Paying the Postage in the United States, 1776-1921

Total Page:16

File Type:pdf, Size:1020Kb

Load more

Recommended publications

-

PCGS Certifies 1806 $5 Capped Bust Triple Struck Mint Error

TM minterrornews.com PCGS Certifies 1806 $5 Capped Bust Triple Struck Mint Error 18 Page Price Guide Issue 16 • Winter 2006 Inside! A Mike Byers Publication Al’s Coins Dealer in Mint Errors and Currency Errors alscoins.com pecializing in Mint Errors and Currency S Errors for 25 years. Visit my website to see a diverse group of type, modern mint and major currency errors. We also handle regular U.S. and World coins. I’m a member of CONECA and the American Numismatic Association. I deal with major Mint Error Dealers and have an excellent standing with eBay. Check out my show schedule to see which major shows I will be attending. I solicit want lists and will locate the Mint Errors of your dreams. Al’s Coins P.O. Box 147 National City, CA 91951-0147 Phone: (619) 442-3728 Fax: (619) 442-3693 e-mail: [email protected] Mint Error News Magazine Issue 16 • W i n t e r 2 0 0 6 Issue 16 • Winter 2006 Publisher & Editor - Table of Contents - Mike Byers Design & Layout Mike Byers’ Welcome 4 Sam Rhazi Off-Center Errors 5 Off-Metal & Clad Layer Split-Off Errors 17 Contributing Editors Buffalo 5¢ “Speared Bison” & WI 25¢ “Extra Leaves” 21 Tim Bullard Other Mint Error Types 24 Allan Levy PCGS Certifies 1806 $5 Capped Bust Triple Struck Mint Error 30 Contributing Writers NGC Certifies Double Struck 1873 $20 J-1344 34 Heritage Galleries & Auctioneers John Dannreuther • Mike Diamond Indian Cent Cu-Ni Reverse Die Cap 35 NGC • Rich Schemmer 1863 Indian Cent Reverse Die Cap 36 Bill Snyder • Fred Weinberg A Collection of Off-Metal Mint Errors Surfaces 38 Advertising 1973-S Kennedy Half Dollar Struck on Struck Aluminum Token 46 The ad space is sold out. -

PART FOUR. XVI. FRACTIONAL CURRENCY 3 Cent Notes

174 PART FOUR. XVI. FRACTIONAL CURRENCY The average person is surprised and somewhat incredulous when The obligation on these is as follows, “Exchangeable for United States informed that there is such a thing as a genuine American 50 Cent Notes by any Assistant Treasurer or designated U.S. Depositary in sums not less than bill, or even a 3 cent bill. With the great profusion of change in the five dollars. Receivable in payments of all dues to the U. States less than five pockets and purses of the last few generations, it does indeed seem Dollars.” strange to learn of valid United States paper money of 3, 5, 10, 15, 25 and 50 Cent denominations. Second Issue. October 10, 1863 to February 23, 1867 Yet it was not always so. During the early years of the Civil War, This issue consisted of 5, 10, 25, and 50 Cent notes. The obverses of the banks suspended specie payments, an act which had the effect all denominations have the bust of Washington in a bronze oval of putting a premium on all coins. Under such conditions, coins of frame but each reverse is distinguished by a different color. all denominations were jealously guarded and hoarded and soon all The obligation on this issue differs slightly, and is as follows, “Exchangeable for but disappeared from circulation. United States Notes by the Assistant Treasurers and designated depositaries of the This was an intolerable situation since it became impossible for U.S. in sums not less than three dollars. Receivable in payment of all dues to the merchants to give small change to their customers. -

