Practices That Work.Pdf

Total Page:16

File Type:pdf, Size:1020Kb

Load more

Recommended publications

-

Marine-Oriented Sama-Bajao People and Their Search for Human Rights

Marine-Oriented Sama-Bajao People and Their Search for Human Rights AURORA ROXAS-LIM* Abstract This research focuses on the ongoing socioeconomic transformation of the sea-oriented Sama-Bajao whose sad plight caught the attention of the government authorities due to the outbreak of violent hostilities between the armed Bangsa Moro rebels and the Armed Forces of the Philippines in the 1970s. Among hundreds of refugees who were resettled on land, the Sama- Bajao, who avoid conflicts and do not engage in battles, were displaced and driven further out to sea. Many sought refuge in neighboring islands mainly to Sabah, Borneo, where they have relatives, trading partners, and allies. Massive displacements of the civilian populations in Mindanao, Sulu, and Tawi- Tawi that spilled over to outlying Malaysia and Indonesia forced the central government to take action. This research is an offshoot of my findings as a volunteer field researcher of the Commission on Human Rights (CHR) and the National Commission on Indigenous People (NCIP) to monitor the implementation of the Indigenous People’s Rights to their Ancestral Domain (IPRA Law RA 8371 of 1997). Keywords: inter-ethnic relations, Sama-Bajao, Taosug, nomadism, demarcation of national boundaries, identity and citizenship, human rights of indigenous peoples * Email: [email protected] V olum e 18 (2017) Roxas-Lim Introduction 1 The Sama-Bajao people are among the sea-oriented populations in the Philippines and Southeast Asia. Sama-Bajao are mentioned together and are often indistinguishable from each other since they speak the same Samal language, live in close proximity with each other, and intermarry. -

THE SUBDIALECT FILIPINO Guerrero De La Paz

THE SUBDIALECT FILIPINO Guerrero de la Paz What is "Filipino?" There is much difference of opinion on this matter. According to one school of thought, Filipino is not only different from Tagalog, but that it (Filipino) still does not exist, but on the contrary, it still has to be developed. If one were to pursue this argument to its logical conclusion, it would lead to the authorities stopping the compulsory teaching of "Filipino" in schools, and ending its use in government, since such a language still does not exist. That this opinion has influence even in government can be gleaned from the fact that it was the argument used by the Cebu Regional Trial Court in 1990, when it stopped the Department of Education, Culture and Sports and its officials in the Central Visayas from requiring the use of Filipino as a medium of instruction in schools in Cebu (Philippine Daily Inquirer, June 10, 1990). We all know that this issue became moot and academic when the Cebu Provincial Board withdrew the ban on the compulsory teaching of the putative national language on the "request" of then President Joseph Estrada in 1998. http://newsflash.org/199810/ht/ht000561.htm On the other hand, the predominant view these days (incidentally, that held by the authorities, at least at DepEd/DepTag) is that Filipino already exists. The following is taken from an article by the late Bro. Andrew Gonzalez, one of the staunch supporters of Filipino: "The national language of the Philippines is Filipino, a language in the process of development and modernisation; it is based on the Manila lingua franca which is fast spreading across the Philippines and is used in urban centers into the country. -

Chapter 4 Safety in the Philippines

Table of Contents Chapter 1 Philippine Regions ...................................................................................................................................... Chapter 2 Philippine Visa............................................................................................................................................. Chapter 3 Philippine Culture........................................................................................................................................ Chapter 4 Safety in the Philippines.............................................................................................................................. Chapter 5 Health & Wellness in the Philippines........................................................................................................... Chapter 6 Philippines Transportation........................................................................................................................... Chapter 7 Philippines Dating – Marriage..................................................................................................................... Chapter 8 Making a Living (Working & Investing) .................................................................................................... Chapter 9 Philippine Real Estate.................................................................................................................................. Chapter 10 Retiring in the Philippines........................................................................................................................... -

