Public Participation in Plant-Pollinator Conservation: Key Assessment Areas That Support Networked Restoration and Monitoring

Total Page:16

File Type:pdf, Size:1020Kb

Load more

Recommended publications

-

Inthesecondyearofelementarysch

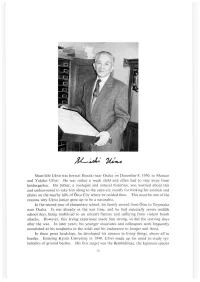

一' Shun-lobi UENo wasbornat Ibaraki near Osaka on December、 l930, 8 to Masuzo and Yu ki ko UENo. He was rather a weak child and often had to stayaway from kindergarten. His father, a zoologist and natural historian, wasworriedabout this andendeavouredto takehimalongto theopenair,mostly for lookingforanimalsand plantsonthenearbyhillsofOtsuCitywhereheresidedthen.This must be one o f the reasonswhyUENojuniorgrewuptobea naturalist. Inthesecondyearofelementaryschool、 hisfamilymovedfromOtsutoToyonaka near Osaka. It was already in the war time, and he had especially severemiddle school days, being mobilized to an aircra「 t factory and suffering from violentbomb att acks. However、 this tryingexperiencemadehimstrong,sodid thestarvingdays after the war. In later years、 his younger associatesand colleagueswerefrequently astonishedat his toughnessin thewildsand hisendurance to hunger andthirst. In thesegreat hardships、 hedeveloped his interest in living things, aboveall in beetles. Entering Kyoto University in 1949, UENo made up his mind tostudy sys- tematicsof groundbeetles. His first target was theBembidiinae theJapanesespecies of whichwereneatly revised ina modern waywithin threeyears.He was, however, intrigued with eyelessspeciesliving in caves, and began to explore cavesby himself. With thesuccessof hisearly collectingsunder theearth, hefell intoabottomlessway. He was absorbed in researches of the cave fauna, which wasalmost unknown before histime.1earnedeverythingnecessary for caving, and eventually becametheonly pro- fessional biospeo1ogist -

Ichneumonidae (Hymenoptera) As Biological Control Agents of Pests

Ichneumonidae (Hymenoptera) As Biological Control Agents Of Pests A Bibliography Hassan Ghahari Department of Entomology, Islamic Azad University, Science & Research Campus, P. O. Box 14515/775, Tehran – Iran; [email protected] Preface The Ichneumonidae is one of the most species rich families of all organisms with an estimated 60000 species in the world (Townes, 1969). Even so, many authorities regard this figure as an underestimate! (Gauld, 1991). An estimated 12100 species of Ichneumonidae occur in the Afrotropical region (Africa south of the Sahara and including Madagascar) (Townes & Townes, 1973), of which only 1927 have been described (Yu, 1998). This means that roughly 16% of the afrotropical ichneumonids are known to science! These species comprise 338 genera. The family Ichneumonidae is currently split into 37 subfamilies (including, Acaenitinae; Adelognathinae; Agriotypinae; Alomyinae; Anomaloninae; Banchinae; Brachycyrtinae; Campopleginae; Collyrinae; Cremastinae; Cryptinae; Ctenopelmatinae; 1 Diplazontinae; Eucerotinae; Ichneumoninae; Labeninae; Lycorininae; Mesochorinae; Metopiinae; Microleptinae; Neorhacodinae; Ophioninae; Orthopelmatinae; Orthocentrinae; Oxytorinae; Paxylomatinae; Phrudinae; Phygadeuontinae; Pimplinae; Rhyssinae; Stilbopinae; Tersilochinae; Tryphoninae; Xoridinae) (Yu, 1998). The Ichneumonidae, along with other groups of parasitic Hymenoptera, are supposedly no more species rich in the tropics than in the Northern Hemisphere temperate regions (Owen & Owen, 1974; Janzen, 1981; Janzen & Pond, 1975), although -

