Resurrecting Two Melodramatic Vampires of 1820 Ryan Douglas Whittington

Total Page:16

File Type:pdf, Size:1020Kb

Load more

Recommended publications

-

Darwin Prakash CV July 2021

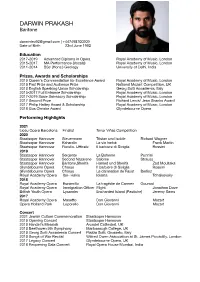

DARWIN PRAKASH Baritone [email protected] | +447498700209 Date of Birth 23rd June 1993 Education 2017-2019 Advanced Diploma in Opera Royal Academy of Music, London 2015-2017 MA Performance (Vocals) Royal Academy of Music, London 2011-2014 BSc (Hons.) Geology University of Delhi, India Prizes, Awards and Scholarships 2019 Queen's Commendation for Excellence Award Royal Academy of Music, London 2019 First Prize and Audience Prize National Mozart Competition, UK 2018 English Speaking Union Scholarship Georg Solti Accademia, Italy 2015-2017 Full Entrance Scholarship Royal Academy of Music, London 2017-2019 Susie Sainsbury Scholarship Royal Academy of Music, London 2017 Second Prize Richard Lewis/ Jean Shanks Award 2017 Philip Hattey Award & Scholarship Royal Academy of Music, London 2016 Gus Christie Award Glyndebourne Opera Performing Highlights 2021 Liceu Opera Barcelona Finalist Tenor Viñas Competition 2020 Staatsoper Hannover Steuermann Tristan und Isolde Richard Wagner Staatsoper Hannover Kaherdin Le vin herbé Frank Martin Staatsoper Hannover Fiorello, Ufficale Il barbiere di Siviglia Rossini 2019 Staatsoper Hannover Sergente La Boheme Puccini Staatsoper Hannover Second Nazarene Salome Strauss Staatsoper Hannover Baritone,Sherifa Hamed und Sherifa Zad Moultaka Glyndebourne Opera Chorus Il barbiere di Siviglia Rossini Glyndebourne Opera Chorus La damnation de Faust Berlioz Royal Academy Opera Ibn- Hakia Iolanta Tchaikovsky 2018 Royal Academy Opera Escamillo La tragédie de Carmen Gounod Royal Academy Opera Immigration Officer Flight Jonathan Dove British Youth Opera Lysander Enchanted Island (Pastiche) Jeremy Sams 2017 Royal Academy Opera Masetto Don Giovanni Mozart Opera Holland Park Leporello Don Giovanni Mozart Concert 2021 Jewish Culture Commemoration Staatsoper Hannover 2019 Opening Concert Staatsoper Hannover 2019 Handel's Messiah Arundel Cathedral, UK 2018 Beethoven 9th Symphony Marlborough College, UK 2018 Georg Solti Accademia Concert Piazza Solti, Grosseto, Italy 2018 Songs of War Recital Wilfred Owen Association at St. -

Advance Program Notes New York Gilbert & Sullivan Players H.M.S

Advance Program Notes New York Gilbert & Sullivan Players H.M.S. Pinafore Friday, May 5, 2017, 7:30 PM These Advance Program Notes are provided online for our patrons who like to read about performances ahead of time. Printed programs will be provided to patrons at the performances. Programs are subject to change. Albert Bergeret, artistic director in H.M.S. Pinafore or The Lass that Loved a Sailor Libretto by Sir William S. Gilbert | Music by Sir Arthur Sullivan First performed at the Opera Comique, London, on May 25, 1878 Directed and conducted by Albert Bergeret Choreography by Bill Fabis Scenic design by Albère | Costume design by Gail Wofford Lighting design by Benjamin Weill Production Stage Manager: Emily C. Rolston* Assistant Stage Manager: Annette Dieli DRAMATIS PERSONAE The Rt. Hon. Sir Joseph Porter, K.C.B. (First Lord of the Admiralty) James Mills* Captain Corcoran (Commanding H.M.S. Pinafore) David Auxier* Ralph Rackstraw (Able Seaman) Daniel Greenwood* Dick Deadeye (Able Seaman) Louis Dall’Ava* Bill Bobstay (Boatswain’s Mate) David Wannen* Bob Becket (Carpenter’s Mate) Jason Whitfield Josephine (The Captain’s Daughter) Kate Bass* Cousin Hebe Victoria Devany* Little Buttercup (Mrs. Cripps, a Portsmouth Bumboat Woman) Angela Christine Smith* Sergeant of Marines Michael Connolly* ENSEMBLE OF SAILORS, FIRST LORD’S SISTERS, COUSINS, AND AUNTS Brooke Collins*, Michael Galante, Merrill Grant*, Andy Herr*, Sarah Hutchison*, Hannah Kurth*, Lance Olds*, Jennifer Piacenti*, Chris-Ian Sanchez*, Cameron Smith, Sarah Caldwell Smith*, Laura Sudduth*, and Matthew Wages* Scene: Quarterdeck of H.M.S. Pinafore *The actors and stage managers employed in this production are members of Actors’ Equity Association, the Union of Professional Actors and Stage Managers in the United States. -

