02 Introduction-Chapter II Nurdin

Total Page:16

File Type:pdf, Size:1020Kb

Load more

Recommended publications

-

Buku Muhammadiyah 100 Tahun Menyinari Negeri

Muhammadiyah Muhammadiyah 100 Tahun Menyinari Negeri MAJELIS PUSTAKA DAN INFORMASI PIMPINAN PUSAT MUHAMMADIYAH 100 Tahun Menyinari Negeri Muhammadiyah Muhammadiyah 100 Tahun Menyinari Negeri Penanggung Jawab: Drs. H. Muchlas, M.T. “Aku titipkan Muhammadijah ini kepadamu, dengan penuh (Ketua Majelis Pustaka dan Informasi PP Muhammadiyah) harapan agar Muhammadijah dapat dipelihara dan didjaga den- Tim Penyusun: M. Raihan Febriansyah, Arief Budiman Ch., Yazid R. Passandre gan sesungguhnja. Karena dipelihara dan didjaga, hendaklah da- M. Amir Nashiruddin, Widiyastuti, Imron Nasri pat abadi hidup Muhammadijah kita. Memelihara dan mendjaga Tim Usaha dan Produksi: Muhammadijah, bukan pekerdjaan jang mudah, maka aku tetap Muhammad Purwana, Sarikin Busman berdo’a setiap masa dan ketika dihadapkan Ilahi Rabbi. Begitu Tim Asistensi: Rizky Taruna, Dwi Priyanto, Eko Priyanto pula mohon berkat restu do’a limpahan rahmat karunia Allah, Diterbitkan oleh: agar Muhammadijah tetap madju, berbuah dan memberi man- Majelis Pustaka dan Informasi Pimpinan Pusat Muhammadiyah Jl. KHA Dahlan 103 Yogyakarta 55262 faat bagi seluruh manusia sepandjang masa, dari zaman ke za- Telp. 0274-375025 Fax. 0274-381031 man. Dan aku berdo’a agar kamu sekalian jang mewarisi, mend- e-mail: [email protected] website: www.muhammadiyah.or.id jaga dan memadjukan Muhammadijah.” isbn: 979-xxxxx-0-x (K.H. Ahmad Dahlan, 1923) ii iii 100 Tahun Menyinari Negeri Muhammadiyah Kata Pengantar TIM PENYUSUN Alhamdulillah, akhirnya buku ini terbit juga. Ini adalah monumen sejarah yang penting. Seratus tahun perjalanan gerakan Muhammadiyah adalah sesuatu yang sudah seharusn- ya disyukuri dan salah satu bentuk kesyukuran itu adalah penerbitan buku ini. Buku ini ditulis dalam tiga bagian. Bagian pertama, mengisahkan perjalanan 100 tahun yang telah dilalui Muhammadiyah secara singkat dan momen-momen penting perkem- bangan organisasi ini. -

Islamic Student Organizations and Democratic Development In

ISLAMIC STUDENT ORGANIZATIONS AND DEMOCRATIC DEVELOPMENT IN INDONESIA: THREE CASE STUDIES A thesis presented to the faculty of the Center for International Studies of Ohio University In partial fulfillment of the requirements for the degree Master of Arts Troy A. Johnson June 2006 This thesis entitled ISLAMIC STUDENT ORGANIZATIONS AND DEMOCRATIC DEVELOPMENT IN INDONESIA: THREE CASE STUDIES by TROY A. JOHNSON has been approved for the Center of International Studies Elizabeth F. Collins Associate Professor of Classics and World Religions Drew McDaniel Interim Dean, Center for International Studies Abstract JOHNSON, TROY A., M.A., June 2006, International Development Studies ISLAMIC STUDENT ORGANIZATIONS AND DEMOCRATIC DEVELOPMENT IN INDONESIA: THREE CASE STUDIES (83 pp.) Director of Thesis: Elizabeth F. Collins This thesis describes how and to what extent three Islamic student organizations – Muhammadiyah youth groups, Kesatuan Aksi Mahasiswa Muslim Indonesia (KAMMI), and remaja masjid – are developing habits of democracy amongst Indonesia's Muslim youth. It traces Indonesia's history of student activism and the democratic movement of 1998 against the background of youth violence and Islamic radicalism. The paper describes how these organizations have developed democratic habits and values in Muslim youth and the programs that they carry out towards democratic socialization in a nation that still has little understanding of how democratic government works. The thesis uses a theoretical framework for evaluating democratic education developed by Freireian scholar Ira Shor. Finally, it argues that Islamic student organizations are making strides in their efforts to promote inclusive habits of democracy amongst Indonesia's youth. Approved: Elizabeth F. Collins Associate Professor or Classics and World Religions Acknowledgments I would like to thank my friends in Indonesia for all of their openness, guidance, and support. -