List of Ecpay Cash-In Or Loading Outlets and Branches

LIST OF ECPAY CASH-IN OR LOADING OUTLETS AND BRANCHES # Account Name Branch Name Branch Address 1 ECPAY-IBM PLAZA ECPAY- IBM PLAZA 11TH FLOOR IBM PLAZA EASTWOOD QC 2 TRAVELTIME TRAVEL & TOURS TRAVELTIME #812 EMERALD TOWER JP RIZAL COR. P.TUAZON PROJECT 4 QC 3 ABONIFACIO BUSINESS CENTER A Bonifacio Stopover LOT 1-BLK 61 A. BONIFACIO AVENUE AFP OFFICERS VILLAGE PHASE4, FORT BONIFACIO TAGUIG 4 TIWALA SA PADALA TSP_HEAD OFFICE 170 SALCEDO ST. LEGASPI VILLAGE MAKATI 5 TIWALA SA PADALA TSP_BF HOMES 43 PRESIDENTS AVE. BF HOMES, PARANAQUE CITY 6 TIWALA SA PADALA TSP_BETTER LIVING 82 BETTERLIVING SUBD.PARANAQUE CITY 7 TIWALA SA PADALA TSP_COUNTRYSIDE 19 COUNTRYSIDE AVE., STA. LUCIA PASIG CITY 8 TIWALA SA PADALA TSP_GUADALUPE NUEVO TANHOCK BUILDING COR. EDSA GUADALUPE MAKATI CITY 9 TIWALA SA PADALA TSP_HERRAN 111 P. GIL STREET, PACO MANILA 10 TIWALA SA PADALA TSP_JUNCTION STAR VALLEY PLAZA MALL JUNCTION, CAINTA RIZAL 11 TIWALA SA PADALA TSP_RETIRO 27 N.S. AMORANTO ST. RETIRO QUEZON CITY 12 TIWALA SA PADALA TSP_SUMULONG 24 SUMULONG HI-WAY, STO. NINO MARIKINA CITY 13 TIWALA SA PADALA TSP 10TH 245- B 1TH AVE. BRGY.6 ZONE 6, CALOOCAN CITY 14 TIWALA SA PADALA TSP B. BARRIO 35 MALOLOS AVE, B. BARRIO CALOOCAN CITY 15 TIWALA SA PADALA TSP BUSTILLOS TIWALA SA PADALA L2522- 28 ROAD 216, EARNSHAW BUSTILLOS MANILA 16 TIWALA SA PADALA TSP CALOOCAN 43 A. MABINI ST. CALOOCAN CITY 17 TIWALA SA PADALA TSP CONCEPCION 19 BAYAN-BAYANAN AVE. CONCEPCION, MARIKINA CITY 18 TIWALA SA PADALA TSP JP RIZAL 529 OLYMPIA ST. JP RIZAL QUEZON CITY 19 TIWALA SA PADALA TSP LALOMA 67 CALAVITE ST. -

G.R. No. 77372 April 29, 1988 LUPO L. LUPANGCO, RAYMOND S

G.R. No. 77372 April 29, 1988 Branch XXXII, a complaint for injuction with a prayer with LUPO L. LUPANGCO, RAYMOND S. MANGKAL, NORMAN the issuance of a writ of a preliminary injunction against A. MESINA, ALEXANDER R. REGUYAL, JOCELYN P. respondent PRC to restrain the latter from enforcing the CATAPANG, ENRICO V. REGALADO, JEROME O. ARCEGA, above-mentioned resolution and to declare the same ERNESTOC. BLAS, JR., ELPEDIO M. ALMAZAN, KARL unconstitution. CAESAR R. RIMANDO, petitioner, Respondent PRC filed a motion to dismiss on October 21, vs. 1987 on the ground that the lower court had no jurisdiction COURT OF APPEALS and PROFESSIONAL REGULATION to review and to enjoin the enforcement of its resolution. In COMMISSION, respondent. an Order of October 21, 1987, the lower court declared that Balgos & Perez Law Offices for petitioners. it had jurisdiction to try the case and enjoined the respondent commission from enforcing and giving effect to The Solicitor General for respondents. Resolution No. 105 which it found to be unconstitutional. Not satisfied therewith, respondent PRC, on November 10, GANCAYCO, J.: 1986, filed with the Court of Appeals a petition for the Is the Regional Trial Court of the same category as the nullification of the above Order of the lower court. Said Professional Regulation Commission so that it cannot pass petiton was granted in the Decision of the Court of Appeals upon the validity of the administrative acts of the latter? promulagated on January 13, 1987, to wit: Can this Commission lawfully prohibit the examiness from WHEREFORE, finding the petition meritorious the same is attending review classes, receiving handout materials, tips, hereby GRANTED and the other dated October 21, 1986 or the like three (3) days before the date of the issued by respondent court is declared null and void. -

