Pranav Jani Martin Joseph Ponce Copyright by Anne Mai Yee Jansen 2013 Abstract In the aftermath of the Cold War, the social climate was largely hostile toward minority activist rhetoric. In this era, some US writers of color turned to magical realism – a genre typically associated with Latin American authors of the 1960s – to criticize social injustice through the use of magic. Magical realism interrogates historical and social conditions through supernatural, mythical, or other non-realist characters and events. In many otherwise realist novels by US writers of color, moments of magic disrupt concepts of “reality” and complicate social and political inequalities. My comparative study investigates the intersections of magic, politics, and activism in magical realist novels by African American, Asian American, Chicano/Latino, and Native American authors by organizing the chapters around four recurrent themes: history, haunting, folklore, and shifting borders. This project explores how alternative visions of empowerment and engagement open up space within which writers of color can work against oppressive forces of racism and imperialism. I begin by tracing the genealogy of the term “magical realism,” acknowledging the problems inherent in this term before turning to the genre’s foundation in postcolonial nations and its historical use as a vehicle for anti-imperialist critiques. -

The Catholic Church and the Future of Fortune-Telling

May 20, 2018 The Catholic Church and the future of fortune-telling When we think of prophets, we tend to think of Isaiah, Elijah or Anna — men and women who shared a message of hope and peace (and/or death and destruction) given them directly by the Heavenly Father. Isaiah, for instance, told about Jesus several centuries before He was born! Isaiah said that a “servant” would suffer and die to save others from their sins. Further, Isaiah said that this man would be buried in a rich man's tomb, and that despite his suffering and death, he would be a light in the darkness. Lesser known is the fact that he also said the Savior would have a dog named Winston who was “beloved amongst the 12”. While the Gospels don’t mention Winston, the historian Josephus does include a brief reference to a “gentle Labrador whom the Christ loved and allowed at the Last Supper, even though the Apostle James thought it was very unsanitary.” (As further proof, if you look very carefully at Da Vinci’s “The Last Supper,” you can just make out Winston under the table. I’ve placed this picture on our website, dcdiocese.org/swkscatholic.) Later there was Nostradamus, and later still, Edgar Cayce, although you wouldn’t exactly call them prophets. Both made predictions that caused some people to go, “Wow!” and others to say, “Meh.” I understand why the Catholic Church frowns on this sort of thing, including in regard to the fortune tellers of today: Jesus is our present and our future. -

NEW AGE GURU?: Testing Nostradamus's Message and Method

CHRISTIAN RESEARCH INSTITUTE P.O. Box 8500, Charlotte, NC 28271 Article: DN089 ASTROLOGER? OCCULTIST? NEW AGE GURU?: Testing Nostradamus’s Message and Method This article first appeared in the Christian Research Journal, volume 25, number 2 (2002) as a companion to the feature article Nostradamus: a Challenge to Biblical Prophecy? by Steve Bright. For further information or to subscribe to the Christian Research Journal go to: http://www.equip.org According to the prophetic test found in Deuteronomy 18:20–22, we know that Nostradamus was not a prophet of God because his prophesies failed to come to pass with 100 percent accuracy. We also have two other criteria by which we can evaluate the prophet and his enigmatic prophecies: his message and his method. MESSAGE Deuteronomy 13:1–5 says that even if a prophecy comes to pass, if its message leads people away from God, then it was not from God. What is Nostradamus’s message, and does it lead people away from God? Though there is good reason to question his sincerity, Nostradamus stated that his predictions were in harmony with the Catholic faith and Scripture: I protest before God and his Saints that I do not propose to insert any writings in this present Epistle that will be contrary to the true Catholic faith…. (Epistle, par. 9) The eternal God alone, who is the thorough searcher of human hearts, pious, just and merciful, is the true judge…. (Epistle, par. 8) From the time of David to that of our Saviour and Redeemer, Jesus Christ, born of the unique virgin….