Program Booklet

Total Page:16

File Type:pdf, Size:1020Kb

Load more

Recommended publications

-

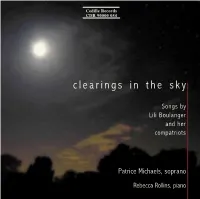

Clearings in the Sky

Cedille Records CDR 90000 054 c l e a r i n g s i n t h e s k y Songs by Lili Boulanger and her compatriots Patrice Michaels, soprano Rebecca Rollins, piano DDD Absolutely Digital™ CDR 90000 054 clearings in the sky GABRIEL FAURÉ (1845-1924) bm IV. Un poète disait . (1:44) 1 Vocalise-étude . (3:14) bn V. Au pied de mon lit . (2:23) 2 Tristesse . (2:51) bo VI. Si tout ceci n’est qu’un pauvre rêve . (2:28) 3 En prière . (2:46) bp VII. Nous nous aimerons tant . (2:49) LILI BOULANGER (1893-1918) bq VIII. Vous m’avez regardé avec toute votre âme . (1:32) 4 Reflets . (3:02) br IX. Les lilas qui avaient fleuri . (2:36) 5 Attente . (2:21) bs X. Deux ancolies . (1:20) 6 Le retour . (5:35) bt XI. Par ce que j’ai souffert . (3:01) MAURICE RAVEL (1875-1937) ck XII. Je garde une médaille d’elle . (1:59) 7 Pièce en forme de Habañera . (3:46) cl XIII. Demain fera un an . (8:42) CLAUDE DEBUSSY (1862-1918) OLIVIER MESSIAEN (1908-1992) 8 Le jet d’eau . (6:05) cm Le sourire . (1:35) LILI BOULANGER: Clairières dans le ciel (36:25) ARTHUR HONEGGER (1892-1955) 9 I. Elle était descendue au bas de la prairie . (2:00) cn Vocalise-étude . (2:11) bk II. Elle est gravement gaie . (1:47) LILI BOULANGER bl III. Parfois, je suis triste . (3:37) co Dans l’immense tristesse . (5:51) Patrice Michaels, soprano Rebecca Rollins, piano TT: (76:35) ./ Cedille Records is a trademark of The Chicago Classical Recording Foundation, a not-for-profit foundation devoted to promoting the finest musicians and ensembles in the Chicago area. -

Li-Li Boo-Lan-Jeh

Lili Boulanger Li-li Boo-lan-jeh (j is a soft g sound as in genre) Born: August 21st, 1893, Paris, France Died: March 15th, 1918, Mézy-sur-Seine, France “To study music, we must learn the rules. To create music, we must Period of Music: 20th Century, Modern break them.” – Nadia Boulanger, Lili’s beloved sister and teacher Biography: Lili Boulanger was born in 1893 in Paris, France to a musical family. Her mother, father, and sister Nadia were all trained composers or performers. When her father, Ernest, was only 20, he won the Prix de Rome. This coveted prize, which provided a year’s study in Rome, was the greatest recognition a young French composer could attain. Other winners of this prestigious award include Hector Berlioz, Gabriel Fauré, and Claude Debussy. Ernest Boulanger was 62 when he married a Russian princess. He was 72 years old when Nadia was born and 79 when Lili was born. He died when both children were still young. Lili’s immense talent was recognized early on, and at the age of 2 she began receiving musical training from her mom and eventually her older sister. In 1895 she contracted bronchial pneumonia, after which she was constantly ill. Because of her frail health, she relied entirely on private study since she was too weak to obtain a full music education at the Conservatoire. In 1913, Lili became the first woman to win the Prix de Rome for her Cantata Faust et Helene at the age of 20, the same age her father was when he won this award. -

