AFL-CIO and Solidarity Center Joint Submission in Response to the Request for Comment on Guidelines

Total Page:16

File Type:pdf, Size:1020Kb

Load more

Recommended publications

-

Executive Council Report

ExEcutivE council REpoRt FoR ThE PaST FouR YEaRS, the Executive Council of the AFL-CIO, which is the governing body of the federation between conventions, has coordinated the work of our movement to reverse the growing power of giant corporations and special interests, while advancing the crucial needs of working families and driving programs to build a people-powered future for America. We deployed multiple approaches to grow and strengthen our movement. We seized opportunities to make working family priorities central in our nation and the global economy. And we worked to build a unified labor movement with the power to take on the tremendous challenges before us. The AFL-CIO Executive Council is constitutionally charged with reporting on the activities of the AFL-CIO and its affiliates to each Convention. It is with great respect for the delegates to our 26th Constitutional Convention that we present this report on highlights of the past four years. CONTENTS Growing and strengthening the union Movement 17 putting Working Family priorities at center stage 26 unifying our Movement 39 AFL-CIO CONVENTION • 2009 15 16 AFL-CIO CONVENTION • 2009 Growing and Strengthening the Union Movement At ouR 2005 ConVEnTIon, the AFL-CIO In 2005, we adopted a comprehensive recognized the imperative to do much more to resolution calling for the AFL-CIO and its affiliates support and stimulate the organizing of new to devote even more resources, research and members by affiliates and to enact federal staff to helping workers join unions and bargain. legislation to curtail anti-union activities by Since that time, affiliates have significantly employers and restore the freedom of workers increased funding and operations to join unions and bargain for a better life. -

Janice Fine, Page 1

Janice Fine, Page 1 JANICE FINE Associate Professor, Rutgers, The State University of New Jersey 50 Labor Way, New Brunswick, NJ 08901 (848) 932-1746, office (617) 470-0454, cell [email protected] Research and Teaching Fields Innovation and change in the U.S. labor movement; worker centers, new forms of unionism and alternative forms of organization among low-wage workers; community organizing and social movements; immigration: history, theory, policy and political economy; immigrant workers and their rights, US and comparative immigration policy and unions in historical and contemporary perspective, labor standards regulation and enforcement, government oversight, privatization. Education Massachusetts Institute of Technology Ph.D., Political Science January, 2003 (American Politics, Public Policy, Political Economy, Industrial Relations) University of Massachusetts, Boston B.A., 1989, Labor Studies/Community Planning Professional Experience April 2011- Rutgers University, Associate Professor, School of Management and Labor Relations July 2005-April 2011 Rutgers University, Assistant Professor, School of Management and Labor Relations 2003-2005 Economic Policy Institute, Principal Investigator, national study of immigrant worker centers Publications Books No One Size Fits All: Worker Organization, Policy, and Movement in a New Economic Age, LERA 2018 Research Volume, ISBN: 978-0-913447-16-1, Editor, with co-editors: Linda Burnham, Research Fellow, National Domestic Workers Alliance; Kati Griffith, Cornell University; Minsun Ji, University of Colorado, Denver; Victor Narro, UCLA Downtown Labor Center; and Steven Pitts, UC Berkeley Labor Center Worker Centers: Organizing Communities at the Edge of the Dream, Cornell University Press ILR Imprint, 2006. http://www.cornellpress.cornell.edu Nominee, UALE Best Published Book in Labor Education, 2006. -

