Lili Bio-Formatted

Total Page:16

File Type:pdf, Size:1020Kb

Load more

Recommended publications

-

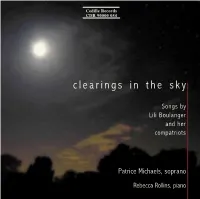

Clearings in the Sky

Cedille Records CDR 90000 054 c l e a r i n g s i n t h e s k y Songs by Lili Boulanger and her compatriots Patrice Michaels, soprano Rebecca Rollins, piano DDD Absolutely Digital™ CDR 90000 054 clearings in the sky GABRIEL FAURÉ (1845-1924) bm IV. Un poète disait . (1:44) 1 Vocalise-étude . (3:14) bn V. Au pied de mon lit . (2:23) 2 Tristesse . (2:51) bo VI. Si tout ceci n’est qu’un pauvre rêve . (2:28) 3 En prière . (2:46) bp VII. Nous nous aimerons tant . (2:49) LILI BOULANGER (1893-1918) bq VIII. Vous m’avez regardé avec toute votre âme . (1:32) 4 Reflets . (3:02) br IX. Les lilas qui avaient fleuri . (2:36) 5 Attente . (2:21) bs X. Deux ancolies . (1:20) 6 Le retour . (5:35) bt XI. Par ce que j’ai souffert . (3:01) MAURICE RAVEL (1875-1937) ck XII. Je garde une médaille d’elle . (1:59) 7 Pièce en forme de Habañera . (3:46) cl XIII. Demain fera un an . (8:42) CLAUDE DEBUSSY (1862-1918) OLIVIER MESSIAEN (1908-1992) 8 Le jet d’eau . (6:05) cm Le sourire . (1:35) LILI BOULANGER: Clairières dans le ciel (36:25) ARTHUR HONEGGER (1892-1955) 9 I. Elle était descendue au bas de la prairie . (2:00) cn Vocalise-étude . (2:11) bk II. Elle est gravement gaie . (1:47) LILI BOULANGER bl III. Parfois, je suis triste . (3:37) co Dans l’immense tristesse . (5:51) Patrice Michaels, soprano Rebecca Rollins, piano TT: (76:35) ./ Cedille Records is a trademark of The Chicago Classical Recording Foundation, a not-for-profit foundation devoted to promoting the finest musicians and ensembles in the Chicago area. -

Li-Li Boo-Lan-Jeh

Lili Boulanger Li-li Boo-lan-jeh (j is a soft g sound as in genre) Born: August 21st, 1893, Paris, France Died: March 15th, 1918, Mézy-sur-Seine, France “To study music, we must learn the rules. To create music, we must Period of Music: 20th Century, Modern break them.” – Nadia Boulanger, Lili’s beloved sister and teacher Biography: Lili Boulanger was born in 1893 in Paris, France to a musical family. Her mother, father, and sister Nadia were all trained composers or performers. When her father, Ernest, was only 20, he won the Prix de Rome. This coveted prize, which provided a year’s study in Rome, was the greatest recognition a young French composer could attain. Other winners of this prestigious award include Hector Berlioz, Gabriel Fauré, and Claude Debussy. Ernest Boulanger was 62 when he married a Russian princess. He was 72 years old when Nadia was born and 79 when Lili was born. He died when both children were still young. Lili’s immense talent was recognized early on, and at the age of 2 she began receiving musical training from her mom and eventually her older sister. In 1895 she contracted bronchial pneumonia, after which she was constantly ill. Because of her frail health, she relied entirely on private study since she was too weak to obtain a full music education at the Conservatoire. In 1913, Lili became the first woman to win the Prix de Rome for her Cantata Faust et Helene at the age of 20, the same age her father was when he won this award. -

Lili Boulanger (1893–1918) and World War I France: Mobilizing Motherhood and the Good Suffering

