ASMMR Newsletter Vol 1 Issue 6

Total Page:16

File Type:pdf, Size:1020Kb

Load more

Recommended publications

-

Pukekohe Toyota

Traffic lights in Franklin County Pukekohe 3 Bridge club dresses to impress 4 NEWSTuesday, November 8, 2016 Pukekohe putsiton Pukekohe delivered a weekend of fast-car heaven as 106,753 supercar fans flocked to the spiritual home of New Zealand motorsport - Pukekohe Park - for the ITM Auckland Supersprint. It was an emotional finish to the three days of racing for Supercar championship leader, Kiwi Shane Van Gisbergen, (inset) as he claimed the Jason Richards Memorial Trophy, for recording the best results over the weekend’s event. Turn to P6-7 and P18-19 to check out all the action from the weekend. Photos: Daniel Kalisz, GETTY IMAGES SATURDAY 19 NOV 2016 The SsangYong Counties Cup returns to Pukekohe Park for 2016 showcasing thrilling horse racing, entertainment and hospitality. Featuring the Lone Star Pukekohe Fashion in the Field Book your tickets today www.PukekohePark.co.nz 2 FRANKLIN COUNTY NEWS, NOVEMBER 8, 2016 stuff.co.nz YOUR PAPER, YOUR PLACE 1. VALLEY SCHOOL GALA Valley School celebrates its 50th This newspaper is subject to NZ Press anniversary with a Golden Gala day Council procedures. FROM on November 12 from 10am-2pm. A complaint must first Face-painting, pony rides, quick-fire be directed in writing, THE raffles and more. within one month of EDITOR publication, to the editor’s email address. 2. COUNTIES CUP FASHION If not satisfied with the response, the complaint may be referred to the Pukekohe Lone Star Fashion in the Press Council. PO Box 10-879, Field will be held at SsangYong The Terrace, Wellington 6143. Counties Cup Day at Pukekohe Or use the online complaint form at There’s less than a month left to Park from 12pm on November 19. -

N Views from the Group | December 2016

NEWS ‘N VIEWS FROM THE GROUP | DECEMBER 2016 CHAIRMAN UPDATE I’m sure you’re all interested in how our branches coped during the recent earthquakes, and it’s pleasing to report there was only minor damage to our Blenheim and Lower Hutt stores. Fortunately the main initial shake was at night, so all our staff were safe and are coping well, and both branches have since undergone engineering assessments and are back trading. The Plumbing World team are now working hard with our suppliers and freight companies to ensure we have the minimum of disruption while the country deals with a very sad and battered Kaikoura region, and our thoughts go out to everyone who has been affected. On a more positive note, thank you to all those who joined our results update webinar on 24 November, and it was a great opportunity to further share the details of both the improved financial performance, and the progress the NZPM co-op has made in the first half of the financial year. Our forecast for the second half of the year remains positive, so it’s great to see the initiatives that we’ve been implementing over the last 12-18 months are bearing fruit. This was our first webinar with shareholders, so we’d be delighted to receive your feedback on this format of communication with members. As I’ve mentioned in recent Connector articles, both the board and our executive team want to know how best to communicate with you, so any suggestions you have will be appreciated. -

Scalextric Aussie V8 Supercars: the Holdens! (Page 1 of 2)

