Agon Lost – Or in Disguise? a Commentary

Total Page:16

File Type:pdf, Size:1020Kb

Load more

Recommended publications

-

Going up a Mountain

Going Up a Mountain Going Up a Mountain by ReadWorks Mount Everest is the tallest mountain in the world. It is located in the country of Nepal. It is 8,848 meters tall. This means it is just over five-and-a-half miles in height. Until 1953, nobody had successfully climbed Mount Everest, though many had tried. Mount Everest has steep slopes. Many climbers have slipped and fallen to their deaths. The mountain is very windy. Parts of it are covered with snow. Many mountaineers would get caught in snowstorms and be unable to climb. The mountain is rocky. Sometimes, during snowstorms, rocks would tumble down the slopes of the mountain. Any climbers trying to go up the mountain might be risking their lives. There is also very little oxygen atop Mount Everest. This is because the oxygen in the air reduces as we go higher. This means that it is difficult for climbers to breathe. The climbers usually take oxygen in cylinders to breathe. If they do take oxygen tanks, they have to carry extra weight on their backs. This slows them down. In 1953, a New Zealand-based climber, Edmund Hillary, and a Nepalese climber, Tenzing Norgay, climbed Mount Everest for the first time. They both took photographs on the peak. They then buried some sweets on the peak, as a gesture to celebrate their climb. But they ReadWorks.org · © 2014 ReadWorks®, Inc. All rights reserved. Going Up a Mountain could not stay for long, because it was windy and snowy. They soon came down. Later, many people asked Edmund Hillary and Tenzing Norgay which of them had reached the peak first. -

The Commonwealth Trans-Antarctic Expedition 1955-1958

THE COMMONWEALTH TRANS-ANTARCTIC EXPEDITION 1955-1958 HOW THE CROSSING OF ANTARCTICA MOVED NEW ZEALAND TO RECOGNISE ITS ANTARCTIC HERITAGE AND TAKE AN EQUAL PLACE AMONG ANTARCTIC NATIONS A thesis submitted in fulfilment of the requirements for the Degree PhD - Doctor of Philosophy (Antarctic Studies – History) University of Canterbury Gateway Antarctica Stephen Walter Hicks 2015 Statement of Authority & Originality I certify that the work in this thesis has not been previously submitted for a degree nor has it been submitted as part of requirements for a degree except as fully acknowledged within the text. I also certify that the thesis has been written by me. Any help that I have received in my research and the preparation of the thesis itself has been acknowledged. In addition, I certify that all information sources and literature used are indicated in the thesis. Elements of material covered in Chapter 4 and 5 have been published in: Electronic version: Stephen Hicks, Bryan Storey, Philippa Mein-Smith, ‘Against All Odds: the birth of the Commonwealth Trans-Antarctic Expedition, 1955-1958’, Polar Record, Volume00,(0), pp.1-12, (2011), Cambridge University Press, 2011. Print version: Stephen Hicks, Bryan Storey, Philippa Mein-Smith, ‘Against All Odds: the birth of the Commonwealth Trans-Antarctic Expedition, 1955-1958’, Polar Record, Volume 49, Issue 1, pp. 50-61, Cambridge University Press, 2013 Signature of Candidate ________________________________ Table of Contents Foreword .................................................................................................................................. -

Antarctic.V14.4.1996.Pdf

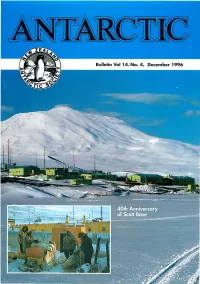

Antarctic Contents Foreword by Sir Vivian Fuchs Forthcoming Events Cover Story Scott Base 40 Years Ago by Margaret Bradshaw... Cover: Main: How Scott Base looks International today. Three Attempt a World Record Photo — Courtesy of Antarctica New Zealand Library. Solo-Antarctic Crossing National Programmes New Zealand United States of America France Australia Insert: Scott Base during its South Africa final building stage 1957. Photo — Courtesy of Guy on Warren. Education December 1996, Tourism Volume 1 4, No. 4, Echoes of the Past Issue No.l 59 Memory Moments Relived. ANTARCTIC is published quar terly by the New Zealand Antarctic Society Inc., ISSN Historical 01)03-5327, Riddles of the Antarctic Peninsula by D Yelverton. Editor: Shelley Grell Please address all editorial Tributes inquiries and contributions to the Editor, P O Box -104, Sir Robin Irvine Christchurch or Ian Harkess telephone 03 365 0344, facsimile 03 365 4255, e-mail Book Reviews [email protected]. DECEMBER 1996 Antargic Foreword By Sir Vivian Fuchs All the world's Antarcticians will wish to congratulate New Zealand on maintaining Scott Base for the last forty years, and for the valuable scientific work which has been accom plished. First established to receive the Crossing Party of the Commonwealth Trans- Antarctic Expedition 1955-58, it also housed the New Zealand P a r t y w o r k i n g f o r t h e International Geophysical Year. Today the original huts have been replaced by a more modern„. , j . , Sir andEdmund Hillaryextensive and Dr. V E.base; Fuchs join •'forces at. -

