Title Multiculturalism: a Study of Plurality and Solidarity in Colonial

Total Page:16

File Type:pdf, Size:1020Kb

Load more

Recommended publications

-

Begin Your Joyous Spring with Bosch. Embrace the Season with the Best Help for Your Home

Begin your joyous spring with Bosch. Embrace the season with the best help for your home. The Bosch CNY Home Prep Guide Promotion period: 3rd January – 28th February 2018 www.bosch-home.com.sg/springofjoy THE BOSCH CNY HOME PREP GUIDE The perfect way to welcome the new Year of the Dog. Use this CNY planning calendar for a smooth and happy new year. JANUARY 1 WEEK BEFORE (1st to 31st Jan) (8th to 14th Feb) Good idea to visit the Spring Cleaning Find, buy and Shop for snacks, Shop for Reunion bank and prepare your (traditionally on wash New drinks, flowers Menu (and red packets 24th day or 9 Feb) Clothes and oranges Yu Sheng) CHINESE NEW YEAR DAY CNY EVE (16th Feb) (15th Feb) CNY Greetings Give lucky Welcome Guests Put up those Reunion “守岁” - Stay to everyone Red Packets to your home couplets and Dinner with awake to extend you meet to children ornaments your loved your parents’ ones longevity CNY DAY 2 – 7 CNY DAY 15 元宵节 (17th to 22nd Feb) (2nd Mar) Visit your relatives Everyone’s Birthday Celebrate the Enjoy 汤圆, or and friends or “人日”on 22 Feb Lantern Festival Sweet Dumplings THE BOSCH CNY HOME PREP GUIDE Freshening your home for a Prosperous New Year. Chinese New Year is a great time to usher out the old to make room for the new – starting with things at home! COOK up a feast WASH away the bad Use Bosch kitchen machines and food processors to Washing machines and dryers are prepare your feasts easily with professional results. -

The Decade Ahead

Issue 03 1 Positivity wins The Decade Ahead It's official: basic Stewards of classic Linking up with kindred Ponies got talent! bubbles are back! cocktails for the spirits beyond the Celebrating diversity generations to come industry in our team 2020 A Jigger & Pony Publication $18.00 + GST 56 2 3 Gin & Sonic Monkey 47 Gin, soda water, tonic water, grapefruit juice 25 per cocktail Prices subject to 10% service charge and 7% GST 4 5 Contents pg. Basic bubbles are back 10 Stripped down cocktails that are deceptively simple Principal Footloose and fancy fizz 16 Celebrating humankind’s fascination with things that go ‘pop’ bartender’s A sense of place 20 Embracing flavours that evoke welcome a sense of place across Asia Kindred spirits 22 Meet team Fossa, local craft chocolate makers with a passion Positivity wins! for creating new flavours Collaboration across borders 26 My bartending journey started eight years ago, around the same time that Jigger A collaboration between bartenders from & Pony was opening its doors for the first time. That was also the beginning of a opposite ends of the globe cocktail revolution that would shape the drinks world as we know it today. The boundaries of cocktail-making have been pushed to places we could never have imagined, and customer knowledge of product and drinks is stronger than ever. Passing down the 28 tradition of classics When we first started designing this menu-zine, the team reviewed the trends and Stewards of classic cocktails for stories of the past decade, and what we’ve seen is that sheer passion (and a healthy generations to come dose of positivity) can spread and influence the way people choose to enjoy the important moments of their lives. -