Lili Boulanger (1893–1918) and World War I France: Mobilizing Motherhood and the Good Suffering By Anya B. Holland-Barry A dissertation submitted in partial fulfillment of the requirements for the degree of Doctor of Philosophy (Music) at the UNIVERSITY OF WISCONSIN-MADISON 2012 Date of final oral examination: 08/24/2012 This dissertation is approved by the following members of the Final Oral Committee: Susan C. Cook, Professor, Music Charles Dill, Professor, Music Lawrence Earp, Professor, Music Nan Enstad, Professor, History Pamela Potter, Professor, Music i Dedication This dissertation is dedicated to my best creations—my son, Owen Frederick and my unborn daughter, Clara Grace. I hope this dissertation and my musicological career inspires them to always pursue their education and maintain a love for music. ii Acknowledgements This dissertation grew out of a seminar I took with Susan C. Cook during my first semester at the University of Wisconsin. Her enthusiasm for music written during the First World War and her passion for research on gender and music were contagious and inspired me to continue in a similar direction. I thank my dissertation advisor, Susan C. Cook, for her endless inspiration, encouragement, editing, patience, and humor throughout my graduate career and the dissertation process. In addition, I thank my dissertation committee—Charles Dill, Lawrence Earp, Nan Enstad, and Pamela Potter—for their guidance, editing, and conversations that also helped produce this dissertation over the years. My undergraduate advisor, Susan Pickett, originally inspired me to pursue research on women composers and if it were not for her, I would not have continued on to my PhD in musicology. -

Jessica Rivera, Soprano Kelley O'connor, Mezzo-Soprano Robert

CAL PERFORMANCES PRESENTS PROGRAM Sunday, October 13, 2013, 3pm Felix Mendelssohn (1809–1847) Volkslied (O säh ich auf der Heide dort), Hertz Hall Op. 63, No. 5 (1842) Ms. O’Connor & Ms. Rivera Jessica Rivera, soprano Mendelssohn Ich wollt, meine Lieb’ ergösse sich, Kelley O’Connor, mezzo-soprano Op. 63, No. 1 (1836) Robert Spano, piano Ms. O’Connor & Ms. Rivera Claude Debussy (1862–1918) Chansons de Bilitis (1897) PROGRAM I. La Flûte de Pan II. La Chevelure III. Le Tombeau des Naïades Camille Saint-Saëns (1835–1921) El Desdichado (1849) Ms. O’Connor Ms. O’Connor & Ms. Rivera Jonathan Leshnoff (b. 1973) Monica Songs (2012) David Bruce (b. 1970) That Time with You (2013) I. For Where Thou Go, I Will Go I. The Sunset Lawn II. We Cover Thee—Sweet Face II. That Time with You III. I thank You III. Black Dress IV. Greetings from Troy, Illinois IV. Bring Me Again V. So Much Joy World Premiere VI. There’s a Son Born to Naomi Ms. O’Connor World Premiere Ms. Rivera Federico Mompou (1893–1987) Combat del Somni (1942–1948) Gabriela Lena Frank (b. 1972) Selections from The Kitchen Songbook(2013) I. Damunt de tu només les flors II. Aquesta nit un mateix vent I. Honey III. Jo et pressentia com la mar Bay Area Premiere IV. Fes me la vida transparent II. Sofrito Ms. Rivera World Premiere Ms. O’Connor & Ms. Rivera Charles Gounod (1818–1893) La Siesta (1870) Ms. O’Connor & Ms. Rivera Funded by the Koret Foundation, this performance is part of Cal Performances’ 2013–2014 Koret Recital Series, which brings world-class artists to our community. -

The Rite of Spring

The Rite of Spring This weekend we’re afforded the opportunity to experience two seldom-heard works: Dvořák’s piano concerto and Lili Boulanger’s dark-night-of-the-soul set to music, D’un soir triste. Stravinsky’s The Rite of Spring — a watershed in the history of Western classical music — comprises the second half. ILI BOULANGER Born 21 August 1893; Paris, France Died 15 March 1918; Mézy-sur-Seine, France D’un soir triste Composed: 1918 First performance: 6 March 1921; Paris, France (chamber work), 9 May 1992; San Francisco, California (orchestral work) Last MSO performance: MSO premiere Instrumentation: 2 flutes, 2 oboes, English horn, 2 clarinets, bass clarinet, 2 bassoons, contrabassoon, 4 horns, 3 trumpets, 3 trombones, tuba, timpani, percussion (bass drum, suspended cymbals, tam tam), harp, celeste, strings Approximate duration: 9 minutes Lili Boulanger was the younger sister of the noted teacher, conductor, and composer Nadia Boulanger (1887-1979). As a child, she accompanied Nadia to classes at the Paris Conserva- toire. She later studied organ with Louis Vierne. Lili also sang and played piano, violin, cel- lo, and harp. The first woman to receive the Prix de Rome — in 1913, for her cantata Faust et Hélène — her composing life was brief but productive. Her most important works are her psalm settings and other large-scale choral pieces. Fauré admired and promoted her music. D’un soir triste (On a Sad Evening) was written in the final months of her life (often beset by illness, she died at the early age of 24), along with a shorter companion piece, D’un matin de printemps (On a Morning in Spring). -