Lesson 1: Mount Everest Lesson Plan

Lesson 1: Mount Everest Lesson Plan Use the Mount Everest PowerPoint presentation in conjunction with this lesson. The PowerPoint presentation contains photographs and images and follows the sequence of the lesson. If required, this lesson can be taught in two stages; the first covering the geography of Mount Everest and the second covering the successful 1953 ascent of Everest by Sir Edmund Hillary and Tenzing Norgay. Key questions Where is Mount Everest located? How high is Mount Everest? What is the landscape like? How do the features of the landscape change at higher altitude? What is the weather like? How does this change? What are conditions like for people climbing the mountain? Who were Edmund Hillary and Tenzing Norgay? How did they reach the summit of Mount Everest? What did they experience during their ascent? What did they do when they reached the summit? Subject content areas Locational knowledge: Pupils develop contextual knowledge of the location of globally significant places. Place knowledge: Communicate geographical information in a variety of ways, including writing at length. Interpret a range of geographical information. Physical geography: Describe and understand key aspects of physical geography, including mountains. Human geography: Describe and understand key aspects of human geography, including land use. Geographical skills and fieldwork: Use atlases, globes and digital/computer mapping to locate countries and describe features studied. Downloads Everest (PPT) Mount Everest factsheet for teachers -

The Sir Edmund Hillary Foundation Kunde Hospital's 50Th Anniversary

THE SIR EDMUND HILLARY FOUNDATION OF CANADA SEPTEMBER 2016 The Sir Edmund Hillary PRESIDENT’S REPORT Foundation We began the spring of 2016 at the foundation with a trip and treks to Nepal. The objectives were multipurpose with many different projects going on under the rebuild fund which needed to be visited, as well as to check the existing projects, and also take part in the highly anticipated Celebration for the 50th Founder and Executive Director W. F. (Zeke) O’Connor Anniversary of the Kunde Hospital. (40 of those years under the support of the SEHF.) Mary and Brendan Associate Executive Director Kaye and The Canadian Rovers out of Montreal as R. Kolbuc well as myself, helped to fund raise. Zeke was able Officers to visit the hospital and take part in the celebration. K. O’Connor, President R. D. Walker, Q.C., Secretary He was lucky enough to be able to check out the K. Leung, Treasurer new heli-port which we included in the rebuild Dr. K. T. Sherpa, Senior Medical Officer project, as well as the creation of a rehabilitation Directors garden. The local Sherpas rebuild committee felt P. Crawley these were needed additions to the hospital, the heli- President, Karen O’Connor P. Gagic F. Gomez port would help save lives with speedy evacuations P. Handling and the restorative garden was added on to the P. Hillary P. Hubner rebuild program because it was felt that a tranquil P. Hull spiritual environment was desirable to help the local K. Leung N. McElhinney people and patients rehabilitate. -

Talks on Antarctica: United Nations of the World (English)

Talks on Antarctica: United Nations of the World (English) Talks on Antarctica, the United Nations of the World Topic: the great continent of ice, wind and snow located at the southernmost end of our planet, surrounded by the Southern Ocean, where the Roaring Forties and Furious Fifties rage. It is an extraordinary nature reserve, one and a half times as big as the United States, devoted to peace and science, and a continent that does not belong to a country. You do not need a passport to land on Antarctica. The great American explorer Richard E. Byrd wrote: “ I am hopeful that Antarctica in its symbolic robe of white will shine forth as a continent of peace as nations working together there in the cause of science set an example of international cooperation”. Therefore: the true United Nations of Earth are down there, on the white continent where the South Pole is found. On 28 October 2016, the creation of the Ross Sea Marine Reserve in Antarctica was announced. It is the largest in the world (one and a half times the size of Europe): the international community has finally become aware of the need to protect the valuable Antarctic marine ecosystems. The Agreement will enter into force on December 1st 2017. WHY ANTARCTICA? 1) The continent is entirely devoted “to peace and science” (Madrid Protocol). It is a nature reserve which does not belong to any country, and is a world heritage site. Researchers and logistics technicians from several different countries work together in peace in Antarctica: 5,000 during the austral summer, and 1,000 in the winter. -