Menu Order Form

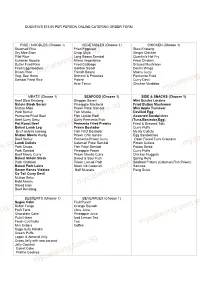

QUENTIN'S $15.00 PER PERSON ONLINE CATERING ORDER FORM RICE / NOODLES (Choose 1) VEGETABLES (Choose 1) CHICKEN (Choose 1) Steamed Rice Fried Eggplant Stew Kristang Dry Mee Siam Chap Chye Ginger Chicken Pilaf Rice Long Beans Sambal Quentin's Hot Fry Eurasian Noodle Mixed Vegetables Fried Chicken Butter Fried Rice Fried Cabbage Braised Mushroom Fried Egg Noodles Garden Salad Devil's Wings Bryani Rice French Beans Moeru Curry Veg. Bee Hoon Broccoli & Potatoes Permenta Fried Sambal Fried Rice Patchri Curry Devil Acar Timun Chicken Vindaloo MEATS (Choose 1) SEAFOOD (Choose 1) SIDE & SNACKS (Choose 1) Beef Stew Kristang Singgan Serani Mini Quiche Loraine Sirloin Steak Serani Pineapple Mackeral Fried Button Mushroom Mutton Miso Prawn Petai Sambal Mini Apple Turnover mycatering.com.sg Pork Semur mycatering.com.sg Fish Moolie Devilled Egg Permenta Fried Beef Fish Lemak Padi Assorted Sandwiches Beef Curry Seku Curry Permenta Fish (Tuna,Bostador,Egg) Pot Roast Beef Permenta Fried Prawns Fried & Dressed Tofu Baked Lamb Leg Prawn Bostador Curry Puffs Beef ambilla kacang Fish Fillet Bostador Meaty Cutlets Mutton Moeru Curry Prawn Chili Garam Egg Sandwiches Beef Semur Permenta Prawn Curry Open Faced Tuna Croutons Lamb Cutlets Calamari Petai Sambal Potato Cutlets Pork Chops Fish Petai Sambal Potato Salad Pork Sambal Pineapple Prawn Curry Puffs Beef Moeru Curry Prawn Moolie Curry Chicken Nuggets Baked Sirloin Steak Sweet & Sour Fish Spring Rolls Pork Vindaloo Prawn Lemak Padi Seafood Fritters (Calamari,Fish,Prawn) mycatering.com.sg Baked Pork Loins mycatering.com.sg -

Chinese New Year Eve, Day 1 & 2

Chinese New Year Eve, Day 1 & 2 Dinner Buffet Menu 11 Feb to 13 Feb 2021 $138++ per adult $25++ per child (6 to 12 years old) Offer: 50% off for Adults Appetizers Salmon Sushi and Cucumber Maki Salmon Sashimi Seafood with Selection of Condiments (Prawn, Mussel, Clam, Scallop, Baby Lobster [1pc each] and French Oyster [6pc per serving] with Lemon and Dipping Sauce) Bouquet of Green Leaves Mesclun, Romaine Lettuce, Rocket Cherry Tomato, Japanese Cucumber, Carrot, Red Radish, Sweet Corn, Crouton, Parmesan Cheese with Caesar Dressing, Thousand Island, Italian Dressing and Herbs Olive Oil Compound Salad Chicken (Szechuan Style) Spicy Glass Noodle with Seafood Salad Roast Duck Salad with Lychee Chicken Bak Kwa Western Salad Tabbouleh Salad Greek Salad Duo Mushroom Salad Quinoa with Pumpkin, Kale, Cranberries and Pine Nuts Kindly note that this menu is subject to changes on a daily basis depending on the availability of dishes and their ingredients. 317 Outram Road, Level 4, Singapore 169075 +65 3138 2530 [email protected] singaporeatrium.holidayinn.com facebook.com/hiatrium @holidayinnsgatrium Soup Crabmeat and Fish Maw Soup Asian Delight Beef Rendang Chilli Crab with Mantou Braised Sea Cucumber with Chicken and Mushroom Wok-fried Chicken with Ginger and Fruit sauce Hong Kong-style Fried Fish Fillet Crabmeat and Egg White Fried Rice Steamed Vegetables with Dried Oyster and Fatt Choy Western Seafood Thermidor Roast Lamb Leg with Rosemary Jus Roast Spring Chicken with Tapenade Sauce Roasted Vegetables with Herbs Roast Potato and Vine Tomato Confit Indian Chaffer Kadai Prawn Butter Chicken Aloo Gobi Basmati Rice with Mutton Kindly note that this menu is subject to changes on a daily basis depending on the availability of dishes and their ingredients. -

