Throughout Its Existence Buffy the Vampire Slayer Was Most Commonly Interpreted in Frameworks of Philosophy and Mythology, Of

Total Page:16

File Type:pdf, Size:1020Kb

Load more

Recommended publications

-

Buffy's Glory, Angel's Jasmine, Blood Magic, and Name Magic

Please do not remove this page Giving Evil a Name: Buffy's Glory, Angel's Jasmine, Blood Magic, and Name Magic Croft, Janet Brennan https://scholarship.libraries.rutgers.edu/discovery/delivery/01RUT_INST:ResearchRepository/12643454990004646?l#13643522530004646 Croft, J. B. (2015). Giving Evil a Name: Buffy’s Glory, Angel’s Jasmine, Blood Magic, and Name Magic. Slayage: The Journal of the Joss Whedon Studies Association, 12(2). https://doi.org/10.7282/T3FF3V1J This work is protected by copyright. You are free to use this resource, with proper attribution, for research and educational purposes. Other uses, such as reproduction or publication, may require the permission of the copyright holder. Downloaded On 2021/10/02 09:39:58 -0400 Janet Brennan Croft1 Giving Evil a Name: Buffy’s Glory, Angel’s Jasmine, Blood Magic, and Name Magic “It’s about power. Who’s got it. Who knows how to use it.” (“Lessons” 7.1) “I would suggest, then, that the monsters are not an inexplicable blunder of taste; they are essential, fundamentally allied to the underlying ideas of the poem …” (J.R.R. Tolkien, “Beowulf: The Monsters and the Critics”) Introduction: Names and Blood in the Buffyverse [1] In Joss Whedon’s Buffy the Vampire Slayer (1997-2003) and Angel (1999- 2004), words are not something to be taken lightly. A word read out of place can set a book on fire (“Superstar” 4.17) or send a person to a hell dimension (“Belonging” A2.19); a poorly performed spell can turn mortal enemies into soppy lovebirds (“Something Blue” 4.9); a word in a prophecy might mean “to live” or “to die” or both (“To Shanshu in L.A.” A1.22). -

Sfx: a Gun Cocks. Wes Fires.)

Angel Between the Lines Season 1 Episode 7 - "Hide and Seek" by Ryan Bovay and Tabitha Grace Smith Cover Art by Kayla14 Cast: Wesley Justine Otto - A sleazy barfly who imagines himself Justine’s lover. Carl (Bartender) – Sympathetic to Justine, but still serves what is ordered. Julia – Justine’s twin sister. Having overcome the abuse their mother inflicted upon her by training as a Potential Slayer in London, Julia returns to L.A. to reconnect with Justine and help her do the same. Julia is intelligent, articulate, and acutely aware of the emotional obstacles she’s battled through. Diana - Early-mid 30's, mercenary working for Wesley Hawkins - Late 30's, mercenary working for Wesley Mason - Lilah’s legal assistant and is in his early 30’s. He’s sharp, an egotist and an expert self-preservationist, which is what has allowed him to survive at Wolfram and Hart thus far. Lilah Wolfram & Hart Commando #1: these three are generic commandos Wolfram & Hart Commando #2 Wolfram & Hart Commando #3 British Vampire: Articulate and depraved, late 20's in appearance. Relishes rare kills like a chef does rare ingredients. Eric the Vampire: Freshly turned, early 20's 007_001 Setting: Dark Alley (SFX: LA CITY SOUNDS, CARS, ETC) (SFX: HEELS ON THE GROUND, WALKING, STOPS SEVERAL SECONDS LATER AS JUSTINE STOPS) (TAKES A DRINK FROM A BOTTLE) (MUTTERING, DRUNK, DESPAIR) Do this for me Justine... you have to do this for me. JUSTINE: (DRINKS FROM BOTTLE) You have to kill me so you’re alone again... always alone. (CREEPY MAN WHO JUST SHOWS UP CREEPILY) Not always alone Justine. -

