An Original Composition, Galleria Armonica, Theme and Variations For

Total Page:16

File Type:pdf, Size:1020Kb

Load more

Recommended publications

-

Apuntes Para Un Pocket Retrato De Un Compositor Transpirenaico Luis De

CORE Metadata, citation and similar papers at core.ac.uk Provided by Hedatuz Apuntes para un pocket retrato de un compositor transpirenaico Luis de Pablo en el septuagésimo año* (Notes for a pocket portrait of a composer from beyond the Pyrinees. Luis de Pablo, seventy years old) Åstrand, Hans Mästarbacken 145 S-129 49 Hägersten BIBLID [1137-4470 (2000), 12; 181-197] La posición internacional del compositor bilbaíno Luis de Pablo ya se marca por el hecho de que más de la mi - tad de sus múltiples obras se han estrenado en el extranjero – es transpirenaico, y al mismo tiempo muy español. Su influencia pedagógica ha introducido la vanguardia de postguerra en España, pero lo más esencial son sus grandes obras de carácter mundial, aludiendo también a otras culturas, así como las cuatro óperas sobre temas actuales de la sociedad española e intern a c i o n a l . Palabras Clave: Tr a n s p i renaico. Influencia pedagógica. Va n g u a rdia de postguerra. Música internacional. Cultu - ras mundiales. Operas. Temas actuales. Luis de Pabloren obra ugariaren erdia atzerrian estreinatu izanak markatzen du, garbi asko, bilbotar musikagile - a ren nazioarteko kokaera –Pirinioez haraindikoa da, eta era berean guztiz espainiarra. Haren eragin pedagogikoaren bi - dez, gerra ondoko abangoardia ezagutarazi zuen Espainian, baina harengan funtsezkoena obra unibertsal handiak dira, horietan beste kulturen aipamena ere egiten duela, bai eta Espainiako eta nazioarteko gizart e a ren egungo gaiei b u ruzko lau operak ere . Giltz-Hitzak: Pirinioez gaindikoa. Eragin pedagogikoa. Gerra ondoko abangoardia. Nazioarteko musika. Kultura nazionalak. Operak. -

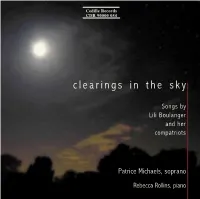

Clearings in the Sky

Cedille Records CDR 90000 054 c l e a r i n g s i n t h e s k y Songs by Lili Boulanger and her compatriots Patrice Michaels, soprano Rebecca Rollins, piano DDD Absolutely Digital™ CDR 90000 054 clearings in the sky GABRIEL FAURÉ (1845-1924) bm IV. Un poète disait . (1:44) 1 Vocalise-étude . (3:14) bn V. Au pied de mon lit . (2:23) 2 Tristesse . (2:51) bo VI. Si tout ceci n’est qu’un pauvre rêve . (2:28) 3 En prière . (2:46) bp VII. Nous nous aimerons tant . (2:49) LILI BOULANGER (1893-1918) bq VIII. Vous m’avez regardé avec toute votre âme . (1:32) 4 Reflets . (3:02) br IX. Les lilas qui avaient fleuri . (2:36) 5 Attente . (2:21) bs X. Deux ancolies . (1:20) 6 Le retour . (5:35) bt XI. Par ce que j’ai souffert . (3:01) MAURICE RAVEL (1875-1937) ck XII. Je garde une médaille d’elle . (1:59) 7 Pièce en forme de Habañera . (3:46) cl XIII. Demain fera un an . (8:42) CLAUDE DEBUSSY (1862-1918) OLIVIER MESSIAEN (1908-1992) 8 Le jet d’eau . (6:05) cm Le sourire . (1:35) LILI BOULANGER: Clairières dans le ciel (36:25) ARTHUR HONEGGER (1892-1955) 9 I. Elle était descendue au bas de la prairie . (2:00) cn Vocalise-étude . (2:11) bk II. Elle est gravement gaie . (1:47) LILI BOULANGER bl III. Parfois, je suis triste . (3:37) co Dans l’immense tristesse . (5:51) Patrice Michaels, soprano Rebecca Rollins, piano TT: (76:35) ./ Cedille Records is a trademark of The Chicago Classical Recording Foundation, a not-for-profit foundation devoted to promoting the finest musicians and ensembles in the Chicago area. -