2007 BDO Annual Report Description : Building for the Future

B U I L D I N G 07 annual FOR THE FUTURE report FINANCIAL HIGHLIGHTS CORPORATE MISSION To be the preferred bank in every market we serve by consistently providing innovative products and flawless delivery of services, proactively reinventing (Bn PhP) 2006 2007 % CHANGE RESOURCES 628.88 617.42 -1.8% ourselves to meet market demands, creating shareholder value through GROSS CUSTOMER LOANS 257.96 297.03 15.1% superior returns, cultivating in our people a sense of pride and ownership, DEPOSIT LIABILITIES 470.08 445.40 -5.3% and striving to be always better than what we are today…tomorrow. CAPITAL FUNDS 52.42 60.54 15.5% NET INCOME 6.39 6.52 2.0% CORE VALUES RESOURCES CAPITAL FUNDS Commitment to Customers 700 70 We are committed to deliver products and services that surpass customer 600 60 629 617 61 expectations in value and every aspect of customer service, while remaining to 500 50 52 ) 400 ) 40 be prudent and trustworthy stewards of their wealth. P P h h P P 300 30 (Bn (Bn Commitment to a Dynamic and Efficient Organization 200 20 234 20 180 17 We are committed to creating an organization that is flexible, responds to 100 149 10 15 0 0 change and encourages innovation and creativity. We are committed to the 03 04 05 06 07 03 04 05 06 07 process of continuous improvements in everything we do. BDO Merged BDO-EPCI BDO Merged BDO-EPCI Commitment to Employees GROSS CUSTOMER LOANS DEPOSIT LIABILITIES NET INCOME We are committed to our employees’ growth and development and we 350 500 7.0 will nurture them in an environment where excellence, integrity, teamwork, 300 470 6.0 6.5 445 6.4 297 400 250 5.0 professionalism and performance are valued above all else. -

People of the Philippines Vs. Sylvia P. Binarao

REPUBLIC OF THE PHILIPPINES SANDIGANBAYAN QUEZON CITY SPECIAL THIRD DIVISION PEOPLE OF THE PHILIPPINES, Plaintiff, SB-12-CRM-OO 16 For: Estafa through Falsification of Public Documents -versus- SB-12-CRM-0017-0018 For: Malversation of Public Funds SB-12-CRM-00 19-0020 For: Falsification SB-12-CRM-0021-0023 SYLVIA P. BINARAO, For: Violation of Sec. 3(e), R.A. No. 3019 x---------- Accused. ----------------------------x Present: CABOTAJE-TANG, P.J. FERNANDEZ, SJ. 1, J. TRESPESES, Z.2 J., Promulgated: ~\.7G1M ~L/(2b]U X----------------------------------------------------------------------~ DECISION CABOTAJE-TANG, P.J.: 1This case was submitted for decision when J. Fernandez, now Chairperson of the Sixth Division, was still a senior member of the Third Division. ~ 2 Sitting as a special member per Administrative Order No. 227-2016 dated July 26, 2016 / 4;' 2 DECISION People vs. Binarao SB-12-CRM-0016 to 0023 x------------------------------------------------ x THE CASE · Accused Sylvia P. Binarao stands charged of the crimes of: (1) estafa through falsification of public documents under Articles 318 and 171 [6],in relation to Article 48, of the Revised Penal Code [RPC],(2) malversation of public funds under Article 217 of the RPC on two [2] counts, (3) falsification of public documents under Article 171 [6] of the RPC on two [2] counts, and (4) violation of Section 3 [e]of Republic Act [R.A.]No. 3019, on three [3] counts. The Informations charging the accused of the said crimes respectively read: SB-12-CRM-OO 16 Estafa Through Falsification -