La Voix Humaine: a Technology Time Warp

University of Kentucky UKnowledge Theses and Dissertations--Music Music 2016 La Voix humaine: A Technology Time Warp Whitney Myers University of Kentucky, [email protected] Digital Object Identifier: http://dx.doi.org/10.13023/ETD.2016.332 Right click to open a feedback form in a new tab to let us know how this document benefits ou.y Recommended Citation Myers, Whitney, "La Voix humaine: A Technology Time Warp" (2016). Theses and Dissertations--Music. 70. https://uknowledge.uky.edu/music_etds/70 This Doctoral Dissertation is brought to you for free and open access by the Music at UKnowledge. It has been accepted for inclusion in Theses and Dissertations--Music by an authorized administrator of UKnowledge. For more information, please contact [email protected]. STUDENT AGREEMENT: I represent that my thesis or dissertation and abstract are my original work. Proper attribution has been given to all outside sources. I understand that I am solely responsible for obtaining any needed copyright permissions. I have obtained needed written permission statement(s) from the owner(s) of each third-party copyrighted matter to be included in my work, allowing electronic distribution (if such use is not permitted by the fair use doctrine) which will be submitted to UKnowledge as Additional File. I hereby grant to The University of Kentucky and its agents the irrevocable, non-exclusive, and royalty-free license to archive and make accessible my work in whole or in part in all forms of media, now or hereafter known. I agree that the document mentioned above may be made available immediately for worldwide access unless an embargo applies. -

Francis Poulenc and Surrealism

Wright State University CORE Scholar Master of Humanities Capstone Projects Master of Humanities Program 1-2-2019 Francis Poulenc and Surrealism Ginger Minneman Wright State University - Main Campus Follow this and additional works at: https://corescholar.libraries.wright.edu/humanities Part of the Arts and Humanities Commons Repository Citation Minneman, G. (2019) Francis Poulenc and Surrealism. Wright State University, Dayton, Ohio. This Thesis is brought to you for free and open access by the Master of Humanities Program at CORE Scholar. It has been accepted for inclusion in Master of Humanities Capstone Projects by an authorized administrator of CORE Scholar. For more information, please contact [email protected]. Minneman 1 Ginger Minneman Final Project Essay MA in Humanities candidate Francis Poulenc and Surrealism I. Introduction While it is true that surrealism was first and foremost a literary movement with strong ties to the world of art, and not usually applied to musicians, I believe the composer Francis Poulenc was so strongly influenced by this movement, that he could be considered a surrealist, in the same way that Debussy is regarded as an impressionist and Schönberg an expressionist; especially given that the artistic movement in the other two cases is a loose fit at best and does not apply to the entirety of their output. In this essay, which served as the basis for my lecture recital, I will examine some of the basic ideals of surrealism and show how Francis Poulenc embodies and embraces surrealist ideals in his persona, his music, his choice of texts and his compositional methods, or lack thereof. -

Heitor Villa-Lobos and the Parisian Art Scene: How to Become a Brazilian Musician*

1 Mana vol.1 no.se Rio de Janeiro Oct. 2006 Heitor Villa-Lobos and the Parisian art scene: how to become a Brazilian musician* Paulo Renato Guérios Master’s in Social Anthropology at PPGAS/Museu Nacional/UFRJ, currently a doctoral student at the same institution ABSTRACT This article discusses how the flux of cultural productions between centre and periphery works, taking as an example the field of music production in France and Brazil in the 1920s. The life trajectories of Jean Cocteau, French poet and painter, and Heitor Villa-Lobos, a Brazilian composer, are taken as the main reference points for the discussion. The article concludes that social actors from the periphery tend themselves to accept the opinions and judgements of the social actors from the centre, taking for granted their definitions concerning the criteria that validate their productions. Key words: Heitor Villa-Lobos, Brazilian Music, National Culture, Cultural Flows In July 1923, the Brazilian composer Heitor Villa-Lobos arrived in Paris as a complete unknown. Some five years had passed since his first large-scale concert in Brazil; Villa-Lobos journeyed to Europe with the intention of publicizing his musical output. His entry into the Parisian art world took place through the group of Brazilian modernist painters and writers he had encountered in 1922, immediately before the Modern Art Week in São Paulo. Following his arrival, the composer was invited to a lunch in the studio of the painter Tarsila do Amaral where he met up with, among others, the poet Sérgio Milliet, the pianist João de Souza Lima, the writer Oswald de Andrade and, among the Parisians, the poet Blaise Cendrars, the musician Erik Satie and the poet and painter Jean Cocteau. -