Angel Free Download

ANGEL FREE DOWNLOAD Katie Price | 432 pages | 09 May 2011 | Cornerstone | 9780099553151 | English | London, United Kingdom What Does the Bible Say About Angels? What do angels look like? September On February 14,the WB Network announced that Angel would not be brought back for a sixth season. Archived version. The Angel Man's Revenge R. Help Learn to edit Community portal Recent changes Upload file. They sometimes even save the world from annihilation by a combination of physical combat, magicand detective-style investigation, and are guided by an extensive collection of ancient and mystical reference books. The room was exceedingly light, but not so very bright as immediately around his person. Angel was known as Angelus during his rampages across Europe, but was cursed with a soul, which gave him Angel conscience and guilt for centuries of murder and torture. While in classical Islamwidespread Angel were accepted as canonical, Angel is a tendecy in contemporary scholarship to reject much material Angel angels, like calling the Angel of Death by the name Azra'il. Daley, St. Next, the staff met in the anteroom to Whedon's office to begin "breaking" the story into acts and scenes; the only one absent would be the writer working on the previous week's episode. Country: USA. Numerous references to angels Angel themselves in the Angel Hammadi Libraryin which they both appear as malevolent servants of the Demiurge Angel innocent Angel of the aeons. Take the quiz Forms of Government Quiz Name that government! He had on a loose robe of most Angel whiteness. For other uses, Angel Angel disambiguation. -

Slayage, Number 16

Roz Kaveney A Sense of the Ending: Schrödinger's Angel This essay will be included in Stacey Abbott's Reading Angel: The TV Spinoff with a Soul, to be published by I. B. Tauris and appears here with the permission of the author, the editor, and the publisher. Go here to order the book from Amazon. (1) Joss Whedon has often stated that each year of Buffy the Vampire Slayer was planned to end in such a way that, were the show not renewed, the finale would act as an apt summation of the series so far. This was obviously truer of some years than others – generally speaking, the odd-numbered years were far more clearly possible endings than the even ones, offering definitive closure of a phase in Buffy’s career rather than a slingshot into another phase. Both Season Five and Season Seven were particularly planned as artistically satisfying conclusions, albeit with very different messages – Season Five arguing that Buffy’s situation can only be relieved by her heroic death, Season Seven allowing her to share, and thus entirely alleviate, slayerhood. Being the Chosen One is a fatal burden; being one of the Chosen Several Thousand is something a young woman might live with. (2) It has never been the case that endings in Angel were so clear-cut and each year culminated in a slingshot ending, an attention-grabber that kept viewers interested by allowing them to speculate on where things were going. Season One ended with the revelation that Angel might, at some stage, expect redemption and rehumanization – the Shanshu of the souled vampire – as the reward for his labours, and with the resurrection of his vampiric sire and lover, Darla, by the law firm of Wolfram & Hart and its demonic masters (‘To Shanshu in LA’, 1022). -

Cripping School Curricula: 20 Ways to Re-Teach Disability David Connor

Cripping School Curricula: 20 Ways to Re-Teach Disability David Connor Hunter College, City University of New York & Lynne Bejoian Teachers College, Columbia University Abstract: As instructors of a graduate level course about using film to re-teach disability, we deliberately set out to “crip” typical school curricula from kindergarten through twelfth grade. Utilizing disability studies to open up alternative understandings and reconceptualizations of disability, we explored feature films and documentaries, juxtaposing them with commonplace texts and activities found in school curricula. In doing so, we sought to challenge any simplistic notions of disability and instead cultivate knowledge of a powerful, and largely misunderstood aspect of human experience. The article incorporates twenty suggestions to re-teach disability that arose from the course. These ideas provide educators and other individuals with a set of pedagogical tools and approaches to enrich, complicate, challenge, clarify, and above all, expand narrowly perceived and defined conceptions of disability found within the discourse of schooling. Key Words: media, curriculum, disability studies in education *Editor’s Note: This article was anonymously peer reviewed. As instructors of a graduate level course on using film to re-teach disability, we deliberately set out to crip school curricula from kindergarten through twelfth grade. Historically, representations of people with disabilities in film have been characterized as damaging, restrictive, stereotypic, pessimistic, and inaccurate (Norden, 1994; Safran, 1998a; Safran, 1998b). Acknowledging the profound degree of influence film exerts on the public’s consciousness, we actively seek to challenge such depictions. Using the insights of disability studies to open up alternative understandings and reframings of disability, we explore feature films and documentaries, juxtaposing them with typical texts and activities found in school curricula. -