Romantic Textualities, 22

R OMANTICT EXTUALITIES LITERATURE AND PRINT CULTURE, 1780–1840 • ISSN 1748-0116 ◆ ISSUE 22 ◆ SPRING 2017 ◆ SPECIAL ISSUE : FOUR NATIONS FICTION BY WOMEN, 1789–1830 ◆ www.romtext.org.uk ◆ CARDIFF UNIVERSITY PRESS ◆ Romantic Textualities: Literature and Print Culture, 1780–1840, 22 (Spring 2017) Available online at <www.romtext.org.uk/>; archive of record at <https://publications.cardiffuniversitypress.org/index.php/RomText>. Journal DOI: 10.18573/issn.1748-0116 ◆ Issue DOI: 10.18573/n.2017.10148 Romantic Textualities is an open access journal, which means that all content is available without charge to the user or his/her institution. You are allowed to read, download, copy, distribute, print, search or link to the full texts of the articles in this journal without asking prior permission from either the publisher or the author. Unless otherwise noted, the material contained in this journal is licensed under a Creative Commons Attribution-NonCommercial-NoDerivatives 4.0 (cc by-nc-nd) Interna- tional License. See https://creativecommons.org/licenses/by-nc-nd/4.0/ for more information. Origi- nal copyright remains with the contributing author and a citation should be made when the article is quoted, used or referred to in another work. C b n d Romantic Textualities is an imprint of Cardiff University Press, an innovative open-access publisher of academic research, where ‘open-access’ means free for both readers and writers. Find out more about the press at cardiffuniversitypress.org. Editors: Anthony Mandal, Cardiff University Maximiliaan -

Electricity in 19Th Century Medicine and Mary Shelley's Frankenstein

20 January 2011 AUANews CUA Annual Meeting developing medical need. The state- ▼ Continued from page 19 of-the-art facility comprises 10 floors, 209 beds and 5 operating suites. It fea- tures an outpatient clinic, endoscopic across China. simulator training rooms, and urody- While in China the AUA delega- namic simulation and multimedia tion was given a tour of the Urology training rooms as well as sexual edu- Department at Xijing Hospital, Fourth Military Medical University, cation and family planning exhibits by Drs. Yuan Jianlin and Xiaojian for the public. Yang. They also toured the Peking The AUA congratulates the CUA University Wujieping Urology on achieving this significant mile- Medical Center, which opened on stone in its history. To commemo- August 29, 2010 in Beijing (fig. 2). rate the opening of the Wujieping The facility is named after the founder Urology Medical Center, Dr. Lacy of Chinese urology, Dr. Jieping Wu, presented the CUA with an original who worked as a visiting scholar from Fig. 2. AUA delegation tours endoscopic simulation training area at Wujieping Urology Medical Center. William P. Didusch urological draw- 1947 to 1948 at the University of ing. Additional updates regarding Chicago under Dr. Charles B. AUA/CUA collaborations will be Huggins. is continually increasing as the aver- China increases, and the construc- provided in future issues of The clinical demand for urology age life span of the population in tion of this facility responds to this AUANews. ◆ HISTORY Corner Electricity in 19th Century Medicine Electricity, Galvanism and Vitalism gram into animal electricity, which he regarded as a vital force and which was Electricity became a focus of natural soon called “galvanism.” and Mary Shelley’s philosophy in the early modern period. -

