University of Cincinnati

Total Page:16

File Type:pdf, Size:1020Kb

Load more

Recommended publications

-

Nov 1973, Vector Vol. 09 No. 10

NOVEMBER 1973 “Whatapieceofworkismui!” $1.00 HEADV AT¥«EIÆ S -4, TO HAM F o r ^ 3 1 0 . 0 0 • D eparture ■ D ecem ber % ID 'S'* e s c o r t e d b y - PE:TER BESSttL ITINERARY: Depart San Francisco via United A ir Lines at 2:00PM. Arrive Los Angeles at 3:08 PM. Motor- Friday. December 7 coach transfer provided to THE BILTMORE HOTEL. Evening performance o f CA VALLERIA RUSTICANA by Mascogni and I PAGLIACCI by Leoncavallo. Depart Los Angeles by motorcoach at 11:00AM fo r Long Beach and visit to Saturday, December 8 Three hours o f leisure to browse and shop. Return to your hotel a t approximately 4.00 PM. Evening performance o f IL BARBIERE d i SEVIGLIA by Rossini. Sunday, December 9 Morning at leisure. Matinee performance o f MANON by Massenet. Evening performance o f / PURITANI by Bellini with Beverly Sills. Mondav December 10 Motorcoach transfer provided to the airport in time to depart Los Angles via United A irU n ^ Monday. December w ^an Francisco at 11:00 AM. An earlier return flight may be arranged for those who so desire. INCLUDED IN PRICE: ROUND-TRIP JET TRANSPORTATION SAN ^ R^NCISCO/LOS ANGELES/SAN F^^^^ MOTORCOACH TRANSFERS BETWEEN AIRPORT/HOTEL/AIRPORT FOR ABOVE m o t V^r c o a c h % a n s f e r s b e t w e e n h o t e l / o p e r a h o u s e / h o t e l f o r a l l PERFORMANCES. -

Aero Style Review the Outerwear Edition

AERO STYLE REVIEW THE OUTERWEAR EDITION 100 Years of Gentleman’s Clothing What the Brits Wore Aero Leather; In the Beginning The Story of The Highwayman Hard Times meant Great Jackets in USA From the Bookshelf The Label Archives ISSUE THREE A SMALL SELECTION OF AERO LABELS Page by Page: THE CONTENTS 2 100 Years of British Clothing: Saville Row to Scappa Flow No Century brought so many changes to men’s clothing as the nation went through the Class Divide, two World Wars, The General Strike, Rock’n’Roll, Psychedelia, Punk Rock and the re Birth of proper leather jackets in 1981. 6 Aero Leather Clothing: A Series of “Firsts” Classic Leather Jackets, how a small Scottish company led the revolution, bringing back lost tailoring techniques while resurrecting Horsehide as the leather of choice. 8 The Story of The Highwayman: Battersea To Greenbank Mill Perhaps the best known jacket of the last 40 years, how it went from its 1950s inception all the way to the 21st Century and back again, this time to the 1930s. 10 Hard Times but Great Jackets in USA: The Depression Years While the country suffered The Great Depression, Prohibition and The Dust Storms necessity saw the birth of some of the most outstanding jackets of the Century. 12 From the Bookcase: Essential companions for a rainy afternoon A selection of reference books recommended for collectors of vintage clothing covering Vintage Leather Jackets, The USAAF, The CC41 Scheme and Aero Leather Clothing. Cover: Luke Evans wears an Aero “Hudson”. Photo by Gavin Bond. Contents Page: Aero founder Ken Calder. -

