Seven Autobiographical Accounts of Arriving in New York Andy Warhol

Total Page:16

File Type:pdf, Size:1020Kb

Load more

Recommended publications

-

Repor 1 Resumes

REPOR 1RESUMES ED 018 277 PS 000 871 TEACHING GENERAL MUSIC, A RESOURCE HANDBOOK FOR GRADES 7 AND 8. BY- SAETVEIT, JOSEPH G. AND OTHERS NEW YORK STATE EDUCATION DEPT., ALBANY PUB DATE 66 EDRS PRICEMF$0.75 HC -$7.52 186P. DESCRIPTORS *MUSIC EDUCATION, *PROGRAM CONTENT, *COURSE ORGANIZATION, UNIT PLAN, *GRADE 7, *GRADE 8, INSTRUCTIONAL MATERIALS; BIBLIOGRAPHIES, MUSIC TECHNIQUES, NEW YORK, THIS HANDBOOK PRESENTS SPECIFIC SUGGESTIONS CONCERNING CONTENT, METHODS, AND MATERIALS APPROPRIATE FOR USE IN THE IMPLEMENTATION OF AN INSTRUCTIONAL PROGRAM IN GENERAL MUSIC FOR GRADES 7 AND 8. TWENTY -FIVE TEACHING UNITS ARE PROVIDED AND ARE RECOMMENDED FOR ADAPTATION TO MEET SITUATIONAL CONDITIONS. THE TEACHING UNITS ARE GROUPED UNDER THE GENERAL TOPIC HEADINGS OF(1) ELEMENTS OF MUSIC,(2) THE SCIENCE OF SOUND,(3) MUSICAL INSTRUMENTS,(4) AMERICAN FOLK MUSIC, (5) MUSIC IN NEW YORK STATE,(6) MUSIC OF THE THEATER,(7) MUSIC FOR INSTRUMENTAL GROUPS,(8) OPERA,(9) MUSIC OF OTHER CULTURES, AND (10) HISTORICAL PERIODS IN MUSIC. THE PRESENTATION OF EACH UNIT CONSISTS OF SUGGESTIONS FOR (1) SETTING THE STAGE' (2) INTRODUCTORY DISCUSSION,(3) INITIAL MUSICAL EXPERIENCES,(4) DISCUSSION AND DEMONSTRATION, (5) APPLICATION OF SKILLS AND UNDERSTANDINGS,(6) RELATED PUPIL ACTIVITIES, AND(7) CULMINATING CLASS ACTIVITY (WHERE APPROPRIATE). SUITABLE PERFORMANCE LITERATURE, RECORDINGS, AND FILMS ARE CITED FOR USE WITH EACH OF THE UNITS. SEVEN EXTENSIVE BE.LIOGRAPHIES ARE INCLUDED' AND SOURCES OF BIBLIOGRAPHICAL ENTRIES, RECORDINGS, AND FILMS ARE LISTED. (JS) ,; \\',,N.k-*:V:.`.$',,N,':;:''-,",.;,1,4 / , .; s" r . ....,,'IA, '','''N,-'0%')',", ' '4' ,,?.',At.: \.,:,, - ',,,' :.'v.'',A''''',:'- :*,''''.:':1;,- s - 0,- - 41tl,-''''s"-,-N 'Ai -OeC...1%.3k.±..... -,'rik,,I.k4,-.&,- ,',V,,kW...4- ,ILt'," s','.:- ,..' 0,4'',A;:`,..,""k --'' .',''.- '' ''-. -

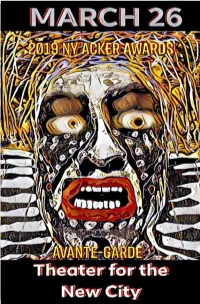

NY ACKER Awards Is Taken from an Archaic Dutch Word Meaning a Noticeable Movement in a Stream

