Research Papers-Mechanics / Electrodynamics/Download/3239

Total Page:16

File Type:pdf, Size:1020Kb

Load more

Recommended publications

-

2017 NSTA Physics Day Tutorial

NSTA Physics Day Baltimore, MD, Friday 6 Oct 2017, Hilton Key 9 Handout: Investigating Electrostatics with an Inexpensive Electrophorus Robert A. Morse, 5530 Nevada Ave, Washington DC 20015 [email protected] NSTA Baltimore, 6 Oct 2017 Abstract: An "instrumented" version of Volta's Electrophorus is a versatile tool to explore electrostatic charging by both induction and conduction, and highlights the difference between insulators and conductors. By adding some inexpensive indicators of charge state and charge transfer, it is a useful experimental context for students to use a qualitative atomic model to account for the observed phenomena. A classroom set is readily assembled from common household/grocery store materials at very low cost, and can be used in classes from middle school through introductory college. Participants will carry out a set of activities to get familiar with the construction and use of this historically important device. Participants - up to 40. Introduction: There are several ways to electrostatically charge objects. Many students have experience with charging by contact - by rubbing things - and have a simple model in which one object takes charge from another. Many students also have experience with induced charge effects such as sticking a rubbed balloon to a wall. Very few are likely to have observed or thought about the electrostatic charging of a conductor by the process of induction. In this workshop you will have an opportunity to see how a simple atomic model and inexpensive equipment can be used to guide students to an understanding of the process of electrostatic induction, using the concept of electrical action at a distance. -

A Companion to Physics in the Enlightenment - Part 2

A Companion to Physics in the Enlightenment - part 2 Slides 3-4 give a short summary of the most important events in the history of electricity and magnetism. Slide 5. One of the chapters in De magnete by William Gilbert (1600) contains the first modern account of electrical studies. As the court physician to Queen Elisabeth Gilbert had access to her treasury. He decided to check how many different materials, including precious stones and gems, could be electrified by rubbing in the same way as amber. He provided himself with the first electroscope, a device to show the presence of electric charge on a nearby body: „Make yourself a rotating needle, versorium, of any sort of metal, three or four fingers long, pretty light, and poised on a sharp point after the manner of a magnetic pointer. Bring near to one end of it a piece of amber or a gem, lightly rubbed, polished and shining: at once the instrument revolves...” By making use of the versorium Gilbert was able to divide all studied materials into „electrics” (those which could be electrified by rubbing), and „non-electrics”. He introduced these terms by taking example of the Greek name for amber - ήλεκτρον. He also recognized several differences between magnetic and electric interactions. e.g. that lodestone attracts only iron whereas amber acts on many kinds of bodies, that the magnet attracts only towards its poles, amber - everywhere, that the magnet pulls heavier weights than amber can. Slide 6 shows several examples of early graphic representation of magnetic field; the concept of the field did not yet exist. -

39 Electroscope

Electroscope An electroscope is an early scientific instrument that is used to detect the presence of electric charge on an object. It was the first electrical measuring instrument ever created. The first electroscope was a pivoted needle called the versorium. It was invented by William Gilbert around 1600 AD. The pith-ball electroscope and the gold-leaf electroscope are two classical types of electroscopes that are still used in modern classrooms to demonstrate the principles of static electricity. Pith-ball Electroscope The pith-ball electroscope was invented by John Canton in 1754. It consists of a small ball of some lightweight nonconductive substance, originally pith (tissue from the stems of some plants), suspended by a silk thread from the hook of an insulated stand. In order to test an object for charge, the object is brought close to the uncharged pith ball. If the object is charged, the pith ball will be attracted to it. The attraction occurs because of induced polarization of the charges inside the pith ball. For example, if a positively charged object is brought near the ball, the negative electrons in the ball will move closer to the object. Thus, the side of the ball closest to the object will be more negative, while the side farthest from the object will be more positive. Since the negative side of the ball is closer to the object than the positive side, there will be an overall attraction of the ball to the object. The pith ball can be charged by touching it to a charged object. When charged in such a way, the ball acquires the same charge as the object that is used to charge it. -