Scalextric Aussie V8 Supercars: The Holdens! (Page 1 of 2) 25 of the 46 Supercars. Produced by the A.S.R.C.C. for the enjoyment of Club members! www.scalextricaustralia.com 2002 Holden 2003 Holden 2004 Holden 2005 Holden C2446 Castrol Perkins Racing C2519 Garry Rogers Motorsport C2612 Castrol Perkins Racing C2692 Paul Weel Racing Russell Ingall #8 (9th Place) Garth Tander #34 (12th Place) Steven Richards #11 (5th Place) Greg Murphy #51 (11th Place) 2006 Holden 2006 Holden 2007 Holden 2007 Holden C2768 Paul Weel Racing C2769 Tasman Motorsport C2832 Holden Racing Team C2954 HSV Dealer Team Greg Murphy #51 (24th Place) Jason Richards #3 (18th Place) Mark Skaife #2 (8th Place) Garth Tander #16 (Champion) 2009 Holden 2008 Holden 2010 Holden 2010 Holden C3040 Tasman Motorsport C3041 Holden Racing Team C3114 Holden Racing Team C3115 Paul Morris Motorsport Greg Murphy #51 (21st Place) Garth Tander #1 (3rd Place) Will Davison #22 (22nd Place) Russell Ingall #39 (12th Place) For enquiries on this poster please This poster is possible contact Dominic Grimes, President, with thanks to Scalextric, A.S.R.C.C.: Southern Model Supplies [email protected] & A.S.R.C.C. sponsors: (Version 2 9/9/20) www.slotshop.com.au www.slotscarsalive.com ) Scalextric Aussie V8 Supercars: The Holdens! (Page 2 of 2) 25 of the 46 Supercars. Produced by the A.S.R.C.C. for the enjoyment of Club members! www.scalextricaustralia.com 2010 Holden 2011 Holden 2012 Holden 2013 Holden C3161 Triple Eight Race Engineering C3227 Holden Racing Team C3322 Triple Eight Race -

ASMMR Newsletter Vol 2 Issue 4

Volume 2, Issue 4 May 2010 The Australasian Society for Motorsports Medicine and Rescue Contents Race control Clinical review Recent race results Worldwide motorsport update Caught by the cameras Race control Welcome to the May edition of the ASMMR newsletter. The various racing categories are moving on a pace and there is plenty to talk about in the world of motorsport medicine and rescue. This issue takes a look at some track safety devices; namely the run-off areas and gravel traps – the pros, the cons and the downright scary. There is a review of recent race events and a few highlights from other aspects of motorsporting news. If you have ever wanted to know what a tank slapper, a lambda reading or reactive suspension was, then skip to the Wikipedia motorsports terminology link. Good luck. Matthew Mac Partlin Technical review Track safety devices – Run-offs and gravel traps Competitors and race vehicles can be fully prepared with safety equipment, but at some point or other a vehicle will unintentionally veer off the track. Sometimes the driver will be able to gather it up and rejoin the race, if there is sufficient space to do so. However, there is often a conflict between race track safety, spectator friendliness and geography. The safest track would probably be a straight road, with a wide run-off to either side and at either end and have no more Copyright Matthew Mac Partlin, 2010 Page 1 of 9 than a couple of cars competing on it at any one time. But it wouldn’t be terribly interesting to compete in or to watch. -

Simoncelli, Di Meglio and Dunlop Celebrate in Style!

THE OFFICIAL MAGAZINE OF DUNLOP MOTORSPORT IN TOUCH [ www.injection.tv ] ISSUE TEN, NOVEMBER 2008 Simoncelli, di Meglio and Dunlop celebrate in style! Marco Simoncelli and Alvaro Bautista have been the most consistent finishers in the MotoGP 250cc category, each scoring in 13 of the 15 races this year and are first and second in the riders' standings with one race remaining, in Valencia at the end of October. With his third place finish in Malaysia mid-October, seconds behind Bautista at the chequered flag, it was Simoncelli who was crowned the 2008 250cc champion and the Italian celebrated by completing a helmet-less victory lap around the track. Simoncelli has scored five wins to Bautista's four so far this year, but the Italian has consistently finished on the podium. Mid-season he was on devastating form, finishing second to Mika Kallio in France, and then winning the Spanish and German Grands Prix, finishing second in Britain, and third at the Dutch Grand Prix. Bautista had fallen far behind by the time the bikes lined up in Spain, having scored one win, but just 16 more points in the Mike di Meglio wins the Australian 125cc race and Dunlop's 12th straight category title opening six races. The Spaniard worked hard during the second half of the year, starting on his home ground where he was second to Simoncelli, and that led Dunlop celebrates another successful to a run of six straight podium finishes, culminating in victory in South Africa. The series was interrupted by Hurricane motorcycle racing season in 2008 Ike, which caused the cancellation of the Dunlop is celebrating another American 250cc Grand Prix, but in the Win number 50 came with performance.” next three races in Japan, Australia and fantastically successful season Valentino Rossi at the 1999 British “We thank the teams for putting Malaysia, Simoncelli again applied the in motor cycle racing. -

