Teaching Data and Computational Journalism

Total Page:16

File Type:pdf, Size:1020Kb

Load more

Recommended publications

-

The Future of Investigative Journalism: Global, Networked and Collaborative

The Future of Investigative Journalism: Global, Networked and Collaborative Ellen Hume and Susan Abbott March 2017 Note: This report is extracted from our recent evaluation of the Global Investigative Journalism Network (GIJN) for the Adessium Foundation. Ellen Hume would like to thank especially David Kaplan, Susan Abbott, Anya Schiffrin, Ethan Zuckerman, James Hamilton, Tom Rosenstiel, Bruce Shapiro, Marina Guevara Walker and Brant Houston for their insights. 2 1. Overview: The Investigative Media Landscape The internet and DIY communication tools have weakened the commercial mainstream media, and authoritarian political actors in many once-promising democratic regions are compromising public media independence. Fewer journalists were murdered in 2016 than the previous year, but the number of attacks on journalists around the world is “unprecedented,” according to the Index on Censorship.1 Even the United States, once considered the gold standard for press freedom, has a president who maligns the mainstream news media as “enemies of the people.” An unexpectedly bright spot in this media landscape is the growth of local and cross-border investigative journalism, including the emergence of scores of local nonprofit investigative journalism organizations, often populated by veterans seeking honest work after their old organizations have imploded or been captured by political partisans. These journalism “special forces,” who struggle to maintain their independence, are working in dangerous environments, with few stable resources to support them. Despite the dangers and uncertainties, it is an exciting time to be an investigative journalist, thanks to new collaborations and digital tools. These nonprofits are inventing a potent form of massive, cross-border investigative reporting, supported by philanthropy. -

JOUR 322: Data Journalism 2 Units

JOUR 322: Data Journalism 2 units Fall 2017 Section: 21176D Wednesdays, 2-3:40 p.m. Location: ANN 408 Instructor: Dana Chinn, Lecturer Office: ASC 227 Office Hours: By appointment Tuesdays, 10-11:50 a.m. and 2-4 p.m. Wednesdays, noon to 1:50 p.m. Other days and times are available. Email: [email protected] I. Course Description Proficiency with gathering, analyzing and visualizing data is essential in journalism today as commodity content becomes increasingly ineffective in both serving the public interest and engaging audiences. This two-unit introduction to data journalism builds upon the reporting skills you developed in JOUR 207/307, Reporting and Writing I and II. Those courses focused on identifying and interviewing people as sources. This course introduces you to using data as a source, and “interviewing” datasets using quantitative analysis and data visualization tools. In the past, a “data story” was a big investigation produced by a separate data journalist team that included statisticians and coders. However, good reporting always did include using numbers to compare, contrast and other put facts and opinions into perspective. And “[n]ow, the fear of numbers marks a reporter as one who can only do part of the job,” according to Sarah Cohen, New York Times data journalist and the author of Numbers in the Newsroom, the primary textbook that we’ll use. In this frenzied media climate, it’s more important than ever for journalists to gather and analyze data themselves rather than rely on a source’s summary and interpretation. Thus, this course will start with building the fundamental skills you need to find and use data in basic news stories and beat reporting. -

Download Annual Report

The New Conservative Flagship ANNUAL REPORT 2020A About American Compass Table of Contents Our Mission To restore an economic consensus that emphasizes the importance of family, community, and industry to the nation’s liberty and prosperity: 1 Founder’s Letter 4 REORIENTING POLITICAL FOCUS from growth for its own sake to widely shared economic development that sustains vital social institutions. SETTING A COURSE for a country in which families can achieve self- sufficiency, contribute productively to their communities, and prepare the next 2 Year in Review 10 generation for the same. Conservative Flagship 12 HELPING POLICYMAKERS NAVIGATE the limitations that markets and government each face in promoting the general welfare and the nation’s security. Changing the Debate 14 Our Activities Creating Community 16 AFFILIATION. Providing opportunities for people who share its mission to The Commons 18 build relationships, collaborate, and communicate their views to the broader political community. Our Growing Influence 20 DELIBERATION. Supporting research and discussion that advances understanding of economic and social conditions and tradeoffs through study of history, analysis of data, elaboration of theory, and development of policy 3 Our Work 21 proposals. ENGAGEMENT. Initiating and facilitating public debate to challenge existing Rebooting the American System 22 orthodoxy, confront the best arguments of its defenders, and force scrutiny of unexamined assumptions and unconsidered consequences. Coin-Flip Capitalism 26 Our Principles Moving the Chains 30 AMERICAN COMPASS strives to embody the principles and practices of a healthy democratic polity, combining intellectual combat with personal civility. Corporate Actual Responsibility 34 We welcome converts to our vision and value disagreement amongst A Seat at the Table 38 our members. -