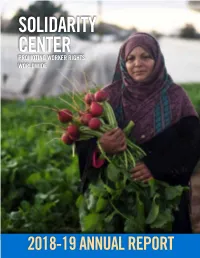

2018-19 Annual Report

SOLIDARITY CENTER PROMOTING WORKER RIGHTS WORLDWIDE 2018-19 ANNUAL REPORT The Solidarity Center is the largest U.S.-based international worker rights organization helping workers attain safe and healthy workplaces, family-supporting wages, dignity on the job and greater equity at work and in their community. Allied with the AFL-CIO, the Solidarity Center assists workers across the globe as, together, they fight discrimination, exploitation and the systems that entrench poverty—to achieve shared prosperity in the global economy. The Solidarity Center acts on the fundamental principle that working people can, by exercising their right to freedom of association and forming trade unions and democratic worker rights organizations, collectively improve their jobs and workplaces, call on their governments to uphold laws and protect human rights, and be a force for democracy, social justice and inclusive economic development. Our Mission: Empowering workers to raise their voices for dignity on the job, justice in their communities and greater equality in the global economy. The Solidarity Center Education Fund is a registered charitable organization tax-exempt under Section 501(c)(3) of the Internal Revenue Code. Contributions are tax-deductible to the extent of applicable laws. A summary of activities from July 2018 to December 2019 and financial highlights for the year ending November 30, 2019, are described in this report. Editors: Carolyn Butler, Tula Connell, Kate Conradt Design: Deepika Mehta Copyright by the Solidarity Center 2019 All rights reserved. ON THE COVER: In her 60s, Etaf Awdi Hamdi Eqdeeh works on farms near Gaza, Palestine, to help support her family. She must visit local farms daily to find temporary jobs. -

Tom Kahn and the Fight for Democracy: a Political Portrait and Personal Recollection

Tom Kahn and the Fight for Democracy: A Political Portrait and Personal Recollection Rachelle Horowitz Editor’s Note: The names of Tom Kahn and Rachelle Horowitz should be better known than they are. Civil rights leader John Lewis certainly knew them. Recalling how the 1963 March on Washington was organised he said, ‘I remember this young lady, Rachelle Horowitz, who worked under Bayard [Rustin], and Rachelle, you could call her at three o'clock in the morning, and say, "Rachelle, how many buses are coming from New York? How many trains coming out of the south? How many buses coming from Philadelphia? How many planes coming from California?" and she could tell you because Rachelle Horowitz and Bayard Rustin worked so closely together. They put that thing together.’ There were compensations, though. Activist Joyce Ladner, who shared Rachelle Horowitz's one bedroom apartment that summer, recalled, ‘There were nights when I came in from the office exhausted and ready to sleep on the sofa, only to find that I had to wait until Bobby Dylan finished playing his guitar and trying out new songs he was working on before I could claim my bed.’ Tom Kahn also played a major role in organising the March on Washington, not least in writing (and rewriting) some of the speeches delivered that day, including A. Philip Randolph’s. When he died in 1992 Kahn was praised by the Social Democrats USA as ‘an incandescent writer, organizational Houdini, and guiding spirit of America's Social Democratic community for over 30 years.’ This account of his life was written by his comrade and friend in 2005. -

American Center for International Labor Solidarity/AFL-CIO Copyright © May 2003 by American Center for International Labor Solidarity

JJUSTICEUSTICE FFOROR AALLLL AA GuideGuide toto WorkerWorker RightsRights inin thethe GlobalGlobal EconomyEconomy American Center for International Labor Solidarity/AFL-CIO Copyright © May 2003 by American Center for International Labor Solidarity All rights reserved Printed in the United States of America American Center for International Labor Solidarity 1925 K Street, NW Suite 300 Washington, DC 20006 www.solidaritycenter.org The American Center for International Labor Solidarity, or the Solidarity Center, is a non-profit organization established to provide assistance to workers who are struggling to build democratic and independent trade unions around the world. It was established in 1997 through the consolidation of four regional AFL-CIO institutes. Working with unions, non- governmental organizations and other community partners, the Solidarity Center supports programs and projects to advance worker rights and promote broad-based, sustainable economic development around the world. Cover design by Fingerhut, Powers, Smith & Associates, Inc. Photos courtesy of the International Labor Organization JUSTICEJUSTICE FORFOR ALLALL A Guide to Worker Rights in the Global Economy American Center for International Labor Solidarity/AFL-CIO May 2003 Funding provided by a grant from the National Endowment for Democracy TABLE OF CONTENTS Introduction The State of Worker Rights Today xiii Chapter 1 Worker Rights Standards and Violation Checklist 1 ■ Freedom of Association (ILO Convention No. 87) 3 ■ Right to Organize and Bargain Collectively (ILO Convention 10 No. 98) ■ Forced Labor (ILO Conventions No. 29 and No. 105) 14 ■ Child Labor (ILO Conventions No. 138 and No. 182) 17 ■ Discrimination (Equality in Employment and Occupation) 23 (ILO Conventions No. 100 and No. 111) ■ Acceptable Conditions of Work (ILO Conventions No. -

