Healthy Performance Practice for Male Barbershop Singers

Total Page:16

File Type:pdf, Size:1020Kb

Load more

Recommended publications

-

Music Educator's Guide & Songbook

MUSIC EDUCATOR’S GUIDE & SONGBOOKIncludes: Barbershop Harmony Teaching Guide, Seven RoyaltyFree Songs, Barbershop Tags, and Accompanying Learning CD 2014 SPEBSQSA, Inc. 110 7th Ave. No., Nashville, TN 37203-3704, USA. Tel. (800) 876-7464 Permission granted to reproduce for personal and educational use only. Commercial copying, hiring, and lending is prohibited. www.barbershop.org #209532 Dear Music Educator: Thank you for your interest in Barbershop Harmony—one of the truly American musical art foorms! I think you will be surprised at the depth of instructional material and opportunities the Barbershop Harmony Society offers. More importantly, you’ll be pleased with the way your students accept this musical style. This guide contains a significant amount of information aboutt the barbershop style, as well as many helpful suggestions on how to teach it to your students. The songs included in this guide are an introduction to the barbershop style and include a part-predominant learning CD, all of which may be copied at no extra charge. For more barbershop music, our Harmony Marketplace offers thousands of barbershop arrangements, including PDF and mp3 demos, at www.barbershop.org/arrangementts. Songbooks, manuals, part-predominant learning CDs, educational videos and DVDs, merchandise, and more can be found at www.harmonymarketplace.com. For those who are not familiar with the Society or if you would like further information, please feel free to contact us at 1-800-876-SING or at [email protected]. Thanks again for your interest in the -

Islj{Ilat!Ajztk States

lj{ilAt!aJztK states isHew York City . POlice :Quartet .Bronx Chcrpter bYCity#] 1lk.,H'/IIf$'l'S . ./1idr.·Accollstii:alPeTseClltiliij Jaclson C!uIfl PUBLISHED BY MAY '6he SOCIETY FOR THE PRESERVATION AND ENCOURAGEMENT VOL. V. 1 946 OF BARBER SHOP QUARTET SINGING IN AMERICA, INC. No.4 Stu. HARMONIZER SIX OF OUR SEVEN CHAMPS STILL TOGETHER- We wonder at times whether or not ~ we are duly appreciative of the fact D£'.OlED TO T~T$ OF BA~BE~ OOA~TET HAP...oNY that of the seven quartets crowned SI.fOP "champions" since the Society was founded in 1938, six are still together Published quarterly by the International Officers and the other members of the International Board of Directors of the Society for the Preservation and and, in our opinion, singing better Encouragement of Barber Shop Quartet Singing in America, Inc., for free than ever. The War of course tem distribution to the members of the Society. porarily disrupted the ranks of the Bartlesville (Phillips 66) Barflies and VOLUME V MAY, 1946 No. 4 the Chord Busters, but now that the ,35c per Copy Marine Corps has sent Bob Holbrook home to Tulsa, and the Army Tom Carroll P. Adams - Editor and Business Manager Massengale to Tulsa and Bob Durand 18270 Grand River Avenue, Detroit 23, Michigan to Bartlesville, those two quartets are Phone: VE 7-7300 back together, and did they sing their I hearts out at the Oklahoma City Pa V CONTRIBUTING EDITORS rade on February 23rd! The only one O. C CASH GEORGE W, CAMPBELL JAMES F. KNIPE of our seven Champion quartets lost J. -