Benjamin Franklin (10 Vols., New York, 1905- 7), 5:167

The American Aesthetic of Franklin's Visual Creations ENJAMIN FRANKLIN'S VISUAL CREATIONS—his cartoons, designs for flags and paper money, emblems and devices— Breveal an underlying American aesthetic, i.e., an egalitarian and nationalistic impulse. Although these implications may be dis- cerned in a number of his visual creations, I will restrict this essay to four: first, the cartoon of Hercules and the Wagoneer that appeared in Franklin's pamphlet Plain Truth in 1747; second, the flags of the Associator companies of December 1747; third, the cut-snake cartoon of May 1754; and fourth, his designs for the first United States Continental currency in 1775 and 1776. These four devices or groups of devices afford a reasonable basis for generalizations concerning Franklin's visual creations. And since the conclusions shed light upon Franklin's notorious comments comparing the eagle as the emblem of the United States to the turkey ("a much more respectable bird and withal a true original Native of America"),1 I will discuss that opinion in an appendix. My premise (which will only be partially proven during the fol- lowing discussion) is that Franklin was an extraordinarily knowl- edgeable student of visual symbols, devices, and heraldry. Almost all eighteenth-century British and American printers used ornaments and illustrations. Many printers, including Franklin, made their own woodcuts and carefully designed the visual appearance of their broad- sides, newspapers, pamphlets, and books. Franklin's uses of the visual arts are distinguished from those of other colonial printers by his artistic creativity and by his interest in and scholarly knowledge of the general subject. -

Medals & Tokens

AUG. 2018 EXONUMIA & FOREIGN SUPPLEMENT | VALID THRU AUG. 24, 2018 | AVAIL. SUBJECT TO CHANGE Our monthly specials list features series of coins we don’t normally keep in stock, as well as other key date, unique, and rare items. Most items are (1) only unless indicated in ( ), so act fast! Second choice(s) are appreciated. NOTE: We attempt to represent the condition of each coin as accurately as possible; however, due to space limitations we may not be able to include every detail. Prices reflect condition. “In Coins We Trust” | Quality ∙ Service ∙ Value | Since 1986 | PO Box 66, La Habra, CA 90633-0066 | (855) 33-COINS ∙ (855) 332-6467 | www.mcqueeneycoins.com MEDALS & TOKENS CLUBS, CORPS & ORGS (CONT) LOCAL (CITY/CNTY/ST) (CONT) MILITARY / WAR (CONT) PRESIDENT. / POLITICAL (CONT) AND OTHER NOVELTY ITEMS □ 1975 LEBANON VALLEY COIN □ 1975 HIALEAH RACE 50th | 3.00 (2) □ 1991 GENERAL COLIN POWELL □ 1981 PRESIDENTIAL INAUGRA- CLUB, TRAIN STATION | 2.00 □ 1976 BOSTON OLD STATEHOUSE MEDAL | 4.00 TION COIN | 2.00 ADVERTISING □ 1976 FAMILY WEEKLY MAG., BICENTENNIAL | 2.00 □ 1991 MARSHALL ISLANDS $5, □ 1984 THE GREAT SOCIETY, LBJ, □ 1794 FLOWING HAIR CENT, ALA- FREEDOM OF THE PRESS | 1.50 □ 1976 CITIZENS BANK OF DRUM- DESERT STORM | 4.00 TYRANNY NONSENSE | 3.00 BAMA COIN & CURRENCY | 1.00 □ 1976 LEBANON VALLEY COIN WRIGHT, OK 75th | 1.50 □ 1/8th BATTALION JUMPING MUS- □ 1990 EISENHOWER GETTYSBURG □ 1935 PRIMA BREWING COMPA- CLUB, 1st COURTHOUSE | 2.00 □ 1976 OLD NORTH BRIDGE, CON- TANGS (VIETNAM) CHALLENGE FARM, “LAST HOME” | 2.50 NY, “GOOD FOR -

A Picture Gallery of U.S. Colonial Coins and Tokens Prior to the Establishment of the U.S

