Lincoln's Greenback Mill

Total Page:16

File Type:pdf, Size:1020Kb

Load more

Recommended publications

-

Executive Currency P.O

Executive Currency P.O. Box 2 P.O. Box 16690 ERoseville,xec MIu 48066-0002tive CDuluth,ur MNr e55816-0690ncy 1-586-979-3400ExecuP Phone/TextOt Boxi 2v e or C 1-218-310-0090P Ou Boxr 16690r e Phone/Textncy ExeRosevillecuP OMI tBox 480661-218-525-3651i 2v - 0002 e C Duluth, P Ou FaxBox MNr 16690 55816r e-0690n cy 1-586-979-3400 Phone/Text or 1-218-310-0090 Phone/Text Roseville MI 48066-0002 Duluth, MN 55816-0690 1SUMMER-218-525-3651 2018 Fax 1-586-979P-3400 O Box Phone/Text 2 or 1 -P218 O- 310Box- 009016690 Phone/Text SUMMER 2018 Roseville MI 480661-218-0002-525 - 3651 Duluth, Fax MN 55816-0690 1-586-979-3400 Phone/TextSUMMER or 2011-2188 -310-0090 Phone/Text 1-218-525-3651 Fax SUMMER 2018 Please contact the Barts at 1-586-979-3400 phone/text or [email protected] for catalog items 1 – 745. EXECUTIVE CURRENCY TABLE OF CONTENTS – SUMMER 2018 Banknotes for your consideration Page # Banknotes for your consideration Page # Meet the Executive Currency Team 4 Intaglio Impressions 65 – 69 Terms & Conditions/Grading Paper Money 5 F E Spinner Archive 69 – 70 Large Size Type Notes – Demand Notes 6 Titanic 70 – 71 Large Size Type Note – Legal Tender Notes 6 – 11 1943 Copper and 1944 Zinc Pennies 72 – 73 Large Size Type Notes – Silver Certificates 11 – 16 Lunar Assemblage 74 Large Size Type Notes – Treasury Notes 16 – 18 Introduction to Special Serial Number Notes 75 – 77 Large Size Type – Federal Reserve Bank Notes 19 Small Size Type Notes – Ultra Low Serial #s 78 - 88 Large Size Type Notes – Federal Reserve Notes 19 – 20 Small Size Type -

PART FOUR. XVI. FRACTIONAL CURRENCY 3 Cent Notes

174 PART FOUR. XVI. FRACTIONAL CURRENCY The average person is surprised and somewhat incredulous when The obligation on these is as follows, “Exchangeable for United States informed that there is such a thing as a genuine American 50 Cent Notes by any Assistant Treasurer or designated U.S. Depositary in sums not less than bill, or even a 3 cent bill. With the great profusion of change in the five dollars. Receivable in payments of all dues to the U. States less than five pockets and purses of the last few generations, it does indeed seem Dollars.” strange to learn of valid United States paper money of 3, 5, 10, 15, 25 and 50 Cent denominations. Second Issue. October 10, 1863 to February 23, 1867 Yet it was not always so. During the early years of the Civil War, This issue consisted of 5, 10, 25, and 50 Cent notes. The obverses of the banks suspended specie payments, an act which had the effect all denominations have the bust of Washington in a bronze oval of putting a premium on all coins. Under such conditions, coins of frame but each reverse is distinguished by a different color. all denominations were jealously guarded and hoarded and soon all The obligation on this issue differs slightly, and is as follows, “Exchangeable for but disappeared from circulation. United States Notes by the Assistant Treasurers and designated depositaries of the This was an intolerable situation since it became impossible for U.S. in sums not less than three dollars. Receivable in payment of all dues to the merchants to give small change to their customers. -