C:\Users\Luca\Documents\Costanza

UNIVERSITÀ DEGLI STUDI DI TRIESTE XXIX CICLO DEL DOTTORATO DI RICERCA IN AMBIENTE E VITA REGIONE FVG – FONDO SOCIALE EUROPEO LA NEOFITIZZAZIONE DEGLI HABITAT E LA SUA RIPERCUSSIONE SULLE COMPONENTI VEGETALI E SULL’ENTOMOF$UNA DEL CARSO DINARICO ITALIANO Settore scientifico-disciplinare: BIO/03 Botanica ambientale e applicata DOTTORANDA COSTANZA UBONI COORDINATORE PROF. GIORGIO ALBERTI SUPERVISORE DI TESI DOTT.SSA MIRIS CASTELLO ANNO ACCADEMICO 2016/2017 Index General Introduction 2 Study area 15 Checklist of the species 16 Chapter 1 20 Chapter 2 37 Chapter 3 58 Chapter 4 97 General Conclusion 117 Appendix 1 – Ongoing projects 119 Appendix 2 – Collaboration with the University of Florence 141 Appendix 3 – Manuscript in preparation 145 Appendix 4 – Accepted Manuscript 152 Appendix 5 – Submitted, in review and published Manuscripts 162 1 General Introduction Colonization is a worldwide phenomenon considering the occupation of an habitat or a territory by a biological community, or the occupation of an ecological niche by a single population of a species (Onofri, 2011). Species can naturally colonize novel environments or they can expand their range, due to anthropogenic disturbances, into regions where they were not historically present. Moreover, human-mediated transport and human-activity allow more individuals and more species to reach new locations, more often and more quickly, ultimately resulting in colonization rates being greater than natural colonization (Blackburn et al., 2014; Hoffmann & Courchamp, 2016). These species, the so called exotic species (Sax, 2002a,b) or non-native species (Hejda et al., 2009), necessarily go through the same stages of introduction, establishment and spread of native species (Hoffmann & Courchamp, 2016). -

Coleoptera: Carabidae) Dinarskog Krša

Ekologija i biogeografija odabranih endemskih epigejskih vrsta trčaka (Coleoptera: Carabidae) dinarskog krša Jambrošić Vladić, Željka Doctoral thesis / Disertacija 2020 Degree Grantor / Ustanova koja je dodijelila akademski / stručni stupanj: University of Zagreb, Faculty of Science / Sveučilište u Zagrebu, Prirodoslovno-matematički fakultet Permanent link / Trajna poveznica: https://urn.nsk.hr/urn:nbn:hr:217:066658 Rights / Prava: In copyright Download date / Datum preuzimanja: 2021-10-04 Repository / Repozitorij: Repository of Faculty of Science - University of Zagreb PRIRODOSLOVNO-MATEMATIČKI FAKULTET BIOLOŠKI ODSJEK Željka Jambrošić Vladić EKOLOGIJA I BIOGEOGRAFIJA ODABRANIH ENDEMSKIH EPIGEJSKIH VRSTA TRČAKA (COLEOPTERA: CARABIDAE) DINARSKOG KRŠA DOKTORSKI RAD Zagreb, 2020. PRIRODOSLOVNO-MATEMATIČKI FAKULTET BIOLOŠKI ODSJEK Željka Jambrošić Vladić EKOLOGIJA I BIOGEOGRAFIJA ODABRANIH ENDEMSKIH EPIGEJSKIH VRSTA TRČAKA (COLEOPTERA: CARABIDAE) DINARSKOG KRŠA DOKTORSKI RAD Zagreb, 2020. FACULTY OF SCIENCE DIVISION OF BIOLOGY Željka Jambrošić Vladić ECOLOGY AND BIOGEOGRAPHY OF SEVERAL ENDEMIC EPIGEIC GROUND BEETLES (COLEOPTERA: CARABIDAE) FROM DINARIC KARST DOCTORAL THESIS Zagreb, 2020. Ovaj je doktorski rad izrađen na Zoologijskom zavodu Prirodoslovno-matematičkog fakulteta Sveučilišta u Zagrebu, pod vodstvom dr. sc. Lucije Šerić Jelaska, u sklopu Sveučilišnog poslijediplomskog doktorskog studija Biologije pri Biološkom odsjeku Prirodoslovno- matematičkog fakulteta Sveučilišta u Zagrebu. III ZAHVALA Iskreno hvala mojoj mentorici dr. sc. -

