The Development of Expertise Within a Community of Practice of Scrabble Players

Total Page:16

File Type:pdf, Size:1020Kb

Load more

Recommended publications

-

DOXA Festival 2004

2 table of contents General Festival Information - Tickets, Venues 3 The Documentary Media Society 5 Acknowledgements 6 Partnership Opportunities 7 Greetings 9 Welcome from DOXA 11 Opening Night - The Take 13 Gals of the Great White North: Movies by Canadian Women 14 Inheritance: A Fisherman’s Story 15 Mumbai, India. January, 2004. The World Social Forum. by Arlene Ami 16 Activist Documentaries 18 Personal Politics by Ann Marie Fleming 19 Sherman’s March 20 NFB Master Class with Alanis Obomsawin 21 Festival Schedule 23 Fragments of a Journey in Palestine-Israel 24 Born Into Brothels 25 The Cucumber Incident 26 No Place Called Home 27 Word Wars 29 Trouble in the Image by Alex MacKenzie 30 The Exhibitionists 31 Haack: The King of Techno + Sid Vision 33 A Night Out with the Guys (Reeking of Humanity) 34 Illustrating the Point: The Use of Animation in Documentary 36 Closing Night - Screaming Men 39 Sources 43 3 4 general festival information Tickets Venues Opening Night Fundraising Gala: The Vogue Theatre (VT) 918 Granville Street $20 regular / $10 low income (plus $1.50 venue fee) Pacific Cinémathèque (PC) 1131 Howe Street low income tickets ONLY available at DOXA office (M-F, 10-5pm) All programs take place at Pacific Cinémathèque except Tuesday May Matinee (before 6 pm) screenings: $7 25 - The Take, which is at the Vogue Theatre. Evening (after 6 pm) screenings: $9 Closing Night: $15 screening & reception The Vogue Theatre and Pacific Cinémathèque are Festival Pass: $69 includes closing gala screening & wheelchair accessible. reception (pass excludes Opening Gala) Master Class: Free admission Festival Information www.doxafestival.ca Festival passes are available at Ticketmaster only (pass 604.646.3200 excludes opening night). -

Uncut! First Time In

45833_AFI_AGS 3/30/04 11:38 AM Page 1 THE AMERICAN FILM INSTITUTE GUIDE April 23 - June 13, 2004 ★ TO THEATRE AND MEMBER EVENTS VOLUME 1 • ISSUE 10 AFIPREVIEW UNCUT! FIRST TIME IN DC! GODZILLA!GODZILLA! Plus: Great World War II Films, Filmfest DC, Val Lewton Centennial, Three by Alfred Hitchcock, Natalie Wood Tribute MC5*A TRUE TESTIMONIAL POINT OF ORDER A STREETCAR NAMED DESIRE CITY LIGHTS GODSEND SYLVIA BLOWUP DARK VICTORY SEPARATE BUT EQUAL STORMY WEATHER CAT ON A HOT TIN ROOF WAR AND PEACE PHOTO NEEDED WORD WARS 45833_AFI_AGS 3/30/04 11:39 AM Page 2 Features 2, 3, 4, 7, 13 2 POINT OF ORDER MEMBERS ONLY SPECIAL EVENT! 3 MC5 *A TRUE TESTIMONIAL, GODZILLA GODSEND MEMBERS ONLY 4WORD WARS, CITY LIGHTS ●M ADVANCE SCREENING! 7 KIRIKOU AND THE SORCERESS Wednesday, April 28, 7:30 13 WAR AND PEACE, BLOWUP When an only child, Adam (Cameron Bright), is tragically killed 13 Two by Tennessee Williams—CAT ON A HOT on his eighth birthday, bereaved parents Rebecca Romijn-Stamos TIN ROOF and A STREETCAR NAMED DESIRE and Greg Kinnear are befriended by Robert De Niro—one of Romijn-Stamos’s former teachers and a doctor on the forefront of Filmfest DC 4 genetic research. He offers a unique solution: reverse the laws of nature by cloning their son. The desperate couple agrees to the The Greatest Generation 6-7 experiment, and, for a while, all goes well under 6Featured Showcase—America Celebrates the the doctor’s watchful eye. Greatest Generation, including THE BRIDGE ON The “new” Adam grows THE RIVER KWAI, CASABLANCA, and SAVING into a healthy and happy PRIVATE RYAN young boy—until his Film Series 5, 11, 12, 14 eighth birthday, when things start to go horri- 5 Three by Alfred Hitchcock: NORTH BY bly wrong. -

