Using the Natural Resistance of Motor Neuron Subpopulations to Identify Therapeutic Targets in Amyotrophic Lateral Sclerosis

Total Page:16

File Type:pdf, Size:1020Kb

Load more

Recommended publications

-

Role of Cyclosporine in Gingival Hyperplasia: an in Vitro Study on Gingival Fibroblasts

International Journal of Molecular Sciences Article Role of Cyclosporine in Gingival Hyperplasia: An In Vitro Study on Gingival Fibroblasts 1, , 2, 3 3 Dorina Lauritano * y , Annalisa Palmieri y, Alberta Lucchese , Dario Di Stasio , Giulia Moreo 1 and Francesco Carinci 4 1 Department of Medicine and Surgery, Centre of Neuroscience of Milan, University of Milano-Bicocca, 20126 Milan, Italy; [email protected] 2 Department of Experimental, Diagnostic and Specialty Medicine, University of Bologna, via Belmoro 8, 40126 Bologna, Italy; [email protected] 3 Multidisciplinary Department of Medical and Dental Specialties, University of Campania-Luigi Vanvitelli, 80138 Naples, Italy; [email protected] (A.L.); [email protected] (D.D.S.) 4 Department of Morphology, Surgery and Experimental Medicine, University of Ferrara, 44121 Ferrara, Italy; [email protected] * Correspondence: [email protected]; Tel.: +39-335-679-0163 These authors contributed equally to this work. y Received: 25 November 2019; Accepted: 13 January 2020; Published: 16 January 2020 Abstract: Background: Gingival hyperplasia could occur after the administration of cyclosporine A. Up to 90% of the patients submitted to immunosuppressant drugs have been reported to suffer from this side effect. The role of fibroblasts in gingival hyperplasia has been widely discussed by literature, showing contrasting results. In order to demonstrate the effect of cyclosporine A on the extracellular matrix component of fibroblasts, we investigated the gene expression profile of human fibroblasts after cyclosporine A administration. Materials and methods: Primary gingival fibroblasts were stimulated with 1000 ng/mL cyclosporine A solution for 16 h. Gene expression levels of 57 genes belonging to the “Extracellular Matrix and Adhesion Molecules” pathway were analyzed using real-time PCR in treated cells, compared to untreated cells used as control. -

Neural Control of Movement: Motor Neuron Subtypes, Proprioception and Recurrent Inhibition

List of Papers This thesis is based on the following papers, which are referred to in the text by their Roman numerals. I Enjin A, Rabe N, Nakanishi ST, Vallstedt A, Gezelius H, Mem- ic F, Lind M, Hjalt T, Tourtellotte WG, Bruder C, Eichele G, Whelan PJ, Kullander K (2010) Identification of novel spinal cholinergic genetic subtypes disclose Chodl and Pitx2 as mark- ers for fast motor neurons and partition cells. J Comp Neurol 518:2284-2304. II Wootz H, Enjin A, Wallen-Mackenzie Å, Lindholm D, Kul- lander K (2010) Reduced VGLUT2 expression increases motor neuron viability in Sod1G93A mice. Neurobiol Dis 37:58-66 III Enjin A, Leao KE, Mikulovic S, Le Merre P, Tourtellotte WG, Kullander K. 5-ht1d marks gamma motor neurons and regulates development of sensorimotor connections Manuscript IV Enjin A, Leao KE, Eriksson A, Larhammar M, Gezelius H, Lamotte d’Incamps B, Nagaraja C, Kullander K. Development of spinal motor circuits in the absence of VIAAT-mediated Renshaw cell signaling Manuscript Reprints were made with permission from the respective publishers. Cover illustration Carousel by Sasha Svensson Contents Introduction.....................................................................................................9 Background...................................................................................................11 Neural control of movement.....................................................................11 The motor neuron.....................................................................................12 Organization -

System Inflammation Macrophages/Microglia in Central Nervous Brain Dendritic Cells