Wedding Bbq Buffet Menu Copy

MENU SELECTION FOR BBQ & BUFFET MENU SELECTION FOR bbq & buffet YOUR CHOICE OF DINNER ( Starter & soup are served, main course as buffet deluxe BBQ style. Please select menu from below list ) starter & Soup ( PLEASE SELECT 1 +1 SOUP ) E1 sUSHI & SASHIMI, MARKET FISH SELECTION, PICKLED GINGER, WASABI AND SOYA SAUCE E2 SMOKED SALMON, SOURDOUGH TOAST, MAYONNAISE, WILD ROCKET SALAD E3 TIGER PRAWNS COCKTAIL BELUGA CAVIAR STRAWBERRY SALSA, AVOCADO, MIXED LEAVES, MANGO DRESSING GARLIC BREAD E4 AYAM PELALAH, GRILLED SHREDDED CHICKEN SALAD MIXED WITH SAMBAL BAJAK AND SAMBAL MATAH E5 BAY-SMOKED MAHI MAHI, ASPARAGUS, CHERRY TOMATO, KALAMATA OLIVE E6 ASSORTED BRUSCETTA E7 POACHED LOBSTER COCKTAIL, LETTUCE, MANGO AND STRAWBERRY SALSA, AVOCADO E8 CAESAR SALAD (ACTION) BABY GEM LETTUCE, SMOKED BACON, PARMESAN, QUAL EGG ANCHOVIES, CROUTON E9 VIETNAMESE SPRING ROLLS FILLED WITH LOBSTER & PRAWN, SESAME SOY DIP E10 GUACAMOLE (ACTION) SERVED WITH NACHOS E11 LARB GAI SPICED MINCED CHICKEN AND ROMAINE LETTUCE SALAD E12 GREEN PAPAYA, MANGO, CHILLI, COCONUT, PALM SUGAR DRESSING E13 THAI BEEF SALAD, CHILLI, CORIANDER, GREEN PAPAYA E14 MIXED WILD BEANS, FETA, CORIANDER, SUNDRIED TOMATO, OLIVE OIL, LIME JUICE E15 DRESSED CRAB CHIVES & SMOKED SALMON, SOURDOUGH TOAST, MAYONNAISE, WILD ROCKET SALAD E16 TOM YAM GOONG, HOT AND SOUR, PRAWN, MUSHROOMS, CORIANDER E17 ROASTED PUMPKIN AND GINGER CORIANDER, HONEY, CINNAMON E18 SOP BUNTUT, INDONESIAN OXTAIL SOUP E19 HAM AND SPLIT PEA OREGANO, YOGURT, MINT E20 MINESTRONE WITH PASTA, BACON AND ROOT VEGETABLE BRUNOISE E21 CREAM OF CHICKEN AND SWEETCORN WITH ROASTED GARLIC CRISPS E22 BEEF CONSOMME WITH ROOT VEGETABLE PEARLS E23 MUSHROOM CAPPUCINO, TRUFFLE OIL E24 CHINESE STYLE CRAB, SWEETCORN, ASPARAGUS, EGG E25 LOBSTER BISQUE, ROUILLE, CROUTONS E26 GRADE *AAA* TUNA TARTARE COCKTAIL PICKLED CUCUMBER, MANGO, AVOCADO, WASABI gARLIC BREAD ON ICE E27 SZECHUAN HOT AND SOUR SOUP E28 TOMATO, BOCCONCINI, PINE NUTS, GREEN PESTO E29 NATIVE LIVE OYSTERS. -

Singapore Dishes TABLE of CONTENTS

RECIPE BOOKLET ERIC M A’ A S C O D O N K A E R B R Singapore Dishes TABLE OF CONTENTS COOKING WITH PRESSURE ................................................. 3 VENTING METHODS ................................................................ 4 INSTANT POT FUNCTIONS COOKING TIME ................... 5 MAINS HAINANESE CHICKEN RICE .................................................. 6 STEAMED SHRIMP GLASS VERMICELLI .......................... 8 MUSHROOM & SCALLOP RISOTTO ................................... 10 CHICKEN VEGGIE MAC AND CHEESE............................... 12 HAINANESE HERBAL MUTTON SOUP.............................. 14 STICKY RICE DUMPLINGS ..................................................... 16 CURRY CHICKEN ....................................................................... 18 TEOCHEW BRAISED DUCK ................................................... 19 CHICKEN CENTURY EGG CONGEE .................................... 21 DESSERTS PULOT HITAM ............................................................................ 22 STEAMED SUGEE CAKE ........................................................ 23 PANDAN CAKE........................................................................... 25 Cooking with Pressure FAST The contents of the pressure cooker cooks at a higher temperature than what can be achieved by a conventional Add boil — more heat means more speed. ingredients Pressure cooking is about twice as fast as conventional cooking (sometimes, faster!) & liquid to Instant Pot® HEALTHY Pressure cooking is one of the healthiest -

