Invasiveness Ranking System for Non-Native Plants of Alaska

Total Page:16

File Type:pdf, Size:1020Kb

Load more

Recommended publications

-

Caragana Or Siberian Peashrub

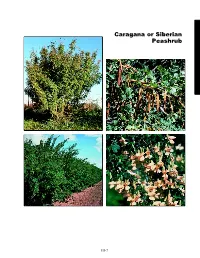

Caragana or Siberian Peashrub slide 5a 400% slide 5b 360% slide 5d slide 5c 360% 360% III-7 Caragana or Environmental Requirements Siberian Peashrub Soils Soil Texture - Adapted to a wide range of soils. (Caragana Soil pH - 5.0 to 8.0. arborescens) Windbreak Suitability Group - 1, 1K, 3, 4, 4C, 5, 6D, 6G, 8, 9C, 9L. General Description Cold Hardiness USDA Zone 2. Drought tolerant legume, long-lived, alkaline-tolerant, tall shrub native to Siberia. Ability to withstand extreme cold Water and dryness. Major windbreak species. Drought tolerant. Does not perform well on very wet or very dry sandy soils. Leaves and Buds Bud Arrangement - Alternate. Light Bud Color - Light brown, chaffy in nature. Full sun. Bud Size - 1/8 inch, weakly imbricate. Leaf Type and Shape - Pinnately-compound, 8 to 12 Uses leaflets per leaf. Conservation/Windbreaks Leaf Margins - Entire. Medium to tall shrub for farmstead and field windbreaks Leaf Surface - Pubescent in early spring, later glabrescent. and highway beautification. Leaf Length - 1½ to 3 inches; leaflets 1/2 to 1 inch. Wildlife Leaf Width - 1 to 2 inches; leaflets 1/3 to 2/3 inch. Used for nesting by several species of songbirds. Food Leaf Color - Light-green, become dark green in summer; source for hummingbirds. yellow fall color. Agroforestry Products Flowers and Fruits No known products. Flower Type - Small, pea-like. Flower Color - Showy yellow in spring. Urban/Recreational Fruit Type - Pod, with multiple seeds. Pods open with a Screening and border, ornamental flowers in spring. popping sound when ripe. Cultivated Varieties Fruit Color - Brown when mature. -

Special Report on ASX-Listed Cannabis and Hemp Stocks

Special Report on ASX-listed Cannabis and Hemp stocks An exciting new sector 24 March 2020 From humble beginnings in Canada around ten years ago the cannabis and hemp industries have blossomed into a major force to be reckoned with by investors the world over. Australia is no exception, with many cannabis and hemp companies having gone live on ASX over the last five years. However, many investors are unfamiliar with the dynamics of this exciting new sector. Pitt Street Research now seeks to close that information gap with our Special Report on Cannabis and Hemp, released 24 March 2020. Welcome to the cannabis and hemp revolution Cannabis and hemp have fuelled a major investment boom since 2014 largely because of the known therapeutic benefits of medicinal cannabis. Governments around the world have responded to the scientific evidence and made it easier for patients to access cannabis-based medicine. Concurrently, voters in many countries have become more favourably disposed towards the legalisation of recreational cannabis. These two trends have fuelled a boom in cannabis, while hemp, from a different plant, had also benefited as investors have moved to use this plant for a variety of purposes, most notably in food. It’s fair to say that cannabis and hemp have quickly become respectable industries worthy of investor attention. Many have come to the view that cannabis and hemp are agents of serious economic change, with potential to seriously disrupt Subscribe to our research HERE sectors as diverse as drinks, building materials and, of course, medicine. Analyst: Stuart Roberts Why should the Canadians have all the fun? Tel: +61 (0)447 247 909 Canada was the origin of the current cannabis and hemp boom because the regulatory framework changed in that [email protected] country around 2013 in a way that allowed entrepreneurs to flourish while the public equity markets allowed large amounts of capital to be raised. -

Japanese Knotweed Fallopia Japonica (Houtt.) R. Decr. Or Polygonum Cuspidatum Sieb