1 THE NYC ACKER AWARDS CREATOR & PRODUCER CLAYTON PATTERSON This is our 6th successful year of the ACKER Awards. The meaning of ACKER in the NY ACKER Awards is taken from an archaic Dutch word meaning a noticeable movement in a stream. The stream is the mainstream and the noticeable movement is the avant grade. By documenting my community, on an almost daily base, I have come to understand that gentrification is much more than the changing face of real estate and forced population migrations. The influence of gen- trification can be seen in where we live and work, how we shop, bank, communicate, travel, law enforcement, doctor visits, etc. We will look back and realize that the impact of gentrification on our society is as powerful a force as the industrial revolution was. I witness the demise and obliteration of just about all of the recogniz- able parts of my community, including so much of our history. I be- lieve if we do not save our own history, then who will. The NY ACKERS are one part of a much larger vision and ambition. A vision and ambition that is not about me but it is about community. Our community. Our history. The history of the Individuals, the Outsid- ers, the Outlaws, the Misfits, the Radicals, the Visionaries, the Dream- ers, the contributors, those who provided spaces and venues which allowed creativity to flourish, wrote about, talked about, inspired, mentored the creative spirit, and those who gave much, but have not been, for whatever reason, recognized by the mainstream. -

Rétrospective Chantal Akerman 31 Janvier – 2 Mars 2018

Rétrospective Chantal Akerman 31 janvier – 2 mars 2018 AVEC LE SOUTIEN DE WALLONIE-BRUXELLES INTERNATIONAL ET LE CONCOURS DU CENTRE WALLONIE BRUXELLES Héritière à la fois de la Nouvelle Vague et du cinéma underground américain, l’œuvre de Chantal Akerman explore avec élégance les notions de frontière et de transmission. Ses films vont de l’essai expérimental (Hotel Monterey), aux récits de la solitude (Jeanne Dielman), en passant par des comédies à l’humour triste (Un divan à New York) et les somptueuses adaptations de classiques littéraires (Proust pour La Captive). CONFÉRENCE et DIALOGUES “CHANTAL AKERMAN : L’ESPACE PENDANT UN CERTAIN TEMPS” PAR JÉRÔME MOMCILOVIC je 01 fév 19h Chantal Akerman a dit souvent son étonnement face à cette formule banale, qui nous vient parfois pour exprimer le plaisir pris un film : ne pas voir le temps passer. De l’appartement du premier film (Saute ma ville, 1968) a celui du dernier (No Home Movie, 2015), des rues traversées par la fiction (Toute une nuit) a celles longées par le documentaire (D’Est), ses films ont suivi une morale rigoureusement inverse : regarder le temps, pour mieux voir l’espace, et nous le faire habiter ainsi en compagnie de tous les fantômes qui le hantent. A la suite de la conférence, à 21h30, projection d’un film choisi par le conférencier : News from Home. Jerome Momcilovic est critique de cinema, responsable des pages cinéma du magazine Chronic’art. Il est l’auteur chez Capricci de Prodiges d’Arnold Schwarzenegger (2016) et, en février 2018, d’un essai sur le cinema de Chantal Akerman Dieu se reposa, mais pas nous. -

This Book Is a Compendium of New Wave Posters. It Is Organized Around the Designers (At Last!)

“This book is a compendium of new wave posters. It is organized around the designers (at last!). It emphasizes the key contribution of Eastern Europe as well as Western Europe, and beyond. And it is a very timely volume, assembled with R|A|P’s usual flair, style and understanding.” –CHRISTOPHER FRAYLING, FROM THE INTRODUCTION 2 artbook.com French New Wave A Revolution in Design Edited by Tony Nourmand. Introduction by Christopher Frayling. The French New Wave of the 1950s and 1960s is one of the most important movements in the history of film. Its fresh energy and vision changed the cinematic landscape, and its style has had a seminal impact on pop culture. The poster artists tasked with selling these Nouvelle Vague films to the masses—in France and internationally—helped to create this style, and in so doing found themselves at the forefront of a revolution in art, graphic design and photography. French New Wave: A Revolution in Design celebrates explosive and groundbreaking poster art that accompanied French New Wave films like The 400 Blows (1959), Jules and Jim (1962) and The Umbrellas of Cherbourg (1964). Featuring posters from over 20 countries, the imagery is accompanied by biographies on more than 100 artists, photographers and designers involved—the first time many of those responsible for promoting and portraying this movement have been properly recognized. This publication spotlights the poster designers who worked alongside directors, cinematographers and actors to define the look of the French New Wave. Artists presented in this volume include Jean-Michel Folon, Boris Grinsson, Waldemar Świerzy, Christian Broutin, Tomasz Rumiński, Hans Hillman, Georges Allard, René Ferracci, Bruno Rehak, Zdeněk Ziegler, Miroslav Vystrcil, Peter Strausfeld, Maciej Hibner, Andrzej Krajewski, Maciej Zbikowski, Josef Vylet’al, Sandro Simeoni, Averardo Ciriello, Marcello Colizzi and many more. -