CLIMBING the POLE: EDMUND HILLARY and the TRANS–ANTARCTIC EXPEDITION 1955–58. John Thomson. 2010. Eccles, Norwich: Erskine P

Polar Record 48 (247): e7 (2012). c Cambridge University Press 2011. doi:10.1017/S0032247411000714 1 CLIMBING THE POLE: EDMUND HILLARY AND The book explores the interweaving of Hillary’s clandestine THE TRANS–ANTARCTIC EXPEDITION 1955–58. personal adventure ambitions with those of the greater TAE, for John Thomson. 2010. Eccles, Norwich: Erskine Press. whom he was a supporting player and subordinate to Fuchs. Hil- 144 p., illustrated, softcover. ISBN 978-1-85-297106-9. lary had successfully climbed Mt. Everest only a few years prior £15. to this expedition and there is no doubt that his celebrity profile was beneficial to have on board. At the same time, Hillary was also tasked with being the leader of New Zealand’s fledgling New books about iconic people are difficult terrain for histori- Antarctic programme and therefore already had a full plate of ans. By definition, iconic figures are popluar and adored, usually official duties. A lot of light is shone on the not-always-smooth for some truly impressive accomplishments. But they would relationship between Hillary and the Ross Sea Committee, the not be iconic if most of their significance had not already been body that oversaw New Zealand’s involvement in the TAE. The written about, dissected, and celebrated. Which means that there author also explores the relationship between Fuchs and Hillary, is not much left to be said about, for example, the genius of including some of the specifics of their communiques while Albert Einstein or the exploring skills of Roald Amundsen. But in different parts of Antarctica, as well as after the expedition one area ripe for further investigation is the personality behind when memoirs were being written. -

4Th Grade AMI Work #8 Your Child Will Have 5 Days to Complete and Return This to His/Her Teacher to Get Credit for the Day

Name:______________________________________________________ Date:_____________ 4th Grade AMI Work #8 Your child will have 5 days to complete and return this to his/her teacher to get credit for the day. If you need more time, please let the teacher know. THEME: Extreme Settings Going Up a Mountain Mount Everest is the tallest mountain in the world. It is located in the country of Nepal. It is 8,848 meters tall. This means it is just over five-and-a-half miles in height. Until 1953, nobody had successfully climbed Mount Everest, though many had tried. Mount Everest has steep slopes. Many climbers have slipped and fallen to their deaths. The mountain is very windy. Parts of it are covered with snow. Many mountaineers would get caught in snowstorms and be unable to climb. The mountain is rocky. Sometimes, during snowstorms, rocks would tumble down the slopes of the mountain. Any climbers trying to go up the mountain might be risking their lives. There is also very little oxygen atop Mount Everest. This is because the oxygen in the air reduces as we go higher. This means that it is difficult for climbers to breathe. The climbers usually take oxygen in cylinders to breathe. If they do take oxygen tanks, they have to carry extra weight on their backs. This slows them down. In 1953, a New Zealand-based climber, Edmund Hillary, and a Nepalese climber, Tenzing Norgay, climbed Mount Everest for the first time. They both took photographs on the peak. They then buried some sweets on the peak, as a gesture to celebrate their climb. -

New Dimension Media

New Dimension Media TEACHER’S GUIDE Grades 5 to 12 The First Ascent of Mt. Everest History Happened Here Series Subject Areas: Social Studies, World History Synopsis: Archival film footage and dramatic reenactments capture Edmund Hillary’s 1953 ascent to the summit of Mount Everest. Hillary and his guide, Tenzing Norgay, became the first men to reach the top of the world and return. Reenacts their final summit ascent, including the famous “Hillary Step” rock climb. Learning Objectives: Objective 1) Students will be able to describe Edmund Hillary and Tenzing Norgay’s ascent to the top of Mount Everest in 1953 Objective 2) Students will be able to describe conditions on Mount Everest Objective 3) Students will be able to recognize the hard work and determination necessary to achieve goals Vocabulary: Himalayas, Mountaineers, summit, Sherpa, expedition, summit, harrowing, triumph, endurance, monarch, knighthood, Nepal, grandeur, adventurers, goal Pre-Viewing Questions and Activities: 1) Locate Mt. Everest on a map. 2) Have a class discussion about achievements and goals. Why do we set goals for ourselves? How do you achieve goals? Ask students to share some of their goals with the class. Post-Viewing Questions and Discussion: 1) How high is Mount Everest? How does its height compare to other mountains in the world? Why have so many people attempted to climb the mountain? Why were most unsuccessful? 2) Describe the weather conditions at Mount Everest. Why is this an especially difficult climb? What challenges must mountaineers overcome on -