Japanese knotweed Fallopia japonica (Houtt.) R. Decr. or Polygonum cuspidatum Sieb. & Zucc. Giant knotweed Fallopia sachalinensis (F. Schmidt ex Maxim.) R. Decr. or Polygonum sachalinense F. Schmidt ex Maxim. Bohemian knotweed Fallopia × bohemica (Chrtek & Chrtková) J. P. Bailey or Polygonum ×bohemicum (J. Chrtek & Chrtkovß) Zika & Jacobson [cuspidatum ×sachalinense] Family: Polygonaceae Synonyms for Fallopia japonica: Pleuropterus cuspidatus (Sieb. & Zucc.) Moldenke, P. zuccarinii (Small) Small, Polygonum cuspidatum Sieb. & Zucc. var. compactum (Hook. f.) Bailey, P. zuccarinii Small, Reynoutria japonica Houtt. Other common names: Japanese bamboo, fleeceflower, Mexican bamboo Synonyms for Fallopia sachalinensis: Reynoutria sachalinensis (F. Schmidt ex Maxim.) Nakai, Tiniaria sachalinensis (F. Schmidt) Janchen Other common names: none Synonyms for Fallopia x bohemica: none Other common names: none Invasiveness Rank: 87 The invasiveness rank is calculated based on a species’ ecological impacts, biological attributes, distribution, and response to control measures. The ranks are scaled from 0 to 100, with 0 representing a plant that poses no threat to native ecosystems and 100 representing a plant that poses a major threat to native ecosystems. Description Japanese knotweed is a perennial plant that grows from long, creeping rhizomes. Rhizomes are thick, extensive, and 5 to 6 meters long. They store large quantities of carbohydrates. Stems are stout, hollow reddish-brown, swollen at the nodes, and 1 ¼ to 2 ¾ meters tall. Twigs often zigzag slightly from node to node. Leaves are alternate, 5 to 15 cm long, and broadly ovate with more or less truncate bases and acuminate tips. They have short petioles. Plants are dioecious, with male and female flowers on separate plants. Inflorescences are many-flowered, branched, open, and lax. -

Systematics and Evolution of Eleusine Coracana (Gramineae)1

Amer. J. Bot. 71(4): 550-557. 1984. SYSTEMATICS AND EVOLUTION OF ELEUSINE CORACANA (GRAMINEAE)1 J. M. J. de W et,2 K. E. Prasada Rao,3 D. E. Brink,2 and M. H. Mengesha3 departm ent of Agronomy, University of Illinois, 1102 So. Goodwin, Urbana, Illinois 61801, and international Crops Research Institute for the Semi-arid Tropics, Patancheru, India ABSTRACT Finger millet (Eleusine coracana (L.) Gaertn. subsp. coracana) is cultivated in eastern and southern Africa and in southern Asia. The closest wild relative of finger millet is E. coracana subsp. africana (Kennedy-O’Byme) H ilu & de Wet. W ild finger m illet (subsp. africana) is native to Africa but was introduced as a weed to the warmer parts of Asia and America. Derivatives of hybrids between subsp. coracana and subsp. africana are companion weeds of the crop in Africa. Cultivated finger millets are divided into five races on the basis of inflorescence mor phology. Race coracana is widely distributed across the range of finger millet cultivation. It is present in the archaeological record o f early African agriculture that m ay date back 5,000 years. Racial evolution took place in Africa. Races vulgaris, elongata., plana, and compacta evolved from race coracana, and were introduced into India some 3,000 years ago. Little independent racial evolution took place in India. E l e u s i n e Gaertn. is predominantly an African tancheru in India, and studied morphologi genus. Six of its nine species are confined to cally. These include 698 accessions from the tropical and subtropical Africa (Phillips, 1972). -

WHO Expert Committee on Drug Dependence Pre-Review ……………

WHO Expert Committee on Drug Dependence Pre-Review …………….. Cannabis plant and cannabis resin Section 5: Epidemiology This report contains the views of an international group of experts, and does not necessarily represent the decisions or the stated policy of the World Health Organization 1 © World Health Organization 2018 All rights reserved. This is an advance copy distributed to the participants of the 40th Expert Committee on Drug Dependence, before it has been formally published by the World Health Organization. The document may not be reviewed, abstracted, quoted, reproduced, transmitted, distributed, translated or adapted, in part or in whole, in any form or by any means without the permission of the World Health Organization. The designations employed and the presentation of the material in this publication do not imply the expression of any opinion whatsoever on the part of the World Health Organization concerning the legal status of any country, territory, city or area or of its authorities, or concerning the delimitation of its frontiers or boundaries. Dotted and dashed lines on maps represent approximate border lines for which there may not yet be full agreement. The mention of specific companies or of certain manufacturers’ products does not imply that they are endorsed or recommended by the World Health Organization in preference to others of a similar nature that are not mentioned. Errors and omissions excepted, the names of proprietary products are distinguished by initial capital letters. The World Health Organization does not warrant that the information contained in this publication is complete and correct and shall not be liable for any damages incurred as a result of its use. -