Tat Twam Asi Based Role-Playing Learning Model in Social Studies Knowledge Competence

International Journal of Elementary Education. Volume 4, Number 2, Tahun 2020, pp. 187-199 LOGO P-ISSN: 2579-7158 E-ISSN: 2549-6050 Open Access: https://ejournal.undiksha.ac.id/index.php/IJEE Jurnal Tat Twam Asi Based Role-Playing Learning Model in Social Studies Knowledge Competence Kadek Dwi Intan Agustini1*, I Made Suarjana2 I Nyoman Laba Jayanta3 Ndara Tanggu Renda4 1234Elementary School Teacher Education Study Program, FIP, Undiksha, Indonesia A R T I C L E I N F O A B S T R A K Article history: Rendahnya kompetensi pengetahuan IPS yang dimiliki siswa akibat Received 18 March 2020 kurang aktifnya siswa dalam proses pembelajaran, hal ini menjadi salah Received in revised form satu alasan penelitian ini dilakukan. Tujuan penelitian ini adalah untuk 30 April 2020 Accepted 5 May 2020 mengetahui pengaruh model pembelajaran Role-Playing berbasi Tat Available online 15 May Twam Asi terhadap penguasaan kompetensi pengetahuan IPS. 2020 Penelitian ini merupakan penelitian quasi experiment dengan desain nonequivalent post-test only control group. Populasi dalam penelitian ini kata kunci: adalah seluruh kelas V SD Gugus IV Kecamatan Buleleng Kabupaten role-playing, tat twam asi Buleleng yang berjumlah 5 kelas dengan jumlah 172 siswa. Sampel dalam penelitian ini yaitu SD Negeri 1 Banyuasri sebagai kelompok keywords: eksperimen dengan jumlah 35 siswa dan SD Negeri 5 Banyuasri role-playing, tat twam asi sebagai kelompok kontrol yang berjumlah 32 siswa yang diambil dengan teknik group desain random sampling. Pengumpulan data kompetensi pengetahuan IPS dilakukan dengan menggunakan tes pilihan ganda. Data dianalisis dengan statistik deskriptif dan statistik inferensial yaitu uji t-test polled varians. -

Pembaharuan Pendidikan Perspektif Ahmad Dahlan

PEMBAHARUAN PENDIDIKAN PERSPEKTIF AHMAD DAHLAN Erjati Abbas Universitas Islam Negeri (UIN) Raden Intan Lampung Email: [email protected] Abstract The Islamic reform movement in Indonesia cannot be separated from the figure of Ahmad Dahlan through the Muhammadiyah organization. This can be traced through the early history and development of Muhammadiyah which was shown by Ahmad Dahlan's character through the idea of renewal or the tajdid movement. This article looks at the character of KH. Ahmad Dahlan from an anthropological and sociological perspective. The reading is intended to determine the role of the character in the map of the development of the community. The main thing to be examined in this article is the correlation between KH. Ahmad Dahlan and the pesantren education system in Indonesia. The correlation between Muhammadiyah and Islamic boarding schools was studied using the discussion of the categorical simplification model on three indicators of Muhammadiyah's function and role, namely as an educational institution and the development of Islamic teachings, as an institution for Islamic struggle and da'wah, and as an institution for community empowerment and service. From the three categories it can be seen that KH. Ahmad Dahlan is a figure who is able to respond to the latest challenges quickly and precisely through the tajdid (renewal) movement in the fields of education, preaching, and empowering the Indonesian people. Keywords: Ahmad Dahlan, Renewal, Education, Da'wah, Community Empowerment. Abstrak Gerakan pembaharuan Islam di Indonesia tidak bisa dilepaskan dari sosok Ahmad Dahlan melalui organisasi Muhammadiyah. Hal ini dapat ditelusuri melalui sejarah awal dan perkembangan Muhammadiyah yang ditunjukkan oleh ketokohan Ahmad Dahlan melalui ide pembaharuan atau gerakan tajdid. -