UX and Agile: a Bollywood Blockbuster Masala

UX and Agile: A Bollywood blockbuster masala Pradeep Joseph UXD Manager Juniper Networks Bangalore What is Bollywood? Wikipedia says: The name "Bollywood" is derived from Bombay (the former name for Mumbai) and Hollywood, the center of the American film industry. However, unlike Hollywood, Bollywood does not exist as a physical place. Bollywood films are mostly musicals, and are expected to contain catchy music in the form of song-and-dance numbers woven into the script. Indian audiences expect full value for their money. Songs and dances, love triangles, comedy and dare-devil thrills are all mixed up in a three-hour- long extravaganza with an intermission. Such movies are called masala films, after the Hindi word for a spice mixture. Like masalas, these movies are a mixture of many things such as action, comedy, romance and so on. Melodrama and romance are common ingredients to Bollywood films. They frequently employ formulaic ingredients such as star-crossed lovers and angry parents, love triangles, family ties, sacrifice, corrupt politicians, kidnappers, conniving villains, courtesans with hearts of gold, long-lost relatives and siblings separated by fate, dramatic reversals of fortune, and convenient coincidences. What has UX and Agile got to do with Bollywood? As a Designer I faced tremendous challenges while moving into an Agile environment. While drowning the sorrows with designers from other organizations I came to realize that they too face similar challenges. This inspired me to explore further into what makes designers sad, what makes them suck and what are the ways in which they can contribute more in an Agile environment. -

Les Références Antiques Et Modernes Dans Smarra

Francis Claudon Université de Paris XII [email protected] Les Références antiques et modernes dans Smarra Abstract: Charles Nodier is often thought of as belonging to the “Frenetic School”, he is also perceived as an eccentric author, almost as a humorist, which therefore contrasts with the graveness of the major romantic authors, such as Hugo, Novalis or Shelley. Yet, upon taking a closer look, it becomes obvious that Nodier cultivated “horror”, that is a type of romanticism which would later come to be termed “Black Romanticism”. It is also true that this deeply erudite man very skillfully borrowed elements from various sources in order to create a literature of his own, tales which are his, and his only. In this respect, Nodier is an interesting author for comparative studies. Such is the interest of Smarra, Smarra which initially seems to be an imitation of Apuleius. Yet, when studying the antique text closely, it appears that the Latin author really screens another reference, Shakespeare, the allusions to whom are numerous and difficult to decrypt. The result, a juxtaposition of antiquity and modernity, creates a specific coloring, itself reminiscent of the work of the painter Füssli, who also adapted freely Shakespearian sources, adding to them a sort of neoclassic halo. The true charm of Smarra resides there; Nodier is neither an eccentric nor an amateur, his romanticism is very educated and situates him midway between the erudition of the Enlightenment and the illumination of Romanticism. Keywords: freneticism, influences, Shakespeare, Antiquity, painting. Résumé: On range volontiers Charles Nodier parmi les membres de l’école frénétique ; on le tient aussi pour un auteur fantaisiste, voire humoriste, qui trancherait donc avec le sérieux des « grands » romantiques (Hugo, Novalis, Shelley). -

The Power of the Imagination~ Fall 2012 Division of Humanities—English University of Maine at Farmington

English 345 ~ English Romanticism: The Power of the Imagination~ Fall 2012 Division of Humanities—English University of Maine at Farmington Instructor: Dr. Misty Krueger Office: 216A Roberts Learning Center Office Hours: Tuesdays and Thursdays from 10 a.m.-11 a.m. and 2:30 p.m.-3:30 p.m. Office Phone: 207-778-7473 E-mail: [email protected] (preferred method of contact) COURSE DESCRIPTION Welcome to this course, which will cover the English Romantic period (1785-1832). Notable writers from this period include Mary Wollstonecraft, Jane Austen, William Blake, William Wordsworth, Samuel Taylor Coleridge, Lord Byron, the Shelleys, and John Keats, among many others. In this course we will explore how their works react to important contemporary political events, reconstruct a gothic past, draw on the supernatural, and incorporate spontaneity and imagination. Our specific goal in this course is to study how the ‘powers of the imagination’ lead some of the most well-known Romantic authors to craft brilliant and inventive essays, fiction, poetry, and dramatic literature. As such, we will spend our time examining these authors’ inspirations for writing, means of composition, and conceptions of the purpose of literature, as well as its effects on the individual and society-at-large. We are about to study some of the most beautiful literature ever written in the English language. Get ready to be inspired! Get ready to become an enthusiastic, active participant in this course by contributing discussion questions about our readings, completing reading responses, giving a formal class presentation on scholarly criticism, and conversing informally with your classmates about our course materials. -