Cannabis Dictionary

A MEDICAL DICTIONARY, BIBLIOGRAPHY, AND ANNOTATED RESEARCH GUIDE TO INTERNET REFERENCES JAMES N. PARKER, M.D. AND PHILIP M. PARKER, PH.D., EDITORS ii ICON Health Publications ICON Group International, Inc. 4370 La Jolla Village Drive, 4th Floor San Diego, CA 92122 USA Copyright 2003 by ICON Group International, Inc. Copyright 2003 by ICON Group International, Inc. All rights reserved. This book is protected by copyright. No part of it may be reproduced, stored in a retrieval system, or transmitted in any form or by any means, electronic, mechanical, photocopying, recording, or otherwise, without written permission from the publisher. Printed in the United States of America. Last digit indicates print number: 10 9 8 7 6 4 5 3 2 1 Publisher, Health Care: Philip Parker, Ph.D. Editor(s): James Parker, M.D., Philip Parker, Ph.D. Publisher's note: The ideas, procedures, and suggestions contained in this book are not intended for the diagnosis or treatment of a health problem. As new medical or scientific information becomes available from academic and clinical research, recommended treatments and drug therapies may undergo changes. The authors, editors, and publisher have attempted to make the information in this book up to date and accurate in accord with accepted standards at the time of publication. The authors, editors, and publisher are not responsible for errors or omissions or for consequences from application of the book, and make no warranty, expressed or implied, in regard to the contents of this book. Any practice described in this book should be applied by the reader in accordance with professional standards of care used in regard to the unique circumstances that may apply in each situation. -

Legumes of the North-Central States: C

LEGUMES OF THE NORTH-CENTRAL STATES: C-ALEGEAE by Stanley Larson Welsh A Dissertation Submitted, to the Graduate Faculty in Partial Fulfillment of The Requirements for the Degree of DOCTOR OF PHILOSOPHY Major Subject: Systematic Botany Approved: Signature was redacted for privacy. Signature was redacted for privacy. artment Signature was redacted for privacy. Dean of Graduat College Iowa State University Of Science and Technology Ames, Iowa I960 ii TABLE OF CONTENTS Page ACKNOWLEDGMENTS iii INTRODUCTION 1 HISTORICAL ACCOUNT 3 MATERIALS AND METHODS 8 TAXONOMIC AND NOMENCLATURE TREATMENT 13 REFERENCES 158 APPENDIX A 176 APPENDIX B 202 iii ACKNOWLEDGMENTS The writer wishes to express his deep gratitude to Professor Duane Isely for assistance in the selection of the problem and for the con structive criticisms and words of encouragement offered throughout the course of this investigation. Support through the Iowa Agricultural Experiment Station and through the Industrial Science Research Institute made possible the field work required in this problem. Thanks are due to the curators of the many herbaria consulted during this investigation. Special thanks are due the curators of the Missouri Botanical Garden, U. S. National Museum, University of Minnesota, North Dakota Agricultural College, University of South Dakota, University of Nebraska, and University of Michigan. The cooperation of the librarians at Iowa State University is deeply appreciated. Special thanks are due Dr. G. B. Van Schaack of the Missouri Botanical Garden library. His enthusiastic assistance in finding rare botanical volumes has proved invaluable in the preparation of this paper. To the writer's wife, Stella, deepest appreciation is expressed. Her untiring devotion, work, and cooperation have made this work possible. -