Casting Director Cv 2018

LEANNE FLINN CASTING DIRECTOR EMAIL: [email protected] MOBILE: 07740 649 722 WEBSITE: LEANNEFLINN.COM *Award winning Freelance Casting Director since 2009. Experienced casting commercials, music videos, shorts and feature films for production companies including Partizan, HSI, Pulse, Somesuch, MJZ, Sonny and for directors including Daniel Wolfe, Ben Drew, Yann Demange, Kim Kehrig, Nick Gordon, Fredrik Bond and Yorgos Lanthimos. Specialising in Street Casting and traditional casting methods. CDA member since 2016. *Gold and Silver Ciclope 2017/ British Arrows/ 2x D&AD pencils/ 2x CDA awards CASTING DIRECTOR First TV credit was for the first series of ‘People Just Do Nothing’ a BBC3 Comedy mockumentary produced by Roughcut TV. (street casting leads and traditional casting) A selection of my credits include: ShortFlix ‘ Ladies Day’ Dir Abena Taylor Short Film/TV Delaval/ Sky arts 2018 ShortFlix ‘Together, they smoke’ Dir Henry Gale Short Film/TV Delaval/ Sky arts 2018 ShortFlix ‘Losing It’ Dir Ben Robins Short Film/TV Delaval/ Sky arts 2018 Storm Dir Rob Brown TV Pilot Wildseed New Year Dir Animation BBC Sounds Ident Dir Megaforce Ident Riff Raff 2018 Chaka Khan ‘Like Sugar’ Dir Kim Gehrig Music Video Somesuch 2018 Dettol Dir Christopher Hill Online Dirty Films 2018 BT Sport ‘Heroes’ Dir Fredrik Bond TVC Sonny London 2018 Alzheimers Dir Aoife McArdle Online Somesuch 2018 Dutch Lottery Dir Online TBWA 2018 The FA announcement Film Dir Dan Emmerson Online Somesuch 2018 Hovis ‘Soft White’ Dir Byron Quandary TVC Dirty Films 2018 KFC -

English Song Booklet

English Song Booklet SONG NUMBER SONG TITLE SINGER SONG NUMBER SONG TITLE SINGER 100002 1 & 1 BEYONCE 100003 10 SECONDS JAZMINE SULLIVAN 100007 18 INCHES LAUREN ALAINA 100008 19 AND CRAZY BOMSHEL 100012 2 IN THE MORNING 100013 2 REASONS TREY SONGZ,TI 100014 2 UNLIMITED NO LIMIT 100015 2012 IT AIN'T THE END JAY SEAN,NICKI MINAJ 100017 2012PRADA ENGLISH DJ 100018 21 GUNS GREEN DAY 100019 21 QUESTIONS 5 CENT 100021 21ST CENTURY BREAKDOWN GREEN DAY 100022 21ST CENTURY GIRL WILLOW SMITH 100023 22 (ORIGINAL) TAYLOR SWIFT 100027 25 MINUTES 100028 2PAC CALIFORNIA LOVE 100030 3 WAY LADY GAGA 100031 365 DAYS ZZ WARD 100033 3AM MATCHBOX 2 100035 4 MINUTES MADONNA,JUSTIN TIMBERLAKE 100034 4 MINUTES(LIVE) MADONNA 100036 4 MY TOWN LIL WAYNE,DRAKE 100037 40 DAYS BLESSTHEFALL 100038 455 ROCKET KATHY MATTEA 100039 4EVER THE VERONICAS 100040 4H55 (REMIX) LYNDA TRANG DAI 100043 4TH OF JULY KELIS 100042 4TH OF JULY BRIAN MCKNIGHT 100041 4TH OF JULY FIREWORKS KELIS 100044 5 O'CLOCK T PAIN 100046 50 WAYS TO SAY GOODBYE TRAIN 100045 50 WAYS TO SAY GOODBYE TRAIN 100047 6 FOOT 7 FOOT LIL WAYNE 100048 7 DAYS CRAIG DAVID 100049 7 THINGS MILEY CYRUS 100050 9 PIECE RICK ROSS,LIL WAYNE 100051 93 MILLION MILES JASON MRAZ 100052 A BABY CHANGES EVERYTHING FAITH HILL 100053 A BEAUTIFUL LIE 3 SECONDS TO MARS 100054 A DIFFERENT CORNER GEORGE MICHAEL 100055 A DIFFERENT SIDE OF ME ALLSTAR WEEKEND 100056 A FACE LIKE THAT PET SHOP BOYS 100057 A HOLLY JOLLY CHRISTMAS LADY ANTEBELLUM 500164 A KIND OF HUSH HERMAN'S HERMITS 500165 A KISS IS A TERRIBLE THING (TO WASTE) MEAT LOAF 500166 A KISS TO BUILD A DREAM ON LOUIS ARMSTRONG 100058 A KISS WITH A FIST FLORENCE 100059 A LIGHT THAT NEVER COMES LINKIN PARK 500167 A LITTLE BIT LONGER JONAS BROTHERS 500168 A LITTLE BIT ME, A LITTLE BIT YOU THE MONKEES 500170 A LITTLE BIT MORE DR. -