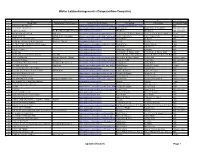

EXCEL LATZKO MUZIK CATALOG for PDF.Xlsx

Walter Latzko Arrangements (Computer/Non-Computer) A B C D E F 1 Song Title Barbershop Performer(s) Link or E-mail Address Composer Lyricist(s) Ensemble Type 2 20TH CENTURY RAG, THE https://www.sheetmusicplus.com/title/the-20th-century-rag-digital-sheet-music/21705300 Male 3 "A"-YOU'RE ADORABLE www.sheetmusicplus.com/title/a-you-re-adorable-digital-sheet-music/21690032Sid Lippman Buddy Kaye & Fred Wise Male or Female 4 A SPECIAL NIGHT The Ritz;Thoroughbred Chorus [email protected] Don Besig Don Besig Male or Female 5 ABA DABA HONEYMOON Chordettes www.sheetmusicplus.com/title/aba-daba-honeymoon-digital-sheet-music/21693052Arthur Fields & Walter Donovan Arthur Fields & Walter Donovan Female 6 ABIDE WITH ME Buffalo Bills; Chordettes www.sheetmusicplus.com/title/abide-with-me-digital-sheet-music/21674728Henry Francis Lyte Henry Francis Lyte Male or Female 7 ABOUT A QUARTER TO NINE Marquis https://www.sheetmusicplus.com/title/about-a-quarter-to-nine-digital-sheet-music/21812729?narrow_by=About+a+Quarter+to+NineHarry Warren Al Dubin Male 8 ACADEMY AWARDS MEDLEY (50 songs) Montclair Chorus [email protected] Various Various Male 9 AC-CENT-TCHU-ATE THE POSITIVE (5-parts) https://www.sheetmusicplus.com/title/ac-cent-tchu-ate-the-positive-digital-sheet-music/21712278Harold Arlen Johnny Mercer Male 10 ACE IN THE HOLE, THE [email protected] Cole Porter Cole Porter Male 11 ADESTES FIDELES [email protected] John Francis Wade unknown Male 12 AFTER ALL [email protected] Ervin Drake & Jimmy Shirl Ervin Drake & Jimmy Shirl Male 13 AFTER THE BALL/BOWERY MEDLEY Song Title [email protected] Charles K. -

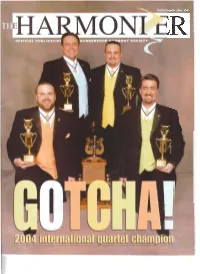

Sept-October 04-Ver F.Pmd

ONIbR September/ October 2004 VOLUME LXIV NUMBER 5 Features We’re having a super party Gallery: 14 before the Super Bowl! 32 Quartet contest New ways to have fun at the midwinter conven- tion will make Jacksonville one heckuva party 41 Chorus contest x-treme fun? GOTCHA! 16 Louisville had it all College contest The biggest week of the year was packed with su- 46 perb singing, brilliant costuming, and more ways to have fun barbershopping. Our inside scoop un- covers plenty you didn’t see. COMPLETE COVERAGE BY LORIN MAY Departments 2 50 LET’S HARMONIZE HARMONY FOUNDATION On the shoulders of giants Clarke Caldwell and Don Harris 4 lay it on the line THE PRESIDENT’S PAGE 54 Let’s enrich the lives of other people NOTEWORTHY On the Cover 6 Remembering writers, GOTCHA! TEMPO teachers, and singers and the A really wild wild card contest... 54 Ambassadors a new look... something funny’s STAY TUNED of Harmony happening in Salt Lake City What’s working get their golds 11 54 at last. LETTERS MEMBER SERVICE DIRECTORY Jim Clancy is the best Where to find answers, people, resources Photos by Jim Miller Photography Cover by Lorin May 12 60 HARMONY HOW-TO THE TAG Ten expectations of a champion Remembering Val Hicks and “That Summer When We Young” September/October 2004 • The HARMONIZER 1 LET’S HARMONIZE Don A. Harris, Chief Executive Officer On the shoulders of giants... As they say, sometimes what’s old is new. And oftentimes, the most meaningful words last longer than the paper they were written on. -

2018 FWD President Craig Hughes INSIDE: Conventions • Moh • Lou Laurel • Camp Fund 2 X Match • 2018 Officer Reports Ray S

Westunes Vol. 68 No. 1 Spring 2018 2018 FWD President Craig Hughes INSIDE: Conventions • MoH • Lou Laurel • Camp Fund 2 x Match • 2018 Officer Reports Ray S. Rhymer, Editor • Now in his 17th year EDITORIAL STAFF Editor in Chief Northeast Division Editor Ray S. Rhymer [email protected] Roger Perkins [email protected] Marketing & Advertising Northwest Division Editor David Melville [email protected] Don Shively [email protected] Westags Newsletter Southeast Division Editor Jerry McElfresh [email protected] Greg Price [email protected] Arizona Division Editor Southwest Division Editor Bob Shaffer [email protected] Justin McQueen [email protected] Westunes Vol. 68 No. 1 Features Spring 2018 2018 Spring Convention Remembering Lou Laurel International Quartet Preliminary Contest, Southeast A Past International President and Director of & Southwest Division Quartet and Chorus Contests, two different International Champion chapters is 3 and the FWD High School Quartet Contest. 8 remembered by Don Richardson. 2018 Arizona Division Convention 2018 Harmony Camp Celebrating the 75th year of Barbershop in Mesa, AZ Hamony Camp will be held again in Sly Park, CA with with Harmony Platoon, AZ Division Quartet and Chorus Artistic License and Capitol Ring assisting. Tell the 4 & Harmony Inc. Chorus Contests & AFTERGLOW. 9 young men in your area about it. 2018 NE & NW Division Convention Lloyd Steinkamp Endowment Fund Northeast and Northwest Division Quartet and Cho- A major donor stepped up to “double” match 5 rus Contests in Brentwood, CA, a new location. 10 contributions in 2018. 2017 Int’l Champion Masters of Harmony Marketing Wisely on a Shoe-String Budget A Masters of Harmony update after winning their first David Melville brings a different view of marketing - gold medal in San Francisco in 1990 and their ninth in you may rethink your procedures after reading this 6 Las Vegas in 2017 .. -