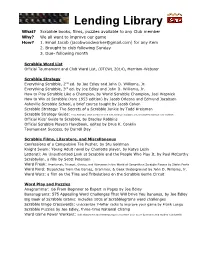

Lending Library

Lending Library What? Scrabble books, films, puzzles available to any Club member Why? We all want to improve our game How? 1. Email Jacob ([email protected]) for any item 2. Brought to club following Sunday 3. Due- following month Scrabble Word List Official Tournament and Club Word List, (OTCWL 2014), Merriam-Webster Scrabble Strategy Everything Scrabble, 2nd ed. by Joe Edley and John D. Williams, Jr. Everything Scrabble, 3rd ed. by Joe Edley and John D. Williams, Jr. How to Play Scrabble Like a Champion, by World Scrabble Champion, Joel Wapnick How to Win at Scrabble (rare 1953 edition) by Jacob Orleans and Edmund Jacobsen Asheville Scrabble School, a brief course taught by Jacob Cohen Scrabble Strategy: The Secrets of a Scrabble Junkie by Todd Kreisman Scrabble Strategy Guide: from Australia; some words not good in N. American Scrabble, yet, the strategy instruction is excellent Official Kids’ Guide to Scrabble, by Bradley Robbins Official Scrabble Players Handbook, edited by Drue K. Conklin Tournament Success, by Darrell Day Scrabble Films, Literature, and Miscellaneous Confessions of a Compulsive Tile Pusher, by Stu Goldman Knight Swam: Young Adult novel by Charlotte player, by Katya Lezin Letterati: An Unauthorized Look at Scrabble and the People Who Play It, by Paul McCarthy Scrabbylon, a film by Scott Petersen Word Freak: Heartbreak, Triumph, Genius, and Obsession in the World of Competitive Scrabble Players by Stefan Fastis Word Nerd: Dispatches from the Games, Grammar, & Geek Underground by John D. Williams, Jr. Word -

Finding Aid to the Sid Sackson Collection, 1867-2003

Brian Sutton-Smith Library and Archives of Play Sid Sackson Collection Finding Aid to the Sid Sackson Collection, 1867-2003 Summary Information Title: Sid Sackson collection Creator: Sid Sackson (primary) ID: 2016.sackson Date: 1867-2003 (inclusive); 1960-1995 (bulk) Extent: 36 linear feet Language: The materials in this collection are primarily in English. There are some instances of additional languages, including German, French, Dutch, Italian, and Spanish; these are denoted in the Contents List section of this finding aid. Abstract: The Sid Sackson collection is a compilation of diaries, correspondence, notes, game descriptions, and publications created or used by Sid Sackson during his lengthy career in the toy and game industry. The bulk of the materials are from between 1960 and 1995. Repository: Brian Sutton-Smith Library and Archives of Play at The Strong One Manhattan Square Rochester, New York 14607 585.263.2700 [email protected] Administrative Information Conditions Governing Use: This collection is open to research use by staff of The Strong and by users of its library and archives. Intellectual property rights to the donated materials are held by the Sackson heirs or assignees. Anyone who would like to develop and publish a game using the ideas found in the papers should contact Ms. Dale Friedman (624 Birch Avenue, River Vale, New Jersey, 07675) for permission. Custodial History: The Strong received the Sid Sackson collection in three separate donations: the first (Object ID 106.604) from Dale Friedman, Sid Sackson’s daughter, in May 2006; the second (Object ID 106.1637) from the Association of Game and Puzzle Collectors (AGPC) in August 2006; and the third (Object ID 115.2647) from Phil and Dale Friedman in October 2015. -