Brain Dendritic Cells and Macrophages/Microglia in Central Nervous System Inflammation This information is current as Hans-Georg Fischer and Gaby Reichmann of September 25, 2021. J Immunol 2001; 166:2717-2726; ; doi: 10.4049/jimmunol.166.4.2717 http://www.jimmunol.org/content/166/4/2717 Downloaded from References This article cites 51 articles, 28 of which you can access for free at: http://www.jimmunol.org/content/166/4/2717.full#ref-list-1 Why The JI? Submit online. http://www.jimmunol.org/ • Rapid Reviews! 30 days* from submission to initial decision • No Triage! Every submission reviewed by practicing scientists • Fast Publication! 4 weeks from acceptance to publication *average by guest on September 25, 2021 Subscription Information about subscribing to The Journal of Immunology is online at: http://jimmunol.org/subscription Permissions Submit copyright permission requests at: http://www.aai.org/About/Publications/JI/copyright.html Email Alerts Receive free email-alerts when new articles cite this article. Sign up at: http://jimmunol.org/alerts The Journal of Immunology is published twice each month by The American Association of Immunologists, Inc., 1451 Rockville Pike, Suite 650, Rockville, MD 20852 Copyright © 2001 by The American Association of Immunologists All rights reserved. Print ISSN: 0022-1767 Online ISSN: 1550-6606. Brain Dendritic Cells and Macrophages/Microglia in Central Nervous System Inflammation1 Hans-Georg Fischer2 and Gaby Reichmann Microglia subpopulations were studied in mouse experimental autoimmune encephalomyelitis and toxoplasmic encephalitis. CNS .inflammation was associated with the proliferation of CD11b؉ brain cells that exhibited the dendritic cell (DC) marker CD11c These cells constituted up to 30% of the total CD11b؉ brain cell population. -

Mixed Electrical–Chemical Synapses in Adult Rat Hippocampus Are Primarily Glutamatergic and Coupled by Connexin-36

ORIGINAL RESEARCH ARTICLE published: 15 May 2012 NEUROANATOMY doi: 10.3389/fnana.2012.00013 Mixed electrical–chemical synapses in adult rat hippocampus are primarily glutamatergic and coupled by connexin-36 Farid Hamzei-Sichani 1,2,3‡, Kimberly G. V. Davidson4‡,ThomasYasumura4,William G. M. Janssen3, Susan L.Wearne 4#, Patrick R. Hof 3, Roger D.Traub 5†, Rafael Gutiérrez 6, Ole P.Ottersen7 and John E. Rash4,8* 1 Department of Neurosurgery, Mount Sinai School of Medicine, New York, NY, USA 2 Program in Neural and Behavioral Science, Downstate Medical Center, State University of New York, Brooklyn, NY, USA 3 Fishberg Department of Neuroscience, Friedman Brain Institute, Mount Sinai School of Medicine, New York, NY, USA 4 Department of Biomedical Sciences, Colorado State University, Fort Collins, CO, USA 5 Department of Physiology and Pharmacology, Downstate Medical Center, State University of New York, Brooklyn, NY, USA 6 Department of Pharmacobiology, Centro de Investigación y Estudios Avanzados del Instituto Politécnico Nacional, México D.F. 7 Centre for Molecular Biology and Neuroscience, University of Oslo, Oslo, Norway 8 Program in Molecular, Cellular, and Integrative Neurosciences, Colorado State University, Fort Collins, CO, USA Edited by: Dendrodendritic electrical signaling via gap junctions is now an accepted feature of neu- Ryuichi Shigemoto, National Institute ronal communication in mammalian brain, whereas axodendritic and axosomatic gap junc- for Physiological Sciences, Japan tions have rarely been described. We present ultrastructural, immunocytochemical, and Reviewed by: Javier DeFelipe, Cajal Institute, Spain dye-coupling evidence for “mixed” (electrical/chemical) synapses on both principal cells Richard J. Weinberg, University of and interneurons in adult rat hippocampus. -

Deconstructing Spinal Interneurons, One Cell Type at a Time Mariano Ignacio Gabitto