Li-Li Boo-Lan-Jeh

Lili Boulanger Li-li Boo-lan-jeh (j is a soft g sound as in genre) Born: August 21st, 1893, Paris, France Died: March 15th, 1918, Mézy-sur-Seine, France “To study music, we must learn the rules. To create music, we must Period of Music: 20th Century, Modern break them.” – Nadia Boulanger, Lili’s beloved sister and teacher Biography: Lili Boulanger was born in 1893 in Paris, France to a musical family. Her mother, father, and sister Nadia were all trained composers or performers. When her father, Ernest, was only 20, he won the Prix de Rome. This coveted prize, which provided a year’s study in Rome, was the greatest recognition a young French composer could attain. Other winners of this prestigious award include Hector Berlioz, Gabriel Fauré, and Claude Debussy. Ernest Boulanger was 62 when he married a Russian princess. He was 72 years old when Nadia was born and 79 when Lili was born. He died when both children were still young. Lili’s immense talent was recognized early on, and at the age of 2 she began receiving musical training from her mom and eventually her older sister. In 1895 she contracted bronchial pneumonia, after which she was constantly ill. Because of her frail health, she relied entirely on private study since she was too weak to obtain a full music education at the Conservatoire. In 1913, Lili became the first woman to win the Prix de Rome for her Cantata Faust et Helene at the age of 20, the same age her father was when he won this award. -

Concert Programdownload Pdf(349

The University at Buffalo Department of Music and The Robert & Carol Morris Center for 21st Century Music present Stockhausen's Mantra For Two Pianos Eric Huebner and Steven Beck, pianos Sound and electronic interface design: Ryan MacEvoy McCullough Sound projection: Chris Jacobs and Ryan MacEvoy McCullough Saturday, October 14, 2017 7:30pm Lippes Concert Hall in Slee Hall PROGRAM Mantra (1970) Karlheinz Stockhausen (1928 – 2007) Program Note by Katherine Chi To say it as simply as possible, Mantra, as it stands, is a miniature of the way a galaxy is composed. When I was composing the work, I had no accessory feelings or thoughts; I knew only that I had to fulfill the mantra. And it demanded itself, it just started blossoming. As it was being constructed through me, I somehow felt that it must be a very true picture of the way the cosmos is constructed, I’ve never worked on a piece before in which I was so sure that every note I was putting down was right. And this was due to the integral systemization - the combination of the scalar idea with the idea of deriving everything from the One. It shines very strongly. - Karlheinz Stockhausen Mantra is a seminal piece of the twentieth century, a pivotal work both in the context of Stockhausen’s compositional development and a tour de force contribution to the canon of music for two pianos. It was written in 1970 in two stages: the formal skeleton was conceived in Osaka, Japan (May 1 – June 20, 1970) and the remaining work was completed in Kürten, Germany (July 10 – August 18, 1970). -

The-Piano-Teaching-Legacy-Of-Solomon-Mikowsky.Pdf

! " #$ % $%& $ '()*) & + & ! ! ' ,'* - .& " ' + ! / 0 # 1 2 3 0 ! 1 2 45 3 678 9 , :$, /; !! < <4 $ ! !! 6=>= < # * - / $ ? ?; ! " # $ !% ! & $ ' ' ($ ' # % %) %* % ' $ ' + " % & ' !# $, ( $ - . ! "- ( % . % % % % $ $ $ - - - - // $$$ 0 1"1"#23." 4& )*5/ +) * !6 !& 7!8%779:9& % ) - 2 ; ! * & < "-$=/-%# & # % %:>9? /- @:>9A4& )*5/ +) "3 " & :>9A 1 The Piano Teaching Legacy of Solomon Mikowsky by Kookhee Hong New York City, NY 2013 2 TABLE OF CONTENTS Preface by Koohe Hong .......................................................3 Endorsements .......................................................................3 Comments ............................................................................5 Part I: Biography ................................................................12 Part II: Pedagogy................................................................71 Part III: Appendices .........................................................148 1. Student Tributes ....................................................149 2. Student Statements ................................................176 -