C a N D L E N

COMODEMPSEY.SG C A N D L E N U T 1800 304 2288 [email protected] The world’s first Michelin-starred Peranakan restaurant, Candlenut takes a contemporary yet authentic approach to traditional Straits-Chinese cuisine. The restaurant serves up refined Peranakan cuisine that preserves the essence and complexities of traditional food, with astute twists that lift the often rich dishes to a different level. Executive Head Chef and Owner, Malcolm Lee’s degustation menus are carefully crafted on a frequent basis, ensuring a new and exciting culinary experience each time. A B O U T Malcolm Lee Executive Head Chef and owner, Malcolm Lee’s passion in cooking was sparked by his mother and grandmother. He started Candlenut at a young age of 25 striving to create refined and inspired Peranakan dishes reminiscent of the yesteryears. Chef Malcolm commits to using only the freshest seasonal produce available, without comprising on taste of quality. Today, Candlenut is internationally recognised as the world’s first and only Michelin starred restaurant serving local Singapore flavours and favourites. Chef Malcolm himself, alongside his talented kitchen and front of house team, are more than happy to work with you to customize any individual or communal style dining packages for your event. P R I V A T E E V E N T For a group of up to a maximum of 90 guests our restaurant is perfect! The Venue offers a private lawn giving guests a unique yet casual space for Canapés and Drinks. D E T A I L S MINIMUM SPEND LUNCH DINNER 12 PM – 3.30 PM 6 PM – 10.30 PM Monday-Thursday S$ 8,000++ S$ 12,000++ Friday- Sunday & S$ 10,000++ S$ 15,000++ Public Holiday CAPACITY Sit down event: Up to 90 guests, inclusive of private dining room for 10 guests. -

Large Plates Desserts Sides Small Plates Burgers

dinner menu monday to sunday 5.30pm to 9pm small plates burgers SOUP OF THE DAY GADO GADO BOATS Ask your server for today’s flavour, Satay tofu with roasted red pepper, with toasted bread (v, gf) $12 peanut crumble & avocado in baby ROYALE WITH CHEESE gem lettuce (v, gf) $13 Double seitan ‘meat’ patty, burger HOUSEBAKED BREAD sauce, pickles, vegan cheese, Sourdough focaccia with olive oil NASHVILLE CAULI lettuce & tomato, with fries (v, nf) (v, nf,) $6 Spicy, battered cauliflower bites $22 with ranch sauce (v, gf, nf) $11 OLIVES ‘CHICKEN’ TIKKA Marinated Sicilian & Kalamata olives BRUSCHETTA Sunfed ‘chicken’ tikka spiced patty, & sun-dried tomato (v, gf, af, nf) $8 Roasted red pepper, olive, artichoke, with coconut yoghurt, lettuce, pickled onion & sun-dried tomato red onion, red pepper, mustard, HERB SALTED FRIES cream cheese on grilled housemade gherkins & aioli, with fries (v, gf*, nf) Fries with aioli (v, gf, nf) $9 sourdough focaccia (v, gf*) $14 $22 LOADED FRIES GARDEN SALAD THE BFC: BOTANIST FRIED CHEESE Fries with gravy, jalapeños, Angel Rocket, baby spinach, pickled red Crumbed halloumi, smoky BBQ Food feta & crispy shallots onion, puffed quinoa, sun-dried sauce, housemade facon, smoked (v, gf*, nf) $13 tomato & coconut yoghurt dressing cheddar, red cabbage & carrot slaw, JALAPEÑO POPPERS (v, gf, nf) $9 with fries (nf) $22 Stuffed with cashew ricotta, with ranch sauce (v, gf) $13 sides taco tuesday! tacos & a pint $20 every tuesday 5.30 to 9pm PAN-FRIED GREENS Seasonal greens with house roasted peanuts (v, gf) $8 CRUSHED BABY -