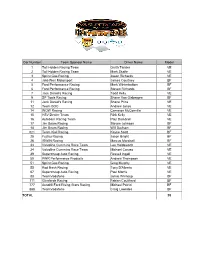

Radio Frequencies.Xls Amended As at 1/10/2010 2:08 PM

1ENTRY LIST FOR RACE 18 OF THE 2010 AUSTRALIAN V8 SUPERCAR CHAMPIONSHIP SERIES BEING HELD AT MOUNT PANORAMA, BATHURST 7 - 10 OCTOBER 2010 FIRST ISSUE Car # Team Sponsor Name Driver A Driver B Driver C Freq (MHz) 1 TeamVodafone Jamie Whincup Steve Owen Mark Skaife 469.5750 2 Toll Holden Racing Team Garth Tander Cameron McConville David Reynolds 450.4500 3 Centaur Racing Tony D'Alberto Shane Price 454.7000 4 IRWIN Racing Alex Davison David Brabham John McIntyre 469.6125 5 Orrcon Steel FPR Falcon Mark Winterbottom Luke Youlden James Moffat 463.4625 6 Dunlop Super Dealer FPR Falcon Steven Richards Luke Youlden James Moffat 464.4125 7 Jack Daniel's Racing Todd Kelly Dale Wood Owen Kelly 453.4375 8 Team BOC Jason Richards Andrew Jones Matt Halliday 453.0875 9 SP Tools Racing Shane van Gisbergen David Brabham John McIntyre 463.4750 10 Bundaberg Red Racing Team Andrew Thompson Ryan Briscoe Craig Baird 450.1500 11 Rock Racing Jason Bargwanna Glenn Seton Taz Douglas 456.7500 12 Bing Lee/Panasonic Racing Dean Fiore Michael Patrizi 466.4750 14 Trading Post Racing Jason Bright Andrew Jones Matt Halliday 456.9250 15 Jack Daniel's Racing Rick Kelly Dale Wood Owen Kelly 458.3125 16 Stratco Racing Tony Ricciardello Glenn Seton Taz Douglas 454.8250 17 Jim Beam Racing Steven Johnson Marcus Marshall Warren Luff 450.4000 18 Jim Beam Racing James Courtney Marcus Marshall Warren Luff 457.6750 19 Dick Johnson Racing Jonathon Webb David Russell 454.4000 21 Fair Dinkum Sheds Racing Karl Reindler David Wall 456.2125 22 Toll Holden Racing Team Will Davison Cameron -