Sibelius Society

UNITED KINGDOM SIBELIUS SOCIETY www.sibeliussociety.info NEWSLETTER No. 84 ISSN 1-473-4206 United Kingdom Sibelius Society Newsletter - Issue 84 (January 2019) - CONTENTS - Page 1. Editorial ........................................................................................... 4 2. An Honour for our President by S H P Steadman ..................... 5 3. The Music of What isby Angela Burton ...................................... 7 4. The Seventh Symphonyby Edward Clark ................................... 11 5. Two forthcoming Society concerts by Edward Clark ............... 12 6. Delights and Revelations from Maestro Records by Edward Clark ............................................................................ 13 7. Music You Might Like by Simon Coombs .................................... 20 8. Desert Island Sibelius by Peter Frankland .................................. 25 9. Eugene Ormandy by David Lowe ................................................. 34 10. The Third Symphony and an enduring friendship by Edward Clark ............................................................................. 38 11. Interesting Sibelians on Record by Edward Clark ...................... 42 12. Concert Reviews ............................................................................. 47 13. The Power and the Gloryby Edward Clark ................................ 47 14. A debut Concert by Edward Clark ............................................... 51 15. Music from WW1 by Edward Clark ............................................ 53 16. A -

An Exploration of the Relationship Between Mathematics and Music

An Exploration of the Relationship between Mathematics and Music Shah, Saloni 2010 MIMS EPrint: 2010.103 Manchester Institute for Mathematical Sciences School of Mathematics The University of Manchester Reports available from: http://eprints.maths.manchester.ac.uk/ And by contacting: The MIMS Secretary School of Mathematics The University of Manchester Manchester, M13 9PL, UK ISSN 1749-9097 An Exploration of ! Relation"ip Between Ma#ematics and Music MATH30000, 3rd Year Project Saloni Shah, ID 7177223 University of Manchester May 2010 Project Supervisor: Professor Roger Plymen ! 1 TABLE OF CONTENTS Preface! 3 1.0 Music and Mathematics: An Introduction to their Relationship! 6 2.0 Historical Connections Between Mathematics and Music! 9 2.1 Music Theorists and Mathematicians: Are they one in the same?! 9 2.2 Why are mathematicians so fascinated by music theory?! 15 3.0 The Mathematics of Music! 19 3.1 Pythagoras and the Theory of Music Intervals! 19 3.2 The Move Away From Pythagorean Scales! 29 3.3 Rameau Adds to the Discovery of Pythagoras! 32 3.4 Music and Fibonacci! 36 3.5 Circle of Fifths! 42 4.0 Messiaen: The Mathematics of his Musical Language! 45 4.1 Modes of Limited Transposition! 51 4.2 Non-retrogradable Rhythms! 58 5.0 Religious Symbolism and Mathematics in Music! 64 5.1 Numbers are God"s Tools! 65 5.2 Religious Symbolism and Numbers in Bach"s Music! 67 5.3 Messiaen"s Use of Mathematical Ideas to Convey Religious Ones! 73 6.0 Musical Mathematics: The Artistic Aspect of Mathematics! 76 6.1 Mathematics as Art! 78 6.2 Mathematical Periods! 81 6.3 Mathematics Periods vs. -

