Igor Martinache Paris-Diderot University

Total Page:16

File Type:pdf, Size:1020Kb

Load more

Recommended publications

-

International Student Guide Welcome !

International Student guide www.univ-paris-diderot.fr Welcome ! Dear students from around the world, You have decided to come and study at Université Paris Diderot, the only multi-disciplinary university in Paris. Each year, around 6,000 foreign students register with Université Paris Diderot either individually or in the context of a mobility programme. To make your arrival and integration within the university easier, we suggest that you start by preparing for the various administrative and educational formalities awaiting you before and after your arrival, not to mention the many services available on the university campus, now. This guide is at your disposal to assist you in passing your courses at Université Paris Diderot. The International relations office Welcome to Université Paris Diderot pg. 5 Living in Paris pg. 31 Presentation of Université Paris Diderot Administrative formalities • A bit of background pg. 6 • Visas and residence permits pg. 32 • Courses pg. 8 • Social and medical cover pg. 35 • Foreign students pg. 9 • International relations office (BRI) pg. 9 Financing your programme • Grants from the French government pg. 38 Study organisation • Specific programmes pg. 39 • The LMD reform pg.10 • CROUS (Student services) grants from pg. 40 the Ministry of National Education (MEN) • The European Credit Transfer pg. 11 System (ECTS) Contents • The university calendar pg. 12 Working in France • Legislation pg. 41 How to register • Job vacancies pg. 43 • Registration at the university pg. 13 • Students registering individually pg. 14 Accommodation • Students on mobility programmes p. 24 • Types of accommodation pg. 44 • Financial assistance for housing pg. 51 Learning French • Intensive course in French language pg. -

CURRICULUM VITAE Nicolas Chevalier, Born 26Th of January 1983, French

CURRICULUM VITAE Nicolas Chevalier, born 26th of January 1983, French EDUCATION 2007 – 2010 PhD in Physics, Pierre & Marie Curie University, Saclay, France, top honors Thesis in experimental biophysics: « The influence of organic surfaces on the heterogeneous nucleation of calcium carbonate », under the supervision of Dr. P. Guenoun, LIONS laboratory, CEA Saclay. 2001 – 2006 M.S. in Physics, Swiss Federal Institute of Technology, EPFL, Lausanne, Switzerland Thesis work: modeling of crystal growth in gels, Prof. M. Droz, University of Geneva. 2003 – 2004 Lomonossov State University (MSU), Physics Faculty, Russia. 3rd Year abroad 2000 Scientific Baccalaureate, Lycée Français de Vienne, Austria, with top honors WORK EXPERIENCE 2016 – CNRS CR2 Researcher, Biophysics & Physical Embryology Laboratoire Matière Systèmes Complexes (MSC), Paris Diderot University, France Together with my collaborators, I Demonstrated that the first digestive movements in the embryo are due to mechanosensitive smooth muscle calcium waves and that they drive the anisotropic morphogenesis of the intestine. I developed the first robust protocol to grow embryonic intestinal explants in culture. Demonstrated key roles of the enteric nervous system in coordinating contractions of longitudinal and circular smooth muscle layers, giving rise to peristaltic transport. I demonstrated how the pressure-sensitive reflex of the intestine arises during embryonic development by asymmetric mechanosensitive neural inhibition of the smooth muscle layer. Revealed a nematic orientation phase transition of neurons in the developing mouse gut, driven by extracellular matrix (second harmonic generation microscopy). Developed novel methods to quantify the biophysical frictional properties of hair fibers, and elaborated a method to produce hydrophobic powders with important industrial applications. Collaborated with biologists to quantify intestinal motility in a desmin KO mouse model (A. -

Determinants of Home Parenteral Nutrition Dependence and Survival of 268 Patients with Non-Malignant Short Bowel Syndrome