The Potential and Reality of Data Journalism in Developing Media Markets Table of Contents

The Potential and Reality of Data Journalism in Developing Media Markets Table of contents The Internews Approach 4 Data Journalism in Myanmar’s Emerging Open Data Community 5 Recommendations to Accelerate Myanmar’s Open Data Movement 8 Examples 10 ata HAS THE poteNtiaL to HELP communities understand their biggest challenges – why people become sick or Dwell, why development initiatives succeed or fail, how government actions align with citizens’ priorities. However, most people do not have the skills or inclination to engage with data directly. That’s where data journalists and the open data community come in. Every day governments, CSOs, and universities release more data related to issues vital to citizens including access to education, jobs and healthcare. In response to Internews data this growing supply of data, emerging open data communities around the world are journalism projects bringing together diverse players from civil society: government officials, scientists, cover a wide range technologists and journalists to understand data, what it means and why it matters. of challenges, from Data journalists are at the center of efforts to transform data into actionable revealing corruption and information. Working with others in the open data community, journalists make inequality to promoting sense of data in stories that show citizens how social and political issues affect their accountability and data- daily lives and help people can make better decisions. When data journalists are driven policy decisions. also local, they can be change agents at the community level, ushering in informed We have worked across democratic debate that is inclusive, lasting and meaningful. At a national level, data the globe, from Kenya driven stories promote accountability and can influence policy decisions in countries to Afghanistan to Brazil, with little history of civic engagement. -

How to Fund Investigative Journalism Insights from the Field and Its Key Donors Imprint

EDITION DW AKADEMIE | 2019 How to fund investigative journalism Insights from the field and its key donors Imprint PUBLISHER RESPONSIBLE PUBLISHED Deutsche Welle Jan Lublinski September 2019 53110 Bonn Carsten von Nahmen Germany © DW Akademie EDITORS AUTHOR Petra Aldenrath Sameer Padania Nadine Jurrat How to fund investigative journalism Insights from the field and its key donors Sameer Padania ABOUT THE REPORT About the report This report is designed to give funders a succinct and accessible introduction to the practice of funding investigative journalism around the world, via major contemporary debates, trends and challenges in the field. It is part of a series from DW Akademie looking at practices, challenges and futures of investigative journalism (IJ) around the world. The paper is intended as a stepping stone, or a springboard, for those who know little about investigative journalism, but who would like to know more. It is not a defense, a mapping or a history of the field, either globally or regionally; nor is it a description of or guide to how to conduct investigations or an examination of investigative techniques. These are widely available in other areas and (to some extent) in other languages already. Rooted in 17 in-depth expert interviews and wide-ranging desk research, this report sets out big-picture challenges and oppor- tunities facing the IJ field both in general, and in specific regions of the world. It provides donors with an overview of the main ways this often precarious field is financed in newsrooms and units large and small. Finally it provides high-level practical ad- vice — from experienced donors and the IJ field — to help new, prospective or curious donors to the field to find out how to get started, and what is important to do, and not to do. -

Dr J. Oliver Boyd-Barrett (2009)