20 Dollar Notes

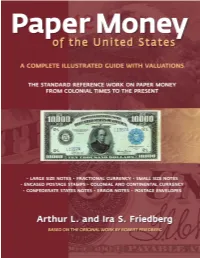

Paper Money of the United States A COMPLETE ILLUSTRATED GUIDE WITH VALUATIONS Twenty-first Edition LARGE SIZE NOTES • FRACTIONAL CURRENCY • SMALL SIZE NOTES • ENCASED POSTAGE STAMPS FROM THE FIRST YEAR OF PAPER MONEY (1861) TO THE PRESENT CONFEDERATE STATES NOTES • COLONIAL AND CONTINENTAL CURRENCY • ERROR NOTES • POSTAGE ENVELOPES The standard reference work on paper money by ARTHUR L. AND IRA S. FRIEDBERG BASED ON THE ORIGINAL WORK BY ROBERT FRIEDBERG (1912-1963) COIN & CURRENCY INSTITUTE 82 Blair Park Road #399, Williston, Vermont 05495 (802) 878-0822 • Fax (802) 536-4787 • E-mail: [email protected] CONTENTS Preface to the Twenty-first Edition 5 General Information on U.S. Currency 6 PART ONE. COLONIAL AND CONTINENTAL CURRENCY I Issues of the Continental Congress (Continental Currency) 11 II Issues of the States (Colonial Currency) 12 PART TWO. TREASURY NOTES OF THE WAR OF 1812 III Treasury Notes of the War of 1812 32 PART THREE. LARGE SIZE NOTES IV Demand Notes 35 V Legal Tender Issues (United States Notes) 37 VI Compound Interest Treasury Notes 59 VII Interest Bearing Notes 62 VIII Refunding Certificates 73 IX Silver Certificates 74 X Treasury or Coin Notes 91 XI National Bank Notes 99 Years of Issue of Charter Numbers 100 The Issues of National Bank Notes by States 101 Notes of the First Charter Period 101 Notes of the Second Charter Period 111 Notes of the Third Charter Period 126 XII Federal Reserve Bank Notes 141 XIII Federal Reserve Notes 148 XIV The National Gold Bank Notes of California 160 XV Gold Certificates 164 PART FOUR. -

Rare & Desirable Works on American Paper Money

Rare & Desirable Works on American Paper Money 141 W. Johnstown Road, Gahanna, Ohio 43230 • (614) 414-0855 • [email protected] Terms of Sale Items listed are available for immediate purchase at the prices indicated. No discounts are applicable. Items should be assumed to be one-of-a-kind and are subject to prior sale. Orders may be placed by post, email, phone or fax. Email or phone are recommended, as orders will be filled on a first-come, first-served basis. Items will be sent via USPS insured mail unless alternate arrangements are made. The cost for deliv- ery will be added to the invoice. There are no additional fees associated with purchases. Lots to be mailed to addresses outside the United States or its Territories will be sent only at the risk of the purchaser. When possible, postal insurance will be obtained. Packages covered by private insur- ance will be so covered at a cost of 1% of total value, to be paid by the buyer. Invoices are due upon receipt. Payment may be made via U.S. check, money order, wire transfer, credit card or PayPal. Bank information will be provided upon request. Unless exempt by law, the buyer will be required to pay 7.5% sales tax on the total purchase price of all lots delivered in Ohio. Purchasers may also be liable for compensating use taxes in other states, which are solely the responsibility of the purchaser. Foreign purchasers may be required to pay duties, fees or taxes in their respective countries, which are also the responsibility of the purchasers. -

V. LEGAL TENDER ISSUES (UNITED STATES NOTES) 1 Dollar Notes

DEMAND NOTES 5 DOLLAR NOTES 36 No. Payable at VG8 F12 No. Payable at VG8 13. Boston Rare 14a. “For the” handwritten Unknown 13a. “For the” handwritten Unknown 15. St. Louis Unknown 14. Cincinnati Unique V. LEGAL TENDER ISSUES (UNITED STATES NOTES) There are five issues of Legal Tender Notes, which are also called Third Issue. These notes are dated March 10, 1863 and were issued United States Notes. in all denominations from 5 to 1,000 Dollars. The obligations, both First Issue. These notes are dated March 10, 1862 and were issued obverse and reverse, are the same as on the notes of the Second in all denominations from 5 to 1,000 Dollars. The obligation on the Obligation of the First Issue. obverse of all these notes is “The United States promise to pay to the bearer...... Fourth Issue. All notes of this issue were printed under authority of Dollars.... Payable at the Treasury of the United States at New York.” There are the Congressional Act of March 3, 1863. The notes issued were from 1 to two separate obligations on the reverse side of these notes. 10,000 Dollars and include the series of 1869, 1874, 1878, 1880, 1907, First Obligation. Earlier issues have the so-called First Obligation 1917 and 1923. The notes of 1869 are titled “Treasury Notes;” all later which reads as follows, “This note is a legal tender for all debts, public and pri- issues are titled “United States Notes.” However, the obligation on all vate. except duties on imports and interest on the public debt, and is exchangeable for series is the same. -