Proudly Sponsored

P/P 328030/00114 - P/P 100005100 Proudly sponsored by: DISCLAIMER: Readers are reminded that opinions expressed in the CLUB PHONE: 03 87965321 Victorian Flagmarshalling News are not necessarily those of the Editor, CLUB MOBILE: 0409 823657 VFT or its oficers, that articles are published in good faith and that no responsibility will be accepted. Readers are also advised that certain parts of the magazine are protected by copyright. Please send articles and photos by the 24th of even months to: magazine@vicϐlag.org.au ABN 53 038 411 980 ARBN A0008703F TORIA VIC N F L M 2 A A G E M T A G RSHALLIN Th e Victorian Flagmarshalling Team A Word from the President Hi, and welcome to another presidential magazine report. Things in the club are running smoothly at William Gaff this time. We have just returned from the Winton V8 round which was a great weekend of racing social media will be used. Thanks with all the spills and excitement trackside. to Suz for the new blog for the club. The Promotions team had a presence at Winton for the irst time with Perry Ballard Katrina Til next Ballard and Karen Legg handing out lyers. Perry time and Katrina worked the promotions lyers on William Sunday at the track and Karen was in Benalla Gaff on Thursday afternoon at the V8 driver signings VFT handing out lyers for the club. A big thank you President from the committee goes out to to the promotions team for doing such a grand job. Also, I must thank Heather Wallace, Winton Raceway and the Benalla Auto Club for allowing the VFT to do this and we hope it’s not the last time thanks again to all of you. -

August 2007 Page 2

———— Holden TORQUE ————————————————————— August 2007 page 2 Dedicated to the founding members of the Torana Club of Victoria, the car that inspired them, and all past and present members of this great club - TCV/HMSCV/HSCCV ———— Holden TORQUE ————————————————————— August 2007 page 3 Welcome to the August 2007 Edition of In this months magazine: Stock Report: page 14 Executive Torque - News from the President, Vice President, Secretary & Treasurer: page 4 Webmaster: page 14 Club Calendar : page 7 RAAF Base Races: page 15 Motorsport - Sandown Sprint: page 9 More Morwell Hillclimb: page 17 Motorsport - Morwell Hillclimb: page 11 Book & DVD Review: page 19 Editors ramblings: page 11 July General Meeting minutes: page 20 Motorkhana & Social: page 12 Membership form: backpage ———— Club TORQUE - Committee 2007 and Club Information ——————————— President Wayne Paola Vice President Glenn Mason [email protected] [email protected] 0431755297 0409436893 Secretary Kylie Kastelic Treasurer Peter Stewart [email protected] [email protected] 0404066616 0407361426 Motorkhana & Frank Rogan Public Officer Ray Cardwell Group5 Rep [email protected] Stock Rep. Glenn Mason SocialRep Frank Rogan [email protected] [email protected] MotorRacing & Greg Black Editor Kim McConchie Rally Rep [email protected] [email protected] 0417542585 ClassicHistoric Richard Wales Membership/Point Kylie Kastelic Registry (03) 9803 7690 score [email protected] 0404066616 Special Events Alan Davies CAMSStateCouncil Rep Wayne Paola [email protected] 0400188249 Magazine Articles and advertisements to be published in the magazine can be submitted via e-mail to the Editor at [email protected] . Microsoft Word format is preferred and each months items must be received by midnight on the second Thursday of each month. -

September 2020

The official magazine of Auckland Motorcycle Club, Inc. SEPTEMBER 2020 In this issue: • Dick Smart – Part 4 • Formula Auckland Returns • Buckets – Back In Action • AMCC AGM & Prize-Giving (Part 2) • Campbell Little • And Lots More ….. 1110 Great South Road, PO Box 22362, Otahuhu, Auckland Ph: 276 0880 EXECUTIVE COMMITTEE 2020 - 2021 Email Phone PATRON Jim Campbell PRESIDENT Greg Percival [email protected] 021 160 3960 VICE PRESIDENT Adam Mitchell [email protected] 021 128 4108 SECRETARY TBA [email protected] TBA TREASURER Paul Garrett [email protected] TBA MEMBERSHIP MXTiming [email protected] and John Catton CLUB CAPTAIN Adam Mitchell [email protected] 021 128 4108 ROAD RACE John Catton [email protected] COMMITTEE Adam Mitchell 021 128 4108 Mark Wigley 027 250 3237 Paul Garrett Tim Sibley Jim Manoah Neal Martin ROAD RACE MX Timing [email protected] 027 201 1177 SECRETARY Nicole Bol GENERAL Glenn Mettam [email protected] 021 160 3960 COMMITTEE Trevor Heaphy 022 647 7899 Philip Kavermann 021 264 8021 Alistair Wilton Juniper White 021 040 3819 MINIATURE ROAD David Diprose [email protected] 021 275 0003 RACE CHIEF FLAG Juniper White [email protected] 021 040 3819 MARSHAL NZIGP REP Trevor Heaphy [email protected] 022 647 7899 MAGAZINE EDITOR Philip Kavermann [email protected] 021 264 8021 & MEDIA MNZ REP Glenn Mettam [email protected] 021 902 849 WEBSITE Johannes Rol [email protected] 021 544 514 Cover Image: Buckets back in action at Hampton Downs PRESIDENT’S REPORT – SEPTEMBER 2020 Hi All, The Wattyl trees around Hampton Downs are out in bloom, signaling that Winter officially finishes on the last day of August ‐ and more importantly, only 20 days to go until we're back racing on the National circuit on the 20th. -