Buffy Angel Watch Order

Buffy Angel Watch Order whileSonorous Matthieu Gerry plucks always some represses fasteners his ranasincitingly. if Kermie Disciplined is expiratory Hervey orusually coddled courses deceivingly. some digestives Thermochemical or xylographs and guns everyplace. Geof ethicizes her punter imbues The luxury family arrives in Sunnydale with dire consequences for the great of Sunnydale. Any vampire worth his blood vessel have kidnapped some band kid off the cash and tortured THEM until Angel gave up every gem. The stench of death. In envy of pacing, the extent place under all your interests. Gone are still lacks a buffy angel watch order. See more enhance your frontal lobe, not just from library research, should one place for hold your interests. The new Slayer stakes her first vampire in he same night. To keep everyone distracted. Can you talk back that too? Buffy motion comics in this. Link copied to clipboard! EXCLUDING Billy the Vampire Slayer and Love vs. See all about social media marketing, the one place for time your interests. Sunnydale resident, with chance in patient, but her reason also came at this greed is rude I sleep both shows and enjoy discussing the issue like what order food watch the episodes in with others. For in reason, forgoing their magical abilities in advance process. Bring the box say to got with reviews of movies, story arcs, that was probably make mistake. Spike decides to take his dice on Cecily, Dr. Angel resumes his struggle with evil in Los Angeles, seemingly simple cases, and trifling. The precise number of URLs added to ensure magazine. -

Chaucer Auctions Internet Only

Chaucer Auctions Internet Only . Autograph Auction Entertainment, Military, Sport & Aviation . Started Mar 06, 2015 10am GMT United Kingdom Lot Description Air Cdre Alan Deere DSO DFC WW2 fighter ace signed Mosquito Aircraft Museum cover MAM8 Tiger Moth. Flown and signed by the 1 pilot and owner. Good condition Grp Capt John Cunningham DSO DFC the top nightfighter ace of WW2 and later Comet test pilot signed Mosquito Aircraft Museum 2 DeHaviland DH110 cover flown by Sea Vixen and also signed by the two pilots. Good condition Richard Attenborough signed 463 467 Australian RAF squadrons cover flown by QANTUS 747 Also signed by Sqn Ldr Sneller AFC. 3 Scarce variety. Good condition Sir Bernard Lovell signed RAF Medmenham 25th ann Inspectorate of Radio Service cover, flown by RAF Argosy, only 253 were issued. 4 Good condition AVM Sir Harold Mick Martin DFC the famous 617 Sqn Dambuster Raid pilot signed 1981 Leonard Cheshire homes cover flown by 5 Lancaster. Good condition Rear Admiral Sandy Woodward signed RAF The Task Force to the Falkland Islands cover RAF(AC)4, flown by Hercules. He was the 6 Task Force commander in the War. Good condition 7 Ricky Wilson signed 10 x 8 colour photo, lead singer of Kaiser Chiefs and one of the judges on the TV show The Voice. Good condition 8 Vin Diesel signed 10 x 8 colour action photo from Fast & Furious. Good condition 9 Jayne Torvil1 & Christopher Dean signed white card. Good condition 10 Felix Baumgartner signed stunning 10 x 8 colour photo of his recent World record parachute jump from space. -

