The Church, Consanguinity and Trollope

Total Page:16

File Type:pdf, Size:1020Kb

Load more

Recommended publications

-

The Origins and Consequences of Kin Networks and Marriage Practices

The origins and consequences of kin networks and marriage practices by Duman Bahramirad M.Sc., University of Tehran, 2007 B.Sc., University of Tehran, 2005 Thesis Submitted in Partial Fulfillment of the Requirements for the Degree of Doctor of Philosophy in the Department of Economics Faculty of Arts and Social Sciences c Duman Bahramirad 2018 SIMON FRASER UNIVERSITY Summer 2018 Copyright in this work rests with the author. Please ensure that any reproduction or re-use is done in accordance with the relevant national copyright legislation. Approval Name: Duman Bahramirad Degree: Doctor of Philosophy (Economics) Title: The origins and consequences of kin networks and marriage practices Examining Committee: Chair: Nicolas Schmitt Professor Gregory K. Dow Senior Supervisor Professor Alexander K. Karaivanov Supervisor Professor Erik O. Kimbrough Supervisor Associate Professor Argyros School of Business and Economics Chapman University Simon D. Woodcock Supervisor Associate Professor Chris Bidner Internal Examiner Associate Professor Siwan Anderson External Examiner Professor Vancouver School of Economics University of British Columbia Date Defended: July 31, 2018 ii Ethics Statement iii iii Abstract In the first chapter, I investigate a potential channel to explain the heterogeneity of kin networks across societies. I argue and test the hypothesis that female inheritance has historically had a posi- tive effect on in-marriage and a negative effect on female premarital relations and economic partic- ipation. In the second chapter, my co-authors and I provide evidence on the positive association of in-marriage and corruption. We also test the effect of family ties on nepotism in a bribery experi- ment. The third chapter presents my second joint paper on the consequences of kin networks. -

Change in the Prevalence and Determinants of Consanguineous Marriages in India Between National Family and Health Surveys (NFHS) 1 (1992–1993) and 4 (2015–2016)

Wayne State University Human Biology Open Access Pre-Prints WSU Press 11-10-2020 Change in the Prevalence and Determinants of Consanguineous Marriages in India between National Family and Health Surveys (NFHS) 1 (1992–1993) and 4 (2015–2016) Mir Azad Kalam Narasinha Dutt College, Howrah, India Santosh Kumar Sharma International Institute of Population Sciences Saswata Ghosh Institute of Development Studies Kolkata (IDSK) Subho Roy University of Calcutta Follow this and additional works at: https://digitalcommons.wayne.edu/humbiol_preprints Recommended Citation Kalam, Mir Azad; Sharma, Santosh Kumar; Ghosh, Saswata; and Roy, Subho, "Change in the Prevalence and Determinants of Consanguineous Marriages in India between National Family and Health Surveys (NFHS) 1 (1992–1993) and 4 (2015–2016)" (2020). Human Biology Open Access Pre-Prints. 178. https://digitalcommons.wayne.edu/humbiol_preprints/178 This Article is brought to you for free and open access by the WSU Press at DigitalCommons@WayneState. It has been accepted for inclusion in Human Biology Open Access Pre-Prints by an authorized administrator of DigitalCommons@WayneState. Change in the Prevalence and Determinants of Consanguineous Marriages in India between National Family and Health Surveys (NFHS) 1 (1992–1993) and 4 (2015–2016) Mir Azad Kalam,1* Santosh Kumar Sharma,2 Saswata Ghosh,3 and Subho Roy4 1Narasinha Dutt College, Howrah, India. 2International Institute of Population Sciences, Mumbai, India. 3Institute of Development Studies Kolkata (IDSK), Kolkata, India. 4Department of Anthropology, University of Calcutta, Kolkata, India. *Correspondence to: Mir Azad Kalam, Narasinha Dutt College, 129 Belilious Road, West Bengal, Howrah 711101, India. E-mail: [email protected]. Short Title: Change in Prevalence and Determinants of Consanguineous Marriages in India KEY WORDS: NATIONAL FAMILY AND HEALTH SURVEY, CONSANGUINEOUS MARRIAGE, DETERMINANTS, RELIGION, INDIA. -