Nationalism, Primitivism, & Neoclassicism

Nationalism, Primitivism, & Neoclassicism" Igor Stravinsky (1882-1971)! Biographical sketch:! §" Born in St. Petersburg, Russia.! §" Studied composition with “Mighty Russian Five” composer Nicolai Rimsky-Korsakov.! §" Emigrated to Switzerland (1910) and France (1920) before settling in the United States during WW II (1939). ! §" Along with Arnold Schönberg, generally considered the most important composer of the first half or the 20th century.! §" Works generally divided into three style periods:! •" “Russian” Period (c.1907-1918), including “primitivist” works! •" Neoclassical Period (c.1922-1952)! •" Serialist Period (c.1952-1971)! §" Died in New York City in 1971.! Pablo Picasso: Portrait of Igor Stravinsky (1920)! Ballets Russes" History:! §" Founded in 1909 by impresario Serge Diaghilev.! §" The original company was active until Diaghilev’s death in 1929.! §" In addition to choreographing works by established composers (Tschaikowsky, Rimsky- Korsakov, Borodin, Schumann), commissioned important new works by Debussy, Satie, Ravel, Prokofiev, Poulenc, and Stravinsky.! §" Stravinsky composed three of his most famous and important works for the Ballets Russes: L’Oiseau de Feu (Firebird, 1910), Petrouchka (1911), and Le Sacre du Printemps (The Rite of Spring, 1913).! §" Flamboyant dancer/choreographer Vaclav Nijinsky was an important collaborator during the early years of the troupe.! ! Serge Diaghilev (1872-1929) ! Ballets Russes" Serge Diaghilev and Igor Stravinsky.! Stravinsky with Vaclav Nijinsky as Petrouchka (Paris, 1911).! Ballets -

A Level Schools Concert November 2014

A level Schools Concert November 2014 An Exploration of Neoclassicism Teachers’ Resource Pack Autumn 2014 2 London Philharmonic Orchestra A level Resources Unauthorised copying of any part of this teachers’ pack is strictly prohibited The copyright of the project pack text is held by: Rachel Leach © 2014 London Philharmonic Orchestra ©2014 Any other copyrights are held by their respective owners. This pack was produced by: London Philharmonic Orchestra Education and Community Department 89 Albert Embankment London SE1 7TP Rachel Leach is a composer, workshop leader and presenter, who has composed and worked for many of the UK’s orchestras and opera companies, including the London Sinfonietta, the Orchestra of the Age of Enlightenment, Wigmore Hall, Glyndebourne Opera, English National Opera, Opera North, and the London Symphony Orchestra. She studied at the Guildhall School of Music and Drama, at Opera Lab and Dartington. Recent commissions include ‘Dope Under Thorncombe’ for Trilith Films and ‘In the belly of a horse’, a children’s opera for English Touring Opera. Rachel’s music has been recorded by NMC and published by Faber. Her community opera ‘One Day, Two Dawns’ written for ETO recently won the RPS award for best education project 2009. As well as creative music-making and composition in the classroom, Rachel is proud to be the lead tutor on the LSO's teacher training scheme for over 8 years she has helped to train 100 teachers across East London. Rachel also works with Turtle Key Arts and ETO writing song cycles with people with dementia and Alzheimer's, an initiative which also trains students from the RCM, and alongside all this, she is increasingly in demand as a concert presenter. -

Lili Boulanger (1893–1918) and World War I France: Mobilizing Motherhood and the Good Suffering