Franklin and Electricity By

Franklin and Electricity An Honors Thesis (HONRS499) By Elizabeth Cougill Thesis Advisor Dr. Abel Alves Ball State University Muncie, IN May 2005 May 7, 2005 Abstract The basis of any knowledge is what came before, and in order to understand a complex idea you must fIrst understand the basics. The basics of electricity were primarily discovered by the observations of Benjamin Franklin, who is largely publicly known for his diplomatic works. To know where Franklin's work began, 1 looked at the life of Franklin before he began work on electricity and the work done in electricity before Franklin began his work. Then 1 looked at Franklin's experiments through his own writings to discover what is said to be the foundation of modem electric physics. Acknowledgements -I want to thank Dr. Abel Alves for advising me through this project. He was patient and pointed me in the correct direction with my research. -I would also like to thank Kane Leal and Belinda Cougill, who helped me with the editing and proofreading my paper. -The Physics and Astronomy Department is also to be thanked, for their work in helping me to understand advanced electrics and inspiring me to look into the history of electrics. 1 The interests of a child can grant insight into the kind of person that they will grow up to be. This is definitely the case for Benjamin Franklin, who grew up to be a leading scientist and diplomat for the emerging United States of America. Although his personal writings do not discuss much of his early life, other sources can provide a hasic look at his early years. -

Yilliax Gilbert's Sciehtfic Ache5vekeht Ah Assessxeht

YILLIAX GILBERT'S SCIEHTFIC ACHE5VEKEHT AH ASSESSXEHT OF HIS KAGMETIC, ELECTRICAL AID COSMOLOGICAL RESEARCHES Ingo Dietrich Evers Thesis submitted for the Degree of Ph.D. University of London, London School of Economics and Political Science Department of Philosophy and Scientific Method, January, 1991 - 1 - UMI Number: U052593 All rights reserved INFORMATION TO ALL USERS The quality of this reproduction is dependent upon the quality of the copy submitted. In the unlikely event that the author did not send a complete manuscript and there are missing pages, these will be noted. Also, if material had to be removed, a note will indicate the deletion. Dissertation Publishing UMI U052593 Published by ProQuest LLC 2014. Copyright in the Dissertation held by the Author. Microform Edition © ProQuest LLC. All rights reserved. This work is protected against unauthorized copying under Title 17, United States Code. ProQuest LLC 789 East Eisenhower Parkway P.O. Box 1346 Ann Arbor, Ml 48106-1346 T Hx:S£E S F 69/| Abstract The thesis aims at a more detailed and comprehensive evaluation of Gilbert's magnetic, electrical and cosmological work than has been carried out so far and at correction of important errors in its earlier historical and methodological assessments. The latter concern the general approach to Gilbert, who has, for example, been seen as a 'natural magician', but also specific mistakes such as the widely held view that his conception of magnetic action amounted to an effluvia! theory or that he held magnetic forces to be paramount in the universe. Some historians have claimed that Gilbert's most important observations are theory-laden to the detriment of his results. -

Chapter 6 Introduction to Chapter 6 Electricity Electricity Is Everywhere Around Us