DARI DAPUR BONDA Menu Ramadan 2018

DARI DAPUR BONDA Menu Ramadan 2018 MENU 1 Pak Ngah - Ulam-Ulaman Pucuk Paku, Ubi, Ulam Raja, Ceylon, Pegaga, Timun, Tomato, Kubis, Terung, Jantung Pisang, Kacang Panjang and Kacang Botol Sambal-Sambal Melayu Sambal Belacan, Tempoyak, Cili Kicap, Budu, Cencaluk, Air Asam, Tomato Sauce, Chili Sauce, Sambal Cili Hijau, Sambal Cili Merah, Sambal Nenas, Sambal Manga Pak Andak – Pembuka Selera Gado-Gado Dengan Kuah Kacang / Rojak Pasembur Kerabu Pucuk Paku, Kerabu Daging Salai Bakar Kerabu Manga Ikan Bilis Acar Buah Telur Masin, Ikan Masin, Tenggiri, Sepat, Gelama Dan Pari Keropok Keropok Ikan, Keropok Udang, Keropok Sotong, Keropok Malinjo, Keropok Sayur & Papadom Pak Cik- Salad Bar Assorted Garden Green Lettuce with Dressing and Condiments German Potato Salad, Coleslaw & Tuna Pasta Assorted Cheese, Crackers, Dried Fruit and Nuts Pak Usu – Segar dari Lautan Prawn, Bamboo Clam, Green Mussel & Oyster Lemon Wedges, Tabasco, Plum Sauce & Goma Sauce Jajahan Dari Timur - Japanese - Action Stall Assorted Sushi, Maki Roll & Sashimi - Maguro, Salmon Trout & Octopus Pickle Ginger, Shoyu, Wasabi Jajahan Dari Timur -Teppanyaki Prawn & Chicken with Vegetables Pak Ateh -Soup Sup Tulang Rusuk Cream of Pumkin Soup Assorted Bread & Butter Ah Seng - Itik & Ayam - Action Stall Ayam Panggang & Itik Panggang Nasi Ayam & Sup Ayam Chili, Kicap, Halia & Timun Mak Usu - Noodles Counter -Action Stall Mee Rebus, Clear Chicken Soup & Nonya Curry Laksa Dim Sum Assorted Dim Sum with Hoisin Sauce, Sweet Chilli & Thai Chilli Pak Uda - Ikan Bakar- Action Stall Ikan Pari, Ikan -

Carbohydrate Counting List

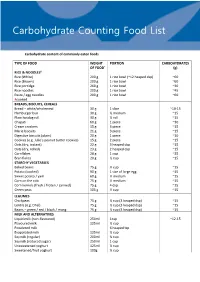

Tr45 Carbohydrate Counting Food List Carbohydrate content of commonly eaten foods TYPE OF FOOD WEIGHT PORTION CARBOHYDRATES OF FOOD* (g) RICE & NOODLES# Rice (White) 200 g 1 rice bowl (~12 heaped dsp) ~60 Rice (Brown) 200 g 1 rice bowl ~60 Rice porridge 260 g 1 rice bowl ~30 Rice noodles 200 g 1 rice bowl ~45 Pasta / egg noodles 200 g 1 rice bowl ~60 #cooked BREADS, BISCUITS, CEREALS Bread – white/wholemeal 30 g 1 slice ~10-15 Hamburger bun 30 g ½ medium ~15 Plain hotdog roll 30 g ½ roll ~15 Chapati 60 g 1 piece ~30 Cream crackers 15 g 3 piece ~15 Marie biscuits 21 g 3 piece ~15 Digestive biscuits (plain) 20 g 1 piece ~10 Cookies (e.g. Julie’s peanut butter cookies) 15 g 2 piece ~15 Oats (dry, instant) 22 g 3 heaped dsp ~15 Oats (dry, rolled) 23 g 2 heaped dsp ~15 Cornflakes 28 g 1 cup ~25 Bran flakes 20 g ½ cup ~15 STARCHY VEGETABLES Baked beans 75 g ⅓ cup ~15 Potato (cooked) 90 g 1 size of large egg ~15 Sweet potato / yam 60 g ½ medium ~15 Corn on the cob 75 g ½ medium ~15 Corn kernels (fresh / frozen / canned) 75 g 4 dsp ~15 Green peas 105 g ½ cup ~15 LEGUMES Chickpeas 75 g ½ cup (3 heaped dsp) ~15 Lentils (e.g. Dhal) 75 g ½ cup (3 heaped dsp) ~15 Beans – green / red / black / mung 75 g ½ cup (3 heaped dsp) ~15 MILK AND ALTERNATIVES Liquid milk (non-flavoured) 250ml 1cup ~12-15 Flavoured milk 125ml ½ cup Powdered milk 6 heaped tsp Evaporated milk 125ml ½ cup Soymilk (regular) 200ml ¾ cup Soymilk (reduced sugar) 250ml 1 cup Unsweetened yoghurt 125ml ½ cup Sweetened/fruit yoghurt 100g ⅓ cup TYPE OF FOOD WEIGHT PORTION CARBOHYDRATES OF -