Rosemary Ellen Guiley

vamps_fm[fof]_final pass 2/2/09 10:06 AM Page i The Encyclopedia of VAMPIRES, WEREWOLVES, and OTHER MONSTERS vamps_fm[fof]_final pass 2/2/09 10:06 AM Page ii The Encyclopedia of VAMPIRES, WEREWOLVES, and OTHER MONSTERS Rosemary Ellen Guiley FOREWORD BY Jeanne Keyes Youngson, President and Founder of the Vampire Empire The Encyclopedia of Vampires, Werewolves, and Other Monsters Copyright © 2005 by Visionary Living, Inc. All rights reserved. No part of this book may be reproduced or utilized in any form or by any means, electronic or mechanical, including photocopying, recording, or by any information storage or retrieval systems, without permission in writing from the publisher. For information contact: Facts On File, Inc. 132 West 31st Street New York NY 10001 Library of Congress Cataloging-in-Publication Data Guiley, Rosemary. The encyclopedia of vampires, werewolves, and other monsters / Rosemary Ellen Guiley. p. cm. Includes bibliographical references and index. ISBN 0-8160-4684-0 (hardcover : alk. paper) ISBN 978-1-4381-3001-9 (e-book) 1. Vampires—Encyclopedias. 2. Werewolves—Encyclopedias. 3. Monsters—Encyclopedias. I. Title. BF1556.G86 2004 133.4’23—dc22 2003026592 Facts On File books are available at special discounts when purchased in bulk quantities for businesses, associations, institutions, or sales promotions. Please call our Special Sales Department in New York at (212) 967-8800 or (800) 322-8755. You can find Facts On File on the World Wide Web at http://www.factsonfile.com Printed in the United States of America VB FOF 10 9 8 7 6 5 4 3 2 1 This book is printed on acid-free paper. -

Der Vampyr De Heinrich Marschner

DESCUBRIMIENTOS Der Vampyr de Heinrich Marschner por Carlos Fuentes y Espinosa ay momentos extraordinarios Polidori creó ahí su obra más famosa y trascendente, pues introdujo en un breve cuento de en la historia de la Humanidad horror gótico, por vez primera, una concreción significativa de las creencias folclóricas sobre que, con todo gusto, el vampirismo, dibujando así el prototipo de la concepción que se ha tenido del monstruo uno querría contemplar, desde entonces, al que glorias de la narrativa fantástica como E.T.A. Hoffmann, Edgar Allan dada la importancia de la Poe, Joseph Sheridan Le Fanu, Jules Verne y el ineludible Abraham Stoker aprovecharían y Hproducción que en ellos se generara. ampliarían magistralmente. Sin duda, un momento especial para la literatura fantástica fue aquella reunión En su relato, Polidori presenta al vampiro, Lord Ruthven, como un antihéroe integrado, a de espléndidos escritores en Ginebra, su manera, a la sociedad, y no es difícil identificar la descripción de Lord Byron en él (sin Suiza, a mediados de junio de 1816 (el mencionar que con ese nombre ya una escritora amante de Byron, Caroline Lamb, nombraba “año sin verano”), cuando en la residencia como Lord Ruthven un personaje con las características del escritor). Precisamente por del célebre George Gordon, Lord Byron, eso, por la publicación anónima original, por la notoria emulación de las obras de Byron y a orillas del lago Lemán, departieron el su fama, las primeras ediciones del cuento se atribuyeron a él, aunque con el tiempo y una baronet Percy Bysshe Shelley, notable incómoda cantidad de disputas, terminara por dársele el crédito al verdadero escritor, que poeta y escritor, su futura esposa Mary fuera tío del poeta y pintor inglés Dante Gabriel Rossetti. -