STATEMENT of the PUBLIC DEBT of the UNITED STATES. for the Month of July, 1887

STATEMENT OF THE PUBLIC DEBT OF THE UNITED STATES. For the Month of July, 1887. Iiiterest-beariiijj Debt. AMOUNT OCTSTAXIHNO. AI-TIIOKIZIXG ACT. •d. | Coupon. • 14, '70, and Jan. 20,' 4% per cent Sept. 1, 1891 M., J., S., and D.. $250,000,000 00 $355,595 50 $1,875,000 00 - 14. '70, and Jan. 20, ' 4 per cent July 1, 1907 J., A.. J., andO. 737,804,950 IX) 1,753,970 33 2,459,349 83 runry 26, 1879 4 per cent do 171,900 00 56.727 00 573 00 -23, 1868 3 per cent Jan. and July 14,000,000 00 210,000 00 35,000 00 July 1,1862, and July 2,1864. $2,362,000 matures Jan. 16,1895; $640, OOOinaturesNov. 1,1893; average date of maturity, Mar. 19, 1895; $3,680,000 matures Jan. 1. 1896; 64.320,000 matures Feb. 1, 1896; average date of maturity, Jan. 18, 1896; $9,712,000 matures Jan. 1, 1897; $29,904,932 matures Jan.l, 1898, and 814,004,560 matures Jan. 1, 1899. Aggregate of Interest-bearing Debt j 894,106,062 00 j 158,261,800 00 1,066,600,362 00 | 2.475,613 19 Debt on which Interest lias Ceased since Maturity. Old Debt Various, prior to 1858 1-10 to 6 per cent Matured at various dates prior to January 1, 1861 8151,921 26 862,489 27 Loan of 1847 Jnuuarv 28, 18-17 6 per cent Matured December 31,1867 1,250 00 22 00 Texan Indemnity Stock September 9, 1850 5 percent Matured December 31, 1861 20,000 00 2,945 00 i Loan of 1858 June 14, 1858 5 percent Matured after January 1, 1874 2, IHX) 00 125 00 I Loan of 1860 June 22, 1860 5 per cent Matured January 1,1871 10,000 00 600 00 ! 5-20's of 1862, (called) February 25, 1862 ('. -

Phil the Postage Stamp Chapter 6

The Cover Story Postage and Fractional Currency by Thomas Lera Research Chair, Emeritus -- Smithsonian National Postal Museum By 1862, the U.S. government has issued a lot of paper money to finance the Civil War, yet refused to redeem the currency in coin. This resulted in the initial issue of “Postage Currency” and four subsequent issues of “Fractional Currency.” On July 17, 1862, President Lincoln signed into law a measure proposed by Treasury Secretary Salmon P. Chase, permitting “postage and other stamps of the United States” to be accepted for all dues to the U.S., and redeemable at any “designated depository” in sums less than $5.1 The law prohibited, however, the issue by “any private corporation, banking association, firm, or individual” of any note or token for a sum less than $5. This law was enacted as an alternate to the reduction of the precious metals content in small coins so they would not be hoarded.2 Before the stamps were printed, a decision was made to issue them in a larger, more convenient size, and print them on heavier, ungummed paper. General Francis Spinner, Treasurer of the United States, pasted unused postage stamps on small sheets of Treasury security paper.3 Congress responded to Spinner’s suggestion by authorizing the printing of reproductions of postage stamps on Treasury paper in arrangements patterned after Spinner’s models. In this form, the “stamps” ceased to be stamps and became fractional Government promissory notes, which were not authorized by the initial enabling legislation of July 17, 1862. The notes were issued without legal authorization until passage of the Act of March 3, 1863, provided for their issuance by the Federal Government. -