Deconstructing spinal interneurons, one cell type at a time Mariano Ignacio Gabitto Submitted in partial fulfillment of the requirements for the degree of Doctor of Philosophy under the Executive Committee of the Graduate School of Arts and Sciences COLUMBIA UNIVERSITY 2016 © 2016 Mariano Ignacio Gabitto All rights reserved ABSTRACT Deconstructing spinal interneurons, one cell type at a time Mariano Ignacio Gabitto Abstract Documenting the extent of cellular diversity is a critical step in defining the functional organization of the nervous system. In this context, we sought to develop statistical methods capable of revealing underlying cellular diversity given incomplete data sampling - a common problem in biological systems, where complete descriptions of cellular characteristics are rarely available. We devised a sparse Bayesian framework that infers cell type diversity from partial or incomplete transcription factor expression data. This framework appropriately handles estimation uncertainty, can incorporate multiple cellular characteristics, and can be used to optimize experimental design. We applied this framework to characterize a cardinal inhibitory population in the spinal cord. Animals generate movement by engaging spinal circuits that direct precise sequences of muscle contraction, but the identity and organizational logic of local interneurons that lie at the core of these circuits remain unresolved. By using our Sparse Bayesian approach, we showed that V1 interneurons, a major inhibitory population that controls motor output, fractionate into diverse subsets on the basis of the expression of nineteen transcription factors. Transcriptionally defined subsets exhibit highly structured spatial distributions with mediolateral and dorsoventral positional biases. These distinctions in settling position are largely predictive of patterns of input from sensory and motor neurons, arguing that settling position is a determinant of inhibitory microcircuit organization. -

Reactive Stroma in Human Prostate Cancer: Induction of Myofibroblast Phenotype and Extracellular Matrix Remodeling1

2912 Vol. 8, 2912–2923, September 2002 Clinical Cancer Research Reactive Stroma in Human Prostate Cancer: Induction of Myofibroblast Phenotype and Extracellular Matrix Remodeling1 Jennifer A. Tuxhorn, Gustavo E. Ayala, Conclusions: The stromal microenvironment in human Megan J. Smith, Vincent C. Smith, prostate cancer is altered compared with normal stroma and Truong D. Dang, and David R. Rowley2 exhibits features of a wound repair stroma. Reactive stroma is composed of myofibroblasts and fibroblasts stimulated to Departments of Molecular and Cellular Biology [J. A. T., T. D. D., express extracellular matrix components. Reactive stroma D. R. R.] and Pathology [G. E. A., M. J. S., V. C. S.] Baylor College of Medicine, Houston, Texas 77030 appears to be initiated during PIN and evolve with cancer progression to effectively displace the normal fibromuscular stroma. These studies and others suggest that TGF-1isa ABSTRACT candidate regulator of reactive stroma during prostate can- Purpose: Generation of a reactive stroma environment cer progression. occurs in many human cancers and is likely to promote tumorigenesis. However, reactive stroma in human prostate INTRODUCTION cancer has not been defined. We examined stromal cell Activation of the host stromal microenvironment is pre- phenotype and expression of extracellular matrix compo- dicted to be a critical step in adenocarcinoma growth and nents in an effort to define the reactive stroma environ- progression (1–5). Several human cancers have been shown to ment and to determine its ontogeny during prostate cancer induce a stromal reaction or desmoplasia as a component of progression. carcinoma progression. However, the specific mechanisms of Experimental Design: Normal prostate, prostatic intra- stromal cell activation are not known, and the extent to which epithelial neoplasia (PIN), and prostate cancer were exam- stroma regulates the biology of tumorigenesis is not fully un- ined by immunohistochemistry. -

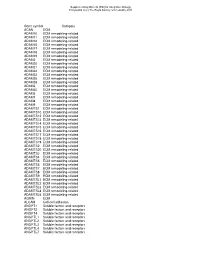

Gene Symbol Category ACAN ECM ADAM10 ECM Remodeling-Related ADAM11 ECM Remodeling-Related ADAM12 ECM Remodeling-Related ADAM15 E