Dr J. Oliver Boyd-Barrett (2009) 1 Oliver Boyd-Barrett Full Resume Education (Higher Education) Ph.D . (1978) From the Open University (U.K.). World wide news agencies: Development, organization, competition, markets and product. A study of Agence France Presse, Associated Press, Reuters and United Press to 1975. (UMI Mircofiche Author No.4DB 5008). BA Hons , (Class 2i) (1967). From Exeter University (U.K.). Sociology. (High School) GCE (General Certificate of Education)(U.K.): 'A' levels in History (Grade A), English Literature (Grade A), 'Special' paper in History (Grade 1), and Latin (AO), 1964; ‘0’ levels: passes in 10 subjects, including three ‘A’ grades; studied at Salesian College, Chertsey, Surrey (U.K.). Appointments and Experience (1) Full-time Appointments 2008- Professor (full), Department of Journalism, School of Communication Studies, Bowling Green State University, Ohio 2005-2008: Director, School of Communication Studies, Bowling Green State University, Ohio. 2001 - 2005: Full professor, tenured, Department of Communication in College of Letters, Arts and Social Sciences, California State Polytechnic University, Pomona (U.S.A.). 1998-2001: Associate Dean of the College of the Extended University, California State Polytechnic University, Pomona (U.S.A.). 1994-98: Director, Distance Learning, at the Centre for Mass Communications Research, Leicester University, and Director of the MA in Mass Communication (by distance learning) (U.K.). 1990-94: Sub-Dean (Courses) and Senior Lecturer, School of Education, at the Open University; Deputy Director MA in Education, 1992-3. (U.K.). 1985-90: Lecturer, School of Education, at the Open University (Language and Communications) (U.K.). 1975-85: Lecturer, School of Education, at the Open University (Administration and Management) (U.K.). -

Book Group to Go Book Group Kit Collection Glendale Public Library

Book Group To Go Book Group Kit Collection Glendale Public Library Titles in the Collection — Spring 2016 Book Group Kits can be checked out for 8 weeks and cannot be placed on hold or renewed. To reserve a kit, please contact: [email protected] or call 818.548.2041 The Absolutely True Diary of a Part-Time Indian by Sherman Alexie In his first book for young adults, bestselling author Sherman Alexie tells the story of Junior, a budding cartoonist growing up on the Spokane Indian Reservation. Determined to take his future into his own hands, Junior leaves his troubled school on the rez to attend an all-white farm town high school where the only other Indian is the school mascot. Heartbreaking, funny, and beautifully written, the book chronicles the contemporary adolescence of one Native American boy. Poignant drawings by acclaimed artist Ellen Forney reflect Junior’s art. 2007 National Book Award winner. Fiction. Young Adult. 229 pages The Abstinence Teacher by Tom Perrotta A controversy on the soccer field pushes Ruth Ramsey, the human sexuality teacher at the local high school, and Tim Mason, a member of an evangelical Christian church that doesn't approve of Ruth's style of teaching, to actually talk to each other. Adversaries in a small-town culture war, they are forced to take each other at something other than face value. Fiction. 358 pages The Age of Miracles by Karen Thompson Walker On a seemingly ordinary Saturday in a California suburb, Julia and her family awake to discover, along with the rest of the world, that the rotation of the earth has suddenly begun to slow. -

The Leadership Institute's Broadcast Journalism School

“They may teach you a lot in college, but the polishing tips you learn here are just Launch your broadcast the edge you need to get the journalism career job you want.” - Ashley Freer Lawrenceville, GA The Leadership Institute’s Broadcast Journalism School Balance the media -- be the media -- get a job in broadcast journalism If you’re a conservative student interested in a career in journalism, the Leadership Institute’s Broadcast Journalism School is for you. The BJS is an intense, two-day seminar that gives aspiring conservative journalists the skills necessary to bring balance to the media and succeed in this highly competitive field. Learn: l How to prepare a winning résumé tape l How to plan a successful step-by-step job hunt l The nuts-and-bolts of building a successful broadcasting career Thanks to these techniques, close to 100 BJS grads now have full-time jobs in TV news. To register visit www.leadershipinstitute.org or call 1-800-827-5323 Start your future today Get paid $3,000 during your unpaid internship! Register Today! Graduates of the Leadership Institute’s Broadcast Journalism School now have a new way to 2007 Training Sessions build a successful media career: The Balance in Media Fellowship March 31 - April 1 A Balance in Media Fellowship could help you afford an unpaid internship – whether Arlington, VA you’re interning at your local television station or for a national news network. July 31- July 22 With a Balance in Media Fellowship, you can: Arlington, VA l Receive up to $3,000 during your three-month internship l Gain real-life experience at your media internship October 27 - October 28 l Start your career as a conservative journalist Arlington, VA Just send in your application, and you could have up to $3,000 for your unpaid internship! For details and an application, call the Leadership Institute at (800) 827-5323. -