Texas Nepotism Laws Made Easy

Texas Nepotism Laws Made Easy 2016 Editor Zindia Thomas Assistant General Counsel Texas Municipal League www.tml.org Updated July 2016 Table of Contents 1. What is nepotism? .................................................................................................................... 1 2. What types of local government officials are subject to the nepotism laws? .......................... 1 3. What types of actions are generally prohibited under the nepotism law? ............................... 1 4. What relatives of a public official are covered by the statutory limitations on relationships by consanguinity (blood)? .................................................................................. 1 5. What relationships by affinity (marriage) are covered by the statutory limitations? .............. 2 6. What happens if it takes two marriages to establish the relationship with the public official? ......................................................................................................................... 3 7. What actions must a public official take if he or she has a nepotism conflict? ....................... 3 8. Do the nepotism laws apply to cities with a population of less than 200? .............................. 3 9. May a close relative be appointed to an unpaid position? ....................................................... 3 10. May other members of a governing body vote to hire a person who is a close relative of a public official if the official with the nepotism conflict abstains from deliberating and/or -

Stages of Papal Law

Journal of the British Academy, 5, 37–59. DOI https://doi.org/10.5871/jba/005.037 Posted 00 March 2017. © The British Academy 2017 Stages of papal law Raleigh Lecture on History read 1 November 2016 DAVID L. D’AVRAY Fellow of the British Academy Abstract: Papal law is known from the late 4th century (Siricius). There was demand for decretals and they were collected in private collections from the 5th century on. Charlemagne’s Admonitio generalis made papal legislation even better known and the Pseudo-Isidorian collections brought genuine decretals also to the wide audience that these partly forged collections reached. The papal reforms from the 11th century on gave rise to a new burst of papal decretals, and collections of them, culminating in the Liber Extra of 1234. The Council of Trent opened a new phase. The ‘Congregation of the Council’, set up to apply Trent’s non-dogmatic decrees, became a new source of papal law. Finally, in 1917, nearly a millennium and a half of papal law was codified by Cardinal Gasparri within two covers. Papal law was to a great extent ‘demand- driven’, which requires explanation. The theory proposed here is that Catholic Christianity was composed of a multitude of subsystems, not planned centrally and each with an evolving life of its own. Subsystems frequently interfered with the life of other subsystems, creating new entanglements. This constantly renewed complexity had the function (though not the purpose) of creating and recreating demand for papal law to sort out the entanglements between subsystems. For various reasons other religious systems have not generated the same demand: because the state plays a ‘papal’ role, or because the units are small, discrete and simple, or thanks to a clear simple blueprint, or because of conservatism combined with a tolerance of some inconsistency. -

Cousin Marriage & Inbreeding Depression

Evidence of Inbreeding Depression: Saudi Arabia Saudi Intermarriages Have Genetic Costs [Important note from Raymond Hames (your instructor). Cousin marriage in the United States is not as risky compared to cousin marriage in Saudi Arabia and elsewhere where there is a long history of repeated inter-marriage between close kin. Ordinary cousins without a history previous intermarriage are related to one another by 0.0125. However, in societies with a long history of intermarriage, relatedness is much higher. For US marriages a study published in The Journal of Genetic Counseling in 2002 said that the risk of serious genetic defects like spina bifida and cystic fibrosis in the children of first cousins indeed exists but that it is rather small, 1.7 to 2.8 percentage points higher than for children of unrelated parents, who face a 3 to 4 percent risk — or about the equivalent of that in children of women giving birth in their early 40s. The study also said the risk of mortality for children of first cousins was 4.4 percentage points higher.] By Howard Schneider Washington Post Foreign Service Sunday, January 16, 2000; Page A01 RIYADH, Saudi Arabia-In the centuries that this country's tribes have scratched a life from the Arabian Peninsula, the rule of thumb for choosing a marriage partner has been simple: Keep it in the family, a cousin if possible, or at least a tribal kin who could help conserve resources and contribute to the clan's support and defense. But just as that method of matchmaking served a purpose over the generations, providing insurance against a social or financial mismatch, so has it exacted a cost--the spread of genetic disease. -