Contextualizing Sociological Narratives and Wagnerian Aesthetics in Lili Boulanger’S Faust Et Hélène

La Victoire du péril rose: Contextualizing Sociological Narratives and Wagnerian Aesthetics in Lili Boulanger’s Faust et Hélène Master’s Thesis Presented to The Faculty of the Graduate School of Arts and Sciences Brandeis University Department of Music Eric Chafe, Advisor In Partial Fulfillment of the Requirements for the Degree Master of Fine Arts in Musicology by Julie VanGyzen May, 2014 Copyright by Julie VanGyzen © 2014 Abstract La Victoire du Péril Rose: Contextualizing Sociological Narratives and Wagnerian Aesthetics in Lili Boulanger’s Faust et Hélène A thesis presented to the Department of Music Graduate School of Arts and Sciences Brandeis University Waltham, Massachusetts By Julie VanGyzen On July 5th, 1913, the instructors of the Académie des Beau-Arts of France, the institutes responsible for the production of French artists, announced an unexpected and unprecedented victor of the distinguished Prix de Rome competition in composition. Nineteen-year-old Lili Boulanger was the new sound of French music. Never before had a woman composer won first place in the century old Prix de Rome due to the conservative political views shared by the Académie and the misogyny of the competition’s jury. This momentous event has been given much attention in the research of Boulanger’s Prix de Rome success through sociological perspective on France in 1913; a bourgeoning feminist atmosphere in the increasingly liberal government of France influenced the jury’s decision to award Boulanger the Premier Grand Prix. Contemporary English musicological scholarship has favored this socio-historical narrative over analysis the aesthetic character of her winning cantata, Faust et Hélène, thereby neglecting another significant facet to Boulanger’s win; her overt incorporation of motifs from Richard Wagner’s Tristan und Isolde. -

A Performer's Analysis of Lili Boulanger's Clairières Dans Le Ciel: Song Cycle for High Voice and Piano; a Lecture Recital

A PERFORMER’S ANALYSIS OF LILI BOULANGER’S CLAIRIÈRES DANS LE CIEL: SONG CYCLE FOR HIGH VOICE AND PIANO; A LECTURE RECITAL TOGETHER WITH THE ROLE OF BLANCHE IN DIALOGUES OF THE CARMELITES BY F. POULENC AND TWO RECITALS OF SELECTED WORKS BY H. PURCELL, F. SCHUBERT, S. PROKOFIEFF, E. CHAUSSON, W. A. MOZART, R. SCHUMANN AND G. FAURÉ Deborah Williamson, B.M., M.M., A. D. Dissertation Prepared for the Degree of DOCTOR OF MUSICAL ARTS UNIVERSITY OF NORTH TEXAS December 2001 APPROVED: Linda Di Fiore, Major Professor Cody Garner, Related Field Professor Lenora McCroskey, Committee Member Graham Phipps, Chair of Graduate Studies in College of Music James C. Scott, Dean of the College of Music C. Neal Tate, Dean of the Robert B. Toulouse School of Graduate Studies Williamson, Deborah, A Performer’s Analysis of Lili Boulanger’s Clairières dans le ciel: Song Cycle for High Voice and Piano; a Lecture Recital Together with the Role of Blanche in Dialogues of the Carmelites by F. Poulenc and Two Recitals of Selected Works by H. Purcell, F. Schubert, S. Prokofieff, E. Chausson, W. A. Mozart, R. Schumann and G. Fauré. Doctor of Musical Arts (Performance), December 2001, 71 pp., 1 table, 19 musical examples, references, 57 titles. Lili Boulanger was an important composer of early twentieth century French music. Her compositional style represents a development and mastery of musical techniques of the great composers of her time including Fauré, Debussy and Wagner combined with her own creative expression. The result is a compelling musical language that was uniquely her own. -