Four Rascals Story

GradyGrady Kerr’sKerr’s PreservationPreservation ProjectProject The Lost Quartet Series MastersMasters ofof MischiefMischief See Page 9 The Preservation Project Lost Quartet Series October 2016 TheThe PreservationPreservation ProjectProject is published as a continuation and adaptation of the award winning magazine, PRESERVATION, created by Barbershop Historian Grady Kerr. It is our goal to promote, educate, and pay tribute to those who came before and made it possible for us to enjoy the close harmony performed by thousands of men and women today. Your Preservation Crew Society Historian / Researcher / Writer / Editor / Layout Our sincere thanks to the following people Grady Kerr who helped gather information in this issue: [email protected] Don Dobson Patient Proofreaders & Fantastic Fact Checkers Jimmy & Lois Vienneau Ann McAlexander Haley Vienneau Bob Sutton Fran & Sheila Page Nancy Hertz Ellis Bobby & Kathy Pierce Lisa Spirito Graphic Supervisor Production Supervisor Steve Spirito Bruce Checca Leo Larivee Terry Clarke Rich Knapp All articles herein, unless otherwise credited, are written by the editor and do not necessarily reflect the opinions Jim Bader of the Barbershop Harmony Society, any District, any historian, any barbershopper, the BHS HQ Staff , Richard Millard Jr. or the EDITOR. Ken Thomas Daniel Costello Carl Hancuff Did you see Bob Franklin our last issue Harlan Wilson on the Norm Mendenhall Jax of Joe Schlesinger Harmony? Bob Sutton Leo Larivee READ IT Elizabeth Davies HERE James Given Curtis Terry Eddie Holt Lorin May PRESERVATION Tom Emmert John Scott Crawford Online! Robert Kelly All past 23 issues of PRESERVATION Robert Disney are available for FREE Guy Haas Ryan Iorio 2 The Preservation Project Lost Quartet Series October 2016 The TRUETRUE Story Behind the FoundingTRUETRUE of S.P.E.B.S.Q.S.A. -

~Keep the Wiiole World Singing

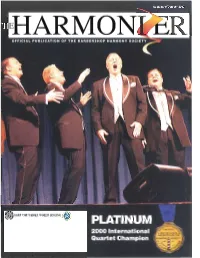

~ KEEP THE WIIOLE WORLD SINGING (i) The 2000 Intemational Chorus and Quartet Contests..... Videos, Cassettes and Compact Discs. Order now and save!! tttM'~ 'tv1 tM'ketp1..c«:.e- Stock # Item Description Qty Each Total SPEBSQSA, Inc. 4652 2000 Quartet Cassette $11.95 6315 Harmony Lane 4653 2000 Chorus Cassette $11.95 Kenosha. WI 53143-5199 order both· save $4.00 (800) 876-7464 Pax: (262) 654-5552 4654 2000 Quartet CD $14.95 Delivery in time for Christmas giving in 4655 2000 Chorus CD $14.95 2000. order both - save $5.00 4165 2000 VHS Quartet Video $24.95 Please ship my order to: 4166 2000 VHS Chorus Video $24.95 Name, _ order both· save $5.00 4118 2000 *PAL Quartet Video $30.00 Sireel _ 4119 2000 *PAL Chorus Video $30.00 City _ order both· save $10.00 Total for merchandise SlalelProv ZIP _ 5% Sales Tax (Wis. residents only) Subtotal SPEBSQSA membership no. _ Shipping and handling (see below) Chapler name & no. _ Total Amount enclosed US FUNDS ONLY Use yOll MBNA America credit card! *pAL (European Formal) !,YISA.,! ..... PackClges set" to separate (ufdresses require separate pOS/(lge. Please mId: Credit card cuslomers only: US Dnd Canadian shipments Foreign shipments (your card wifl be charged /Jrior to the anticipated 56.00 shipping and handling charge $15.00 overseas shipping and handling charge de/il'el)' date) Please charge my _ Mastercard _Visa Account No. Expires _ Soptomborl Oclobor 2000 T VOLUME EHARMONl~R LX NUMBER • : f • •• ••• • 5 THE SMOOTH TRANSFER OF POWER. Exhausted from their year as champs, FRED graciously passes the title to PLATINUM. -