N Ieman Reports

NIEMAN REPORTS Nieman Reports One Francis Avenue Cambridge, Massachusetts 02138 Nieman Reports THE NIEMAN FOUNDATION FOR JOURNALISM AT HARVARD UNIVERSITY VOL. 62 NO. 1 SPRING 2008 VOL. 62 NO. 1 SPRING 2008 21 ST CENTURY MUCKRAKERS THE NIEMAN FOUNDATION HARVARDAT UNIVERSITY 21st Century Muckrakers Who Are They? How Do They Do Their Work? Words & Reflections: Secrets, Sources and Silencing Watchdogs Journalism 2.0 End Note went to the Carnegie Endowment in New York but of the Oakland Tribune, and Maynard was throw- found times to return to Cambridge—like many, ing out questions fast and furiously about my civil I had “withdrawal symptoms” after my Harvard rights coverage. I realized my interview was lasting ‘to promote and elevate the year—and would meet with Tenney. She came to longer than most, and I wondered, “Is he trying to my wedding in Toronto in 1984, and we tried to knock me out of competition?” Then I happened to keep in touch regularly. Several of our class, Peggy glance over at Tenney and got the only smile from standards of journalism’ Simpson, Peggy Engel, Kat Harting, and Nancy the group—and a warm, welcoming one it was. I Day visited Tenney in her assisted living facility felt calmer. Finally, when the interview ended, I in Cambridge some years ago, during a Nieman am happy to say, Maynard leaped out of his chair reunion. She cared little about her own problems and hugged me. Agnes Wahl Nieman and was always interested in others. Curator Jim Tenney was a unique woman, and I thoroughly Thomson was the public and intellectual face of enjoyed her friendship. -

In Praise of Statutes of Limitations in Sex Offense Cases James Herbie Difonzo Maurice A

Maurice A. Deane School of Law at Hofstra University Scholarly Commons at Hofstra Law Hofstra Law Faculty Scholarship 2004 In Praise of Statutes of Limitations in Sex Offense Cases James Herbie DiFonzo Maurice A. Deane School of Law at Hofstra University Follow this and additional works at: https://scholarlycommons.law.hofstra.edu/faculty_scholarship Recommended Citation James Herbie DiFonzo, In Praise of Statutes of Limitations in Sex Offense Cases, 41 Hous. L. Rev. 1205 (2004) Available at: https://scholarlycommons.law.hofstra.edu/faculty_scholarship/461 This Article is brought to you for free and open access by Scholarly Commons at Hofstra Law. It has been accepted for inclusion in Hofstra Law Faculty Scholarship by an authorized administrator of Scholarly Commons at Hofstra Law. For more information, please contact [email protected]. ARTICLE IN PRAISE OF STATUTES OF LIMITATIONS IN SEX OFFENSE CASES James Herbie DiFonzo* "Rapists Shouldn't Be Able to Run Out the Clock."' "'[DNA] is very, very reliable if you do two things right: if you test it right, and if you interpret the results right .... The problem is that jurors think it's absolute and infallible.'"2 TABLE OF CONTENTS I. INTRODUCTION ................................................................... 1206 II. ARE STATUTES OF LIMITATIONS STILL RELEVANT IN THE AGE OF DNA? .......................................................... 1209 A. Limitations Policy Revisited ....................................... 1209 B. The Impact of DNA Technology on Limitations Policy in Sexual Offense Cases ................................... 1217 C. Indicting "JohnDoe, Unknown Male with Matching Deoxyribonucleic Acid (DNA) Profile"........ 1226 * Professor of Law, Hofstra University School of Law. J.D., M.A., 1977, Ph.D., 1993, University of Virginia. E-mail: [email protected]. -