View Becomes New." Anton Webern to Arnold Schoenberg, November, 25, 1927

J & J LUBRANO MUSIC ANTIQUARIANS Catalogue 74 The Collection of Jacob Lateiner Part VI ARNOLD SCHOENBERG 1874-1951 ALBAN BERG 1885-1935 ANTON WEBERN 1883-1945 6 Waterford Way, Syosset NY 11791 USA Telephone 561-922-2192 [email protected] www.lubranomusic.com CONDITIONS OF SALE Please order by catalogue name (or number) and either item number and title or inventory number (found in parentheses preceding each item’s price). To avoid disappointment, we suggest either an e-mail or telephone call to reserve items of special interest. Orders may also be placed through our secure website by entering the inventory numbers of desired items in the SEARCH box at the upper left of our homepage. Libraries may receive deferred billing upon request. Prices in this catalogue are net. Postage and insurance are additional. An 8.625% sales tax will be added to the invoices of New York State residents. International customers are asked to kindly remit in U.S. funds (drawn on a U.S. bank), by international money order, by electronic funds transfer (EFT) or automated clearing house (ACH) payment, inclusive of all bank charges. If remitting by EFT, please send payment to: TD Bank, N.A., Wilmington, DE ABA 0311-0126-6, SWIFT NRTHUS33, Account 4282381923 If remitting by ACH, please send payment to: TD Bank, 6340 Northern Boulevard, East Norwich, NY 11732 USA ABA 026013673, Account 4282381923 All items remain the property of J & J Lubrano Music Antiquarians LLC until paid for in full. Fine Items & Collections Purchased Please visit our website at www.lubranomusic.com where you will find full descriptions and illustrations of all items Members Antiquarians Booksellers’ Association of America International League of Antiquarian Booksellers Professional Autograph Dealers’ Association Music Library Association American Musicological Society Society of Dance History Scholars &c. -

FRENCH SYMPHONIES from the Nineteenth Century to the Present

FRENCH SYMPHONIES From the Nineteenth Century To The Present A Discography Of CDs And LPs Prepared by Michael Herman NICOLAS BACRI (b. 1961) Born in Paris. He began piano lessons at the age of seven and continued with the study of harmony, counterpoint, analysis and composition as a teenager with Françoise Gangloff-Levéchin, Christian Manen and Louis Saguer. He then entered the Paris Conservatory where he studied with a number of composers including Claude Ballif, Marius Constant, Serge Nigg, and Michel Philippot. He attended the French Academy in Rome and after returning to Paris, he worked as head of chamber music for Radio France. He has since concentrated on composing. He has composed orchestral, chamber, instrumental, vocal and choral works. His unrecorded Symphonies are: Nos. 1, Op. 11 (1983-4), 2, Op. 22 (1986-8), 3, Op. 33 "Sinfonia da Requiem" (1988-94) and 5 , Op. 55 "Concerto for Orchestra" (1996-7).There is also a Sinfonietta for String Orchestra, Op. 72 (2001) and a Sinfonia Concertante for Orchestra, Op. 83a (1995-96/rév.2006) . Symphony No. 4, Op. 49 "Symphonie Classique - Sturm und Drang" (1995-6) Jean-Jacques Kantorow/Tapiola Sinfonietta ( + Flute Concerto, Concerto Amoroso, Concerto Nostalgico and Nocturne for Cello and Strings) BIS CD-1579 (2009) Symphony No. 6, Op. 60 (1998) Leonard Slatkin/Orchestre National de France ( + Henderson: Einstein's Violin, El Khoury: Les Fleuves Engloutis, Maskats: Tango, Plate: You Must Finish Your Journey Alone, and Theofanidis: Rainbow Body) GRAMOPHONE MASTE (2003) (issued by Gramophone Magazine) CLAUDE BALLIF (1924-2004) Born in Paris. His musical training began at the Bordeaux Conservatory but he went on to the Paris Conservatory where he was taught by Tony Aubin, Noël Gallon and Olivier Messiaen. -

Killer UX Design Preface

Killer UX Design About Jodie Moule Jodie Moule is co-founder and director of Symplicit, an experience design consultancy based in Australia that focuses on research, strategy, and design services. With a background in psychology, her understanding of human behavior is central to helping businesses see their brands through the eyes of customers, influencing the way they approach the design of their products, systems, and processes. About SitePoint SitePoint specializes in publishing practical, rewarding, and approachable content for web professionals. Visit http://www.sitepoint.com/ to access our books, blogs, newsletters, videos, and community forums. Preface When I embarked on my career as a psychologist, I never imagined I’d end up designing technology products and services. Funny where you end up in life, and lucky for me all those years at university weren’t wasted: the business of understanding humans and the way they behave is critical to designing. With the digital and physical worlds merging more than ever before, it is vital to understand how technology can enhance the human experience, and not cause frustration or angst at every touchpoint. To create technology that seamlessly fits into our daily lives, there’s a simple formula. First, consider the person attached to your technology solution and the context in which they’ll be using your creation; then, design your solution and involve users in the process to refine your thinking. Today, technology is used to change attitudes and behavior, creating amazing challenges for designers. And if we want to create products and services that have the power to educate people so that they may live better lives, or help to reduce the time people take to do certain tasks—or even attract them to our products instead of our competitors—we need to first understand what makes them tick. -