Mle) Speech Rhythm

CORE Metadata, citation and similar papers at core.ac.uk Provided by Goldsmiths Research Online 452 Christopher S. Lee, Lucinda Brown, & Daniel Mu¨llensiefen THE MUSICAL IMPACT OF MULTICULTURAL LONDON ENGLISH (MLE) SPEECH RHYTHM CHRISTOPHER S. LEE,LUCINDA BROWN,& Ollen (2003), McGowan and Levitt (2011), and Sada- DANIEL MU¨ LLENSIEFEN kata (2006) yielded the finding that the degree of vocalic University of London, London, United Kingdom durational variability in a language is reflected in the degree of durational variability in the melodies pro- THERE IS EVIDENCE THAT AN EMERGING VARIETY OF duced by native speakers, across a wide variety of dia- English spoken by young Londoners—Multicultural lects, languages, and musical styles, though more London English (MLE)—has a more even syllable detailed findings from European art music have also rhythm than Southern British English (SBE). Given shown how stylistic factors (in this case probably findings that native language rhythm influences the reflecting non-native language rhythm) may exert an production of musical rhythms and text setting, we overriding counterinfluence (Daniele & Patel, 2004, investigated possible musical consequences of this 2013; Hansen, Sadakata, & Pearce, 2016; Huron & development. We hypothesized that the lower vocalic Ollen, 2003; Patel & Daniele, 2003b; VanHandel & Song, durational variability in MLE and (putatively) less 2010). These similarities appear to be salient to listeners: salient stress distinctions would go along with a prefer- Hannon (2009) showed that native and non-native ence by MLE speakers for lower melodic durational English listeners were able to classify French and variability and a higher tolerance for stress mismatches English folk songs according to their language of origin (the non-coincidence of stress/beat strong-weak pat- solely on the basis of their rhythms. -

Centro Universitario Europeo Per I Beni Culturali Ravello

Centro Universitario Europeo per i Beni Culturali Ravello Territori della Cultura Rivista on line Numero 4 Anno 2011 Iscrizione al Tribunale della Stampa di Roma n. 344 del 05/08/2010 Centro Universitario Europeo per i Beni Culturali Sommario Ravello Comitato di redazione 5 La nuova sfida di RAVELLO LAB 6 Alfonso Andria Beni Culturali e conflitti armati 8 Pietro Graziani Conoscenza del patrimonio culturale Maria Rita Sanzi Di Mino Il sacro e l’ambiente 12 nel mondo antico Claudio La Rocca Lo scavo archeologico 16 di Piazza Epiro a Roma Lina Sabino Maiori (SA), Complesso Abbaziale 20 di Santa Maria de Olearia Roger Lefèvre L’enseignement des sciences 26 du patrimoine culturel dans un monde en changement: une Conférence à Varsovie et un Cours à Ravello en 2011 28 Massimo Pistacchi Storia della fonografia Cultura come fattore di sviluppo Stefania Chirico, Giuseppe Pennisi Strategie gestionali per la valorizzazione delle risorse culturali: 38 il caso di Ravenna Teresa Gagliardi Costruire in Costiera Amalfitana: 54 ieri, oggi e domani? Fabio Pollice, Giulia Urso Le città come fucine culturali. Per una lettura critica delle politiche 64 di rigenerazione urbana Sandro Polci Cult economy: un nuovo/antico driver 72 per i territori minori Metodi e strumenti del patrimonio culturale Maurizio Apicella From the Garden of the Hesperides 84 to the Amalfi Coast. The culture of lemons Matilde Romito Artiste straniere a Positano 90 fra gli anni Venti e gli anni Sessanta Luciana Bordoni Tecnologie 106 e valori culturali Antonio Gisolfi La risoluzione del labirinto 112 Simone Bozzato Territorio, formazione scolastica e innovazione. Attuazione, nella provincia Copyright 2010 © Centro Universitario di Salerno, di un modello applicativo 116 Europeo per i Beni Culturali finalizzato a ridurre il digital divide Territori della Cultura è una testata iscritta al Tribunale della Stampa di Roma. -