Fiction Resume

GREG GARRETT Professor of English/ 2013 Baylor Centennial Professor Baylor University Waco, TX 76798-7404 (254) 710-6879 [email protected] SELECTED PUBLICATIONS Nonfiction A Long, Long Way: Hollywood’s Unfinished Journey from Racism to Reconciliation. New York: Oxford University Press, 2020. A lead trade title for Spring 2020. Featured in Publishers Weekly, LitHub, Read the Spirit. In Conversation: Rowan Williams and Greg Garrett. With Rowan Williams. New York: Church Publishing, 2019/London: SPCK, 2020. Featured in Publishers Weekly, Read the Spirit, BBC Radio. The Courage to See: Daily Inspiration from Great Literature. With Sabrina Fountain. Louisville: Westminster John Knox Press, 2019. Featured in Read the Spirit, BBC Radio. Living with the Living Dead: The Wisdom of the Zombie Apocalypse. New York: Oxford University Press, 2017. A lead trade title for Spring 2017. Featured in The Spectator, Vice, Christianity Today, Church News, The Baptist Standard, BBC Radio, The Daily Mirror, Christianity, and many other media sources. Featured book at the Edinburgh International Festival of Books, the Greenbelt Festival (UK), and the Texas Book Festival. My Church Is Not Dying: Episcopalians in the 21st Century. New York: Morehouse Publishing, 2015. Featured in Christian Century. Entertaining Judgment: The Afterlife in Popular Imagination. Oxford: Oxford University Press, 2015. A lead trade title for Spring 2015. Starred review in Library Journal. Lead reviews in The New Statesman and Christianity Today. Excerpted as lead article in Salon.com and featured in Christian Century. Faithful Citizenship: Christianity and Politics for the 21st Century. Englewood, CO: Patheos Press, 2012. Featured in Read the Spirit. The Other Jesus: Leaving a Religion of Fear for the God of Love. -

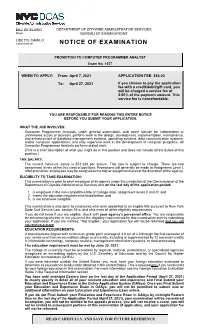

COMPUTER PROGRAMMER ANALYST Exam No

BILL DE BLASIO DEPARTMENT OF CITYWIDE ADMINISTRATIVE SERVICES Mayor BUREAU OF EXAMINATIONS LISETTE CAMILO Commissioner NOTICE OF EXAMINATION PROMOTION TO COMPUTER PROGRAMMER ANALYST Exam No. 1537 WHEN TO APPLY: From: April 7, 2021 APPLICATION FEE: $68.00 To: April 27, 2021 If you choose to pay the application fee with a credit/debit/gift card, you will be charged a service fee of 2.00% of the payment amount. This service fee is nonrefundable. YOU ARE RESPONSIBLE FOR READING THIS ENTIRE NOTICE BEFORE YOU SUBMIT YOUR APPLICATION. WHAT THE JOB INVOLVES: Computer Programmer Analysts, under general supervision, with some latitude for independent or unreviewed action or decision, perform work in the design, development, implementation, maintenance, and enhancement of database management systems, operating systems, data communication systems, and/or computer applications, and may supervise work in the development of computer programs. All Computer Programmer Analysts perform related work. (This is a brief description of what you might do in this position and does not include all the duties of this position.) THE SALARY: The current minimum salary is $51,233 per annum. This rate is subject to change. There are two assignment levels within this class of positions. Promotions will generally be made to Assignment Level I. After promotion, employees may be assigned to the higher assignment level at the discretion of the agency. ELIGIBILITY TO TAKE EXAMINATION: This examination is open to each employee of an agency under the jurisdiction of the Commissioner of the Department of Citywide Administrative Services who on the last day of the application period: 1.