Clinical Nutrition 32 (2013) 368e374 Contents lists available at SciVerse ScienceDirect Clinical Nutrition journal homepage: http://www.elsevier.com/locate/clnu Original article Determinants of home parenteral nutrition dependence and survival of 268 patients with non-malignant short bowel syndrome Aurelien Amiot a,c, Bernard Messing a,c, Olivier Corcos a,c, Yves Panis b,c, Francisca Joly a,c,* a Department of Gastroenterology and Nutrition Support, PMAD, Beaujon Hospital, APHP, Clichy, France b Department of Colorectal Surgery, PMAD, Beaujon Hospital, APHP, Clichy, France c Paris Diderot University, Paris, France article info summary Article history: Background & aims: Short bowel syndrome (SBS) is a rare and severe condition where home parenteral Received 9 April 2012 nutrition (HPN) dependence can be either permanent or transient. The timing of HPN discontinuation Accepted 13 August 2012 and the survival, according to SBS characteristics, need to be further reported to help plan pre-emptive intestinal transplantation and reconstructive surgery. Keywords: Methods: 268 Non-malignant SBS patients have been followed in our institution since 1980. HPN Short bowel syndrome dependence and survival rate were studied with univariate and multivariate analysis. Home parenteral nutrition Results: Median follow-up was 4.4 (0.3e24) years. Actuarial HPN dependence probabilities were 74%, Intestinal adaptation 64% and 48% at 1, 2 and 5 years, respectively. In multivariate analysis, HPN dependence was significantly decreased with an early (<6 mo) plasma citrulline concentration >20 mmol/l, a remaining colon >57% (4/7) and a remnant small bowel length >75 cm. Among the 124 patients who became HPN independent, 26.5% did so more than 2 years after SBS constitution. -

Efficacy of Online Nutritional Coaching in Patients with Type 2 Diabetes and Abdominal Obesity

Wednesday, November 8, 2017 Press release Efficacy of online nutritional coaching in patients with type 2 diabetes and abdominal obesity A study coordinated by Dr. Boris Hansel and Prof. Ronan Roussel, from the Diabetes- Endocrinology and Nutrition Department at Hôpital Bichat – Claude-Bernard, AP-HP and the Cordeliers Research Center (Inserm/Pierre and Marie Curie University, Paris Diderot, Paris Descartes University) shows that online nutritional coaching -an automated nutritional support program- improves dietary habits and glycemic control in patients with type 2 diabetes and abdominal obesity. These results were published in the Journal of Medical Internet Research, JMIR on November 8, 2017. Several nutritional coaching offers (personal support) have appeared on the internet in recent years, particularly in France. Whether a passing craze or a genuine revolution in nutritional management methods, online coaching is emerging as part of the treatment of chronic disorders. It is now being tested in certain hospitals, such as Hôpital Bichat-Claude Bernard, AP-HP, in order to achieve online support practically comparable to face-to-face contact. Eating a balanced diet and taking appropriate regular physical exercise are the basis for treating type 2 diabetes and excess weight. However, for many diabetics, these recommendations are difficult to apply in the long term due to the lack of specific guidance in determining where efforts should be focused. While online support tools have been shown, in certain cases, to be effective, no French studies have tested online nutritional coaching to date, particularly for diabetes and/or abdominal obesity, in terms of reducing calorie intake and increasing physical exercise, resulting in weight loss similar to that achieved through hospital follow-up. -

1 Appendix 6: Comparison of Year Abroad Partnerships with Our

Appendix 6: Comparison of year abroad partnerships with our national competitors Imperial College London’s current year abroad exchange links (data provided by Registry and reflects official exchange links for 2012-131) and their top 5 competitors’ (based on UCAS application data) exchange links are shown below. The data for competitors was confirmed either by a member of university staff (green) or obtained from their website (orange). Data was supplied/obtained between August and October 2012. Aeronautics Imperial College London France: École Centrale de Lyon, ENSICA – SupAero Germany: RWTH Aachen Singapore: National University of Singapore USA: University of California (Education Abroad Program) University of Cambridge France: École Centrale Paris Germany: Tech. University of Munich Singapore: National University of Singapore USA: Massachusetts Institute of Technology University of Oxford USA: Princeton University of Bristol Australia: University of Sydney Europe University of Southampton France: ESTACA, ENSICA – SupAero, DTUS – École Navale Brest Germany: University of Stuttgart Spain: Polytechnic University of Madrid Sweden: KTH University of Manchester Couldn’t find any evidence Bioengineering Imperial College London Australia: University of Melbourne France: Institut National Polytechnique de Grenoble Netherlands: TU Delft Singapore: National University of Singapore Switzerland: ETH Zurich USA: University of California (Education Abroad Program) University of Cambridge France: École Centrale Paris Germany: Tech. University of Munich -