“Just a Dream”: Community, Identity, and the Blues of Big Bill Broonzy. (2011) Directed by Dr

GREENE, KEVIN D., Ph.D. “Just a Dream”: Community, Identity, and the Blues of Big Bill Broonzy. (2011) Directed by Dr. Benjamin Filene. 332 pgs This dissertation investigates the development of African American identity and blues culture in the United States and Europe from the 1920s to the 1950s through an examination of the life of one of the blues’ greatest artists. Across his career, Big Bill Broonzy negotiated identities and formed communities through exchanges with and among his African American, white American, and European audiences. Each respective group held its own ideas about what the blues, its performers, and the communities they built meant to American and European culture. This study argues that Broonzy negotiated a successful and lengthy career by navigating each groups’ cultural expectations through a process that continually transformed his musical and professional identity. Chapter 1 traces Broonzy’s negotiation of black Chicago. It explores how he created his new identity and contributed to the flowering of Chicago’s blues community by navigating the emerging racial, social, and economic terrain of the city. Chapter 2 considers Broonzy’s music career from the early twentieth century to the early 1950s and argues that his evolution as a musician—his lifelong transition from country fiddler to solo male blues artist to black pop artist to American folk revivalist and European jazz hero—provides a fascinating lens through which to view how twentieth century African American artists faced opportunities—and pressures—to reshape their identities. Chapter 3 extends this examination of Broonzy’s career from 1951 until his death in 1957, a period in which he achieved newfound fame among folklorists in the United States and jazz and blues aficionados in Europe. -

Vol. 1, No.1, October 2015

Vol. 1, No.1, October 2015 It all happened at ST Marks Place: Abbie Hoffman invented the Yippies at No. 30; Andy Warhol, the Velvet Underground, and Jimi Hendrix performed at the experimental nightclub Electric Circus. Gallery 51X backed eighties-era graffiti artists like Keith Harlng and Basquiat. At No. 77 Leon Trotsky edited the dissident newspaper Novy Mir in 1917. Years later in the same building, the poet W.H. Auden and the artist Larry Rivers lived below. At the Holiday Coctail Lounge, Alan Ginsberg drank. Madonna was there, These are just a few of the characters that haunt Haiku - Poem by Allen Ginsberg Drinking my tea Without sugar - No difference. The sparrow shits upside down - ah! my brain & eggs Mayan head in a Pacific driftwood bole - Someday I'll live in N.Y. Looking over my shoulder my behind was covered with cherry blossoms. Winter Haiku I didn't know the names of the flowers - now my garden is gone. I slapped the mosquito and missed. What made me do that? Reading haiku I am unhappy, longing for the Nameless. A frog floating in the drugstore jar: summer rain on grey pavements. (after Shiki) On the porch in my shorts; auto lights in the rain. Another year has past - the world is no different. ST. MARKS BACK IN THE DAY By 1963, Cue's New York: A Leisurely Guide to Manhattan, was already sending folks to the East Village for its cafes, galleries, and charming Beatniks—people like Jack Kerouac, William S. Burroughs, and Allen Ginsberg, a longtime area resident and denizen of Gem Spa at the corner of St. -