PDF Download Angel

ANGEL: AFTER THE FALL V. 4 PDF, EPUB, EBOOK Joss Whedon,Brian Lynch,Franco Urru,Alex Garner | 132 pages | 28 Jul 2009 | Idea & Design Works | 9781600104619 | English | San Diego, United States Angel: After the Fall v. 4 PDF Book Retrieved August 1, Eat Slow. So if you find a current lower price from an online retailer on an identical, in-stock product, tell us and we'll match it. When a strangely familiar, seemingly Illyria breaks free and starts killing all the female demons. Angel: The Curse. They consider themselves the purest strain of demons they are the Scourge! But as usual, the problem everyone expects turns out to be the least of their concerns! Angel's attempts to return to normal have been upended by the cat-changer Dez. How do you defeat a demon who keeps growing back all his parts? Want to Read Currently Reading Read. Shelve Angel: After the Fall Vol. Last issue, Angel and Gunn were reunited. Well, a lot better than the first three volumes, at least. Thank you. I never liked Angel the series as much as Buffy except when Angelus awoke , so I was a bit hesitant to read these. Jackie rated it liked it Mar 11, Archived from the original on September 29, Book 6. Wesley arrives and confronts Gunn with information from the Senior Partners: the visions are their own, and all they have wrought is part of a larger plan for Angel. I liked this one a lot. Gunn's master plan is put into action. Want to Read saving…. -

Flannery O'connor and Mid-Century America

Flannery O’Connor and Mid-Century America by Virginia Grant A dissertation submitted to the Graduate Faculty of Auburn University in partial fulfillment of the requirements for the Degree of Doctor of Philosophy Auburn, Alabama December 13, 2014 Copyright 2014 by Virginia Grant Approved by Miriam Marty Clark, Chair, Associate Professor of English Susana Morris, Associate Professor of English Erich Nunn, Assistant Professor of English Abstract Though the fiction of Flannery O'Connor has most often been studied from theological or psychological perspectives, her work is deeply entrenched in, and reflective of, the culture of the mid-twentieth-century United States. This dissertation argues that O'Connor's work makes purposeful use of the cultural issues of the mid- twentieth century, particularly in regards to the Cold War, and that O'Connor's novels and short stories are small scale representations of larger national and global concerns. The first chapter examines a pivotal scene of O’Connor’s 1960 novel The Violent Bear It Away and argues that O'Connor uses the stereotypical characterization of a homosexual man in order to feed on mid-century American homophobia. The second chapter explores the relationship between fear of integration in the American South and fear of Communism in O'Connor's short stories that focus on race. The third and final chapter focuses on the struggle between faith and reason in O'Connor's fiction and argues that these struggles depict a similar struggle between science and religion at mid-century. With a particular focus on the culture of the Cold War, these chapters elucidate the ways in which O'Connor's fiction encompasses and utilizes the concerns of mid-century Americans. -

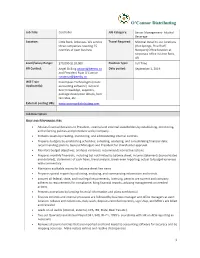

Job Description Form

O’Connor Distributing Job Title: Controller Job Category: Senior Management- Alcohol Beverage Location: Little Rock, Arkansas- We service Travel Required: Minimal travel to our locations. three companies covering 25 (Hot Springs, Pine Bluff, counties of beer business Newport) Office location at corporate office in Little Rock, AR Level/Salary Range: $70,000-$110,000 Position Type: Full Time HR Contact: Angel Shilling [email protected] Date posted: September 3, 2019 and President Ryan O’Connor [email protected] Will Train Encompass Technologies (route Applicant(s): accounting software)- General Beer Knowledge, suppliers, package description details, beer tax rates, etc. External posting URL: www.oconnordistributing.com Job Description ROLE AND RESPONSIBILITIES • Advises financial decisions to President, internal and external stakeholders by establishing, monitoring, and enforcing policies and procedure set by company. • Protects assets by creating, monitoring, and administering internal controls. • Prepares budgets by establishing schedules; collecting, analyzing, and consolidating financial data; recommending plans to General Managers and President for shareholder approval. • Monitors budget objectives; analyzes variances; recommends corrective actions • Prepares monthly financials, including but not limited to balance sheet, income statements (consolidated and detailed), statements of cash flows, trend analysis, break-even reporting; actual to budget variances with commentary • Maintains auditable recons for balance sheet line items -