A picture gallery of U.S. colonial coins and tokens Prior to the establishment of the U.S. Mint in 1792, several of the original colonies and states made their own coins, or in some cases coins or tokens were made elsewhere (usually in Eng- land, Ireland or France) for use in the American colonies. There are also some post-1792 private issues, oen depicng George Washington, that are considered part of the U.S. colonial coin series. For more informaon, see A Guide Book of United States Coins (“Red Book”). Collecng colonial coins is more popular “back east,” but there are a few Pacific Northwest col- lectors who have built collecons of colonials, and there is an annual meeng of the Colonial Coin Collectors Club (C4) at the annual PNNA spring convenon. “The Colonial Era” introducon on the next page was originally wrien for a C4 display at an ANA show in the Northwest. The coins and tokens pictured in this gallery are from a local collecon that was sold, with the excepon that the Fugio Cent was from a different private collecon. Enjoy! Photography by Eric Holcomb. © Eric Holcomb, 2001, 2020. Licensed for private non- commercial use. Coin club and school educaonal use permied and encouraged. Limited edito- rial use by the news media is also permied and encouraged. This material may be used as a reference for commercial transacons, but the actual images may not be sold or used for com- mercial adversing purposes without wrien permission of the copyright owner. THE COLONIAL ERA Coins, Tokens, Medals, and Paper Currency of Early America This is a more general introducƟon to numismaƟc items dated from the 1500’s to 1820 that either circulated in early America (the colonies, or the states prior to the U.S. -

20 Dollar Notes

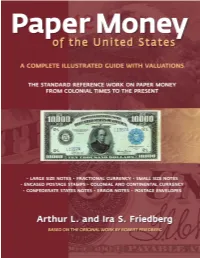

Paper Money of the United States A COMPLETE ILLUSTRATED GUIDE WITH VALUATIONS Twenty-first Edition LARGE SIZE NOTES • FRACTIONAL CURRENCY • SMALL SIZE NOTES • ENCASED POSTAGE STAMPS FROM THE FIRST YEAR OF PAPER MONEY (1861) TO THE PRESENT CONFEDERATE STATES NOTES • COLONIAL AND CONTINENTAL CURRENCY • ERROR NOTES • POSTAGE ENVELOPES The standard reference work on paper money by ARTHUR L. AND IRA S. FRIEDBERG BASED ON THE ORIGINAL WORK BY ROBERT FRIEDBERG (1912-1963) COIN & CURRENCY INSTITUTE 82 Blair Park Road #399, Williston, Vermont 05495 (802) 878-0822 • Fax (802) 536-4787 • E-mail: [email protected] CONTENTS Preface to the Twenty-first Edition 5 General Information on U.S. Currency 6 PART ONE. COLONIAL AND CONTINENTAL CURRENCY I Issues of the Continental Congress (Continental Currency) 11 II Issues of the States (Colonial Currency) 12 PART TWO. TREASURY NOTES OF THE WAR OF 1812 III Treasury Notes of the War of 1812 32 PART THREE. LARGE SIZE NOTES IV Demand Notes 35 V Legal Tender Issues (United States Notes) 37 VI Compound Interest Treasury Notes 59 VII Interest Bearing Notes 62 VIII Refunding Certificates 73 IX Silver Certificates 74 X Treasury or Coin Notes 91 XI National Bank Notes 99 Years of Issue of Charter Numbers 100 The Issues of National Bank Notes by States 101 Notes of the First Charter Period 101 Notes of the Second Charter Period 111 Notes of the Third Charter Period 126 XII Federal Reserve Bank Notes 141 XIII Federal Reserve Notes 148 XIV The National Gold Bank Notes of California 160 XV Gold Certificates 164 PART FOUR. -

Coins and Medals;

CATALOGUE OF A VERY IKTERESTIKG COLLECTION'' OF U N I T E D S T A T E S A N D F O R E I G N C O I N S A N D M E D A L S ; L ALSO, A SMx^LL COLLECTION OF ^JMCIEjMT-^(^REEK AND l^OMAN foiJMg; T H E C A B I N E T O F LYMAN WILDER, ESQ., OF HOOSICK FALLS, N. Y., T O B E S O L D A T A U C T I O N B Y MJSSSBS. BAjYGS . CO., AT THEIR NEW SALESROOMS, A/'os. yjg and ^4.1 Broadway, New York, ON Wednesday, Thursday, Friday and Saturday, May 21, 23 and 2Ji,, 1879, AT HALF PAST TWO O'CLOCK. C a t a l o g u e b y J o l a n W . H a s e l t i n e . PHILADELPHIA: Bavis & Phnnypackeh, Steam Powee Printers, No. 33 S. Tenth St. 1879. j I I I ih 11 lii 111 ill ill 111 111 111 111 11 1 i 1 1 M 1 1 1 t1 1 1 1 1 1 - Ar - i 1 - 1 2 - I J 2 0 - ' a 4 - - a a 3 2 3 B ' 4 - J - 4 - + . i a ! ! ? . s c c n 1 ) 1 1 1 1 1 1 1 1 1 1 1 1 'r r '1' '1' ,|l l|l 1 l-Tp- S t ' A L E O P O n e - S i x t e e n t h o f a n I n c h . -