Academic Bulletin for Paris, France 2018-19

Academic Bulletin for Paris, France: 2018-19 Page 1 of 21 (5/15/18) Academic Bulletin for Paris, France 2018-19 Introduction The Academic Bulletin is the CSU International Programs (IP) “catalog” and provides academic information about the program in Paris, France. CSU IP participants must read this publication in conjunction with the Academic Guide for CSU IP Participants (also known as the “Academic Guide”). The Academic Guide contains academic policies which will be applied to all IP participants while abroad. Topics include but are not limited to CSU Registration, Enrollment Requirements, Minimum/Maximum Unit Load in a Semester, Attendance, Examinations, Assignment of Grades, Grading Symbols, Credit/No Credit Option, Course Withdrawals and other policies. The Academic Guide also contains information on academic planning, how courses get credited to your degree, and the academic reporting process including when to expect your academic report at the end of your year abroad. To access the Academic Guide, go to our website here and click on the year that pertains to your year abroad. For general information about the Paris Program, refer to the CSU IP website under “Programs”. Academic Program Information The International Programs is affiliated with Mission Interuniversitaire de Coordination des Échanges Franco-Américains (MICEFA), the academic exchange organization of the cooperating institutions of the Universities of Paris listed below. Institut Catholique de Paris (ICP) Sorbonne Université (formerly Université Pierre-et-Marie- Institut -

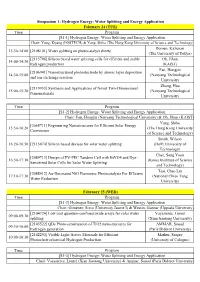

Water Splitting and Energy Application

Simposium 1: Hydrogen Energy: Water Splitting and Energy Application February 24 (TUE) Time Program [S1-1] Hydrogen Energy: Water Splitting and Energy Application Chair: Yong, Kijung (POSTECH) & Yang, Shihe (The Hong Kong University of Science and Technology) Domen, Kazunari 13:30-14:00 [2108101] Water splitting on photocatalyst sheets (The University of Tokyo) [2113796] Silicon based water splitting cells for efficient and stable Oh, Jihun 14:00-14:30 hydrogen production (KAIST) Fan, Hongjin [2106941] Nanostructured photoelectrode by atomic layer deposition 14:30-15:00 (Nanyang Technological and ion exchange reaction University) Zhang, Hua [2119953] Synthesis and Applications of Novel Two-Dimensional 15:00-15:30 (Nanyang Technological Nanomaterials University) Time Program [S1-2] Hydrogen Energy: Water Splitting and Energy Application Chair: Fan, Hongjin (Nanyang Technological University) & Oh, Jihun (KAIST) Yang, Shihe [2065711] Engineering Nanostructures for Efficient Solar Energy 15:50-16:20 (The Hong Kong University Conversion of Science and Technology) Smith, Wilson 16:20-16:50 [2115074] Silicon based devices for solar water splitting (Delft University of Technology) Chae, Sang Youn [2089713] Design of PV-PEC Tandem Cell with BiVO4 and Dye- 16:50-17:10 (Korea Insititute of Science Sensitized Solar Cells for Solar Water Splitting and Technology) Tsai, Chao Lin [2088912] Au-Decorated NiO Plasmonic Photocatalysts For Efficient 17:10-17:30 (National Chiao Tung Water Reduction University) February 25 (WED) Time Program [S1-3] Hydrogen -