Interruptingmytrainofthought W

editorial input: scott woods and tim powis cover illustration: karen watts foreword: rob sheffield Copyright © 2014 Phil Dellio All rights reserved. No part of this publication may be reproduced or trans- mitted in any form or by any means, electronic or mechanical, including scanning, photocopying, recording or any information storage and retrieval system, without permission in writing from the publisher. Typesetting and layout by Vaughn Dragland ([email protected]) ISBN: 978-1-5010-7319-9 and your mother, and your dad patricia dellio (1932 – 2009) peter dellio (1934 – 2003) contents foreword i introduction iii the publications v show no traces 1 the last phase of yours and yours and mine 31 whole new kinds of weather 49 some place back there 73 rain gray town 105 long journeys wear me out 123 fragments falling everywhere 159 if anything should happen 201 always window shopping 269 constantly aware of all the changes that occur 291 people always live and die in 4/4 time 331 in and around the lake 361 a friend i’ve never seen 415 appendix 435 acknowledgements 437 foreword The first thing I noticed about Phil Dellio was that he sure liked Neil Diamond. The second thing I noticed was that I liked Neil Diamond a lot better after reading what Phil had to say. I was reading a copy of Phil’s fanzine Radio On for the first time, riding a Charlottesville city bus in early 1991, wondering if my mind was playing tricks on me. This guy had provoc- ative comments on recent hits by C&C Music Factory and the KLF; he also wrote about musty 1960s ballads by Herb Alpert or the Vogues. -

WESPA Rules OK AGM Minutes - Page 2

Bimonthly Magazine for the Association of British Scrabble Players Brett wins BMSC for fourth time page 13 WESPA Rules OK AGM Minutes - page 2 Prize Puzzle page 15 Lorraine Feather sings Scrabble page 34 Issue 134 - October 2010 from the editor Well, here I am back in the editor’s chair and already questioning my sanity. Nevertheless, I do have enough of my marbles left to know how much I owe to everybody who has sent me material of some sort for inclusion. I really cannot produce a magazine without you lot, so please do keep giving a thought to what you may contribute. This, of course is issue number 1 of the newsletter under the new title of OnBoard. It was very gratifying to receive so many name suggestions - over 50 - and I am happy with the final choice. The full array of suggestions was emailed to committee members with the request that they send me short lists of their favourites. I had hoped by this means to create my own short list to put to an AGM vote, however the title of OnBoard was the favourite of seven out of the eleven replies I received; and five of those seven declined to add any other names to their list. OnBoard was unchallengeable as the new title. Here is a list of the suggested titles as received by the committee - they were not informed as to who had proposed what. I was pleased to be able to tell them that their popular choice had been solely the suggestion of outgoing editor Elisabeth Jardine. -

February 2012: Vol

N A S P NASPA Bulletin® The monthly news bulletin of the North American SCRABBLE Players Association A February 2012: Vol. 4, No. 1 The Big Easy & Other Points Hither and Yon by Chris Cree Official SCRABBLE tournaments re- turned to the Martin Luther King, Jr. Day weekend west of the Mississippi and did so with a big splash! Lila Crotty (Metairie, LA) and Kate Fu- kawa-Connelly (Kittery, ME) produced the Inaugural Crescent City Cup SCRABBLE Tournament in New Orleans, LA. Their hus- bands, Tim & Tim, handled respectively data entry and direction of the event. The event took place at the Inn on Bourbon, a quaint oasis in the midst of the French Quarter. The room was the perfect size for the event. In a wild finish befitting the personality of this city, 6 people had identical records entering the final round. Jesse Day (Berke- ley, CA) bested Joel Sherman (Bronx, NY) at Table 1 and had enough cumulative point spread to fend off the two others who fin- ished with Jesse’s 14–6 record. The hostess, Alan Mason (Eureka, CA) won the SCRABBLE Flash game at the Redwood Coast SCRABBLE Kate Fukawa-Connelly, finished second and Club’s February 12 tournament in Arcata, CA. The tournament was directed by Leah Kruley. Jim Burlant (Grapevine, TX) finished third. In the Lite Division (with a nod to Port- Member Services 2012 NSC Update land’s description of the second division at an by the Web Committee by John Chew Open), Roy Dixon (Dade City, FL) held off We are often asked if we can provide some As we go to press, we have broken 100 Lindsey Dimmick (Baton Rouge, LA) and sort of information or service to our mem- paid registrants to this year’s National Harry Durbin (Collierville, TN) for the title. -