Nhbs Annual New and Forthcoming Titles Issue: 2006 Complete January 2007 [email protected] +44 (0)1803 865913

nhbs annual new and forthcoming titles Issue: 2006 complete January 2007 www.nhbs.com [email protected] +44 (0)1803 865913 The NHBS Monthly Catalogue in a complete yearly edition Zoology: Mammals Birds Welcome to the Complete 2006 edition of the NHBS Monthly Catalogue, the ultimate buyer's guide to new and forthcoming titles in natural history, conservation and the Reptiles & Amphibians environment. With 300-400 new titles sourced every month from publishers and Fishes research organisations around the world, the catalogue provides key bibliographic data Invertebrates plus convenient hyperlinks to more complete information and nhbs.com online Palaeontology shopping - an invaluable resource. Each month's catalogue is sent out as an HTML Marine & Freshwater Biology email to registered subscribers (a plain text version is available on request). It is also General Natural History available online, and offered as a PDF download. Regional & Travel Please see our info page for more details, also our standard terms and conditions. Botany & Plant Science Prices are correct at the time of publication, please check www.nhbs.com for the latest Animal & General Biology prices. Evolutionary Biology Ecology Habitats & Ecosystems Conservation & Biodiversity Environmental Science Physical Sciences Sustainable Development Data Analysis Reference Mammals Go to subject web page The Abundant Herds: A Celebration of the Sanga-Nguni Cattle 144 pages | Col & b/w illus | Fernwood M Poland, D Hammond-Tooke and L Voigt Hbk | 2004 | 1874950695 | #146430A | A book that contributes to the recording and understanding of a significant aspect of South £34.99 Add to basket Africa's cultural heritage. It is a title about human creativity. -

Scope: Munis Entomology & Zoology Publishes a Wide Variety of Papers

____________ Mun. Ent. Zool. Vol. 10, No. 1, January 2015___________ I This volume is dedicated to the lovely memory of the chief-editor Hüseyin Özdikmen’s khoja ŞA’BAN-I VELİ MUNIS ENTOMOLOGY & ZOOLOGY Ankara / Turkey II ____________ Mun. Ent. Zool. Vol. 10, No. 1, January 2015___________ Scope: Munis Entomology & Zoology publishes a wide variety of papers on all aspects of Entomology and Zoology from all of the world, including mainly studies on systematics, taxonomy, nomenclature, fauna, biogeography, biodiversity, ecology, morphology, behavior, conservation, paleobiology and other aspects are appropriate topics for papers submitted to Munis Entomology & Zoology. Submission of Manuscripts: Works published or under consideration elsewhere (including on the internet) will not be accepted. At first submission, one double spaced hard copy (text and tables) with figures (may not be original) must be sent to the Editors, Dr. Hüseyin Özdikmen for publication in MEZ. All manuscripts should be submitted as Word file or PDF file in an e-mail attachment. If electronic submission is not possible due to limitations of electronic space at the sending or receiving ends, unavailability of e-mail, etc., we will accept “hard” versions, in triplicate, accompanied by an electronic version stored in a floppy disk, a CD-ROM. Review Process: When submitting manuscripts, all authors provides the name, of at least three qualified experts (they also provide their address, subject fields and e-mails). Then, the editors send to experts to review the papers. The review process should normally be completed within 45-60 days. After reviewing papers by reviwers: Rejected papers are discarded. For accepted papers, authors are asked to modify their papers according to suggestions of the reviewers and editors. -