Currency NOTES

BUREAU OF ENGRAVING AND PRINTING Currency NOTES www.moneyfactory.gov TABLE OF CONTENTS U.S. PAPER CURRENCY – AN OVERVIEW . 1 THE FEDERAL RESERVE SYSTEM ............................. 1 CURRENCY TODAY ..................................... 2 Federal Reserve Notes. 2 PAST CURRENCY ISSUES ................................. 2 Valuation of Currency. 2 Demand Notes . 2 United States Notes. 3 Fractional Currency. 3 Gold Certificates . 4 The Gold Standard. 4 Silver Certificates. 4 Treasury (or Coin) Notes. 5 National Bank Notes. 5 Federal Reserve Bank Notes. 6 PAPER MONEY NOT ISSUED BY THE U.S. GOVERNMENT .............. 7 Celebrity Notes . 7 $3 Notes. 7 Confederate Currency . 7 Platinum Certificates. 7 INTERESTING AND FUN FACTS ABOUT U.S. PAPER CURRENCY . 9 SELECTION OF PORTRAITS APPEARING ON U.S. CURRENCY ............. 9 PORTRAITS AND VIGNETTES USED ON U.S. CURRENCY SINCE 1928 ..................................... 10 PORTRAITS AND VIGNETTES OF WOMEN ON U.S. CURRENCY ............ 10 AFRICAN-AMERICAN SIGNATURES ON U.S. CURRENCY ................ 10 VIGNETTE ON THE BACK OF THE $2 NOTE ....................... 11 VIGNETTE ON THE BACK OF THE $5 NOTE ....................... 11 VIGNETTE ON THE BACK OF THE $10 NOTE ...................... 12 VIGNETTE ON THE BACK OF THE $100 NOTE ..................... 12 ORIGIN OF THE $ SIGN .................................. 12 THE “GREEN” IN GREENBACKS ............................. 12 NATIONAL MOTTO “IN GOD WE TRUST” ........................ 13 THE GREAT SEAL OF THE UNITED STATES ....................... 13 Obverse Side of -

Paying the Postage in the United States, 1776-1921

Paying the Postage in the United States, 1776-1921 Richard C. Frajola, April 2006 Introduction This presentation will examine the relationship between postal rates in the United States and the mode of payment that would have been used to pay those rates and fees between 1776 and 1921. It is an area of study that requires an examination of coins, currency and tokens, as well as stamps and postal history. The coins of Great Britain, Portugal, France, and Spain and their dominions circulated widely in the United States with official sanction, most with legal tender status, until 1857 when such status was withdrawn. The American monetary system was based on the silver content of the Spanish eight-reales coins. The multi-tiered postal rates in effect before 1845 were largely based on the circulating eights of these Spanish dollars rather than on decimal divisions. In 1851 the most-used postal rate was reduced to three cents. The act that reduced the rate also authorized the production of a three-cent coin, now referred to as a trime. This is the first instance of a coin being minted directly to aid in the payment of a postal rate, and a postage stamp, in the United States. The relationship between postage stamps and money that was initiated with the trime led directly to the emergency measures employed during the Civil War in which postage stamps served as money, and culminated with the issuance of fractional currency in 1862. Following the Civil War, until the Specie Resumption Act of 1875 was passed, paper currency was widely used for conducting small transactions, such as the payment of postage. -

Bep History Fact Sheet

BUREAU OF ENGRAVING AND PRINTING DEPARTMENT OF THE TREASURY Prepared by the Historical Resource Center BEP HISTORY FACT SHEET Last Updated Apri l 20 13 FRACTIONAL CURRENCY Fractional Currency notes, of which there are many varieties, denominations, and issues, emerged during the Civil War. Once the war began, the public chose to hold on to coins because of their value as precious metal. The result was fewer coins available for circulation. To remedy the situation, Congress in 1862 authorized the use of postage and other stamps for paying debts to the U.S. government. This created a shortage of postage stamps. To solve this problem, notes in denominations of less than $1 were issued. These notes were known as postage notes because their designs were taken from existing postage stamps. Later issues of such notes in denominations under $1 had designs more in keeping with the appearance of currency notes. These issues were known as Fractional Currency and were authorized in 1863. The Bureau of Engraving and Printing (BEP) was a new department at the time of the first issue of Fractional Currency, and so the currency was produced by two private companies—The American Bank Note Company and the National Bank Note Company. Additional Sources Milton R. Friedberg, The ESIGN EATURES OF RACTIONAL URRENCY Encyclopedia of United States D F F C Fractional and Postal Currency, The first issue of Fractional Currency had no Treasury Department signatures or 1978. seals. With the second issue, the size of all denominations became uniform, the obverse (the face) was printed in black and the reverse (the back) was printed in one Matt Rothert, A Guide Book of of four colors (red, purple, green, or tan). -