3 Electricity and Magnetism Chapter 6 Introduction to Chapter 6 Electricity Electricity is everywhere around us. We use electricity to turn on lights, cool our homes, and run our TVs, radios, and portable phones. There is electricity and in lightning and in our bodies. Even though electricity is everywhere, we can’t easily see what it is or how it works. In this chapter, you will learn the basic ideas of electricity. You will learn about electric circuits and electric Electric charge, the property of matter responsible for electricity. Investigations for Chapter 6 Circuits 6.1 What Is a Circuit? What is an electric circuit? Can you make a bulb light? In this Investigation, you will build and analyze a circuit with a bulb, battery, wires, and switch. You will also learn to draw and understand diagrams of electric circuits using standard electrical symbols. 6.2 Charge What is moving through a circuit? In this Investigation, you will create two kinds of static electricity and see what happens when the two charges come together. During the Investigation, you will also demonstrate that there only two kinds of charge. 105 Chapter 6: Electricity and Electric Circuits Learning Goals In this chapter, you will: ! Build simple circuits. ! Trace circuit paths. ! Interpret the electric symbols for battery, bulb, wire, and switch. ! Draw a circuit diagram of a real circuit. ! Explain why electrical symbols and circuit diagrams are useful. ! Explain how a switch works. ! Identify open and closed circuits. ! Charge pieces of tape and observe their interactions with an electroscope. ! Identify electric charge as the property of matter responsible for electricity. -

Lab: Making an Electroscope CHAPTER 32: ELECTROSTATICS

Name ________________________________________ Date ______________ Period ______ Lab: Making an Electroscope CHAPTER 32: ELECTROSTATICS Introduction : An ELECTROSCOPE is an instrument for detecting differences of electric potential and hence electrification. The earliest form of scientific electroscope was the versorium or electrical needle of William Gilbert (1544-1603). It consisted simply of a light metallic needle balanced on a pivot like a compass needle. Gilbert employed it to prove that numerous other bodies besides amber are susceptible of being electrified by friction. In this case the visible indication consisted in the attraction exerted between the electrified body and the light pivoted needle which was acted upon. The next improvement was the invention of simple forms of repulsion electroscope. Two similarly electrified bodies repel each other. Abraham Bennet invented the modern form of gold-leaf electroscope. Inside a glass shade he fixed to an insulated wire a pair of strips of gold-leaf. The wire terminated in a plate or knob outside the vessel. When an electrified body was held near or in contact with the knob, repulsion of the gold leaves ensued. In this lab you will be constructing and experimenting with your own electroscope using some simple materials. Materials: 1. Glass Jar with large mouth (biological specimen jar w/ non-metalic lid) 2. 15 cm rigid copper wire (10 gauge sheathed) 3. wire strippers 4. 3 cm of thin copper wire (solid) 5. aluminum foil (heavy duty) 6. straight pin 7. hot glue gun 8. Glass and acrylic rod 9. wool or flannel cloth 10. Silk cloth Proceedure : PART 1: MAKING ELECTROSCOPE 1. -

Plato 1578 Planck 1900 Rousseau 1755 Spinoza 1670 & 1677 Thoreau 1854 Voltaire 1759 Wittgenstein 1921, 1922 & 1953 Wollstonecraft 1792

ATHENA RARE BOOKS CATALOG 17 Thirty High Points in the HISTORY of IDEAS The books are in this catalog are listed in CHRONOLOGICAL ORDER (use the key below to locate individual authors) [Anon] 1776 Bayle 1697 Beauvoir 1949 Berkeley 1710 Emerson 1841 / 1844 Darwin 1860 Gilbert 1600 Hegel 1821 Hobbes 1651 Hume 1748 James 1907 Kant 1787 Locke 1690 Mill 1859 & 1869 Montesquieu 1748 Newton 1714 Nietzsche 1886 & 1887 Plato 1578 Planck 1900 Rousseau 1755 Spinoza 1670 & 1677 Thoreau 1854 Voltaire 1759 Wittgenstein 1921, 1922 & 1953 Wollstonecraft 1792 1578 The STEPHANUS Edition of Plato in a Lovely 3-Volume Binding The Book That Established the UNIVERSAL REFERENCE System for Plato’s Writings PLATO. Platonis opera quae extant omnia. (The Complete Works of Plato) [Title in Greek], Henr. Stephani, [Geneva], 1578. Volume 1: TP + [i]-[vi] = Dedication to Queen Elizabeth + [vii]-[xxii] = Studioso Lectori + [xxiii]-[xxix] = Platone Epigrammata + [xxx]-[xxi] = Catalogus Dialogorum + half title (with first page of text – unnumbered – on the verso) + 1-469 + 471 + 471-542. Volume 2: Half-title + [i]-[v] = Dedication to King James the Sixth of Scotland (later James the First of England) + [vi] = Two Poems + blank leaf [lettered AA.i.] + 3-701 + 672-673 + 704-953 + 949-950 + 956-992. Volume 3: Half-title + [i]-[v] = Dedication to the Republic of Bern + [vi] = Poem + [vii] = Contents Page + 3-48 + 47 + 50-374 + 375 + 368 + 377-416 + 1-139; Folio (14" x 9.25"). First Complete Greek/Latin Edition. $ 12,000 "A great Renaissance author and scholar as well as a member of one of Europe's most illustrious families of printers, Henri Estienne II himself edited his grand Plato, for which he commissioned a new Latin translation by Jean de Serres. -