Partner Universities in Europe and Middle East

Partner Institutions as of February 2018 Partner Universities in Europe and Middle East Aarhus University Denmark (2) University of Southern Denmark Helsinki Metropolia University Finland (2) University of Vaasa Burgundy School of Business Lumiere University of Lyon 2 Lyon Institute of Political Studies Normandy Business School France (8) Paris Diderot University (Paris 7) Saint-Germain-en-Laye Institute of Political Science University of Lille University of Montpellier European University Viadrina FAU Erlangen Nurnberg Heinrich Heine University Dusseldorf HTW Berlin Germany (8) Johannes Gutenberg University Mainz Ruhr-University Bochum University of Augsburg University of Regensburg Iceland (1) University of Iceland Europe Ireland (1) Dublin City University Ca' Foscari University of Venice Italy (2) University of Parma Latvia (1) University of Latvia Hague University of Applied Sciences Netherland (3) Hanze University of Applied Sciences Radboud University Nijmegen Norwegian University of Science and Technology Norway (2) University of Oslo Cracow University of Economics Poland (2) University of Lodz Spain (1) Pompeu Fabra University Linkoping University Sweden (2) Linnaeus University Cardiff University Keele University SOAS University of London U.K. (7) University of Edinburgh University of Leicester University of Manchester University of Stirling Middle East Turkey (1) Kocaeli University Partner Universities in Asia and Oceania Fudan University Jilin University Shanghai Jiao Tong University China (6) Sichuan University Soochow University -

Universities Approved for the National Postgraduate Scholarship Program: Academic Year 2017/18

Universities approved for the National Postgraduate Scholarship program: academic year 2017/18 POSITION IN SHANGHAI ARWU LEAGUE TABLE 2016 STUDY DESTINATION UNIVERSITY NAME 1 USA Harvard University 2 USA Stanford University 3 USA University of California, Berkeley 4 UK University of Cambridge 5 USA Massachusetts Institute of Technology (MIT) 6 USA Princeton University 7 UK University of Oxford 8 USA California Institute of Technology 9 USA Columbia University 10 USA University of Chicago 11 USA Yale University 12 USA University of California, Los Angeles 13 USA Cornell University 14 USA University of California, San Diego 15 USA University of Washington 16 USA Johns Hopkins University 17 UK University College London 18 USA University of Pennsylvania 19 Switzerland Swiss Federal Institute of Technology in Zurich 20 Japan University of Tokyo 21 USA University of California, San Francisco Imperial College London (formerly known and referred to in Shanghai ARWU 2016 as 22 UK The Imperial College of Science, Technology and Medicine) 23 USA University of Michigan-Ann Arbor 23 USA Washington University in St. Louis 25 USA Duke University 26 USA Northwestern University 27 Canada University of Toronto 28 USA University of Wisconsin - Madison 29 USA New York University 30 Denmark University of Copenhagen 30 USA University of Illinois at Urbana-Champaign 32 Japan Kyoto University 33 USA University of Minnesota, Twin Cities 34 Canada University of British Columbia 35 UK University of Manchester 35 USA University of North Carolina at Chapel Hill 37 -

Thrombus Composition in Sudden Cardiac Death from Acute ଝ

G Model 1 RESUS 7068 1–7 ARTICLE IN PRESS Resuscitation xxx (2017) xxx–xxx Contents lists available at ScienceDirect Resuscitation jo urnal homepage: www.elsevier.com/locate/resuscitation 2 Clinical paper 3 Thrombus composition in sudden cardiac death from acute ଝ 4 myocardial infarction a,∗ a a b 5 Q2 Johanne Silvain , Jean-Philippe Collet , Paul Guedeney , Olivier Varenne , c a d 6 Chandrasekaran Nagaswami , Carole Maupain , Jean-Philippe Empana , d d e a 7 Chantal Boulanger , Muriel Tafflet , Stephane Manzo-Silberman , Mathieu Kerneis , a a c d 8 Delphine Brugier , Nicolas Vignolles , John W. Weisel , Xavier Jouven , a d 9 Gilles Montalescot , Christian Spaulding a 10 Q3 Sorbonne Université – Univ Paris 06 (UPMC), ACTION Study Group, INSERM UMRS 1166, Institut de Cardiologie, Hôpital Pitié-Salpêtrière (AP-HP), Paris, 11 France b 12 Cardiology Department, Cochin Hospital, Paris 5 School of Medicine, Rene Descartes University, Paris, France c 13 Q4 Department of Cell and Developmental Biology, University of Pennsylvania School of Medicine, Philadelphia, PA, United States d 14 Département de cardiologie, Hôpital Européen Georges Pompidou, Université Paris Descartes, Paris Cardiovascular Research Centre (PARCC), INSERM 15 UMRS 970, Paris Sudden Death Expertise Centre, Paris, France e 16 Cardiology Department, Inserm U942, Lariboisiere Hospital, Paris Diderot University, Paris, France 17 2918 a r t i c l e i n f o a b s t r a c t 19 20 Article history: Q6 Background and aim: It was hypothesized that the pattern of coronary occlusion (thrombus composition) 21 Received 29 October 2016 might contribute to the onset of ventricular arrhythmia and sudden cardiac death (SCD) in myocardial 22 Received in revised form 11 January 2017 infarction (MI). -