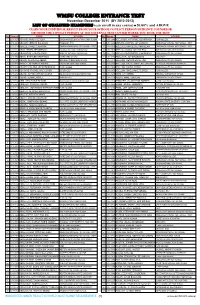

Wmsu College Entrance Test

WMSU COLLEGE ENTRANCE TEST November-December 2011 (SY 2012-2013) LIST OF QUALIFIED EXAMINEES (can enroll in any course) - 50.00% and ABOVE CLAIM YOUR INDIVIDUAL RESULT FROM YOUR SCHOOL CONTACT PERSON/GUIDANCE COUNSELOR OR FROM THE CONTACT PERSON AT THE EXTERNAL TEST CENTER WHERE YOU TOOK THE TEST No. Appno NAME SCHOOL No. Appno NAME SCHOOL 1. 1213-07275 ABAJAR, MARLY GEROSA ZAMBOANGA SIBUGAY NATIONAL HIGH SCHOOL 75. 1213-02888 ABELADOR, KATHRINE AZCARRAGA PILAR COLLEGE 2. 1213-09242 ABAJAR, MERLYN BULAWAN TUNGAWAN - ESU 76. 1213-10289 ABELITA, LUCHAN JOY LABADIA ZAMBOANGA NATIONAL HIGH SCHOOL - WEST 3. 1213-01027 ABALLE, XYRUS CABARON ZAMBOANGA NATIONAL HIGH SCHOOL - WEST 77. 1213-01614 ABELLA, EVANGELINE SANTILLAN ZAMBOANGA NATIONAL HIGH SCHOOL - WEST 4. 1213-07273 ABAN, SHARA MEI AMPONG PALOMOC NATIONAL HIGH SCHOOL 78. 1213-08622 ABELLA, GLAISA JOY GUCELA MABUHAY NATIONAL HIGH SCHOOL 5. 1213-08529 ABANGGAN, LAILA LLANOS MABUHAY NATIONAL HIGH SCHOOL 79. 1213-03163 ABELLA, MA RODESSA VILLANUEVA ZAMBOANGA CITY HIGH SCHOOL 6. 1213-09762 ABANI, BRETNEE MAMANGLU NOTRE DAME OF SIASI 80. 1213-07372 ABELLANA, JOY BALLESCAS IMELDA-ESU 7. 1213-00273 ABAÑO, SHAYENAZ ABBAS REGIONAL SCIENCE HIGH SCHOOL 81. 1213-10418 ABELLON, DENNIS ESCULTOR ZAMBOANGA CITY HIGH SCHOOL 8. 1213-04722 ABANTE, REYNANTE BALNIG LAMITAN NATIONAL HIGH SCHOOL 82. 1213-09567 ABELLON, NEZAL MARIE ALEJANDRO ATENEO DE ZAMBOANGA UNIVERSITY 9. 1213-02327 ABASTILLAS, IRIS JOY PADERANGA PILAR COLLEGE 83. 1213-03432 ABELLON, NIKAELA EBOL ZAMBOANGA CITY HIGH SCHOOL 10. 1213-08930 ABATAYO, RACHEL MAE CUYOS AURORA-ESU 84. 1213-02873 ABELLON, SHIELA MAE FLORES PILAR COLLEGE 11. 1213-02864 ABATO, ALYSSA JEHAN KULONG TALON-TALON NATIONAL HIGH SCHOOL 85. -