Chapter 2 Music in the United States Before the Great Depression

American Music in the 20th Century 6 Chapter 2 Music in the United States Before the Great Depression Background: The United States in 1900-1929 In 1920 in the US - Average annual income = $1,100 - Average purchase price of a house = $4,000 - A year's tuition at Harvard University = $200 - Average price of a car = $600 - A gallon of gas = 20 cents - A loaf of Bread = 20 cents Between 1900 and the October 1929 stock market crash that triggered the Great Depression, the United States population grew By 47 million citizens (from 76 million to 123 million). Guided by the vision of presidents Theodore Roosevelt1 and William Taft,2 the US 1) began exerting greater political influence in North America and the Caribbean.3 2) completed the Panama Canal4—making it much faster and cheaper to ship its goods around the world. 3) entered its "Progressive Era" by a) passing anti-trust laws to Break up corporate monopolies, b) abolishing child labor in favor of federally-funded puBlic education, and c) initiating the first federal oversight of food and drug quality. 4) grew to 48 states coast-to-coast (1912). 5) ratified the 16th Amendment—estaBlishing a federal income tax (1913). In addition, by 1901, the Lucas brothers had developed a reliaBle process to extract crude oil from underground, which soon massively increased the worldwide supply of oil while significantly lowering its price. This turned the US into the leader of the new energy technology for the next 60 years, and opened the possibility for numerous new oil-reliant inventions. -

MUSIC NOTES: Exploring Music Listening Data As a Visual Representation of Self

MUSIC NOTES: Exploring Music Listening Data as a Visual Representation of Self Chad Philip Hall A thesis submitted in partial fulfillment of the requirements for the degree of: Master of Design University of Washington 2016 Committee: Kristine Matthews Karen Cheng Linda Norlen Program Authorized to Offer Degree: Art ©Copyright 2016 Chad Philip Hall University of Washington Abstract MUSIC NOTES: Exploring Music Listening Data as a Visual Representation of Self Chad Philip Hall Co-Chairs of the Supervisory Committee: Kristine Matthews, Associate Professor + Chair Division of Design, Visual Communication Design School of Art + Art History + Design Karen Cheng, Professor Division of Design, Visual Communication Design School of Art + Art History + Design Shelves of vinyl records and cassette tapes spark thoughts and mem ories at a quick glance. In the shift to digital formats, we lost physical artifacts but gained data as a rich, but often hidden artifact of our music listening. This project tracked and visualized the music listening habits of eight people over 30 days to explore how this data can serve as a visual representation of self and present new opportunities for reflection. 1 exploring music listening data as MUSIC NOTES a visual representation of self CHAD PHILIP HALL 2 A THESIS SUBMITTED IN PARTIAL FULFILLMENT OF THE REQUIREMENTS FOR THE DEGREE OF: master of design university of washington 2016 COMMITTEE: kristine matthews karen cheng linda norlen PROGRAM AUTHORIZED TO OFFER DEGREE: school of art + art history + design, division -

Let Freedom Ring!