Pro Vita 2014 Course Listing

Pro Vita 2014 Course Listing ARTS A PERIOD COURSES A CAPPELLA MUSIC JEAN MAHER and LIZA JANE BRANCH ’15 Do you find yourself singing in the car, in the shower, among friends… and even to strangers? Do you watch American Idol or The Voice and think to yourself, I could do that… and win? Ever wonder what it would be like to join a group of like-minded singers, to come together to rehearse and perform current covers from popular music, and leave audiences screaming for more? Then it’s time to sign up for A Cappella Music with Mrs. Maher and Liza Jane! Some singing talent is desired, but no prior formal singing experience is required. We’ll arrange and learn at least three current covers and perform them at the end of the week. INSTALLATION ART PAUL BANEVICIUS Using fabrics, cardboard, wood, plastic, paint, and perhaps even twinkle lights, students will transform the School’s Art Gallery into something new, something unexpected, something magical! With two different periods working on one final project, the groups will collaboratively explore large-scale installation art, work to bring abstract ideas to reality, and tackle the challenges that confront artists as installations expand. The final project will be a giant three-dimensional, multi-sensory sculpture encompassing the entire gallery that completely alters the space—how we perceive it, how we walk through it, and how we experience it. B PERIOD COURSES DEAR DIARY…THE ART OF CREATIVE JOURNALING BRANDI DAHARI Throughout history, many successful artists, leaders, scientists and entrepreneurs have used journals to explore their wildest ideas and make the unimaginable reality. -

INSIDE Cut the Midpeninsula’S Loose Most Complete with Real Estate Listings Kenny and Classified Section Weweekend Eedition K L Y Page 14

Vol. XXV, Number 84 • Friday, July 16, 2004 ■ 50¢ INSIDE Cut The Midpeninsula’s loose most complete with real estate listings Kenny and classified section WeWeekend eEdition k l y Page 14 www.PaloAltoOnline.com Children’s Theatre to stage Disney classics like ‘Aladdin’ Page 8 Eating Out 15 Movie Times 20 Goings On 23 Sports 27 Crossword Puzzle Section 2 ■ Upfront Sea Scout bid rejected by city Page 3 ■ Home & Real Estate Master Gardeners show their stuff Section 2 ■ Upfront Palo Alto police may carry Tasers for ‘safety’ Page 6 Winner of the 2003 Gold Award by Marriott! RESIDENCE INN PALO ALTO–LOS ALTOS. Combining the conveniences of home with the services of a hotel. Guest Suites Feature: Facilities / Services • One or two bedroom suites include fully equipped kitchens with stove, • 156 tastefully appointed suites refrigerator, microwave oven, dishwasher and utensils • Free wireless high-speed Internet access in lobby, meeting rooms & pool areas • Large work desk with desk-level outlets and adjustable lighting • Complimentary buffet breakfast & evening social (Monday-Thursday) •Cable/satellite TV with in-room movies and all-news channel • Manager’s weekly barbecues (summer season) • Granite kitchen countertops and Corian vanities • Dinner delivery service from local restaurants • Coffee maker with complimentary coffee • Express check-out • Separate sleeping and living areas • Complimentary business services (faxing & copying) • Hair dryer, iron and ironing board • Plenty of space for entertaining or meetings • Free high-speed Internet access • Fitness center, Sport Court,® pool and whirlpool Residence Inn by Marriott 4460 El Camino Real Los Altos, California 94022 Reservations: (800) 331-3131 Tel: (650) 559-7890 Fax: (650) 559-7891 www.losaltosresidenceinn.com Page 2 • Wednesday, July 16, 2004 • Palo Alto Weekly UpfrontLocal news, information and analysis rebuffed by the City of Palo Alto. -