Report on Regional Economic Developments

Report on Regional Economic Developments Second Semester 2007 Department of Economic Research Monetary Stability Sector Bangko Sentral ng Pilipinas Regional Economic Development in the Philippines Second Semester 2007 Foreword In June 2005, the Monetary Board approved the release of the maiden issue of the BSP’s Report on Regional Economic Developments in the Philippines. The report widens the scope of BSP’s market surveillance, adding a geographic dimension to the economic indicators that it monitors regularly. Analysis of regional trends and developments are valuable inputs in monetary policy formulation and financial supervision. The report tracks economic developments in the regions, focusing on the demand and supply conditions, price developments and monetary conditions, as well as emerging economic outlook. It helps confirm the results of the business and consumer expectations surveys conducted by the BSP. Moreover, identifying opportunities and challenges faced by the different regions enhances further the BSP’s forward-looking and proactive approach to monetary policy. Regional performance is gauged using developments in output, prices, and employment. Selected key indicators in each of the major sectors of the economy are the focus of the surveillance. Agriculture covers rice and corn, crops such as banana, livestock, fishery, and poultry production. In industry, the number of building permits and housing starts are used to measure construction activity; while in the services sector, hotel occupancy rate and banking sector performance are analyzed. Developments in major industries particular to each region are also included. Qualitative and quantitative information used in the report are collected from primary and secondary sources and reflect the extensive information gathered by the BSP regional offices and branches on a provincial level. -

Zamboanga City - Wikipedia, the Free Encyclopedia Log in / Create Account Article Discussion Edit This Page History

Zamboanga City - Wikipedia, the free encyclopedia Log in / create account article discussion edit this page history Zamboanga City From Wikipedia, the free encyclopedia Coordinates: 6°54′N 122°4′E City of Zamboanga Officially, the City of Zamboanga (Chavacano de Zamboanga/Spanish: Ciudad de Zamboanga) is a highly-urbanized city located on the island of Mindanao in the Philippines. It is one of the navigation El Ciudad de Zamboanga first chartered cities and the sixth largest in the country. Zamboanga City is also one of several cities in the Philippines that are independent of any province. The word Zamboanga is an evolution Ciudad de Zamboanga Main page of the original Subanon word - Bahasa Sug jambangan, which means garden. Contents Featured content Philippine Commonwealth Act No. 39 of 1936 signed by President Manuel L. Quezon on October 12, 1936 in Malacañang Palace created and established Zamboanga as a chartered city. It has Current events been known variously as "El Orgullo de Mindanao" (The Pride of Mindanao), nicknamed the "City of Flowers," and affectionately called by Zamboangueños as "Zamboanga Hermosa" - Random article Chavacano/Spanish for "Beautiful Zamboanga." Today, the city is commercially branded for tourism by the city government as "Asia's Latin City," a clear reference to Zamboanga's identification with the Hispanized cultures of "Latin America" or the USA's "Latino" subculture. the City was formerly a part of the Commonwealth Era Moro Province of Mindanao. Its ancient inhabitants were Flag search vassals of the Sultanate of Sulu and North Borneo. Seal Zamboanga City is one of the oldest cities in the country and is the most Hispanized. -