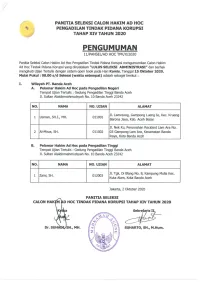

PENGUMUMAN Ll/PANSEL/AD HOC TPK/X/2020

PANITIA SELEKSI CALON HAKIM AD HOC PENGADILAN TINDAK PIDANA KORUPSI TAHAP XIV TAHUN 2020 PENGUMUMAN ll/PANSEL/AD HOC TPK/X/2020 Panitia Seleksi Calon Hakim Ad Hoc Pengadilan Tindak Pidana Korupsi mengumumkan Calon Hakim Ad Hoc Tindak Pidana Korupsi yang dinyatakan "LULUS SELEKSI ADMINISTRASI" dan berhak mengikuti Ujian Tertulis dengan sistem open book pada Hari Kamis, Tanggal 15 Oktober 2020, Mulai Pukul : 08.00 s/d Selesai (waktu setempat) adalah sebagai berikut : I. Wilayah PT. Banda Aceh A. Pelamar Hakim Ad Hoc pada Pengadilan Negeri Tempat Ujian Tertulis : Gedung Pengadilan Tinggi Banda Aceh Jl. Sultan Alaidinmahmudsyah No. 10 Banda Aceh 23242 NO. NAMA NO. UJIAN ALAMAT Jl. Lamreung, Gampong Lueng Ie, Kec. Krueng 1 Usman, SH.I., MH. 011001 Barona Jaya, Kab. Aceh Besar Jl. Nek Ku, Perumahan Recident Lam Ara No. 2 Al-Mirza, SH. 011002 03 Gampong Lam Ara, Kecamatan Banda Raya, Kota Banda Aceh B. Pelamar Hakim Ad Hoc pada Pengadilan Tinggi Tempat Ujian Tertulis : Gedung Pengadilan Tinggi Banda Aceh Jl. Sultan Alaidinmahmudsyah No. 10 Banda Aceh 23242 NO. NAMA NO. UJIAN ALAMAT Jl. Tgk. Di Blang No. 8, Kampung Mulia Kec. 1 Zaini, SH. 012003 Kuta Alam, Kota Banda Aceh Jakarta, 2 Oktober 2020 PANITIA SELEKSI CALON HAKIM AD HOC TINDAK PIDANA KORUPSI TAHAP XIV TAHUN 2020 Dr. SUHA SUHARTO, SH., M.Hum. PANITIA SELEKSI CALON HAKIM AD HOC PENGADILAN TINDAK PIDANA KORUPSI TAHAP XIV TAHUN 2020 PENGUMUMAN ll/PANSEL/AD HOC TPK/X/2020 Panitia Seleksi Calon Hakim Ad Hoc Pengadilan Tindak Pidana Korupsi mengumumkan Calon Hakim Ad Hoc Tindak Pidana Korupsi yang dinyatakan "LULUS SELEKSI ADMINISTRASI" dan berhak mengikuti Ujian Tertulis dengan sistem open book pada Hari Kamis, Tanggal 15 Oktober 2020, Mulai Pukul : 08.00 s/d Selesai (waktu setempat) adalah sebagai berikut : II. -