You Wouldn't Steal a Donut, So Why Would You Steal a Digital Record?

Label Letter Vol. XXXV, No. 2 Mar-Apr 2010 Union Label & Service Trades Department, AFL-CIO You Wouldn’t Steal a Donut, So Why Would You Steal a Digital Record? fair day’s work for a fair day’s of Professionals, unions in the entertain- wage. Securing that wage for mem- ment industry recently won unanimous bers is the fi rst duty of every union, support from the AFL-CIO Executive Ain manufacturing, construction, Council for a strongly worded resolution transportation, sports, government and to increase public awareness of the scope entertainment. of the problem of intellectual property So, think of George Clooney, Denzel theft. The resolution pledges labor’s sup- Washington, Beyonce, Lady Ga Ga, Peyton port for government policies to counter- Manning, Bono, Bruce Springsteen, Katie act digital piracy and encourages union Couric, or the stunt driver in your favor- members to respect copyright law—and ite action movie as just another dues as a matter of union solidarity—urges payer, just like bus driver, bakery worker, union members to never illegally down- a machinist or a plumber. load or stream pirated content, or pur- Theft isn’t a big problem for bus driv- chase illegal CDs and DVDs. How’s That ‘Buy ers, bakers, machinists or plumbers, but Although the term “show business” con- it is for show business workers. Your jures up images of lavish lifestyles, the real American’ Thing Working favorite movie personalities, singers and work of show business involves millions of Out on Wind Energy? entertainers are losing billions of dol- people who live a middle class existence, lars to thieves—people who steal their with families, kids who need braces, homes “Renewables” are the corner- work—and they’ve asked their unions to and car payments. -

Honor Mike Brown

Irán: ¿Guerra de EUA contra Siria? ● Hiroshima y Nagasaki 12 Workers and oppressed peoples of the world unite! workers.org Vol. 57, No. 34 August 27, 2015 $1 FREE CHELSEA MANNING! WW commentary, page 6 Native Nations resist EPA’s toxic destruction By Chris Fry King Mine near Silverton, Colo., excava- level that requires municipal water sup- tles in the river bottom, only to be stirred tors hired by the federal Environmental pliers to shut down. Cadmium was mea- up by future storms and washed down- Corn, melons, squashes and other Protection Agency breached a wall at the sured at 6.13 ppb (safe limit: 5 ppb); arse- stream. This contamination may last for crops, along with sheep and cattle — mine, causing 3 million gallons of yel- nic at 264 ppb (safe limit: 10 ppb); iron at years. these are what the Diné (Navajo) farmers low-orange waste water to be dumped 326,000 ppb (safe limit: 1,000 ppb); cop- Particularly hard hit is the Navajo Res- grow and raise along the San Juan River into nearby Cement Creek, which flows per at 1,120 ppb (safe limit: 1,000 ppb); ervation, the largest Indigenous territory in the Navajo Reservation in New Mexi- into the Animas River and then into the and manganese at 3,040 ppb (safe limit: in the country. Stretching across por- co. They use the water from the river to San Juan River. 50 ppb). Elevated levels of zinc, berylli- tions of Utah, New Mexico and Arizona, irrigate their crops and provide water for Since then, toxic heavy metals have um and aluminum have also been found. -