State of New York City's Plants 2018

STATE OF NEW YORK CITY’S PLANTS 2018 Daniel Atha & Brian Boom © 2018 The New York Botanical Garden All rights reserved ISBN 978-0-89327-955-4 Center for Conservation Strategy The New York Botanical Garden 2900 Southern Boulevard Bronx, NY 10458 All photos NYBG staff Citation: Atha, D. and B. Boom. 2018. State of New York City’s Plants 2018. Center for Conservation Strategy. The New York Botanical Garden, Bronx, NY. 132 pp. STATE OF NEW YORK CITY’S PLANTS 2018 4 EXECUTIVE SUMMARY 6 INTRODUCTION 10 DOCUMENTING THE CITY’S PLANTS 10 The Flora of New York City 11 Rare Species 14 Focus on Specific Area 16 Botanical Spectacle: Summer Snow 18 CITIZEN SCIENCE 20 THREATS TO THE CITY’S PLANTS 24 NEW YORK STATE PROHIBITED AND REGULATED INVASIVE SPECIES FOUND IN NEW YORK CITY 26 LOOKING AHEAD 27 CONTRIBUTORS AND ACKNOWLEGMENTS 30 LITERATURE CITED 31 APPENDIX Checklist of the Spontaneous Vascular Plants of New York City 32 Ferns and Fern Allies 35 Gymnosperms 36 Nymphaeales and Magnoliids 37 Monocots 67 Dicots 3 EXECUTIVE SUMMARY This report, State of New York City’s Plants 2018, is the first rankings of rare, threatened, endangered, and extinct species of what is envisioned by the Center for Conservation Strategy known from New York City, and based on this compilation of The New York Botanical Garden as annual updates thirteen percent of the City’s flora is imperiled or extinct in New summarizing the status of the spontaneous plant species of the York City. five boroughs of New York City. This year’s report deals with the City’s vascular plants (ferns and fern allies, gymnosperms, We have begun the process of assessing conservation status and flowering plants), but in the future it is planned to phase in at the local level for all species. -

Asclepias Syriaca L.) After a Single Herbicide Treatment in Natural Open Sand Grasslands László Bakacsy* & István Bagi

www.nature.com/scientificreports OPEN Survival and regeneration ability of clonal common milkweed (Asclepias syriaca L.) after a single herbicide treatment in natural open sand grasslands László Bakacsy* & István Bagi Invasive species are a major threat to biodiversity, human health, and economies worldwide. Clonal growth is a common ability of most invasive plants. The clonal common milkweed Asclepias syriaca L. is the most widespread invasive species in Pannonic sand grasslands. Despite of being an invader in disturbed semi-natural vegetation, this plant prefers agricultural felds or plantations. Herbicide treatment could be one of the most cost-efective and efcient methods for controlling the extended stands of milkweed in both agricultural and protected areas. The invasion of milkweed stand was monitored from 2011 to 2017 in a strictly protected UNESCO biosphere reserve in Hungary, and a single herbicide treatment was applied in May 2014. This single treatment was successful only in a short-term but not in a long-term period, as the number of milkweed shoots decreased following herbicide treatment. The herbicide translocation by rhizomatic roots induced the damage of dormant bud banks. The surviving buds developing shoots, growth of the milkweed stand showed a slow regeneration for a longer-term period. We concluded that the successful control of milkweed after herbicide treatment depends on repeated management of treated areas to suppress further spreading during subsequent seasons. Currently, invasive species are a major threat to biodiversity, human health, and economies 1–4. It has been esti- mated that the fght against invasive species and the damage caused by them in European Union accounts for a minimum of 9.6–12.7 billion euros annually, and this amount is expected to rise to 20 billion euros annually1,5–7. -

Pallas's Cat Status Review & Conservation Strategy

ISSN 1027-2992 I Special Issue I N° 13 | Spring 2019 Pallas'sCAT cat Status Reviewnews & Conservation Strategy 02 CATnews is the newsletter of the Cat Specialist Group, Editors: Christine & Urs Breitenmoser a component of the Species Survival Commission SSC of the Co-chairs IUCN/SSC International Union for Conservation of Nature (IUCN). It is pub- Cat Specialist Group lished twice a year, and is available to members and the Friends of KORA, Thunstrasse 31, 3074 Muri, the Cat Group. Switzerland Tel ++41(31) 951 90 20 For joining the Friends of the Cat Group please contact Fax ++41(31) 951 90 40 Christine Breitenmoser at [email protected] <[email protected]> <[email protected]> Original contributions and short notes about wild cats are welcome Send contributions and observations to Associate Editors: Tabea Lanz [email protected]. Guidelines for authors are available at www.catsg.org/catnews This Special Issue of CATnews has been produced with Cover Photo: Camera trap picture of manul in the support from the Taiwan Council of Agriculture's Forestry Bureau, Kotbas Hills, Kazakhstan, 20. July 2016 Fondation Segré, AZA Felid TAG and Zoo Leipzig. (Photo A. Barashkova, I Smelansky, Sibecocenter) Design: barbara surber, werk’sdesign gmbh Layout: Tabea Lanz and Christine Breitenmoser Print: Stämpfli AG, Bern, Switzerland ISSN 1027-2992 © IUCN SSC Cat Specialist Group The designation of the geographical entities in this publication, and the representation of the material, do not imply the expression of any opinion whatsoever on the part of the IUCN concerning the legal status of any country, territory, or area, or its authorities, or concerning the delimitation of its frontiers or boundaries. -