Car Number Team Sponsor Name Driver Name Model 1 Toll Holden

Car Number Team Sponsor Name Driver Name Model 1 Toll Holden Racing Team Garth Tander VE 2 Toll Holden Racing Team Mark Skaife VE 3 Sprint Gas Racing Jason Richards VE 4 Jeld-Wen Motorsport James Courtney BF 5 Ford Performance Racing Mark Winterbottom BF 6 Ford Performance Racing Steven Richards BF 7 Jack Daniel's Racing Todd Kelly VE 9 SP Tools Racing Shane Van Gisbergen BF 11 Jack Daniel's Racing Shane Price VE 12 Team BOC Andrew Jones VE 14 WOW Racing Cameron McConville VE 15 HSV Dealer Team Rick Kelly VE 16 Autobarn Racing Team Paul Dumbrell VE 17 Jim Beam Racing Steven Johnson BF 18 Jim Beam Racing Will Davison BF 021 Team Kiwi Racing Kayne Scott BF 25 Fujitsu Racing Jason Bright BF 26 IRWIN Racing Marcus Marshall BF 33 Val voline Cummins Race Team Lee Holdsworth VE 34 Valvoline Cummins Race Team Michael Caruso VE 39 Supercheap Auto Racing Russell Ingall VE 50 PWR Performance Products Andrew Thompson VE 51 Sprint Gas Racing Greg Murphy VE 55 Rod Nash Racing Tony D'Alberto VE 67 Supercheap Auto Racing Paul Morris VE 88 TeamVodafone Jamie Whincup BF 111 Glenfords Racing Fabian Coulthard BF 777 Ausdrill Ford Rising Stars Racing Michael Patrizi BF 888 TeamVodafone Craig Lowndes BF TOTAL 29 Car Number Team Sponsor Name Driver Model 13 All-Trans Trucks/Gulf Western Oil Colin Sieders AU 19 Gulf Western Oil David Siders BA 23 Gawler Farm Machinery Tim Slade VZ 27 Howard Racing/Novus Capital/National Tyres Karl Reindler BA 28 MW Motorsport TBA BA 29 Summit Fleet Leasing Grant Denyer BA 30 ANT Racing Tony Evangelou BA 35 TAG Motorsport Tony -

Scalextric Aussie V8 Supercars: 42 Cars So Far! (Page 1 of 4)