DAL GOLEM ALLA CREATURA DI MARY SHELLEY: FRANKENSTEIN TRA MITO, SCIENZA E LETTERATURA Angela Articoni*

DAL GOLEM ALLA CREATURA DI MARY SHELLEY: FRANKENSTEIN TRA MITO, SCIENZA E LETTERATURA Angela Articoni* Mi concepì. Presi forma come un neonato, non nel suo corpo, ma nel suo cuore, mi sviluppai nella sua immaginazione finché trovai il coraggio di uscire dalla pagina e di entrare nella vostra mente. Lita Jugde1 Abstract: The similarity between Mary Shelley’s Frankenstein and the Golem of Jewish folklore is no mere coincidence. The Golem’s introduction on early nineteenth century German literature – ironically at the hands of two avowed anti˗Semites, Jacob Grimm and Ludwig Achim von Arnim – may have enabled the novelist Mary Shelley to rediscover it. In addition, being aware of the avant˗garde scientific research that was being carried out at the time, Mary Shelley also took inspiration from her many readings to incorporate mythological and theological debates related to science. Keywords: Golem, Frankenstein, Mary Shelley, Scientific discoveries, Gothic literature, Childrenʼs literature. Frankenstein ovvero il Prometeo moderno Il nome Prometeo, in greco Promethéus, significa “colui che riflette prima”, saggezza e intelligenza sono, infatti, le sue doti principali. È un titano di seconda generazione – figlio di Giapeto e di Climene, figlia di Oceano – sempre dalla parte degli uomini, in contrasto con il dio supremo Zeus, del quale rappresenta in un certo senso l’antitesi. Secondo Esiodo – nella * Dottore di ricerca in Scienze dell’Educazione - Università di Foggia. 1 Lita Jugde, Mary e il mostro. Amore e ribellione. Come Mary Shelley creò Frankenstein, trad. it. R. Bernascone, Il Castoro, Milano 2018, p. 7. 69 Teogonia (700 a.C. ca.) – Prometeo creò l’uomo con creta rinvenuta a Panopea, in Beozia, plasmando figure nelle quali Atena inalava la vita2. -

Music and History in Italian Film Melodrama, 1940-2010

Between Soundtrack and Performance: Music and History in Italian Film Melodrama, 1940-2010 By Marina Romani A dissertation submitted in partial satisfaction of the requirements for the degree of Doctor of Philosophy in Italian Studies and the Designated Emphasis in Film Studies in the Graduate Division of the University of California, Berkeley Committee in charge: Professor Barbara Spackman, Chair Professor Mary Ann Smart Professor Linda Williams Professor Mia Fuller Summer 2015 Abstract Between Soundtrack and Performance: Music and History in Italian Film Melodrama, 1940-2010 by Marina Romani Doctor of Philosophy in Italian Studies and the Designated Emphasis in Film Studies University of California, Berkeley Professor Barbara Spackman, Chair Melodrama manifests itself in a variety of forms – as a film and theatre practice, as a discursive category, as a mode of imagination. This dissertation discusses film melodrama in its visual, gestural, and aural manifestations. My focus is on the persistence of melodrama and the traces it leaves on post-World War II Italian cinema: from the Neorealist canon of the 1940s to works that engage with the psychological and physical, private, and collective traumas after the experience of a totalitarian regime (Cavani’s Il portiere di notte, 1974), to postmodern Viscontian experiments set in a 21st-century capitalist society (Guadagnino’s Io sono l’amore, 2009). The aural dimension is fundamental as an opening to the epistemology of each film. I pay particular attention to the presence of operatic music – as evoked directly or through semiotic displacement involving the film’s aesthetic and expressive figures – and I acknowledge the existence of a long legacy of practical and imaginative influences, infiltrations and borrowings between the screen and the operatic stage in the Italian cinematographic tradition. -

Mary Shelley

Mary Shelley Early Life Mary Wollstonecraft Godwin Shelley was born on August 30, 1797, the daughter of two prominent radical thinkers of the Enlightenment. Her mother was the feminist Mary Wollstonecraft, author of A Vindication of the Rights of Woman, and her father was the political philosopher William Godwin, best known for An Inquiry Concerning Political Justice. Unfortunately, Wollstonecraft died just ten days after her daughter’s birth. Mary was raised by her father and stepmother Mary Jane Clairmont. When she was 16 years old, Mary fell in love with the Romantic poet Percy Bysshe Shelley, who visited her father’s house frequently. They eloped to France, as Shelley was already married. They eventually married after two years when Shelley’s wife Harriet committed suicide. The Writing of Frankenstein In the summer of 1816, the Shelleys rented a villa close to that of Lord Byron in Switzerland. The weather was bad (Mary Shelley described it as “wet, ungenial” in her 1831 introduction to Frankenstein), due to a 1815 eruption of a volcano in Indonesia that disrupted weather patterns around the world. Stuck inside much of the time, the company, including Byron, the Shelleys, Mary’s stepsister Claire Clairmont, and Byron’s personal physician John Polidori, entertained themselves with reading stories from Fantasmagoriana, a collection of German ghost stories. Inspired by the stories, the group challenged themselves to write their own ghost stories. The only two to complete their stories were Polidori, who published The Vampyre in 1819, and Mary Shelley, whose Frankenstein went on to become one of the most popular Gothic tales of all time.