Colonial Coins

COLONIAL COINS VIRGINIA HALFPENNY NEW YORK COPPER 1783 WASHINGTON DRAPED BUST *1 *5 WITH COLLAR BUTTON 1738, Virginia. Copper. Bust of George III facing 1787, New York. Copper. Bust facing left on *9 right. Extremely Fine. Some corrosion and pitting obverse, seated figure facing left on reverse. A 1783. United States. Scarcer type of this coin with on obverse. Couple of rim problems. A fine inex- nice moderate grade “NOVA EBORAC” with a the button on the drapery at neck. Fine. pensive example. touch of red color. $150 - up $125 - 175 $325 - 375 NEW JERSEY COPPER VERMONT BRITANNIA WASHINGTON LIBERTY & *2 *6 SECURITY PENNY 1788, New Jersey. Copper. Large planchet. Maris 1787, Vermont. Copper. Bust facing right on *10 67-V. Very Good. Horse’s head facing right on obverse, seated figure facing left on reverse. A 1795. Undated Liberty and Security penny. The obverse with the words “NOVA CAESAREA” (New very slight planchet clip at 8 o’clock. A decent rim is marked “An asylum for the oppress’d of All Jersey) . These coins were passed as 15 to a shilling. example in Fine condition with a typically weak Nations”. Near EF. Nice shield detail remains on reverse. Granular sur- reverse. $275 - 325 face. A nice, inexpensive example of an early New $225 - 275 Jersey Copper. $100 - 150 1721 H FRENCH COLONIES A NICE NCG GRADED *11 WASHINGTON LARGE EAGLE COPPER NEW JERSEY COPPER 1721 – H. Authorized by an edict of Louis XV *7 dated June 1721, these coins were only unoffi- *3 1791, United States. One cent. Bust portrait of cially circulated in Louisiana and other French 1788, New Jersey. -

Rare & Desirable Works on American Paper Money

Rare & Desirable Works on American Paper Money 141 W. Johnstown Road, Gahanna, Ohio 43230 • (614) 414-0855 • [email protected] Terms of Sale Items listed are available for immediate purchase at the prices indicated. No discounts are applicable. Items should be assumed to be one-of-a-kind and are subject to prior sale. Orders may be placed by post, email, phone or fax. Email or phone are recommended, as orders will be filled on a first-come, first-served basis. Items will be sent via USPS insured mail unless alternate arrangements are made. The cost for deliv- ery will be added to the invoice. There are no additional fees associated with purchases. Lots to be mailed to addresses outside the United States or its Territories will be sent only at the risk of the purchaser. When possible, postal insurance will be obtained. Packages covered by private insur- ance will be so covered at a cost of 1% of total value, to be paid by the buyer. Invoices are due upon receipt. Payment may be made via U.S. check, money order, wire transfer, credit card or PayPal. Bank information will be provided upon request. Unless exempt by law, the buyer will be required to pay 7.5% sales tax on the total purchase price of all lots delivered in Ohio. Purchasers may also be liable for compensating use taxes in other states, which are solely the responsibility of the purchaser. Foreign purchasers may be required to pay duties, fees or taxes in their respective countries, which are also the responsibility of the purchasers. -