Program Notes by Leonard Garrison 7:30 Pm

Program Notes by Leonard Garrison 7:30 p.m., Saturday, June 7, 2014 Dance (1973) Wilke Richard Renwick Wilke Renwick (b. 1932) played horn in the Denver Symphony Orchestra for thirty-two years. His very brief Dance, the best selling piece for brass quintet ever composed, features rhythms in irregular meter patterned after Greek folk dances. Trois Chansons de Charles d’Orléans (1898, 1908) Claude Debussy Claude Debussy (1865-1918) forged a new, specifically French direction in music and eschewed traditional forms and rules of harmony. The Three Songs of Charles d'Orléans are the only a cappella choral pieces that he composed, here presented in a transcription for brass quintet. Debussy’s songs are based on poems by Charles Duc d'Orléans (1394-1465), member of the Valois branch of the French royal family and prisoner of the English during the Hundred Years’ War. Debussy’s texture strikes a balance both between homophonic (chordal) and contrapuntal writing and between Renaissance and early twentieth-century styles. “Dieu! qu'il la fait bon regarder!” (“God! But She Is Fair!”) is ethereal and subdued. “Quand j'ai ouy le tambourin” (“When I Heard the Tambourine”), is livelier, taking its rhythm from drumming patterns. “Yver, vous n'estes qu'un villain” (“Winter, You're Naught but a Rogue”) is the most dramatic, illustrating the rough treatment humans receive from winter. Pour les enfants (1999) John Harmon Moonflower (1999) [Note by John Harmon] Pour les enfants was inspired by the total dedication of Hildegard Petermann, a wonderful, old-school piano teacher in our village. -

An Original Composition, Galleria Armonica, Theme and Variations For

Louisiana State University LSU Digital Commons LSU Doctoral Dissertations Graduate School 2007 An original composition, galleria armonica, theme and variations for piano, harpsichord, harp and orchestra and a comparative study between the pedagogical methodologies of Arnold Schoenberg and Nadia Boulanger regarding training the composer Barrett Ashley Johnson Louisiana State University and Agricultural and Mechanical College Follow this and additional works at: https://digitalcommons.lsu.edu/gradschool_dissertations Part of the Music Commons Recommended Citation Johnson, Barrett Ashley, "An original composition, galleria armonica, theme and variations for piano, harpsichord, harp and orchestra and a comparative study between the pedagogical methodologies of Arnold Schoenberg and Nadia Boulanger regarding training the composer" (2007). LSU Doctoral Dissertations. 1833. https://digitalcommons.lsu.edu/gradschool_dissertations/1833 This Dissertation is brought to you for free and open access by the Graduate School at LSU Digital Commons. It has been accepted for inclusion in LSU Doctoral Dissertations by an authorized graduate school editor of LSU Digital Commons. For more information, please [email protected]. AN ORIGINAL COMPOSITION, GALLERIA ARMONICA, THEME AND VARIATIONS FOR PIANO, HARPSICHORD, HARP AND ORCHESTRA AND A COMPARATIVE STUDY BETWEEN THE PEDAGOGICAL METHODOLOGIES OF ARNOLD SCHOENBERG AND NADIA BOULANGER REGARDING TRAINING THE COMPOSER A Dissertation Submitted to the Graduate Faculty of the Louisiana State University and -

Classics 2: Program Notes Armed Forces Salute Robert Lowden Born

Classics 2: Program Notes Armed Forces Salute Robert Lowden Born in Camden, New Jersey, July 23, 1920; died in Medford, New Jersey, October 30, 1998 Composer, music educator, conductor, arranger, and trombonist Robert Lowden played in the Camden High School band and orchestra before studying music at the College of South Jersey. His studies were interrupted by World War II, during which he served as a trombonist and arranger for the 322nd Army Band at Fort Dix. After the war he resumed his studies at Temple University in Philadelphia though he was largely self-taught as an arranger. He taught in the public schools in Camden, New Jersey, and served as an arranger for Johnny Austin, Oscar Dumont, and Claude Thornhill. From 1958 to 1968 Lowden arranged for the 101 Strings Orchestra, receiving credit on their 150 plus popular music and easy-listening albums. One of the best-known arrangers for big bands, jazz ensembles, and pops orchestras, Lowden also arranged for college and high school ensembles and was in demand as an adjudicator and clinician at festivals and schools. He also composed over 400 advertising jingles, of which the most famous was probably the Melrose Diner jingle “Everybody who knows goes to the Melrose.” In his last years he also worked as an arranger for the Pennsy Pops Orchestra (Norristown, Pennsylvania) and for the Ocean City Pops (Ocean City, New Jersey). One of Lowden’s most often played arrangements is his stirring tribute to the five principal branches of the United States Armed Forces, which is played for Veteran’s Day concerts and other patriotic events across the country. -