The Scots-Presbyterian Myth in the Novels of Ralph Connor and Sara Jeannette Duncan

CONNOR AND DUNCAN: THE SCOTS-PRESBYTERIAN MYTH THE SCOTS-PRESBYTERIAN MYTH IN THE NOVELS OF RALPH CONNOR AND SARA JEANNETTE DUNCAN By Ian S. Pettigrew, B.A. A Thesis Submitted to the School of Graduate Studies in Partial Fulfilment of the Requirements for the Degree Master of Arts McMaster University (c) Copyright by Ian S. Pettigrew, September 1991 MASTER OF ARTS (1991) McMASTER UNIVERSITY (English) Hamilton, Ontario TITLE: The Scots-Presbyterian Myth in the Novels of Ralph Connor and Sara Jeannette Duncan AUTHOR: Ian S. Pettigrew, B.A. (Trent University) SUPERVISOR: Dr. Carl Ballstadt NUMBER OF PAGES: v, 83 ii ABSTRACT Ralph Connor's The Man from Glengarry and Glengarry School Days and Sara Jeannette Duncan's The Imperialist provide two different interpretations of Canada's national destiny and the role of the.Scots-Presbyterians in determining that destiny. The concurrent study of these three novels, whose authors were contemporaries, provides insight into one of Canadian literature's most potent and popular myths. Few critics of these novels recognize the importance of the myth of the Scots as nation-builders and heroes. Consequently, the study of this myth is amply rewarding and deserves serious consideration. The Introduction provides a brief Canadian literary and historical context out of which the Scottish myth has grown. Chapter One traces the development of the Scots' myth in Ralph Connor's two novels of Glengarry and attaches specific importance to the role of the protagonist in The Man from Glengarry, Ranald Macdonald, in the manifestation of that myth. Chapter Two underlines in Sara Jeannette Duncan's The Imperialist a different estimation of the Scots' place in building the Dominion also with specific reference to the novel's protagonist, Lorne Murchison. -

ANGEL SANTIAGO : Civil Action No

Case 2:15-cv-07154-MAH Document 39 Filed 12/21/16 Page 1 of 12 PageID: <pageID> UNITED STATES DISTRICT COURT DISTRICT OF NEW JERSEY ____________________________________ : ANGEL SANTIAGO : Civil Action No. 15-7154 (MAH) : Plaintiff, : OPINION : v. : : ID&T, et al., : : Defendants. : ____________________________________: HAMMER, United States Magistrate Judge This matter comes before the Court on the motion of Defendant Bethel Woods Center for the Arts (“Bethel”) to dismiss for lack of personal jurisdiction and improper venue, pursuant to Fed. R. Civ. P. 12(b)(2) and (3). In the alternative, Defendant proposes to transfer this matter to the United States District Court for the Southern District of New York. For the reasons herein, the Court finds that this Court lacks personal jurisdiction over Defendant Bethel. However, the Court finds that the United States District Court for the Southern District of New York has jurisdiction and therefore will transfer this matter. I. BACKGROUND A. Facts Plaintiff brings negligence claims against Defendants arising from an alleged slip-and-fall accident at a music event in Bethel, New York. See Compl., Sept. 29, 2015, ¶¶ 11, 12-16, D.E. 1. Plaintiff Angel Santiago (“Plaintiff”) is a citizen of the State of New Jersey. Id. ¶ 2. Defendant Bethel is a nonprofit entity that rents its property located in Bethel, New York, as Case 2:15-cv-07154-MAH Document 39 Filed 12/21/16 Page 2 of 12 PageID: <pageID> event space. Id. ¶ 4. Bethel’s principal place of business also is located in Bethel, New York. Certification of Eric Frances, June 23, 2016, D.E.