Lili Boulanger (1893–1918) and World War I France: Mobilizing Motherhood and the Good Suffering By Anya B. Holland-Barry A dissertation submitted in partial fulfillment of the requirements for the degree of Doctor of Philosophy (Music) at the UNIVERSITY OF WISCONSIN-MADISON 2012 Date of final oral examination: 08/24/2012 This dissertation is approved by the following members of the Final Oral Committee: Susan C. Cook, Professor, Music Charles Dill, Professor, Music Lawrence Earp, Professor, Music Nan Enstad, Professor, History Pamela Potter, Professor, Music i Dedication This dissertation is dedicated to my best creations—my son, Owen Frederick and my unborn daughter, Clara Grace. I hope this dissertation and my musicological career inspires them to always pursue their education and maintain a love for music. ii Acknowledgements This dissertation grew out of a seminar I took with Susan C. Cook during my first semester at the University of Wisconsin. Her enthusiasm for music written during the First World War and her passion for research on gender and music were contagious and inspired me to continue in a similar direction. I thank my dissertation advisor, Susan C. Cook, for her endless inspiration, encouragement, editing, patience, and humor throughout my graduate career and the dissertation process. In addition, I thank my dissertation committee—Charles Dill, Lawrence Earp, Nan Enstad, and Pamela Potter—for their guidance, editing, and conversations that also helped produce this dissertation over the years. My undergraduate advisor, Susan Pickett, originally inspired me to pursue research on women composers and if it were not for her, I would not have continued on to my PhD in musicology. -

Jessica Rivera, Soprano Kelley O'connor, Mezzo-Soprano Robert

CAL PERFORMANCES PRESENTS PROGRAM Sunday, October 13, 2013, 3pm Felix Mendelssohn (1809–1847) Volkslied (O säh ich auf der Heide dort), Hertz Hall Op. 63, No. 5 (1842) Ms. O’Connor & Ms. Rivera Jessica Rivera, soprano Mendelssohn Ich wollt, meine Lieb’ ergösse sich, Kelley O’Connor, mezzo-soprano Op. 63, No. 1 (1836) Robert Spano, piano Ms. O’Connor & Ms. Rivera Claude Debussy (1862–1918) Chansons de Bilitis (1897) PROGRAM I. La Flûte de Pan II. La Chevelure III. Le Tombeau des Naïades Camille Saint-Saëns (1835–1921) El Desdichado (1849) Ms. O’Connor Ms. O’Connor & Ms. Rivera Jonathan Leshnoff (b. 1973) Monica Songs (2012) David Bruce (b. 1970) That Time with You (2013) I. For Where Thou Go, I Will Go I. The Sunset Lawn II. We Cover Thee—Sweet Face II. That Time with You III. I thank You III. Black Dress IV. Greetings from Troy, Illinois IV. Bring Me Again V. So Much Joy World Premiere VI. There’s a Son Born to Naomi Ms. O’Connor World Premiere Ms. Rivera Federico Mompou (1893–1987) Combat del Somni (1942–1948) Gabriela Lena Frank (b. 1972) Selections from The Kitchen Songbook(2013) I. Damunt de tu només les flors II. Aquesta nit un mateix vent I. Honey III. Jo et pressentia com la mar Bay Area Premiere IV. Fes me la vida transparent II. Sofrito Ms. Rivera World Premiere Ms. O’Connor & Ms. Rivera Charles Gounod (1818–1893) La Siesta (1870) Ms. O’Connor & Ms. Rivera Funded by the Koret Foundation, this performance is part of Cal Performances’ 2013–2014 Koret Recital Series, which brings world-class artists to our community. -