Executive Council Report • 2001

Executive Council Executive Report A FL-CIO• TWENTY-FOURTH BIENNIAL CONVENTION• 2001 Contents President’s Report 4 Secretary-Treasurer’s Report 8 Executive Vice President’s Report 12 Executive Council Report to the Convention 16 Winning a Voice at Work 17 People-Powered Politics 25 A Voice for Workers in the Global Economy 31 Building a Strong Union Movement in Every State and Community 38 Trade and Industrial Departments 48 Building and Construction Trades Department 49 Food and Allied Service Trades Department 54 Maritime Trades Department 57 Metal Trades Department 62 Department for Professional Employees 66 Transportation Trades Department 72 Union Label and Service Trades Department 78 Deceased Brothers and Sisters 83 Union Brothers and Sisters Lost to Terrorism 91 President’s Report photo box Most important, we have the strength that comes of solidarity— of shared values and priorities that make us one movement, united. JOHN J. SWEENEY 4 EXECUTIVE COUNCIL REPORT photo box hen we last gathered two years ago, at relief centers, in hospitals and at the ghastly none of us could have guessed what the mound of rubble that had been the World Trade Wfuture had in store for us—as workers, as union Center. A 30-year firefighter sobbed on my shoul- leaders, as a nation. der. A nurse simply laid her face in her hands and Although its bounty did not extend to all cried. Like their brothers and sisters responding working families, our economy then was robust. to the tragedy, they were devastated—but they The presidential administration generally was were strong. receptive to our working families agenda and They were heroes. -

Organized Labor and US Foreign Policy

Florida International University FIU Digital Commons FIU Electronic Theses and Dissertations University Graduate School 11-1-2012 Organized Labor and U.S. Foreign Policy: The Solidarity Center in Historical Context George Nelson Bass III Florida International University, [email protected] DOI: 10.25148/etd.FI12113003 Follow this and additional works at: https://digitalcommons.fiu.edu/etd Recommended Citation Bass, George Nelson III, "Organized Labor and U.S. Foreign Policy: The oS lidarity Center in Historical Context" (2012). FIU Electronic Theses and Dissertations. 752. https://digitalcommons.fiu.edu/etd/752 This work is brought to you for free and open access by the University Graduate School at FIU Digital Commons. It has been accepted for inclusion in FIU Electronic Theses and Dissertations by an authorized administrator of FIU Digital Commons. For more information, please contact [email protected]. FLORIDA INTERNATIONAL UNIVERSITY Miami, Florida ORGANIZED LABOR AND U.S. FOREIGN POLICY: THE SOLIDARITY CENTER IN HISTORICAL CONTEXT A dissertation submitted in partial fulfillment of the requirements for the degree of DOCTOR OF PHILOSOPHY in POLITICAL SCIENCE by G. Nelson Bass III 2012 To: Dean Kenneth G. Furton College of Arts and Science This dissertation, written by G. Nelson Bass III, and entitled Organized Labor and U.S. Foreign Policy: The Solidarity Center in Historical Context, having been approved in respect to style and intellectual content, is referred to you for judgment. We have read this dissertation and recommend that it be approved. _______________________________________ Guillermo J. Grenier _______________________________________ Felix Martin _______________________________________ Nicol C. Rae _______________________________________ Richard Tardanico _______________________________________ Ronald W. Cox, Major Professor Date of Defense: November 1, 2012 The dissertation of G. -