How Electricity Was Discovered and How It Is Related to Cardiology

Arch Cardiol Mex. 2012;82(3):252---259 www.elsevier.com.mx HISTORY OF CARDIOLOGY How electricity was discovered and how it is related to cardiology Alfredo de Micheli-Serra ∗, Pedro Iturralde-Torres, Raúl Izaguirre-Ávila National Institute of Cardiology Ignacio Chávez, Mexico City, Mexico Received 30 May 2012; accepted 10 June 2012 KEYWORDS Abstract We relate the fundamental stages of the long road leading to the discovery of elec- Magnetism; tricity and its uses in cardiology. The first observations on the electromagnetic phenomena Common electricity; were registered in ancient texts; many Greek and Roman writers referred to them, although Animal electricity; they provided no explanations. The first extant treatise dates back to the XIII century and was Electrometers; written by Pierre de Maricourt during the siege of Lucera, Italy, by the army of Charles of Anjou, Electrophysiology; French king of Naples. There were no significant advances in the field of magnetism between Electrocardiography; the appearance of this treatise and the publication of the study De magnete magneticisque Mexico corporibus (1600) by the English physician William Gilbert. Scientists became increasingly inter- ested in electromagnetic phenomena occurring in certain fish, i.e., the so-called electric ray that lived in the South American seas and the Torpedo fish that roamed the Mediterranean Sea. This interest increased in the 18th century, when condenser devices such as the Leyden jar were explored. It was subsequently demonstrated that the discharges produced by ‘‘electric fish’’ were of the same nature as those produced in this device. The famous ‘‘controversy’’ relating to animal electricity or electricity inherent to an animal’s body also arose in the second half of the 18th century. -

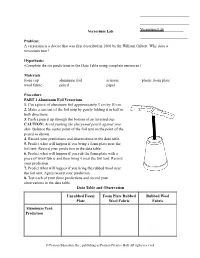

The Versorium Move? (Think About Charges and Electrons.) ______

_________________________ ! _________________________ Versorium Lab Versorium Lab__________ ! ________________________ Problem: A versorium is a device that was first described in 1600 by Sir William Gilbert. Why does a !versorium turn? Hypothesis: !(Complete the six predictions in the Data Table using complete sentences.) Materials foam cup aluminum foil scissors plastic foam plate !wool fabric pencil paper Procedure PART 1 Aluminum Foil Versorium 1. Cut a piece of aluminum foil approximately 3 cm by 10 cm. 2. Make a tent out of the foil strip by gently folding it in half in both directions. 3. Push a pencil up through the bottom of an inverted cup. CAUTION: Avoid pushing the sharpened pencil against your skin. Balance the center point of the foil tent on the point of the pencil as shown. 4. Record your predictions and observations in the data table. 5. Predict what will happen if you bring a foam plate near the foil tent. Record your prediction in the data table. 6. Predict what will happen if you rub the foam plate with a piece of wool fabric and then bring it near the foil tent. Record your prediction. 7. Predict what will happen if you bring the rubbed wool near the foil tent. Again record your prediction. 8. Test each of your three predictions and record your observations in the data table. ! Data Table and Observation Unrubbed Foam Foam Plate Rubbed Rubbed Wool Plate Wool Fabric Fabric Aluminum Tent: ! Prediction ! ! ! ! © Pearson Education, Inc., publishing as Pearson Prentice Hall. All rights reserved. Aluminum Tent: ! Observation ! ! ! ! PART 2 Paper Tent Versorium 9. What do you think would happen if you used a paper tent versorium instead of the aluminum foil? Record your prediction for each of the three tests. -