FALL 2013 Garrett Metal Detectors®

FALL 2013 Garrett Metal Detectors® Kelley Rea of southeastern Virginia is topped that by finding four Virginia state serious about her relic hunting. And her seal coat buttons in the same location on finds prove that she has had her fair share another day. of success along the way. One of her secrets to success is to be She has only been detecting since diligent in working a productive area. She 2008, but the fact that Kelley lives in such often returns to a good site to work over a history-rich part of the country has cer- it again, slowly and carefully. More often tainly helped. “There is so much history than not, she succeeds in pulling more in this area, going back as far as the Revo- good items from even her most heavily lutionary War,” she says. “So, you never worked fields. know what you’re going to find.” There’s no real secret to why she stays She used several different brands of with the sport she has grown to love. “I metal detectors during her first few years just find it’s exciting,” says Kelley. in the field, but in the past two years she has settled into using a Garrett AT Pro. SEARCHER “It’s just an easy machine to learn and use,” according to Kelley. SPOTLIGHT With the AT Pro, she has unearthed an enviable collection of early silver coins, colonial coins, military buttons and bul- lets from the Civil War and Revolution- ary War, buckles, and various other early American artifacts. Some of her favorite rare coin finds have been a 1797 large cent, an 1865 two-cent coin, and a num- ber of cut pistareens (small Spanish sil- ver coins that first appeared in Colonial America in the early 1700s). -

Chapter One the History of Coins

15 CHAPTER ONE THE HISTORY OF COINS Regardless of their size, shape or value, regardless of the society, culture or era which spawned them, coins maintain an importance beyond their primary func- tion in commerce; they are the record and bearer of all of man’s history. They may be collected as historical objects, fine art, or struck to commemorate special events and occasions. As popular objects of intrinsic worth, coins have been hoarded in times of economic, political instability and particularly during wartime. Most significantly, quality rare coins have always increased in value: from virtually their inception to the present — with true historical monotonousness — coins have remained a good investment as well as the backbone of commerce. History, we have learned, repeats itself; and the history of coins does not disprove this maxim. To cover thousands of years of history very briefly: coins were first devised to fill the need for an unwavering scale of value. Prior to their existence, men were compelled to decide an exchange rate for each new trade. How much food for a pitcher of water? How many slaves for a wife? It was necessary, if cumbersome, for a trader to carry everything he might conceivably want to swap. Such was life under the barter economy. Life changed dramatically, however, with the appearance of money: a standard item of trade, against which every- thing of value might be measured. Initially, this did not mean coins. Shells, ani- mals, slaves, beads, salt, grain — all served as standards of exchange at different times and places. Certain commodities, among them cattle, and such useful implements as axes and knives, derived part of their value from the prestige asso- ciated with their ownership. -

Coins and Banknotes Lady a of the Property

Los Angeles | January 28, 2019 Coins and Banknotes Lady a of The Property Coins and Banknotes | Los Angeles | January 28, 2019 25528 Coins and Banknotes The Property of a Lady Los Angeles | Monday January 28, 2019 BONHAMS BIDS INQUIRIES REGISTRATION 7601 W. Sunset Boulevard +1 (323) 850 7500 Paul Song IMPORTANT NOTICE Los Angeles, California 90046 +1 (323) 850 6090 fax 323-436-5455 Please note that all customers, bonhams.com [email protected] irrespective of any previous activity To bid via the internet please visit with Bonhams, are required to PREVIEW www.bonhams.com/25528 Alexandra Schettini complete the Bidder Registration Friday January 25, 323-436-5508 Form in advance of the sale. The 12 noon to 5pm Please note that bids must be [email protected] form can be found at the back of Saturday January 26, submitted no later than 4pm on every catalogue and on our 12 noon to 5pm the day prior to the auction. New Jim Jones website at www.bonhams.com and Sunday January 27, bidders must also provide proof Special Consultant should be returned by email or 12 noon to 5pm of identity and address when post to the specialist department Monday, January 28, submitting bids. ILLUSTRATIONS or to the bids department at 9am to 12 noon Front cover: Lot 196 [email protected] Please contact client services with Session page: Lot 95 SALE NUMBER any bidding inquiries. Back cover: Lot 97 To bid live online and / or leave internet bids please go to 25528 Please see pages 76 to 78 for www.bonhams.com/ Lots 1 - 231 bidder information including auctions/24620 and click on Conditions of Sale, after-sale the Register to bid link at the CATALOG collection and shipment.