May 24, 2018, Vol. 60, No. 21

Brasil y represión 12 Workers and oppressed peoples of the world unite! workers.org Vol. 60, No. 21 May 24, 2018 $1 North Carolina Public education workers flood state capital By Stephanie Lormand Raleigh, N.C. Fury over Gaza massacre 3, 11 May 16 — Almost 20,000 teachers and supporters rallied today in North Carolina’s capital to defend pub- lic education. The protest closed more than 42 school districts, affected about 67 percent of the state’s public school students, and canceled classes for more than 1 million students. The North Carolina Association of Educators called for the “March for Students and Rally for Respect” with the #ItsPersonal hashtag, asking teachers to “come to the first day of the General Assembly short session.” Teachers responded by paying $50 for a legally protect- ed “personal day” and mobilizing to get to Raleigh. Though the march permit included sidewalks only, people took to the streets by the thousands. They swarmed the former Capitol building, overwhelming the statues and monuments to the old guards of white supremacy. Their numbers wrapped around both sides of the current legislative building, from the front doors around to the back. The crowd poured through the capital in a sea of red shirts, the emblem of education worker struggles popu- larized by the #RedForEd teachers of Arizona. Preced- ing today’s action were massive education worker strug- gles in West Virginia, Kentucky, Oklahoma, Arizona, Colorado and Puerto Rico. Mainstream media focused on the supposed primary motivation of North Carolina’s movement as low teacher salaries. Low pay was certainly a factor, but both liberal and right-wing conservative politicians deliberately nar- rowed the rally into a single-line issue rather than admit- WW PHOTO: JOE PIETTE ting the statewide inequities of public school funding. -

Solidarity and Contention

Movement Theory and International Labor Solidarity1 Henry J. Frundt Abstract As international labor solidarity becomes an important counterweight to corporate globalization, practitioners can benefit from guidance that social movement theory provides. This study applies three strands of movement theory to actual and potential cross-border strategies in the Americas. It explores the structural relevance of political opportuni- ties, the mobilization of networks as a resource, and the emphasis by New Social Movement theory on framing and reflexive identity. It discovers that each strand offers important insights, one clarifying limitations, a second demarcating and cultivating supporters, and a third motivating participation. Taken together, the strands comprise a dynamic basis for solidarity that enriches organizing strategies and gains measurable victories. hen the International Textile, Garment, and Leather Workers WFederation (ITGLWF) approached David Morales regarding the possibility of organizing in the nation’s maquila sector, Morales, leader of FESTRAS, a Guatemalan food workers’ federation, pondered the proposal. The ITGWLWF offered its support because FESTRAS was in the best position to engage clothing workers. Morales knew that FESTRAS had a solid reputation, but its affiliates included no clothing unions and very few female workers, so other militant federations might do a better job than FESTRAS. On the other hand, despite numerous attempts, those federations had failed to sustain campaigns. What strategic guidance could Morales and ITGLWF leaders anticipate if they collaborated to unionize this very recalcitrant sector? The strategic guidance these labor leaders sought encompasses an es- sential aspect of international labor solidarity: furnishing ingredients for a successful organizing campaign. Various authors have well summarized what ——————— LABOR STUDIES JOURNAL, Vol. -

The Voyage of the Neptune Jade: the Perils and Promises of Transnational Labor Solidarity

University at Buffalo School of Law Digital Commons @ University at Buffalo School of Law Journal Articles Faculty Scholarship Winter 1-1-2004 The Voyage of the Neptune Jade: The Perils and Promises of Transnational Labor Solidarity James B. Atleson University at Buffalo School of Law Follow this and additional works at: https://digitalcommons.law.buffalo.edu/journal_articles Part of the Labor and Employment Law Commons Recommended Citation James B. Atleson, The Voyage of the Neptune Jade: The Perils and Promises of Transnational Labor Solidarity, 52 Buff. L. Rev. 85 (2004). Available at: https://digitalcommons.law.buffalo.edu/journal_articles/807 This Article is brought to you for free and open access by the Faculty Scholarship at Digital Commons @ University at Buffalo School of Law. It has been accepted for inclusion in Journal Articles by an authorized administrator of Digital Commons @ University at Buffalo School of Law. For more information, please contact [email protected]. The Voyage of the Neptune Jade: The Perils and Promises of Transnational Labor Solidarity JAMES ATLESONt An injury to one is an injury to all.' If you're not part of the solution, you're part of the problem. Sympathy strikes.., are becoming increasingly frequent because of the move towards the concentration of enterprises, the globalization of the economy and the delocalization of work centers. While pointing out that a number of distinctions need to be drawn here,. .. the [ILO Freedom of Association] Committee considers that a general prohibition on sympathy strikes could that workers should be able to take such action,2 lead to abuse and is itself lawful.