Processing, Nutritional Composition and Health Benefits of Finger Millet

a OSSN 0101-2061 (Print) Food Science and Technology OSSN 1678-457X (Dnline) DDO: https://doi.org/10.1590/fst.25017 Processing, nutritional composition and health benefits of finger millet in sub-saharan Africa Shonisani Eugenia RAMASHOA1*, Tonna Ashim ANYASO1, Eastonce Tend GWATA2, Stephen MEDDDWS-TAYLDR3, Afam Osrael Dbiefuna JODEANO1 Abstract Finger millet (Eleusine coracana) also known as tamba, is a staple cereal grain in some parts of the world with low income population. The grain is characterized by variations in colour (brown, white and light brown cultivars); high concentration of carbohydrates, dietary fibre, phytochemicals and essential amino acids; presence of essential minerals; as well as a gluten-free status. Finger millet (FM) in terms of nutritional composition, ranks higher than other cereal grains, though the grain is extremely neglected and widely underutilized. Nutritional configuration of FM contributes to reduced risk of diabetes mellitus, high blood pressure and gastro-intestinal tract disorder when absorbed in the body. Utilization of the grain therefore involves traditional and other processing methods such as soaking, malting, cooking, fermentation, popping and radiation. These processes are utilised to improve the dietetic and sensory properties of FM and equally assist in the reduction of anti-nutritional and inhibitory activities of phenols, phytic acids and tannins. However, with little research and innovation on FM as compared to conventional cereals, there is the need for further studies on processing methods, nutritional composition, health benefits and valorization with a view to commercialization of FM grains. Keywords: finger millet; nutritional composition; gluten-free; antioxidant properties; traditional processing; value-added products. Practical Application: Effects of processing on nutritional composition, health benefits and valorization of finger millet grains. -

Field Bindweed (Convolvulus Arvensis): “All ” Tied Up

Weed Technology Field bindweed (Convolvulus arvensis): “all ” www.cambridge.org/wet tied up Lynn M. Sosnoskie1 , Bradley D. Hanson2 and Lawrence E. Steckel3 1 2 Intriguing World of Weeds Assistant Professor, School of Integrative Plant Science, Cornell University, Geneva, NY USA; Cooperative Extension Specialist, Department of Plant Science, University of California – Davis, Davis, CA, USA and 3 Cite this article: Sosnoskie LM, Hanson BD, Professor, Department of Plant Sciences, University of Tennessee, Jackson, TN, USA Steckel LE (2020) Field bindweed (Convolvulus arvensis): “all tied up”. Weed Technol. 34: 916–921. doi: 10.1017/wet.2020.61 Received: 22 March 2020 Revised: 2 June 2020 But your snobbiness, unless you persistently root it out like the bindweed it is, sticks by you till your Accepted: 4 June 2020 grave. – George Orwell First published online: 16 July 2020 The real danger in a garden came from the bindweed. That moved underground, then surfaced and took hold. Associate Editor: Strangling plant after healthy plant. Killing them all, slowly. And for no apparent reason, except that it was Jason Bond, Mississippi State University nature. – Louise Penny Author for correspondence: Lynn M. Sosnoskie, Cornell University, 635 W. Introduction North Avenue, Geneva, NY 14456. (Email: [email protected]) Field bindweed (Convolvulus arvensis L.) is a perennial vine in the Convolvulaceae, or morning- glory family, which includes approximately 50 to 60 genera and more than 1,500 species (Preston 2012a; Stefanovic et al. 2003). The family is in the order Solanales and is characterized by alternate leaves (when present) and bisexual flowers that are 5-lobed, folded/pleated in the bud, and trumpet-shaped when emerged (Preston 2012a; Stefanovic et al.