Legislating First Cousin Marriage in the Progressive Era

KISSING COUSINS: LEGISLATING FIRST COUSIN MARRIAGE IN THE PROGRESSIVE ERA Lori Jean Wilson Consanguineous or close-kin marriages are older than history itself. They appear in the religious texts and civil records of the earliest known societies, both nomadic and sedentary. Examples of historical cousin-marriages abound. However, one should not assume that consanguineous partnerships are archaic or products of a bygone era. In fact, Dr. Alan H. Bittles, a geneticist who has studied the history of cousin-marriage legislation, reported to the New York Times in 2009 that first-cousin marriages alone account for 10 percent of global marriages.1 As of 2010, twenty-six states in the United States permit first cousin marriage. Despite this legal acceptance, the stigma attached to first-cousin marriage persists. Prior to the mid- nineteenth century, however, the American public showed little distaste toward the practice of first cousin marriage. A shift in scientific opinion emerged in the mid-nineteenth century and had anthropologists questioning whether the custom had a place in western civilization or if it represented a throwback to barbarism. The significant shift in public opinion however, occurred during the Progressive Era as the discussion centered on genetics and eugenics. The American public vigorously debated whether such unions were harmful or beneficial to the children produced by first cousin unions. The public also debated what role individual states, through legislation, should take in restricting the practice of consanguineous marriages. While divergent opinions emerged regarding the effects of first cousin marriage, the creation of healthy children and a better, stronger future generation of Americans remained the primary goal of Americans on both sides of the debate. -

Politics and Marriage in South Kamen (Chad)

POLITICS AND MARRIAGE IN SOUTH KANEM (CHAD) : A STATISTICAL PRESENTATION OF ENDOGAMY FROM 1895 TO 1975 Edouard CONTE SYST~ES MATRIMONIAUX AU SUD KANEM (TCHAD): PRÉSENTATION STATISTIQUE DE L'ENDOGAMIE DE 18% b 1975 Le but du prkwzt article est de faire connaître les résrdiuts préliminuiws d’une étude de l’endogamie et de l’organisation lignagère menée sur une base comparative aupr& des deux principales strates sociales renconirées chez les populations kanambti des rives nord-est du Lac Tchad. Le mot kanambti peut dèsigtzer toute personne originaire du Kattem ef dottf la langne maternelle est le lranambukanambti. Toutefois, dans l’usage courant, cetie dèt~ntnittatiot~ est rèserv& nus ligttages donf les prétentions généalogiques remontent aux Sefarva ou à leurs successeurs ou alliés entre qui le mariage est irnditior~nellernet~~ licite. Partni les hommes libres, on distiilgue, cependant, les (<gens de la lance j> ou h’anemborr se considtirant Q nobles jj au sens le plus large et les + gens de l’arc b, mieux connus SOLLS l’appellation de HerltlSc1 que nous rapporttkent dèjà les erplorateurs allemands BARTH et NACHTIGAL. Ce tertne signifie forgeron en arabe mais les Kanembou opèrent une distinction entre les artisans forgerons (kzig&nà) et les membres d’un lignaye dit ’ forgeron ’ ((II?). Les Haddad reprèsentenf environ 20 :/o de la population kanem bou muis cefte proporliotl subif de larges variations d’un endrolb ti l’autre. Le choix de leurs lieue de résidence est largement fonctiotl des exigences économiques de leurs maîtres ainsi que du degré d’autonomie politique qu’ils oni su conquérir. -