Supplementary Material (ESI) for Integrative Biology This journal is (c) The Royal Society of Chemistry 2010 Gene symbol Category ACAN ECM ADAM10 ECM remodeling-related ADAM11 ECM remodeling-related ADAM12 ECM remodeling-related ADAM15 ECM remodeling-related ADAM17 ECM remodeling-related ADAM18 ECM remodeling-related ADAM19 ECM remodeling-related ADAM2 ECM remodeling-related ADAM20 ECM remodeling-related ADAM21 ECM remodeling-related ADAM22 ECM remodeling-related ADAM23 ECM remodeling-related ADAM28 ECM remodeling-related ADAM29 ECM remodeling-related ADAM3 ECM remodeling-related ADAM30 ECM remodeling-related ADAM5 ECM remodeling-related ADAM7 ECM remodeling-related ADAM8 ECM remodeling-related ADAM9 ECM remodeling-related ADAMTS1 ECM remodeling-related ADAMTS10 ECM remodeling-related ADAMTS12 ECM remodeling-related ADAMTS13 ECM remodeling-related ADAMTS14 ECM remodeling-related ADAMTS15 ECM remodeling-related ADAMTS16 ECM remodeling-related ADAMTS17 ECM remodeling-related ADAMTS18 ECM remodeling-related ADAMTS19 ECM remodeling-related ADAMTS2 ECM remodeling-related ADAMTS20 ECM remodeling-related ADAMTS3 ECM remodeling-related ADAMTS4 ECM remodeling-related ADAMTS5 ECM remodeling-related ADAMTS6 ECM remodeling-related ADAMTS7 ECM remodeling-related ADAMTS8 ECM remodeling-related ADAMTS9 ECM remodeling-related ADAMTSL1 ECM remodeling-related ADAMTSL2 ECM remodeling-related ADAMTSL3 ECM remodeling-related ADAMTSL4 ECM remodeling-related ADAMTSL5 ECM remodeling-related AGRIN ECM ALCAM Cell-cell adhesion ANGPT1 Soluble factors and receptors -

Skeletal Reorganization and Chromatin Accessibility During Re- Vascularization-Based Blastema Regeneration

Preprints (www.preprints.org) | NOT PEER-REVIEWED | Posted: 23 April 2021 doi:10.20944/preprints202104.0642.v1 Article Keratin5-BMP4 mechanosignaling network regulates cell cyto- skeletal reorganization and chromatin accessibility during re- vascularization-based blastema regeneration Xuelong Wang 1,2,4,†, Huiping Guo 1,6,†, Feifei Yu 1,†, Hui Zhang 1, Ying Peng 1, Chenghui Wang 3, Gang Wei 2, Jizhou Yan 1,5,* 1 Department of Developmental Biology, Institute for Marine Biosystem and Neurosciences, Shanghai Ocean University, Shanghai, China. 2 CAS Key Laboratory of Computational Biology, Shanghai Institute of Nutrition and Health, University of Chinese Academy of Sciences, Chinese Academy of Sciences, Shanghai, China 3 Department of Aquaculture, Shanghai Ocean University, Shanghai, China. 4 Present address: Pancreatic Disease Center, Ruijin Hospital, School of Medicine, Shanghai Jiao Tong Univer- sity, Shanghai, China. 5 CellGene Bioscience, Shanghai, China. * Correspondence: [email protected] † These authors contributed equally to this study. Abstract: Heart regeneration after myocardial infarction remains challenging in reconstruction of blood resupply system. Here, we find that in zebrafish heart after resection of the ventricular apex, the local myocardial cells and the clotted blood cells undergo cell remodeling process via cytoplas- mic exocytosis and nuclear reorganization within revascularization-based blastema. The regenera- tive processes are visualized by spatiotemporal expression of three blastema representative factors (alpha-SMA- which marks for fibrogenesis, Flk1for angiogenesis/hematopoiesis, and Pax3a for re- musculogensis),and two histone modifications (H3K9Ac and H3K9Me3 mark for chromatin re- modeling). Using the cultured zebrafish embryonic fibroblasts we identify blastema fraction com- ponents and show that Krt5 peptide could link cytoskeleton network and BMP4 signaling pathway to regulate the transcription and chromatin accessibility at the blastema representative genes and bmp4 genes. -