Total SCRABBLE®

Total SCRABBLE® The (Un)Official SCRABBLE® Record Book Jan 2009 Update Compiled by Keith W. Smith Page 1 Copyright 2003, 2005, 2009 Keith W. Smith HASBRO is the owner of the registered SCRABBLE® trademark in the United States and Canada. © 2005 HASBRO. All rights reserved. The SCRABBLE® trademark is owned by J.W. Spear and Sons, PLC, a subsidiary of Mattel, Inc. outside of the United States and Canada. Page 2 Acknowledgements This work would not have been possible without the support of the following people who provided information, suggestions and support: Steven Alexander, Paul Avrin, Mike Baron, Lynn Cushman, Bruce D'Ambrosio, Darrell Day, Jan Dixon, Mike Early, Joe Edley, Dave Engelhardt, Paul Epstein, Stefan Fatsis, Mady Garner, Stu Goldman, Bernard Gotlieb, René Gotfryd, John C Green Jr, Ron Hoekstra, Joel Horn, Robert Kahn, Sam Kantimathi, Carol Kaplan, Zev Kaufman, Jim Kramer, John Luebkemann, Joey Mallick, Lloyd Mills, Louie Muller, Philip Nelkon, Rita Norr, Steve Oliger, Jim Pate, Trip Payne, Bryan Pepper, Dan Pratt, Mark Przybyszewski, Mary Rhoades, Ann Sanfedele, Bob Schoenman, Peter Schwartzman, Dee Segrest, Joel Sherman, David Stone, Geoff Thevenot, Graeme Thomas, Ron Tiekert, Susi Tiekert, Joel Wapnick, Dave Wiegand, and Ben Withers. Page 3 A Plea The first thing you need to know about the book you are holding is that it's incomplete. As much as I'd like to have used complete data for every tournament ever played, I just don't have it (and in many cases it may not exist). Future editions will include more complete information and I hope to eventually have complete information. -

Seattle Scrabble® Club Player Information Packet

Seattle SCRABBLE® Club - New Player Information This is an introduction to playing Scrabble® at Club Etiquette: Seattle Club, with a brief overview of the Rules intended to welcome newcomers to club play. Cell phones MUST BE TURNED OFF! Overview: Blue Card or White Card? Official Club name: North American SCRABBLE® Players Seattle Club uses two divisions for pairings. If your average is Association Club #253, Seattle. 365 or higher you must play white card, however blue card players may choose to “play up” into the white card division. Club meets 6pm Tuesdays at University Friends New players usually start with a blue card. Meetinghouse, 4001 9th Ave NE, just northwest of the University Bridge, in Seattle. Word Source We play four games per night, starting about 6:00pm, each Club uses the Official Tournament and Club Word List (OWL) to adjudicate challenges. This is essentially the same as game taking about an hour. You choose your opponent the th first round (new players will be matched appropriately); the the Official Scrabble® Player’s Dictionary 4 Edition (OSPD4), director pairs subsequent rounds based on performance that which is available in most bookstores, except that the OWL night. You can still play the second game if you miss the first also includes about 200 expurgated words, and includes words one as long as you show up before all the cards have been up to 9 letters long (OSPD4 only goes up to 8-letters long). turned in for the first game (no later than 7:00pm, usually). Likewise, you can start with game three or four. -

Playing to Win: Raising Children in a Competitive Culture

“Beautifully written, relentlessly insightful, and methodologically innova- tive, Playing to Win expertly captures the perspectives of parents and children regarding the importance of after- school activities for socializa- tion and childhood in contemporary American society. Hilary Levey Freidman has produced a so cio log i cal gem.” — William A. Corsaro, author of The Sociology of Childhood “Hilary Levey Friedman’s Playing to Win is an essential social science volume that transcends the boundary between scholarship and pop u lar critique. Levey Friedman successfully explains how upper- middle- class Americans think about their children’s engagement in serious leisure: competitive chess, dance competitions, and youth soccer. Listening care- fully to both parents and children, she reveals the tensions and contradic- tions, benefi ts and drawbacks of intense competitions, and provides a perspective necessary for researchers who examine child development and for parents who wish to raise happy, healthy children.” — Gary Alan Fine, author of With the Boys: Little League Baseball and Preadolescent Culture and Gifted Tongues: High School Debate and Adolescent Culture “The world of twenty- fi rst- century childhood has found its superb inter- preter. With sparkling arguments and fascinating evidence, Hilary Levey Friedman’s Playing To Win introduces us to one of America’s most remark- able contemporary innovations: the proliferation of or ga nized, competitive after- school activities. An important contribution to the sociology of culture and inequality.” — Viviana A. Zelizer, author of Pricing the Priceless Child: The Changing Social Value of Children “Hilary Levey Friedman has managed to convince numerous upper- middle- class parents and their children to pause in their mad dash between extracurricular activities to explain why they have chosen this lifestyle.