TOYM IMAO, Sculptor + Painter [email protected] Tel

TOYM IMAO, Sculptor + Painter [email protected] www.toymimao.com Tel. 02-941-3245; 0920-9017915 EDUCATION 2012 M.F.A. Sculpture: Rinehart School of Sculpture at Maryland Institute College of Art, Baltimore, MD 2010 M.F.A. (Candidate): College of Fine Arts, University of the Philippines, Diliman, Quezon City, Philippines 2010 Directing Motion Pictures: Marilou Diaz-Abaya Film Institute, Antipolo City, Philippines 2003 Managing the Arts Program: Asian Institute of Management, Makati City, Philippines 1992 B.S. Architecture: College of Architecture, University of the Philippines, Diliman, Quezon City, Philippines SCHOLARSHIPS AND GRANTS 2015 Philippine Delegate, ASEAN Cultural Heritage and Identities Conference, Bangkok, Thailand 2012 – 2014 Artist-in Residence, The Creative Alliance, Baltimore, Maryland 2012 Apperson Fellowship, The Creative Alliance, Baltimore, Maryland 2012 Amalie Rothschild 34’ Award, Maryland Institute College of Art 2012 MICA Alumni Leadership Award, Maryland Institute College of Art 2012 Rinehart Award, Maryland Institute College of Art, Baltimore, MD. 2010 – 2012 Fulbright Scholarship 2010 – 2012 William M. Philips ’54 Memorial Scholarship, Maryland Institute College of Art, Baltimore, MD. 2010 – 2012 Rinehart School of Sculpture Scholarship, Maryland Institute College of Art, Baltimore, MD. 2002 Participant, 2nd International Sculpture Symposium, Hue, Vietnam, through grants from the Ford Foundation and Rockefeller Foundation SELECTED AWARDS 2016 Best Set Design for Tanghalang Pilipino’s Mabining Mandirigma, 8th -

Manila LIST of LICENSED GOVERNMENT and PRIVATE HOSPITALS As of December 31, 2020

Republic of the Philippines Department of Health HEALTH FACILITIES AND SERVICES REGULATORY BUREAU Manila LIST OF LICENSED GOVERNMENT AND PRIVATE HOSPITALS as of December 31, 2020 SERVCE MEDICAL DIRECTOR/ CAPABILIT E-MAIL REGION PROVINCE CITY LOCATION OWNERSHIP NAME OF HOSPITAL ABC CHIEF OF HOSPITAL CLASS Y CONTACT NOS. ADDRESS FAX NO. MOBILE NO. Barangay Abaca, Bangui, banguidh@g 1 ILOCOS REGION ILOCOS NORTE Ilocos Norte GOVT Province BANGUI DISTRICT HOSPITAL 25 Dr. Walberg Samonte General Level 1 077-676-1158 mail.com Barangay 6, San Julian, MARIANO MARCOS MEMORIAL Dr. Maria Lourdes K. 077- mmmh_doh@ 2 ILOCOS REGION ILOCOS NORTE Batac, Ilocos Norte GOVT DOH-RET HOSPITAL AND MEDICAL CENTER 200 Otayza General Level 3 7923144/6008000 yahoo.com 7923133 Airport Road, Barangay 46 Nalbo, Laoag City, Dr. Francis Manolito B. lcgh_lc@yaho 3 ILOCOS REGION ILOCOS NORTE Laoag City Ilocos Norte GOVT City LAOAG CITY GENERAL HOSPITAL 50 Dacuycuy General Level 1 077-670-6304 o.com Brgy. 23 San Matias, P. Gomez St., Laoag City, GOV. ROQUE B. ABLAN SR. 077- pho_grbasmh 4 ILOCOS REGION ILOCOS NORTE Laoag City Ilocos Norte GOVT LGU MEMORIAL HOSPITAL 100 Dr. Roger G. Braceros General Level 2 7731770/7720303 @yahoo.com 7704155 bessangpass memorialhosp National Road, ILOCOS SUR DISTRICT HOSPITAL - [email protected] 5 ILOCOS REGION ILOCOS SUR Cervantes, Ilocos Sur GOVT Province BESSANG PASS CERVANTES 25 Dr.Theresa Basabas -OIC General Level 1 0939-844-4341 m cisdhhospital Paratong, Narvacan, ILOCOS SUR DISTRICT HOSPITAL - Dr. Ronald Remegio T. @yahoo.com 6 ILOCOS REGION ILOCOS SUR Ilocos Sur GOVT Province NARVACAN 50 Tobias General Level 1 077-604-0271 tagudin_hospi ILOCOS SUR DISTRICT HOSPITAL - [email protected] 077-748- 7 ILOCOS REGION ILOCOS SUR Bio, Tagudin, Ilocos Sur GOVT Province TAGUDIN 50 Dr.