School of Music Program Notes

First Half Deanna Buringrud,flute Gail Novak,piano Honors Project Recital Hall I April 7, 2019 j 12 p.m. Program Sonata for Flute and Piano Francis Poulenc Allegro malinconico Cantilena Presto giocoso First Sonata, for Flute and Piano Bohuslav Martinu I II III INTERMISSION ARIZONA STATE UNIVERSITY School of Music Program Notes First Sonata for Flute and Piano, Bohuslav Marinu (Dec. 1890 - 1959) Bohuslav Marinu was a Czech composer of early-mid 20th century. Bohuslav grew up in a family without material wealth. He began violin at a young age and excelled quickly. The town was impressed by his talent when attending his recitals, and raised the funds to send him to the Prague Conservatory in 1906. Martinu was expelled from the Prague conservatory in 1910 due to "incorrigible negligence." Martinu became more interested in the composition aspect of music than his individual performance, and as such did not practice his violin enough. First Sonata for Flute and Piano was composed in 1945 in South Orleans, Cape Cod. During this time, Marinu was living in the United States to escape France when it was occupied by the Nazis in WW2. Though he didn't speak english very well, Martinu quickly adapted to his environment and ended up teaching both at Princeton and the Tanglewood institution in Berkshire. First Sonata was written for Georges Laurent, the principle flutist of the Boston Symphony. It premiered in New York 1949. Remnants ofMartinu's past can be heard throughout the sonata, such as the perfect fourths in the first movement that represent the church bells his father rang. -

The Rite of Spring

The Rite of Spring This weekend we’re afforded the opportunity to experience two seldom-heard works: Dvořák’s piano concerto and Lili Boulanger’s dark-night-of-the-soul set to music, D’un soir triste. Stravinsky’s The Rite of Spring — a watershed in the history of Western classical music — comprises the second half. ILI BOULANGER Born 21 August 1893; Paris, France Died 15 March 1918; Mézy-sur-Seine, France D’un soir triste Composed: 1918 First performance: 6 March 1921; Paris, France (chamber work), 9 May 1992; San Francisco, California (orchestral work) Last MSO performance: MSO premiere Instrumentation: 2 flutes, 2 oboes, English horn, 2 clarinets, bass clarinet, 2 bassoons, contrabassoon, 4 horns, 3 trumpets, 3 trombones, tuba, timpani, percussion (bass drum, suspended cymbals, tam tam), harp, celeste, strings Approximate duration: 9 minutes Lili Boulanger was the younger sister of the noted teacher, conductor, and composer Nadia Boulanger (1887-1979). As a child, she accompanied Nadia to classes at the Paris Conserva- toire. She later studied organ with Louis Vierne. Lili also sang and played piano, violin, cel- lo, and harp. The first woman to receive the Prix de Rome — in 1913, for her cantata Faust et Hélène — her composing life was brief but productive. Her most important works are her psalm settings and other large-scale choral pieces. Fauré admired and promoted her music. D’un soir triste (On a Sad Evening) was written in the final months of her life (often beset by illness, she died at the early age of 24), along with a shorter companion piece, D’un matin de printemps (On a Morning in Spring). -

Lili Bio-Formatted

Lili with fellow Prix de Rome finalists, 1913 Lili Boulanger: An Iron Flower Lili Boulanger was exceptionally talented, born into musical (and perhaps Russian) aristocracy in 1893. Her father Ernest, an opera composer, professor at the Paris Conservatory, and past winner of the prestigious Prix de Rome for composition, was the scion of generations of musicians; her mother, Raïssa Mychetsky, was a purported Russian princess. Sister Nadia, six years her senior, would become a leading light of the Paris Conservatory and the most influential music pedagogue of the 20th century. Fauré, Ravel, Widor, and other luminaries of the French musical world were family friends and mentors. It was Fauré who discovered that 2-year-old Lili had perfect pitch. Tragically, all of Lili’s brilliance and education were ultimately at the mercy of her body. After a childhood bout of bronchial pneumonia weakened her immune system, she suffered from poor health and often debilitating illness throughout her life. Lili was determined from age 16 to win the Prix de Rome. Nadia had tried and failed to win four times, held back largely by politics. Her compositions were considered by her teachers Charles Widor and Raoul Pugno to be the best of the field, but she was a woman. Lili studied intensely and first undertook the grinding competition in 1912, but was forced to drop out due to illness. She made another attempt the following year, deploying her own political stratagems (she solicited letters of support from teachers and mentors), and even used her own physical fragility as a tool. As Anna Beer notes in her chapter on Boulanger (Beer, Anna.