BAB I PENDAHULUAN A. Latar Belakang Masalah Al-Qur'an Ialah

BAB I PENDAHULUAN A. Latar Belakang Masalah Al-Qur’an ialah kitab suci yang merupakan sumber utama bagi ajaran Islam. Melalui al-Qur’an sebagai sumber utama ajaran Islam, manusia mendapatkan petunjuk tentang semua ajaran-ajaran agama Islam. Melalui al- Qur’an pula manusia memperoleh petunjuk tentang semua perintah-perintah dan larangan-larangan Allah SWT yang diturunkan kepada nabi Muhammad SAW untuk disampaikan kepada seluruh umat manusia. Hal ini menunjukkan bahwa kedudukan al-Qur’an sangat penting bagi umat Islam sebagai sumber utama bagi ajaran yang diturunkan oleh Allh SWT. Berdasarkan definisinya, al-Qur’an memiliki arti sebagai kalam Allah SWT yang diturunkan (diwahyukan) kepada Nabi Muhammad SAW melalui perantaraan malaikat Jibril, yang merupakan mukjizat, diriwayatkan secara mutawatir, ditulis dalam sebuah mushaf, dan membacanya adalah sebuah 1 ibadah. Al-Qur’an merupakan mukjizat bagi Nabi Muhammad SAW yang berisi kalam Allah yang penuh dengan pembelajaran berupa hal-hal yang diperintahkan dan dilarang-Nya. Hal-hal yang diperintahkan Allah termaktub seluruhnya dalam al-Qur’an untuk kemudian kewajiban bagi umat Islam 1 Ahmad Syarifuddin, Mendidik Anak Mambaca, Menulis, dan Mencintai Al-Qur’an,( Jakarta: 2004), hal. 16 1 mengerjakan dan mematuhinya seperti, kewajiban bagi umat Islam untuk melaksanakan shalat, zakat, puasa, dan lain-lain. Larangan-larangan dari Allah juga dijelaskan dalam al-Qur’an sebagai rambu-rambu bagi umat Islam dalam bertindak dan berperilaku dalam kehidupannya selama di dunia ini. Larangan- larangan itu misalnya, diharamkannya minum minuman keras, memakan daging babi, melakukan tindak pembunuhan, perjudian dan lain-lain. Al-Qur’an juga sebagai salah satu rahmat yang tak ada taranya bagi alam semesta, karena di dalamnya terkumpul wahyu Ilahi yang menjadi petunjuk, pedoman dan pelajaran bagi siapa yang mempercayai serta mengamalkannya. -

A. R. Fakhruddin: the Face of Tasawuf in Muhammadiyah

A. R. FAKHRUDDIN: THE FACE OF TASAWUF IN MUHAMMADIYAH By: Masyitoh* Abstract With emphasizing to truth Islam and refusal to taqlid, bid’ah and churafat, Muhammadiyah has appreciation to Islamic mysticism (read: akhlaki Islamic mysticism). Although Islamic mysticism is more individual necessity and the term has never been mentioned, but many of Muhammadiyah figures practice Islamic mysticism individually. It was began from founder of Muhammadiyah, K.H. Ahmad Dahlan and others figures, such as: Ki Bagus Hadikusumo, K.H. Mas Mansyur, Buya Hamka, AR.Fakhruddin,etc. A.R Fakhruddin him self can be addressed as Kadda an yukuuna Suufiyan (near to be a Sufi), in this case Sufi Akhlaqi. It is caursed by all akhlakul karimah characteristics have already mixed up in his soul, such as: patient, thank God, Wara Zuhud, Qana’ah, Tawwakal, Ikhlas, Risha, etc. In the meantime, his spiritual life which fills more of his life and it is reflecting Islamic mysticism attitudes. A Sufi’s live can be reflected from his attitude and thought about: taubat, taqarrub, dzikullah, khusyu’, tawaddhu’, khauf, raja, muraqobah, and istiqamah, these maqam are common to be done in Islamic mysticism world. Keyword : Muhammadiyah, mysticism, Sufi Akhlaqi, Spiritual and maqam. A. Introduction The birth of Muhammadiyah movement in the early 20th century, precisely on 8 Dzulhijjah 1330 H, or on 18th of November 1912, at least, is because of the influence of tajdid movement (reformation, the renewal of Islamic thought) which was sparked by Muhammad Ibn ‘Abd al-Wahab (1703-1792) in the Emirate Arab, Muhammad Abduh (1849-1905), Muhammad Rasyid Ridha (1865-1935) in Egypt, and soon. -

Denys Lombard and Claudine Salmon

Is l a m a n d C h in e s e n e s s Denys Lombard and Claudine Salmon It is worth pausing for a moment to consider the relationships that were able to exist between the expansion of Islam in the East Indies and the simultaneous formation of "Chinese" communities. These two phenomena are usually presented in opposition to one another and it is pointless here to insist on the numerous conflicting accounts, past and present.* 1 Nevertheless, properly considered, it quickly becomes apparent that this is a question of two parallel developments which had their origins in the urban environment, and which contributed to a large extent to the creation of "middle class" merchants, all driven by the same spirit of enterprise even though they were in lively competition with one another. Rather than insisting once more on the divergences which some would maintain are fundamental—going as far as to assert, against all the evidence, that the Chinese "could not imagine marrying outside their own nation," and that they remain unassimilable—we would like here to draw the reader's attention to a certain number of long-standing facts which allow a reversal of perspective. Chinese Muslims and the Local Urban Mutation of the 14th-15th Centuries No doubt the problem arose along with the first signs of the great urban transformation of the 15th century. The fundamental text is that of the Chinese (Muslim) Ma Huan, who accompanied the famous Admiral Zheng He on his fourth expedition in the South Seas (1413-1415), and reported at the time of their passage through East Java that the population was made up of natives, Muslims (Huihui), as well as Chinese (Tangren) many of whom were Muslims. -