MANUAL of POLICY Title Nepotism: Public Officials 1512 Legal

MANUAL OF POLICY Title Nepotism: Public Officials 1512 Legal Authority Approval of the Board of Trustees Page 1 of 2 Date Approved by Board Board Minute Order dated November 26, 2019 I. Purpose The purpose of this policy is to provide provisions regarding nepotism prohibition of public officials as defined by the consanguinity and affinity relationship. II. Policy A. Nepotism Prohibitions Applicable to Public Officials As public officials, the members of the Board of Trustees and the College President are subject to the nepotism prohibitions of Chapter 573 of the Texas Government Code. South Texas College shall not employ any person related within the second degree by affinity (marriage) or within the third degree by consanguinity (blood) to any member of the Board or the College President when the salary, fees, or compensation of the employee is paid from public funds or fees of office. A nepotism prohibition is not applicable to the employment of an individual with the College if: 1) the individual is employed in the position immediately before the election or appointment of the public official to whom the individual is related in a prohibited degree; and 2) that prior employment of the individual is continuous for at least: a. 30 days, if the public official is appointed; b. six months, if the public official is elected at an election other than the general election for state and county officers; or c. one year, if the public official is elected at the general election for state and county officers. If an individual whose employment is not subject to the nepotism prohibition continues in a position, the College President or the member of the Board of Trustees to whom the individual is related in a prohibited degree may not participate in any deliberation or voting on the employment, reemployment, change in status, compensation, or dismissal of the individual if that action applies only to the individual and is not taken regarding a bona fide class or category of employees. -

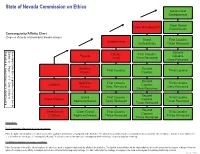

Third Degree of Consanguinity

State of Nevada Commission on Ethics Great-Great Grandparents 4 Great Grand Great Grandparents Uncles/Aunts Consanguinity/Affinity Chart 3 5 (Degrees of family relationship by blood/marriage) Grand First Cousins Grandparents Uncles/Aunts Twice Removed 2 4 6 Second Uncles First Cousins Parents Cousins Aunts Once Removed 1 3 5 Once Removed 7 Brothers Second First Cousins Third Cousins Sisters Cousins 2 4 6 8 Second Nephews First Cousins Third Cousins Children Cousins Nieces Once Removed Once Removed 1 3 5 Once Removed 7 9 Second Grand First Cousins Third Cousins Grand Children Cousins Nephews/Nieces Twice Removed Twice Removed 1 2 4 6 Twice Removed 8 0 Second Great Grand Great Grand First Cousins Third Cousins Cousins Children Nephews/Nieces Thrice Removed Thrice Removed 1 3 5 7 Thrice Removed 9 1 Instructions: For Consanguinity (relationship by blood) calculations: Place the public officer/employee for whom you need to establish relationship by consanguinity in the blank box. The labeled boxes will then list the relationships by title to the public officer/employee. Anyone in a box numbered 1, 2, or 3 is within the third degree of consanguinity. Nevada Ethics in Government Law addresses consanguinity within third degree by blood, adoption or marriage. For Affinity (relationship by marriage) calculations: Place the spouse of the public officer/employee for whom you need to establish relationship by affinity in the blank box. The labeled boxes will then list the relationships by title to the spouse and the degree of distance from the public officer/employee by affinity. A husband and wife are related in the first degree by marriage. -

Documents, Part VIII

Sec. viIi CONTENTS vIiI–1 PART VIII. GLOSSATORS: MARRIAGE CONTENTS A. GRATIAN OF BOLOGNA, CONCORDANCE OF DISCORDANT CANONS, C.27 q.2 .............VIII–2 B. PETER LOMBARD, FOUR BOOKS OF SENTENCES, 4.26–7 ...................................................VIII–12 C. DECRETALS OF ALEXANDER III (1159–1181) AND INNOCENT III (1198–1216) 1B. Veniens ... (before 1170), ItPont 3:404 .....................................................................................VIII–16 2. Sicut romana (1173 or 1174), 1 Comp. 4.4.5(7) ..........................................................................VIII–16 3. Ex litteris (1175 X 1181), X 4.16.2..............................................................................................VIII–16 4. Licet praeter solitum (1169 X 1179, probably 1176 or1177), X 4.4.3.........................................VIII–17 5. Significasti (1159 X 1181), 1 Comp. 4.4.6(8)..............................................................................VIII–18 6 . Sollicitudini (1166 X 1181), 1 Comp. 4.5.4(6) ............................................................................VIII–19 7 . Veniens ad nos (1176 X 1181), X 4.1.15 .....................................................................................VIII–19 8m. Tuas dutu (1200) .......................................................................................................................VIII–19 9 . Quod nobis (1170 or 1171), X 4.3.1 ............................................................................................VIII–19 10 . Tuae nobis -