2015 Rhode Island Wildlife Action Plan

Rhode Island Wildlife Action Plan Appendices 1a, 1b, 1c, 1d, 1e, 1f RI WILDLIFE ACTION PLAN: APPENDICES 1a, 1b, 1c, 1d, 1e, 1f Table of Contents Appendix 1a. Rhode Island SWAP Data Sources ........................................................................................ 1 Appendix 1b. Rhode Island Species of Greatest Conservation Need ........................................................ 30 Appendix 1c. Regional Conservation Needs-Species of Greatest Conservation Need ............................. 50 Appendix 1d. List of Rare Plants in Rhode Island ...................................................................................... 62 Appendix 1e: Summary of Rhode Island Vertebrate Additions and Deletions to 2005 SGCN List ............ 74 Appendix 1f: Summary of Rhode Island Invertebrate Additions and Deletions to 2005 SGCN List ........... 77 APPENDIX 1a: RHODE ISLAND WAP DATA SOURCES Appendix 1a. Rhode Island SWAP Data Sources This appendix lists the information sources that were researched, compiled, and reviewed in order to best determine and present the status of the full array of wildlife and its conservation in Rhode Island (Element 1). A wide diversity of literature and programs was consulted and compiled through extensive research and coordination efforts. Some of these sources are referenced in the Literature Cited section of this document, and the remaining sources are provided here as a resource for users and implementing parties of this document as well as for future revisions. Sources include published and unpublished -

Nhbs Annual New and Forthcoming Titles Issue: 2005 Complete January 2006 [email protected] +44 (0)1803 865913

nhbs annual new and forthcoming titles Issue: 2005 complete January 2006 [email protected] +44 (0)1803 865913 The NHBS Monthly Catalogue in a complete yearly edition Zoology: Mammals Birds Welcome to the Complete 2005 edition of the NHBS Monthly Catalogue, the ultimate Reptiles & Amphibians buyer's guide to new and forthcoming titles in natural history, conservation and the Fishes environment. With 300-400 new titles sourced every month from publishers and research organisations around the world, the catalogue provides key bibliographic data Invertebrates plus convenient hyperlinks to more complete information and nhbs.com online Palaeontology shopping - an invaluable resource. Each month's catalogue is sent out as an HTML Marine & Freshwater Biology email to registered subscribers (a plain text version is available on request). It is also General Natural History available online, and offered as a PDF download. Regional & Travel Please see our info page for more details, also our standard terms and conditions. Botany & Plant Science Prices are correct at the time of publication, please check www.nhbs.com for the Animal & General Biology latest prices. Evolutionary Biology Ecology Habitats & Ecosystems Conservation & Biodiversity Environmental Science Physical Sciences Sustainable Development Data Analysis Reference Mammals Adaptacion Funcional del Jabali: Sus scrofa L. A Un Ecosistema Forestal 159 pages | Figures, diagrams, maps | y a Un Sistema Agrario Intensivo en Aragon CPNA Pbk | 2004 | 8489862257 | #153390A | Juan Herrero £19.95 BUY Book in Spanish on ecology of wild boar in Aragon, Spain. .... African Mole-Rats 2873 pages | 25 b/w photos, figs, tabs | Ecology and Eusociality CUP Nigel C Bennett and Chris G Faulkes Hbk | 2000 | 0521771994 | #081928A | African mole-rats are a unique taxon of subterranean rodents that range in sociality from £45.00 BUY solitary-dwelling species through to two `eusocial' species, the Damaraland ... -