Le Velo Dans L'art

LE VELO DANS L’ART Claude Monet, Jean Monet sur son cheval à bascule, 1872 Jean Metzinger, Au vélodrome, 1912 Marcel Duchamp, Roue de bicyclette, 1913 Natalia Goncharova, Le cycliste, 1913 Jean Métzinger, Au vélodrome, 1914 Gerardo Dottori, Cycliste, 1914 Fortunato Depero, Ciclista moltiplicato, 1924 Meret Oppenheim, La selle d’abeilles, 1930 Herbert List, Allemagne, mer Baltique, 1930 Pablo Picasso, Tête de taureau, 1942 Fernand Léger, Les belles Cyclistes, 1944 Fernand Léger, Les deux guidons, 1945 Fernand Léger, L’homme au vélo, 1947 Fernand Léger, Les loisirs sur fond rouge, 1949 Kees Van Dongen, La bicyclette sous la pluie, 1947 Bernard Buffet, L’acrobate à la bicyclette, 1955 Jean Tinguely, Tricycle, 1960 Jean Tinguély, Cyclograveur, 1960 Robert Filliou, groupe Fluxus, Danse poème aléatoire, 1962 Marc Chagall, Le cirque, les cyclistes, 1965 Jean-Michel Basquiat, GEM SPA, 1982 Philippe Ramette, Sans titre (Mobylette crucifiée), 1987 Bengt-Göran Broström, ASEA strömmen, 1989 Claes Oldenbourg et Coosje Van Bruggen, La bicyclette ensevelie, 1990 César, Compression de vélos, 1990 Gabriel Orozco, Four bicycles, 1994 Jean-Bernard Métais, Le Tour de France dans les Pyrénées, 1995-1996 Vincent Lamouroux et Raphaël Zarka, Pentacycle, 2002 Chris Gilmour, Bike, sculpture hyperréaliste en carton, 2003 Chris Gilmour Ai Weiwei, Forever bicycles, 2003 Alain Sechasen, Le Cycliste de Bruxelles, 2005 Dominique Blais, Marclay’s Bike, 2006 Mark Grive, Bike Arch, 2007 Michael Gumhold, Movement #1913– 2007, 2007 Dorothy Shoes, The passenger, 2007 Kevin Cyr, Camping Bike, 2008 Alix Petit, Pissenlits, 2009 Marion Laval-Jeantet et Benoît Mangin, Unrooted Tree (Arbre sans racines) ou la Machine à faire parler les arbres, 2009 Ji Lee, Duchamp Reloaded, 2009 Richard Fauguet, Sans titre, 2010 Mark Grieve, Cyclisk, 2010 Monsieur BMX, Velo mural, street art, Montpellier, 2010 Alain Delorme, Totem, 2010, photomontage Alain Delorme Ai Weiwei, Forever bicycles, 2011 Ron Arad, Soft Ride, 2011 Benedetto Bufalino, La moto vélo, 2012 https://www.benedettobufalino.com/ John A. -

2018 Innovation Et Créativité Autour De L'œuvre Du Peintre Jean-Michel Basquiat

2017- 2018 Séminaire Innover en management Innovation et créativité autour de l’œuvre du peintre Jean-Michel Basquiat Compte-rendu séance du 7 février 2018, par Albert David Intervention de Dominique LAFON Fondateur de CayaK Innov Dominique Lafon raconte sa rencontre avec Basquiat, via un tableau vu par hasard dans une galerie new-yor- kaise. Basquiat est obsédant. « Il vaut mieux se consu- mer que de s’éteindre à petit feu » (Kurt Kobain). Quelques citations en guise d’introduction. • Jacques Hadamard : « l’inventeur ne connaît pas la prudence ». Hadamard écrit des choses sur l’inventivité et la créativité en mathématiques. Impru- reprend des éléments de l’œuvre de Vinci. Ce tableau dence transgressive. montre une sorte de filiation. • Henri Poincaré : « Illuminations subites ». Vie de Basquiat : né en 1960 à Brooklyn. Père Haï- Poincaré a parlé le premier du rôle de l’inconscient en tien mère portoricaine. Forte souffrance dans l’enfance mathématiques. morale mais aussi physique (battu par son père). Evé- • Paul Valéry : « Dieu sait quelles géométries l’in- nement majeur chez Basquiat : il est renversé par vention des miroirs a pu engendrer chez les mouches». une voiture, on lui enlève la rate. S’ennuie à l’hôpi- Donc influence du contexte. tal. Demande un livre. Sa mère lui rapporte un livre… d’anatomie (il n’y avait que des librairies de médecine • Albert Einstein : « des idées j’en ai si peu ». dans le quartier). Basquiat dessine tout le temps. Ren- contre un grapheur (Al Diaz) en 1977. « On est un Un premier dessin de Basquiat : Tesla vs Edison (guerre beau duo, on va secouer cette ville ».