![IIAS Logo [Converted]](https://docslib.b-cdn.net/cover/2769/iias-logo-converted-562769.webp)

IIAS Logo [Converted]

Women from Traditional Islamic Educational Institutions in Indonesia Educational Institutions Indonesia in Educational Negotiating Public Spaces Women from Traditional Islamic from Traditional Islamic Women Eka Srimulyani › Eka SrimulyaniEka amsterdam university press Women from Traditional Islamic Educational Institutions in Indonesia Publications Series General Editor Paul van der Velde Publications Officer Martina van den Haak Editorial Board Prasenjit Duara (Asia Research Institute, National University of Singapore) / Carol Gluck (Columbia University) / Christophe Jaffrelot (Centre d’Études et de Recherches Internationales-Sciences-po) / Victor T. King (University of Leeds) / Yuri Sadoi (Meijo University) / A.B. Shamsul (Institute of Occidental Studies / Universiti Kebangsaan Malaysia) / Henk Schulte Nordholt (Royal Netherlands Institute of Southeast Asian and Caribbean Studies) / Wim Boot (Leiden University) The IIAS Publications Series consists of Monographs and Edited Volumes. The Series publishes results of research projects conducted at the International Institute for Asian Studies. Furthermore, the aim of the Series is to promote interdisciplinary studies on Asia and comparative research on Asia and Europe. The International Institute for Asian Studies (IIAS) is a postdoctoral research centre based in Leiden and Amsterdam, the Netherlands. Its objective is to encourage the interdisciplinary and comparative study of Asia and to promote national and international cooperation. The institute focuses on the humanities and social -

The Effectiveness of Learning Hijaiyah Letters of Iqro

https://journal.islamicateinstitute.co.id/index.php/jaims The Effectiveness of Learning Hijaiyah Letters of Iqro’ Method (Case Study in Group B Ages 5-6 Years in Kindergarten Bustanul Athfal 1 Sukabumi) Leonita Siwiyanti Universitas Muhammadiyah Sukabumi, Indonesia [email protected] (CorrespondinG Author) Ira Nuryani TK Aisyiyah Bustanul Athfal Sukabumi, Indonesia [email protected] Elnawati Universitas Muhammadiyah Sukabumi, Indonesia [email protected] Arizal Eka Putra Universitas Muhammadiyah Lampung, Indonesia [email protected] Abstract This study aims to determine the learninG process of HiJaiyah letters, determine the supportinG factors and constraints, and to determine the effectiveness of learninG Hijaiyah letters of Iqro’ method in KinderGarten Bustanul Athfal 1 Sukabumi for children aGed 5-6 years. This research uses a qualitative approach with descriptive research. The results of the process of implementing the data with the Hijaiyah letters of Iqro’ method is carried out in accordance with the curriculum that schedules the Iqro method which is held every three times in one week. Hijaiyah letters of Iqro’ techniques are done privately/ individually and CBSA (active student learninG). SupportinG and inhibiting factors in implementinG the method are occurred as internal and external factors. From observational data and interviews that have been conducted, the method applied in KinderGarten Bustanul Athfal 1 Sukabumi is effective. Keywords: Iqro’ Method, Learning, Hijaiyah letters, Early Childhood. Efektivitas Pembelajaran Huruf Hijaiyah Metode Iqro' (Studi Kasus pada Grup-B Usia 5-6 Tahun di TK Aisyiyah Bustanul Atfal 1 Sukabumi) Abstrak Penelitian ini bertuJuan untuk mengetahui proses pembelaJaran huruf HiJaiyah, mengetahui faktor-faktor pendukunG dan kendala, dan untuk menGetahui efektivitas metode pembelaJaran huruf HiJaiyah Iqro' di TK Aisyiyah Bustanul Atfhal 1 untuk anak usia 5-6 tahun. -