Lili Boulanger, a 100 Años De Su Muerte

HOMENAJE Lili Boulanger, a 100 años de su muerte por Hugo Roca Joglar A Carolina Castañeda Van Waeyenberge a presencia del órgano resulta siniestra. El movimiento de sus sonidos produce una sensación de angustia; se mueven Lde formas incomprensibles: ni retroceden ni avanzan, es como si se abrieran y cerraran, pero nunca terminaran por completar la apertura o el encierro. De su existencia incierta se desprenden ideas circulares y acuáticas: suaves vibraciones surgen y desaparecen sobre la superficie de nocturna agua estancada. Dos violines y el violonchelo construyen una homófona frase compuesta por tres largas notas cuya expresión tensa y sombría precede al lamento de la mezzosoprano: “Pie Jesus Domine/dona eis requiem” (piadoso Jesús, nuestro Señor/dales descanso), resuena el canto oscuro de una mujer doliente. Lili Boulanger (1893-1918) es la primera mujer que ganó —en 1913, a los 19 años, gracias a su cantata Faust et Héléne para coro, orquesta y cantantes solistas— el Prix de Rome, máxima distinción que la monarquía francesa otorgaba a los músicos. El premio le Lili Boulanger (1893-1918) granjeó un contrato con la casa editora Ricordi (la que publicó a Rossini y a Verdi) en el que se comprometía a escribir dos óperas. triste (1918) y Pour des funérailles d’un soldat (1913) para Para la primera, guiada por el impresionismo, escogió La princesse barítono, coro y orquesta, sobre un texto de Alfred de Musset Maleine de Maurice Maeterlinck (1862-1949), obra simbolista que (1810-1857). Varias de sus obras fueron destruidas por ella, como narra la tragedia de una frágil princesa. -

SISTER ACT- NADIA & LILI BOULANGER Bible 5:4:19

Sister act: nadia & lili boulanger Born to the civilized world of fin de siècle Paris, they are legendary in the rarefied world of serious music. Everything about them was a dichotomy; Lili's life was brief and plagued with illness virtually from infancy but Juliette Nadia Boulanger ( September 16, 1887 -- October 22, 1979) lived a long and incredibly productive life to the age of 92, beginning as a composer and instructor before devoting herself solely to teaching composition at 33. For decades, she taught just about every musician you've ever heard of, particularly Americans; more than 1200 students, including: Aaron Copeland, Walter Piston and Virgil Thomson. Others include Marc Blitzstein, Burt Bacharach, Daniel Barenboim, John Eliot Gardner, Philip Glass, Ned Rorem, Gian-Carlo Menotti, Astor Piazzolla, Michel Legrand, Quincy Jones, Dinu Lipatti, Douglas Moore and Thea Musgrave to name just a few! Funnily enough, like Ravel before her, she informed George Gershwin that she had nothing to teach him. But the list is endless... and her reputation endures as one of the major forces in the annals of twentieth century musical world. Ned Rorem called her ''the most influential teacher since Socrates." Her musical influence was so ubiquitous that Virgil Thomson once said: "Every town in the USA had a five - and- dime and a Boulanger pupil." Her younger sister, Marie-Juliette Olga (always known as Lili) Boulanger lived a tragically short life: (August 21, 1893 -- March 15, 1918). She was cursed from the very beginning by chronic illness beginning with bronchial pneumonia at the age of two until her death at 24, plagued with debilitating 'intestinal tuberculosis' (retrospectively thought to have been what is now known as Crohn's Disease.) Yet within that short fragile life she became the first female in its history to win the Paris Conservatoire's prestigious Prix de Rome in her teens, leaving behind a significant body of more than a dozen major works for orchestra, instrumental soloists and chorus.