Evidence for the Nonmuscle Nature of The" Myofibroblast" of Granulation Tissue and Hypertropic Scar. an Immunofluorescence Study

American Journal of Pathology, Vol. 130, No. 2, February 1988 Copyright i American Association of Pathologists Evidencefor the Nonmuscle Nature ofthe "Myofibroblast" ofGranulation Tissue and Hypertropic Scar An Immunofluorescence Study ROBERT J. EDDY, BSc, JANE A. PETRO, MD, From the Department ofAnatomy, the Department ofSurgery, and JAMES J. TOMASEK, PhD Division ofPlastic and Reconstructive Surgery, and the Department of Orthopaedic Surgery, New York Medical College, Valhalla, New York Contraction is an important phenomenon in wound cell-matrix attachment in smooth muscle and non- repair and hypertrophic scarring. Studies indicate that muscle cells, respectively. Myofibroblasts can be iden- wound contraction involves a specialized cell known as tified by their intense staining of actin bundles with the myofibroblast, which has morphologic character- either anti-actin antibody or NBD-phallacidin. Myofi- istics of both smooth muscle and fibroblastic cells. In broblasts in all tissues stained for nonmuscle but not order to better characterize the myofibroblast, the au- smooth muscle myosin. In addition, nonmuscle myo- thors have examined its cytoskeleton and surrounding sin was localized as intracellular fibrils, which suggests extracellular matrix (ECM) in human burn granula- their similarity to stress fibers in cultured fibroblasts. tion tissue, human hypertrophic scar, and rat granula- The ECM around myofibroblasts stains intensely for tion tissue by indirect immunofluorescence. Primary fibronectin but lacks laminin, which suggests that a antibodies used in this study were directed against 1) true basal lamina is not present. The immunocytoche- smooth muscle myosin and 2) nonmuscle myosin, mical findings suggest that the myofibroblast is a spe- components ofthe cytoskeleton in smooth muscle and cialized nonmuscle type of cell, not a smooth muscle nonmuscle cells, respectively, and 3) laminin and 4) cell. -

GDE2 Regulates Subtype-Specific Motor Neuron Generation Through

Neuron Article GDE2 Regulates Subtype-Specific Motor Neuron Generation through Inhibition of Notch Signaling Priyanka Sabharwal,1 Changhee Lee,1 Sungjin Park,1 Meenakshi Rao,1,2 and Shanthini Sockanathan1,* 1The Solomon Snyder Department of Neuroscience, The Johns Hopkins University School of Medicine, PCTB1004, 725 N. Wolfe Street, Baltimore, MD 21205, USA 2Present address: Department of Pediatrics, Children’s Hospital Boston, 300 Longwood Avenue, Boston, MA 02115, USA *Correspondence: [email protected] DOI 10.1016/j.neuron.2011.07.028 SUMMARY which is innervated by specific groups of motor neurons. Indi- vidual motor neuron groups are highly organized in terms of their The specification of spinal interneuron and motor cell body distribution, projection patterns, and function and neuron identities initiates within progenitor cells, consist of force-generating alpha motor neurons that innervate while motor neuron subtype diversification is regu- extrafusal muscle fibers and stretch-sensitive gamma motor lated by hierarchical transcriptional programs imple- neurons that innervate intrafusal muscle fibers of the muscle mented postmitotically. Here we find that mice lack- spindles (Dasen and Jessell, 2009; reviewed in Kanning et al., ing GDE2, a six-transmembrane protein that triggers 2010). The integration of input from both alpha and gamma motor neurons is essential for coordinated motor movement to motor neuron generation, exhibit selective losses occur (Kanning et al., 2010). of distinct motor neuron subtypes, specifically in How is diversity engendered in developing motor neurons? defined subsets of limb-innervating motor pools All motor neurons initially derive from ventral progenitor cells that correlate with the loss of force-generating alpha that are specified to become Olig2+ motor neuron progenitors motor neurons. -