1000 WLU Matrix. 2019 World Leading Universities Positions by the TOP and Rank Groups

1000 WLU Matrix. 2019 World Leading Universities positions by the TOP and Rank groups TOP Country University Rank group 50 Australia Australian National University World Best 50 Australia University of Melbourne World Best 50 Australia University of Sydney World Best 50 Belgium KU Leuven World Best 50 Canada McGill University World Best 50 Canada University of British Columbia World Best 50 Canada University of Toronto World Best 50 China Peking University World Best 50 China Tsinghua University World Best 50 Germany Heidelberg University World Best 50 Germany Ludwig-Maximilians University of Munich World Best 50 Germany Technical University Munich World Best 50 Hong Kong University of Hong Kong World Best 50 Japan Kyoto University World Best 50 Japan University of Tokyo World Best 50 Switzerland EPFL Swiss Federal Institute of Technology Lausanne World Best 50 Switzerland ETH Zürich-Swiss Federal Institute of Technology Zurich World Best 50 United Kingdom Imperial College London World Best 50 United Kingdom King's College London World Best 50 United Kingdom London School of Economics and Political Science World Best 50 United Kingdom University College London World Best 50 United Kingdom University of Bristol World Best 50 United Kingdom University of Cambridge World Best 50 United Kingdom University of Edinburgh World Best 50 United Kingdom University of Manchester World Best 50 United Kingdom University of Oxford World Best 50 USA California Institute of Technology Caltech World Best 50 USA Carnegie Mellon University World Best 50 -

16 November 2020 Errata in the IPCC Special Report on the Ocean And

16 November 2020 Errata in the IPCC Special Report on the Ocean and Cryosphere in a Changing Climate (SROCC) Handled in accordance with the IPCC protocol for addressing possible errors in IPCC Assessment Reports, Synthesis Reports, Special Reports and Methodology Reports: https://www.ipcc.ch/site/assets/uploads/2018/09/ipcc_error_protocol_en.pdf Summary for Policymakers A.3.1, Line 1: Replace '1902–2015' with '1902–2010' and replace 'likely' with 'very likely' Figure SPM3.d: Replace Figure SPM3.d with Errata Figure SPM3.d. The figure has been updated to correct the lines for the transition ranges and the corresponding alignment of confidence levels B.6.2, Line 1: Insert ‘risks’ before ‘increase with further warming’ Chapter 1 Figure 1.1: Replace Figure 1.1 with Errata Figure 1.1. Panel f equation given as 'FAR = 1 – Pant / Pnat' has been corrected to read 'FAR = 1 – Pnat / Pant' Figure 1.1 Caption, Line 11: replace 'FAR = 1 – Pant / Pnat' with 'FAR = 1 – Pnat / Pant' Chapter 3 Figure 3.3: Replace Figure 3.3 with Errata Figure 3.3. The sea ice concentration trend unit ‘°C per decade’ has been corrected to read '% per decade' Chapter 4 Section 4.2.3.2, page 352, paragraph 1, line 1: Replace ‘16 cm (5–95 percentile; 2–37 cm)’ with ‘10 cm (5–95 percentile; 2–23 cm)’ Chapter 5 Figure 5.16: Replace Figure 5.16 with Errata Figure 5.16. The figure has been updated to correct the alignment of the color gradient, and associated confidence levels, to the temperature scale and the placement of the line 'Present day'.