Curriculum Vitae

Wondershare Remove Watermark PDFelement Comprehensive CV Megha N. Parajulee, Ph.D. Professor, Faculty Fellow, and Texas A&M Regents Fellow Texas A&M University AgriLife Research and Extension Center 1102 East Drew Street, Lubbock, TX 79403, USA Ph: (806) 746-6101 (office), (806) 632-3407 (cell); Fax: (806) 746-6528 E-mail: [email protected] I. Education and Training Associate Degree in Agriculture. Tribhuvan University, Institute of Agriculture and Animal Sciences, Kathmandu, Nepal (1979-1982). Top-ranked graduate of the university. B.Sc. (Honors) in Agriculture (Agricultural Economics). Himachal Pradesh Agriculture University, Solan, India (1983-1987; USAID Fellow). Top-ranked/Gold medalist. M.S. Entomology, University of Wisconsin-Madison, Wisconsin, USA (1990-1991). Ph.D. Entomology, University of Wisconsin-Madison, Wisconsin, USA (1991-1994). Texas A&M Advanced Leadership Program (2-year leadership training program), Texas A&M University (2016-2018); Program Executive Member (2018-2020). II. Professional Experience Current Positions Sep 2010-current Professor, Faculty Fellow, and Regents Fellow/Cotton Entomology Program Leader, Texas A&M University Research Center, Lubbock, TX. Mar 2021-current Texas A&M AgriLife Task Force Fellow for International Research and Development, College Station, TX. Jan 2004-current Adjunct Professor/Graduate Faculty, Texas Tech University, Department of Biological Sciences, Lubbock, TX. Sep 2014-current Honorary Professor, Department of Entomology, College of Plant Protection, Nanjing Agricultural University, Nanjing, China. Past Positions and Experiences Jul 1987-Jan 1990 Assistant Lecturer, Department of Entomology, Tribhuvan University, Institute of Agriculture, Rampur, Nepal. Jan 1990-May 1994 Research Assistant, Department of Entomology, UW-Madison, WI. Jun 1994-Jun 1996 Postdoctoral Research Associate, Department of Entomology, Texas A&M University, College Station, TX. -

Birds, Bats and Arthropods in Tropical Agroforestry Landscapes: Functional Diversity, Multitrophic Interactions and Crop Yield

Birds, bats and arthropods in tropical agroforestry landscapes: Functional diversity, multitrophic interactions and crop yield Dissertation zur Erlangung des Doktorgrades der Fakultät für Agrarwissenschaften der Georg-August-Universität Göttingen vorgelegt von Bea Maas geboren in San Francisco (USA) Göttingen, September 2013 D7 Referent: Prof. Dr. Teja Tscharntke Korreferent: Prof. Dr. Stefan Vidal Tag der mündlichen Prüfung: 20. November 2013 Table of Contents Summary ................................................................................................................................. 5 Chapter I .................................................................................................................................... General Introduction ........................................................................................................... 7 Chapter II ................................................................................................................................... Bats and birds increase crop yield in tropical agroforestry landscapes ........................................................................... 21 Chapter III ................................................................................................................................. Avian species identity drives predation success in tropical cacao agroforestry ...................................................................................... 53 Chapter IV ................................................................................................................................ -

Edward B. Stark'

AN ABSTRACT OF THE DISSERTATION OF Joan C. Hagar for the degree of Doctor of Philosophy in Forest Science, presented on October 31, 2003. Title: Functional Relationships among Songbirds, Arthrqpods, and Understory Vegetation in Douglas-fir Forests, Western Oregon. Abstract approved: Signature redacted for privacy. Edward B. Stark' Arthropods are important food resources for birds. Forest management activities can influence shrub-dwelling arthropods by affecting the structure and composition of understory shrub communities. Changes in abundance and species composition of arthropod communities in turn may influence the distribution and abundance of insectivorous birds. I examined relationships among bird abundance, availability of arthropod prey, and composition of understory vegetation in managed and unmanaged Douglas-fir forests in western Oregon. I sampled bird abundance, arthropod intensity in terms of abundance and biomass, and habitat structure in 13 forest stands representing a range of structural conditions. I used fecal analysis to describe the diets of five bird species that forage in the understory of conifer forests, and compared the abundance of food resources for Wilson's warblers among shrub species and silvicultural treatments. I also quantified the foraging patterns of Wilson's warbiers, MacGillivray's warblers, and orange-crowned warblers to determine which shrub species were used for foraging. Variation in deciduous shrub cover provided the best explanation of variation in the abundances of Wilson's warbler, MacGillivray's warbler, and Swainson's thrush among study sites. Stands occupied by Wilson's and MacGillivray's warblers had significantly greater cover of deciduous shrubs than unoccupied stands, and both of these species foraged extensively on these shrubs.