Working Paper of Public Health Nr. 06/2014

ISSN: 2279-9761 Working paper of public health [Online] Working Paper of Public Health Nr. 06/2014 La serie di Working Paper of Public Health (WP) dell’Azienda Ospedaliera review). L’utilizzo del peer review costringerà gli autori ad adeguarsi ai di Alessandria è una serie di pubblicazioni online ed Open Access, migliori standard di qualità della loro disciplina, così come ai requisiti progressiva e multi disciplinare in Public Health (ISSN: 2279-9761). Vi specifici del WP. Con questo approccio, si sottopone il lavoro o le idee di un rientrano pertanto sia contributi di medicina ed epidemiologia, sia contributi autore allo scrutinio di uno o più esperti del medesimo settore. Ognuno di di economia sanitaria e management, etica e diritto. Rientra nella politica questi esperti fornirà una propria valutazione, includendo anche suggerimenti aziendale tutto quello che può proteggere e migliorare la salute della per l'eventuale miglioramento, all’autore, così come una raccomandazione comunità attraverso l’educazione e la promozione di stili di vita, così come esplicita al Responsabile Scientifico su cosa fare del manoscritto (i.e. la prevenzione di malattie ed infezioni, nonché il miglioramento accepted o rejected). dell’assistenza (sia medica sia infermieristica) e della cura del paziente. Si Al fine di rispettare criteri di scientificità nel lavoro proposto, la revisione sarà prefigge quindi l’obiettivo scientifico di migliorare lo stato di salute degli anonima, così come l’articolo revisionato (i.e. double blinded). individui e/o pazienti, sia attraverso la prevenzione di quanto potrebbe Diritto di critica: condizionarla sia mediante l’assistenza medica e/o infermieristica Eventuali osservazioni e suggerimenti a quanto pubblicato, dopo opportuna finalizzata al ripristino della stessa. -

THE TROLLOPE CRITICS Also by N

THE TROLLOPE CRITICS Also by N. John Hall THE NEW ZEALANDER (editor) SALMAGUNDI: BYRON, ALLEGRA, AND THE TROLLOPE FAMILY TROLLOPE AND HIS ILLUSTRATORS THE TROLLOPE CRITICS Edited by N. John Hall Selection and editorial matter © N. John Hall 1981 Softcover reprint of the hardcover 1st edition 1981 978-0-333-26298-6 All rights reserved. No part of this publication may be reproduced or transmitted, in any form or by any means, without permission First published 1981 by THE MACMILLAN PRESS LTD London and Basingstoke Companies and representatives throughout the world ISBN 978-1-349-04608-9 ISBN 978-1-349-04606-5 (eBook) DOI 10.1007/978-1-349-04606-5 Typeset in 10/12pt Press Roman by STYLESET LIMITED ·Salisbury· Wiltshire Contents Introduction vii HENRY JAMES Anthony Trollope 21 FREDERIC HARRISON Anthony Trollope 21 w. P. KER Anthony Trollope 26 MICHAEL SADLEIR The Books 34 Classification of Trollope's Fiction 42 PAUL ELMER MORE My Debt to Trollope 46 DAVID CECIL Anthony Trollope 58 CHAUNCEY BREWSTER TINKER Trollope 66 A. 0. J. COCKSHUT Human Nature 75 FRANK O'CONNOR Trollope the Realist 83 BRADFORD A. BOOTH The Chaos of Criticism 95 GERALD WARNER BRACE The World of Anthony Trollope 99 GORDON N. RAY Trollope at Full Length 110 J. HILLIS MILLER Self and Community 128 RUTH apROBERTS The Shaping Principle 138 JAMES GINDIN Trollope 152 DAVID SKILTON Trollopian Realism 160 C. P. SNOW Trollope's Art 170 JOHN HALPERIN Fiction that is True: Trollope and Politics 179 JAMES R. KINCAID Trollope's Narrator 196 JULIET McMASTER The Author in his Novel 210 Notes on the Authors 223 Selected Bibliography 226 Index 243 Introduction The criticism of Trollope's works brought together in this collection has been drawn from books and articles published since his death.