THE HISTORY of the GROWTH and DEVELOPMENT of the BIG ISLAMIC ORGANIZATIONS in INDONESIA (A Study on Muhammadiyah, Nahdhatul Ulama and Al-Jam'iyatul Washliyah)

149 The History of Growth and Development THE HISTORY OF THE GROWTH AND DEVELOPMENT OF THE BIG ISLAMIC ORGANIZATIONS IN INDONESIA (A Study on Muhammadiyah, Nahdhatul Ulama and Al-Jam'iyatul washliyah) By: Junaidi Arsyad Jurusan Pendidikan Agama Islam UIN Sumatera Utara, Medan E-mail:[email protected] ABSTRAK Salah satu tujuan didirikannya organisasi Islam besar di Indonesia oleh para pemimpin muslim sebagai upaya bersama melawan penjajahan. Sekaligus juga berusaha memajukan bangsa Indonesia melalui pendidikan yang dikelola oleh organisasi. Semua asosiasi dan organisasi bertujuan untuk mempromosikan Islam dan keluar dari belenggu dan cengkeraman penjajah. Penelitian ini menggunakan metode deskriptif analitik, yaitu bekerja dengan cara mengumpulkan dari sumber bahan bacaan yang ada, kemudian membuat kerangka tertulis sesuai dengan metode yang diinginkan, kemudian ditemukan informasi tentang tumbuh kembang organisasi Islam besar di Indonesia antara lain Muhammadiyah, Nahdhatul. Ulama dan Al- Jam'iyatul Washliyah. Kata Kunci: Pertumbuhan, Perkembangan, Organisasi Islam ABSTRACT One of the goals of the establishment of a large Islamic organization in Indonesia by Muslim leaders as a joint effort to fight against colonialism. At the same time also trying to advance the Indonesian nation through education managed by the organization. All associations and organizations aim to promote Islam and get out of the shackles and clutches of the invaders. This research uses analytical descriptive method, which works by collecting from the source of existing reading materials, then create a written framework as desired in the method, then found information about the growth and development of large Islamic organizations in Indonesia, among others Muhammadiyah, Nahdhatul Ulama and Al-Jam'iyatul Washliyah. -

Contribution of Siti Walidah in the Nation Character Building Through ‘Aisyiyah Movement

CONTRIBUTION OF SITI WALIDAH IN THE NATION CHARACTER BUILDING THROUGH ‘AISYIYAH MOVEMENT Lingga Wisma Cahyaningrum and Ma’arif Jamuin Student at Islamic Religious Education Faculty of Islamic Studies, Universitas Muhammadiyah Surakarta e-mail: [email protected]., [email protected] Abstract-Siti Walidah is a reformer, the founder of ‘Aisyiyah, and also promoter of the nation character building. Her contribution in the efforts to establish the nation character has been manifested in formal and informal education, and social movement since 1918. She also did a breakthrough in her era by setting up ‘Aisyiyah along with its various activities, particularly the initiative in providing Islamic education for women. The movement is guided by the Quran and Sunnah in the framework of the nation character building with Prophet Muhammad as the role model. The guideline of the movement is beautifully reflected in ‘Aisyiyah Mars, which is still amendable until now. Keywords: Contribution, ‘Aisyiyah, Character Education, Mars ‘Aisyiyah Abstrak-Siti Walidah merupakan seorang tokoh pembaharu, pendiri gerakan ‘Aisyiyah dan peletak dasar model pembangunan karakter bangsa. Kontribusi Walidah dalam membangun karakter bangsa melalui pendidikan formal, pendidikan informal dan gerakan social sejak tahun 1918 telah membuahkan hasil bagi bangsa Indonesia. Mutiara pemikirannya diwujudkan dalam gerakan ‘Aisyiyah melalui berbagai macam kegiatan. Ia bergerak aktif di bidang pendidikan Islam untuk kaum perempuan. Gerakannya sentantiasa berpedoman pada Alquran dan sunnah dalam kerangka membangun karakter bangsa dengan meneladani Akhlak Rasulullah SAW. Panduan gerakannya tertulis indah dalam lagu mars ‘Aisyiyah, yang berkemajuan hingga sekarang. Kata Kunci: Kontribusi, ‘Aisyiyah, Pendidikan Karakter, Mars ‘Aisyiyah 68 - ISEEDU Volume 2, Nomor 1, May 2018 Contribution of Siti..