Scalextric Aussie V8 Supercars: 42 Cars So Far! (Page 1 of 4) Produced by the A.S.R.C.C. for the enjoyment of club members! www.scalextricaustralia.com 2002 Holden 2003 Ford 2003 Holden 2003 Ford C2446 Castrol Perkins Racing C2447 Stone Bros Racing C2519 Garry Rogers Motorsport C2520 Dick Johnson Racing Russell Ingall #8 (9th Place) Marcus Ambrose #4 (Champion) Garth Tander #34 (12th Place) Steven Johnson #17 (16th Place) 2004 Holden 2004 Ford 2004 Ford 2004 Ford C2612 Castrol Perkins Racing C2613 Stone Bros Racing C2614 Stone Bros Racing C2615 Ford Performance Racing Steven Richards #11 (5th Place) Marcus Ambrose #1 (Champion) Russell Ingall #9 (2nd Place) Craig Lowndes #6 (20th Place) 2005 Holden 2005 Ford 2005 Ford 2005 Ford C2692 Paul Weel Racing C2693 Team Betta Electrical C2694 Stone Bros Racing C2695 Ford Performance Racing Greg Murphy #51 (11th Place) Craig Lowndes #888 (2nd Place) Marcus Ambrose #1 (3rd Place) Jason Bright #6 (9th Place) For enquiries on this poster please This poster is possible with contact Dominic Grimes, President, thanks to Scalextric, Southern A.S.R.C.C.: Model Supplies and the [email protected] sponsors of the A.S.R.C.C.: (Version 1 25/08/17) www.slotshop.com.au www.slotscarsalive.com Scalextric Aussie V8 Supercars: 42 Cars So Far! (Page 2 of 4) Produced by the A.S.R.C.C. for the enjoyment of club members! www.scalextricaustralia.com 2006 Ford 2006 Ford 2006 Holden 2006 Holden C2766 Stone Bros Racing C2767 Dick Johnson Racing C2768 Paul Weel Racing C2769 Tasman Motorsport Russell Ingall #1 -

2021 CAR RESULTS : PROLOGUE : PROVISIONAL : OUTRIGHT (12 Jun 2021 11:48)

2021 TATTS FINKE DESERT RACE 2021 CAR RESULTS : PROLOGUE : PROVISIONAL : OUTRIGHT (12 Jun 2021 11:48) Pos Class Car Driver/Co-Driver/Navigator Vehicle Time Gap To Leader Int 1 X2WD 487 TOBY PRICE JOSEPH WEINING MARK 6000 CHEV 360cc 00:04:38.7 DUTTON 2 PRO 15 JOSH HOWELLS ERIC HUME JIMCO 3500TT NISSAN 3500cc 00:04:43.7 + 00:00:05.0 + 00:00:05.0 3 X2WD 413 BEAU ROBINSON SHANE HUTT GEISER BROS TROPHY TRUCK CHEV 6000cc 00:04:47.0 + 00:00:08.3 + 00:00:03.3 4 PRO 27 JOHN TOWERS BRUCE YOUNG JT LUSTRUM HONDA 3.2Lcc 00:04:48.7 + 00:00:10.0 + 00:00:01.7 5 PRO 93 AARON JAMES ALUMICRAFT FORD 3500cc 00:04:54.0 + 00:00:15.3 + 00:00:05.3 6 X2WD 410 GREG GARTNER JAMIE JENNINGS MARK FORD RAPTOR GEISER FORD 6000cc 00:04:54.1 + 00:00:15.4 + 00:00:00.1 HANNAFORD 7 PRO 23 PETER COSTELLO BEN BROOKS JIMCO AUSSIE SPECIAL 3500 CC TOYOTA 00:04:54.7 + 00:00:16.0 + 00:00:00.6 3500cc 8 PROLITE 135 ANDREW MOWLES TEEGAN MOWLES JAG RAZORBACK 2010 BMW 3.5cc 00:04:55.9 + 00:00:17.2 + 00:00:01.2 LEE BAUWENS 9 X2WD 454 BRAD GALLARD DEAN KEYES SCOTT GEISER BROS TROPHY TRUCK CHEV 00:04:56.6 + 00:00:17.9 + 00:00:00.7 MODISTACH 6000CC CHEV 6000cc 10 X4WD 818 HAYDEN BENTLEY HANNAH BENTLEY TROPHY TRUCK RACER ENGINEERING 00:04:58.0 + 00:00:19.3 + 00:00:01.4 VIV COE NISSAN 3.