Leo Kraft's Three Fantasies for Flute and Piano: a Performer's Analysis

CHERNOV, KONSTANTZA, D.M.A. Leo Kraft's Three Fantasies for Flute and Piano: A Performer's Analysis. (2010) Directed by Dr. James Douglass. 111 pp. The Doctoral Performance and Research submitted by Konstantza Chernov, under the direction of Dr. James Douglass at The University of North Carolina at Greensboro (UNCG), in fulfillment of the requirements for the degree Doctor of Musical Arts, consists of the following: I. Chamber Recital, Sunday, April 27, 2008, UNCG: Trio for Piano, Clarinet and Violoncello in Bb Major, op. 11 (Ludwig van Beethoven) Sonatine for Flute and Piano (Henri Dutilleux) Sonata for Violin and Piano in A Major (César Franck) II. Chamber Recital, Monday, November 17, 2008, UNCG: Sonata for Violin and Piano in g minor (Claude Debussy) El Poema de una Sanluqueña, op. 28 (Joaquin Turina) Sonata for Violin and Piano in A Major, op. 13 (Gabriel Fauré) III. Chamber Recital, Tuesday, April 27, 2010, UNCG: Sonata for Two Pianos in D Major, K. 448 (Wolfgang Amadeus Mozart) The Planets, op. 32: Uranus, The Magician (Gustav Holst) The Planets, op. 32: Neptune, The Mystic (Gustav Holst) Fantasie-tableaux (Suite #1), op. 5 (Sergei Rachmaninoff) IV. Lecture-Recital, Thursday, October 28, 2010, UNCG: Fantasy for Flute and Piano (Leo Kraft) Second Fantasy for Flute and Piano (Leo Kraft) Third Fantasy for Flute and Piano (Leo Kraft) V. Document: Leo Kraft's Three Fantasies for Flute and Piano: A Performer's Analysis. (2010) 111 pp. This document is a performer's analysis of Leo Kraft's Fantasy for Flute and Piano (1963), Second Fantasy for Flute and Piano (1997), and Third Fantasy for Flute and Piano (2007). -

Composing Freedom: Elliott Carter's 'Self-Reinvention' and the Early

Composing Freedom: Elliott Carter’s ‘Self-Reinvention’ and the Early Cold War Daniel Guberman A dissertation submitted to the faculty of the University of North Carolina at Chapel Hill in partial fulfillment of the requirements for the degree of Doctor of Philosophy in the Department of Music. Chapel Hill 2012 Approved By, Brigid Cohen, chair Allen Anderson Annegret Fauser Mark Katz Severine Neff © 2012 Daniel Guberman ALL RIGHTS RESERVED ii ABSTRACT DANIEL GUBERMAN: Composing Freedom: Elliott Carter’s ‘Self-Reinvention’ and the Early Cold War (Under the direction of Brigid Cohen) In this dissertation I examine Elliott Carter’s development from the end of the Second World War through the 1960s arguing that he carefully constructed his postwar compositional identity for Cold War audiences on both sides of the Atlantic. The majority of studies of Carter’s music have focused on technical aspects of his methods, or roots of his thoughts in earlier philosophies. Making use of published writings, correspondence, recordings of lectures, compositional sketches, and a drafts of writings, this is one of the first studies to examine Carter’s music from the perspective of the contemporary cultural and political environment. In this Cold War environment Carter emerged as one of the most prominent composers in the United States and Europe. I argue that Carter’s success lay in part due to his extraordinary acumen for developing a public persona. And his presentation of his works resonated with the times, appealing simultaneously to concert audiences, government and private foundation agents, and music professionals including impresarios, performers and other composers.