Reduction of Ephrin-A5 Aggravates Disease Progression in Amyotrophic

Rué et al. Acta Neuropathologica Communications (2019) 7:114 https://doi.org/10.1186/s40478-019-0759-6 RESEARCH Open Access Reduction of ephrin-A5 aggravates disease progression in amyotrophic lateral sclerosis Laura Rué1,2 , Patrick Oeckl3, Mieke Timmers1,2, Annette Lenaerts1,2, Jasmijn van der Vos1,2, Silke Smolders1,2, Lindsay Poppe1,2, Antina de Boer1,2, Ludo Van Den Bosch1,2, Philip Van Damme1,2,4, Jochen H. Weishaupt3, Albert C. Ludolph3, Markus Otto3, Wim Robberecht1,4 and Robin Lemmens1,2,4* Abstract Amyotrophic lateral sclerosis (ALS) is a fatal neurodegenerative disease that affects motor neurons in the brainstem, spinal cord and motor cortex. ALS is characterized by genetic and clinical heterogeneity, suggesting the existence of genetic factors that modify the phenotypic expression of the disease. We previously identified the axonal guidance EphA4 receptor, member of the Eph-ephrin system, as an ALS disease-modifying factor. EphA4 genetic inhibition rescued the motor neuron phenotype in zebrafish and a rodent model of ALS. Preventing ligands from binding to the EphA4 receptor also successfully improved disease, suggesting a role for EphA4 ligands in ALS. One particular ligand, ephrin-A5, is upregulated in reactive astrocytes after acute neuronal injury and inhibits axonal regeneration. Moreover, it plays a role during development in the correct pathfinding of motor axons towards their target limb muscles. We hypothesized that a constitutive reduction of ephrin-A5 signalling would benefit disease progression in a rodent model for ALS. We discovered that in the spinal cord of control and symptomatic ALS mice ephrin-A5 was predominantly expressed in neurons. -

Canine Dorsal Root Ganglia Satellite Glial Cells Represent an Exceptional Cell Population with Astrocytic and Oligodendrocytic P

www.nature.com/scientificreports OPEN Canine dorsal root ganglia satellite glial cells represent an exceptional cell population with astrocytic and Received: 17 August 2017 Accepted: 6 October 2017 oligodendrocytic properties Published: xx xx xxxx W. Tongtako1,2, A. Lehmbecker1, Y. Wang1,2, K. Hahn1,2, W. Baumgärtner1,2 & I. Gerhauser 1 Dogs can be used as a translational animal model to close the gap between basic discoveries in rodents and clinical trials in humans. The present study compared the species-specifc properties of satellite glial cells (SGCs) of canine and murine dorsal root ganglia (DRG) in situ and in vitro using light microscopy, electron microscopy, and immunostainings. The in situ expression of CNPase, GFAP, and glutamine synthetase (GS) has also been investigated in simian SGCs. In situ, most canine SGCs (>80%) expressed the neural progenitor cell markers nestin and Sox2. CNPase and GFAP were found in most canine and simian but not murine SGCs. GS was detected in 94% of simian and 71% of murine SGCs, whereas only 44% of canine SGCs expressed GS. In vitro, most canine (>84%) and murine (>96%) SGCs expressed CNPase, whereas GFAP expression was diferentially afected by culture conditions and varied between 10% and 40%. However, GFAP expression was induced by bone morphogenetic protein 4 in SGCs of both species. Interestingly, canine SGCs also stimulated neurite formation of DRG neurons. These fndings indicate that SGCs represent an exceptional, intermediate glial cell population with phenotypical characteristics of oligodendrocytes and astrocytes and might possess intrinsic regenerative capabilities in vivo. Since the discovery of glial cells over a century ago, substantial progress has been made in understanding the origin, development, and function of the diferent types of glial cells in the central nervous system (CNS) and peripheral nervous system (PNS)1.