Sir Edmund Hillary Scholarship Programme

Sir Edmund Hillary Scholarship Programme Inspiring excellence, all-round development and leadership August 2011 From the Vice-Chancellor Special Thanks The Sir Edmund Hillary Scholarships are the University’s way Thanks to NBR New Zealand Opera, our unique partnership with NZ Opera enables of nurturing talent, whether it be in sport or the performing artistic Hillary Scholars to arts. While many of our Hillary Scholars would like to have go 'inside' their latest opera a career in their chosen Sports or Arts fi eld, it’s also important CAVALLERIA RUSTICANA & to have options when facing an uncertain future. PAGLIACCI, be involved in rehearsals and learn from We know it can be difficult juggling academic requirements, training the company members. or practice, and competition and performance, and so we have support structures in place and the capacity to be flexible with deadlines. Hillary Scholar, Dellie Dellow (above), will gain insight into NZO production management. Often Hillary Scholars find “talking out” their situation with their high performance manager or a lecturer is all they need, while at other times they may need help to negotiate their way through an issue or problem. Despite their heavy workloads, Waikato’s Hillary Scholars are succeeding. This is evidenced by the number Sir Edmund Hillary of ‘A’ grades they achieve each semester. Scholarship Programme Recently the University joined the Athlete Friendly Tertiary Network, which formalises our commitment to high performance athletes. The network is made up of tertiary institutions that adopt a set of guiding WHO CAN APPLY? principles to support New Zealand’s athletes to combine their sporting and academic aspirations. -

Remarks on Antarctica and Climate Change, in Christchurch, New Zealand September 15, 1999

Administration of William J. Clinton, 1999 / Sept. 15 current energy trajectory—which entails higher National Science and Technology Council, as consumer costs, greater regional pollution, more recommended by PCAST. The working group pronounced climate disruption, and increasing should build on the PCAST report and assess risks to energy security—is closing fast. Thus, the portfolio of programs underway in the Fed- we should act expeditiously on PCAST’s rec- eral agencies and develop a strategic vision, in- ommendations for strengthening capacities for cluding budget recommendations that can be energy technology innovation, promoting tech- considered in agency requests for FY 2001. nologies to limit energy demand and for a clean- Please commend John Holdren, the members er energy supply, and improving management of his panel, and all of PCAST for its fine report of the Federal international energy research and on this important matter. development portfolio. WILLIAM J. CLINTON As a first step, I direct you to form a working group on international energy research, develop- NOTE: This memorandum was released by the Of- ment, demonstration, and deployment under the fice of the Press Secretary on September 15. Remarks on Antarctica and Climate Change, in Christchurch, New Zealand September 15, 1999 Thank you very much. Good afternoon. Prime to fly home, and we will make the best job Minister Shipley, Burton and Anna and Ben; of it we can. and Sir Edmund Hillary and Lady Hillary; Am- bassadors Beeman and Bolger, and their wives; to Mayor Moore: Dr. Erb, Dr. Benton, Mr. Antarctica and Climate Change Mace, Dr. Colwell; to all of those who have Let me say I am particularly honored to be made our visit here so memorable: Let me here with Sir Edmund Hillary, referred to in begin on behalf of my family and my party our family as my second favorite Hillary. -

Lesson 2: Meet Mount Everest

Everest Education Expedition Curriculum Lesson 2: Meet Mount Everest Created by Montana State University Extended University and Montana NSF EPSCoR http://www.montana.edu/everest Lesson Overview: Begin to unravel the layers of Mount Everest through geography and history. Learn where Mount Everest sits in relation to the world, to Asia, and to surrounding countries. Compare Mount Everest to the highest peak in your region. Trace the routes of the first Americans, and other mountaineers of the past, who summited this peak, and plot the routes this expedition took as you learn the history of the world’s highest mountain. Objectives: Students will be able to: 1. Locate and identify Mount Everest including the two countries it straddles. 2. Locate and identify Granite Peak, the highest point in Montana (or the highest peak in your state or region). 3. Compare and contrast the geography and history of Mount Everest to Granite Peak (or the highest peak in your state or region). 4. Explain the route the first Americans took to summit Mount Everest. Vocabulary: base camp: a place used to store supplies and get ready for climbing located low on the mountain, safe from harsh weather, icefalls, avalanches and the effects of high altitude found higher on the mountain col (coal): a low point on a ridge in between two peaks, also called a “saddle” crevasse (kruh-VAS): a crack in a glacier’s surface that can be very deep and covered by snow elevation: the height of place measured from sea level glacier: a massive river of ice that moves slowly downward