Paper Currency Collection of Texas Ranger Hall of Fame

Official State Historical Center of the Texas Rangers law enforcement agency. The Following Article was Originally Published in the Texas Ranger Dispatch Magazine The Texas Ranger Dispatch was published by the Texas Ranger Hall of Fame and Museum from 2000 to 2011. It has been superseded by this online archive of Texas Ranger history. Managing Editors Robert Nieman 2000-2009; (b.1947-d.2009) Byron A. Johnson 2009-2011 Publisher & Website Administrator Byron A. Johnson 2000-2011 Director, Texas Ranger Hall of Fame Technical Editor, Layout, and Design Pam S. Baird Funded in part by grants from the Texas Ranger Association Foundation Copyright 2017, Texas Ranger Hall of Fame and Museum, Waco, TX. All rights reserved. Non-profit personal and educational use only; commercial reprinting, redistribution, reposting or charge-for- access is prohibited. For further information contact: Director, Texas Ranger Hall of Fame and Museum, PO Box 2570, Waco TX 76702-2570. Paper Currency Collection of Texas Ranger Hall of Fame The Paper Currency Collection of the Texas Ranger Hall of Fame and Museum Byron A. Johnson Executive Director, Texas Ranger Hall of Fame and Museum with Christina Stopka Currency Exhibit Curator, Tobin & Anne Armstrong Texas Ranger Research Center Director The Texas Ranger Hall of Fame and Museum would like to thank the Staton family and the citizens of Waco for the donations in this currency collection - a magnificent legacy. It is a window to a different time when paper dollars truly conveyed the strength, ideals, and heritage of a nation. $100 Series 1922 Gold Certificate Catalog # 2000.039.073.115 Gift of the Staton Estate in memory of James A. -

The Colonial Newsletter 6 BREEN, WALTER H

1 1914 Exhibition of United States and The Colonial Coins Reprint 2077 Colonial Newsletter Memorandum of Agreement (ANS/CNL) 1661 Cumulative Index AMERICAN PLANTATIONS TOKENS of JAMES II 1/24 Part Real of 1688. 224 Serial Nos. 1-159 Revised January 27, 2016 ANALYSIS see also X-RAY ANALYSIS Copyright © 2016 by Auction Appearances of The American Numismatic Society, Inc. Massachusetts Coppers (TN-126) 1100 Experimental Die Analysis Chart ========================================== for the Connecticut Coppers 572, 594, 630 In Search of Reuben Harmon’s Section No. 1 Vermont Mint and the Original Mint Site (TN-172 ) 1657 Subject and Author “Quantity Analysis” of Massachusetts ========================================== Cents and Half Cents (TN-113) 1014, 1100 Late Date Analysis of the Section 2 (Illustrations Index) Fairfield Hoard (G-9) 1383 Starts on Page 53 The Usefulness of X-Ray Diffraction in Numismatic Analysis. (TN-121) 1075 Section 3 (Conversion Chart) Weight Histograms of Fugio Cents and Starts on Page 65 Virginia Halfpence 1053 The Appleton-Massachusetts Historical Society Rhode Island =================== A =================== Ship Token with Vlugtende - - (Were There Three [or More] Rhode Island Ship Tokens with ABERCROMBY, _____________ Vlugtende on the Obverse?) 1128 Father-in-law of John Hinkley Mitchell. 419 X-Ray Fluorescence Spectroscopy 1803 ADAMS, EDGAR H. ANNOTATED CNL Numismatic researcher & collector; Our Next Decade 306 his notebooks at ANS. 255, 270 Annotated Betts, The Address by Wyllys Betts, Esq. ADAMS, EVA “Counterfeit Half Pence Current ex-Director of the U.S.Mint 315, 319, 332 the American Colonies.” April 1886. (17 pages + i) 747 ADAMS, JOHN W. 1693 Indian Peace Medal 1507 ANNOTATED HALFPENNY Garrett Collection at The Adventures of a Halfpenny; Commonly Johns Hopkins University (TN-40) 435 called a Birmingham Halfpenny, Original Manuscript of “The or Counterfeit; as related by Earliest New York Token” for itself.