C a N D L E N U T Circuit Breaker Menu

C A N D L E N U T Circuit Breaker Menu STARTERS Bakwan Kepiting Soup $20 Blue Swimmer crab chicken balls, bamboo shoot, rich chicken broth boiled over 4 hours – Individual Portion Ngoh Hiang $20 Minced pork, prawns, shiitake mushroom, water chestnut wrapped in crispy deep fried beancurd skin Snake River Farm Kurobuta Pork Neck Satay $20 Glazed with kicap manis, grilled and smoked over charcoal – 4 skewers CURRIES & BRAISES Chap Chye $20 Cabbage, black mushroom, pork belly, lily buds, black fungus, vermicelli braised in rich prawn stock Chef’s Mum’s Chicken Curry $20 A signature dish of my mother, a must have dish at every family special occasion, Toh Thye San Chicken cooked with potato, kaffir lime leaf Westholme Wagyu Beef Rib Rendang $20 Dry caramelised curry cooked over 4 hours with spices and turmeric leaf garnished with Serunding Aunt Caroline’s Babi Buah Keluak $20 Slow cooked Free- range Borrowdale Pork soft bone with an aromatic and intense “poisonous” black nut gravy Blue Swimmer Crab Curry $20 A Candlenut signature, turmeric, galangal, kaffir lime leaf Babi Pongteh $20 Slow braised Borrowdale free range pork belly, shitake mushrooms, preserved soy bean paste, spoon cut chilli Ikan Assam Pedas $20 Kühlbarra ocean barramundi fillet cooked in a spicy tangy gravy with baby okra, brinjal and honey pineapple Ikan Chuan Chuan $20 Local red lion snapper fillet fried and coated in an aromatic fermented soy bean and ginger sauce, fried ginger strips CHINESE WOK Chincalok Omelette $20 House fermented baby shrimp, also known as grago, Freedom range co. eggs, spring onion, crab meat Candlenut’s Buah Keluak Fried Rice $20 Fried with rich Indonesian black nut sambal, Freedom range co. -

Corporate Events

TO ORDER, CONTACT +65 6235 6275 | 2 CORPORATE MENU CORPORATE CORPORATE MENU 1 STARTERS (WESTERN) STARTERS (ASIAN) LUNCH (MIN. 20 PAX) • House-Smoked Ocean Trout with Fresh Wasabi Dressing • Dutch-Style Chicken & Vegetable Rissoles Lunch Buffet - $48+ Per Pax • ‘Gado-Gado’ Indonesian Salad of Mixed Vegetables Premium Lunch Buffet - $60+ Per Pax • Antipasto of Char-Grilled Mediterranean Vegetables with Egg, Potato & Peanut Dressing Service Staff - $100+ Per Staff Catering Fees - $15+ Per Pax • Roma Tomato & Bocconcini Salad with Basil, • ‘Tahu Telur’ Crispy Tofu Omelette with Aged Balsamic & Extra Virgin Olive Oil Vegetable Julienne & Peanut Dressing Starters - Select 3 Mains - Select4 • Char-Grilled Portobello & Forrest Mushroom with Garlic • Thai Glass Vermicelli Salad with Chilli-Lime Dressing, Sides - Select 2 Herb & Aged Balsamic Dried Shrimp, Minced Meat & Cashew Nuts Dessert - Select 1 • Seafood Pasta Salad with Thousand Island Dressing • ‘Lemper’ Glutinous with Lemongrass Chicken • Caesar Salad with Parmesan, Eggs, Croutons & Bacon • Chilled Cha-Soba with Oriental Mushrooms 2 & Truffle Soy Dressing • Niçoise Salad with Egg, Tuna, Potatoes, Onions, DINNER (MIN. 20 PAX) Olives, Tomatoes • Manado’ Seafood Ceviche with Coconut Milk, Lemon Basil, Chilli & Lime Dinner Buffet - $68+ Per Pax • House-Smoked Ocean Trout with Caviar Crème Fraiche Premium Dinner Buffet - $80+ Per Pax Duck Rillette with Cornichons Service Staff - $100+ Per Staff TO ORDER, CONTACT +65 6235 6275 | 3 ORDER, 6275 TO 6235 +65 CONTACT Catering Fees - $15+ Per Pax • Salad of Confit Salmon, Grilled Asparagus, Baby Spinach & Yuzu Dressing Starters - Select 3 • Char-Grilled Spanish Octopus Salad, Mains - Select 6 Lemon-Garlic Dressing Sides - Select 2 Dessert - Select 1 + Fruit Platter *Catering fees include transport, set-up, tear down & tableware CORPORATE MENU 1 MAINS (WESTERN) LUNCH (MIN.