Summer 2010 Let Freedom Ring! Barbershopping in Philly by Craig Rigg [The following report is a personal observation and does not reflect the views of the Society or the Illinois District. With luck we’ll face only a few lawsuits.] There’s this moment in the recent barbershop documentary Amer- ican Harmony. Jeff Oxley looks at a monitor as Vocal Spectrum appears on stage during the 2006 quartet contest, singing “Cruella DeVille.” He turns and shakes his head, saying, “The So- ciety’s changing, man.” His sentiments pretty much sum up what the 2010 International Convention and Con- tests at Philadelphia was all about. There’s been a changing of the guard. First, let's take the quartet contest. By now, everybody knows that Storm Front finally got the gold (after much cajoling and trash talk). They are the first comedy oriented quartet since FRED to achieve the pinnacle of quartetting. There’s no doubt these guys can sing; they’re Singing scores put them in second place, bested only by Old School (with Illinois's own Joe Krones at bass). In fact, Old School led after the semi-finals by only 17 points, and OS had won each of the first two rounds. All they had to do was maintain their lead and the gold was theirs. Not to be (a phrase you'll hear again later.) So what did Storm Front do that made the difference? Well, a combination of factors proba- bly did it. First, SF staged one heck of an innovative final set. Their first song, with a bit of mock- ing of Old School and up-and-coming Ringmasters from Sweden, lamented their struggle to reach the top. -

Historical Highlights

Historical Highlights 1943 We start with Racine (Chapter # 1) 1945 Wisconsin Association of Chapters formed at Milwaukee following meeting at Appelton. First District Quartet contest held at Milwaukee. 1946 First District Chorus contest of entire Society held at Oshkosh, WI 1947 Name of District changed to Land O’Lakes District Assn of Chapters and later enlarged to include MN and Upper Peninsula of MI. Int’l Convention held at Milwaukee. Milwaukee Chorus introduces Willis Diekema’s “Keep America Singing”. 1948 O.H.King Cole of Manitowoc and Sheboygan chapters elected International President. International Home Building Fund started with contribution by Sheboygan chapter. Manitoba added to LO’L Assn. 1949 Achievement Awards to chapters inaugurated. O.H.King Cole reelected Int’l President. First District Directory published. 1950 Harmony News, first district monthly publication of entire Society published with Hans Beyer as editor. North Dakota, Saskatchewan and counties of Kenora, Thunder Bay and Rainy River in Ontario added to L O’L. 1951 Schmitt Brothers crowned International Champs at Toledo. LO’L District Incorporated. 1952 Four Teens, members of Eau Claire chapter, while in military service crowned International Champs at Kansas City. 1953 John Z Means of Manitowoc chapter elected International President. 1954 Int’l Mid-Winter convention held in Minneapolis. LO’L largest district with 2669. 1955 Janesville, WI chorus crowned International Champs. LOL BOTY award inaugurated. 1956 International Convention held in Minneapolis. 1957 International Headquarters moves to Kenosha, WI. 1958 District reorganized into 5 regions, each supervised by a Vice President. 1959 Hans Beyer retires as Editor of Harmony News after 10 years. -

Preservation January 2013

The Official Publication of the Barbershop Harmony Society’s Historical Archives Volume 4, No. 1 Living In The Past - And Proud Of It! January 2013 Here’sHere’s ToTo TheThe LosersLosers 139th Street Quartet / Bank Street / Center Stage / Four Rascals / Metropolis / Nighthawks / Pacificaires / Playtonics / Riptide / Roaring 20s / Saturday Evening Post / Sundowners / Vagabonds In This Issue Pages Here’s To The Losers 13-50 Don Beinema 1921-2013 50 Victoria Leigh Soto 3 New York Treasure Hunt 5-6 75 Year Logo Has A Secret 4 SeeSee PagePage 1313 Flat Foot Four Footage Found 6 All articles herein - unless otherwise credited - were written by the editor 2 Volume 4, No. 1 January 2013 Published by the Society Archives Committee of the Barbershop Harmony Society for all those interested in preserving, promoting and educating others as to the rich history of the Barbershop music genre and the organization of men that love it. Society Archives Committee Grady Kerr - Texas (Chairman) Bob Sutton - Virginia Steve D'Ambrosio - Tennessee Bob Davenport - Tennessee Bob Coant - New York Ann McAlexander - Indianapolis, IN Touché Win Crowns Patty Leveille - Tennessee (BHS Staff Liaison) Congratulations to the new 2013 Society Historian / Editor / Layout International Queens of Harmony, Touché - Grady Kerr Patty Cobb Baker, Gina Baker, Jan Anton [email protected] and Kim McCormic. th In November, about 6,000 attended the 66 Proofreaders & Fact Checkers Bob Sutton, Ann McAlexander & Matthew Beals annual Sweet Adeline International With welcomed assists by Leo Larivee Convention in Denver, Colorado. More than 65 quartets and 40 choruses competed in five contests over the course of the week.