Electroscope Ñ Cardboard Ñ Pencil William Gilbert Used a Device Called a Ñ Scissors Versorium to Test an Object’S Charge

Project from Explore Electricity! With 25 Great Projects ACTIVITY! MAKE YOUR OWN SUPPLIES Ñ medium glass jar Electroscope Ñ cardboard Ñ pencil William Gilbert used a device called a Ñ scissors versorium to test an object’s charge. You can Ñ large, metal paperclip make a similar device to see static electricity Ñ modeling clay at work. Ñ aluminum foil 1 Flip the jar over onto the cardboard. Use Ñ ruler your pencil to trace around the top. Cut the Ñ white glue circle out. This will be your jar’s lid. Ñ tape Ñ 2 Open up and straighten the paperclip balloon until it looks like the letter L. Ñ wool blanket Ñ science journal 3 Carefully poke the paperclip into the lid and slide it through until about 1½ inches (3½ centimeters) of the top of the L is above the lid. The part with the right angle will be on the bottom. 4 Use a small piece of modeling clay on top of the lid to keep the wire in place. 5 Crumble a piece of aluminum foil into a ball that’s a little bit smaller than a golf ball. Push it onto the wire that’s above the lid. Be careful not to let the ball touch the cardboard. 6 Cut a piece of foil that is 3½ by ½ inches (about 9 by 1 centimeters). Fold it in half and drape it over the bent part of the wire so that it hangs below the lid. Use a small drop of glue under the fold to hold the foil in place. -

Electricity and Magnetism Demonstration Manual

PHYSICS E&M LECTURE DEMONSTRATIONS (faculty edition) Colleagues, In order to facilitate the use of the electromagnetic lecture demonstrations in the department, Professors Katrin Becker, Melanie Becker and Wayne Saslow have provided detailed descriptions of what to do, how they work, and the principles involved. Their work has been incorporated into my original 2010 Electricity and Magnetism Demonstration Manual. If you are interested in using one of these demonstrations in your classroom, you may send me an email with your class information and the demonstration number and name. Please allow at least two class days notice for the demonstration requests. In cases of shorter notice, your request will still be taken but possible conflicts may prevent it from being set up (for that particular class time). v 5 Santos Ramirez MPO Coordinator - - Physics Lecture Demonstration Program - - 200 Level Physics Teaching Laboratory Program Member - - Physics 208-218 Teaching Team Department of Physics and Astronomy Texas A&M University College Station, TX 77843-4242 U.S.A. Phone: (979) 458-7918 Email: [email protected] Electricity and Magnetism E1 Electrostatics Charging by Friction -- Triboelectricity E1-01 PRODUCING ELECTROSTATIC CHARGES E1-02 USING A CHARGE ON A ROD TO MOVE A COKE CAN E1-03 ELECTROSTATIC FORCE IN MOVING A WOOD BOARD E1-04 VAN DE GRAAFF GENERATOR E1-05 VAN DE GRAAFF GENERATOR WITH PIE PANS E1-06 DUAL VAN DE GRAAFF GENERATORS WITH STREAMERS E1-07 WIMSHURST GENERATOR AND FRANKLIN’S BELLS** E1-08 FLUX MODEL E1-09 EQUIPOTENTIAL