Famous People from Czech Republic

2018 R MEMPHIS IN MAY INTERNATIONAL FESTIVAL Tennessee Academic Standards 2018 EDUCATION CURRICULUM GUIDE MEMPHIS IN MAY INTERNATIONAL FESTIVAL Celebrates the Czech Republic in 2018 Celebrating the Czech Republic is the year-long focus of the 2018 Memphis in May International Festival. The Czech Republic is the twelfth European country to be honored in the festival’s history, and its selection by Memphis in May International Festival coincides with their celebration of 100 years as an independent nation, beginning as Czechoslovakia in 1918. The Czech Republic is a nation with 10 million inhabitants, situated in the middle of Europe, with Germany, Austria, Slovakia and Poland as its neighbors. Known for its rich historical and cultural heritage, more than a thousand years of Czech history has produced over 2,000 castles, chateaux, and fortresses. The country resonates with beautiful landscapes, including a chain of mountains on the border, deep forests, refreshing lakes, as well as architectural and urban masterpieces. Its capital city of Prague is known for stunning architecture and welcoming people, and is the fifth most- visited city in Europe as a result. The late twentieth century saw the Czech Republic rise as one of the youngest and strongest members of today’s European Union and NATO. Interestingly, the Czech Republic is known for peaceful transitions; from the Velvet Revolution in which they left Communism behind in 1989, to the Velvet Divorce in which they parted ways with Slovakia in 1993. Boasting the lowest unemployment rate in the European Union, the Czech Republic’s stable economy is supported by robust exports, chiefly in the automotive and technology sectors, with close economic ties to Germany and their former countrymen in Slovakia. -

Delegates Handbook Contents

Delegates Handbook Contents Introduction 5 Czech Republic 6 - Prague 7 Daily Events and Schedule 10 Venue 13 Accreditation/ Registration 20 Facilities and Services 21 - Registration/Information Desk 21 - Catering & Coffee Breaks 21 - Business Center 21 - Additional Meeting Room 21 - Network 22 - Working Language and Interpretation 22 Accommodation 23 Transportation 24 - Airport Travel Transportation 24 - Prague Transportation 25 3 Tourism in Prague 27 Introduction - Old Town Hall with Astronomical Clock 27 - Prague Castle, St. Vitus Cathedral 28 - Charles Bridge 29 As Host Country of the XLII Antarctic Treaty - Petřín Lookout tower 30 Consultative Meeting (ATCM XLII), the Czech - Vyšehrad 30 Republic would like to give a warm welcome - Infant Jesus of Prague 31 to the Representatives of the Consultative and - Gardens and Museums 31 Non-Consultative Parties, Observers, Antarctic Treaty System bodies and Experts who participate in this Practical Information 32 meeting in Prague. - Currency, Tipping 32 This handbook contains detailed information on the - Time Zone 33 arrangements of the Meeting and useful information - Climate 33 about your stay in Prague, including the meeting - Communication and Network 34 schedule, venues and facilities, logistic services, etc. It is - Electricity 34 recommended to read the Handbook in advance to help - Health and Water Supply 35 you organize your stay. More information is available - Smoking 35 at the ATCM XLII website: www.atcm42-prague.cz. - Opening Hours of Shops 35 ATS Contacts 36 HCS Contacts 36 4 5 the European Union (EU), NATO, the OECD, the United Nations, the OSCE, and the Council of Europe. The Czech Republic boasts 12 UNESCO World Heritage Sites. -

Reason to Visit Prague

Reason to Visit Prague Largest castle complex in the world Dating back to the ninth century, Prague Castle is recognized by the Guinness Book of Records as the largest castle complex in the world, covering an impressive 70,000 square meters. The castle complex is comprised of a number of buildings, which include the gothic St. Vitus Cathedral, a number of defense towers, a few museums and churches, the presidential palace, and Golden Lane, a 16th-century street that once housed the royal goldsmiths. 1 ©2018 – 2019 TSI To admire stunning architectural masterpieces Because Prague wasn’t severely damaged during WWII, many of its most impressive historical buildings remain intact today. Thus, Prague has another major advantage going for it: while many major European capitals were rebuilt and destroyed during the 17th and 18th centuries, Prague’s buildings were left untouched. As a result, the city is a breathtaking mix of baroque, gothic and renaissance architecture, hard to find anywhere else in Europe. The Our Lady Before Týn church in Old Town Square is a magnificent example of gothic architecture, while Schwarzenberg Palace inside the Prague Castle’s grounds is a perfect example of renaissance design. Examples of cubism and neoclassicism also abound, with touches of Art Nouveau in places, such as the Municipal House. 2 ©2018 – 2019 TSI To see where Franz Kafka grew up Franz Kafka was born and grew up on the streets of Prague, not far from Old Town Square. Born into a Jewish family who spoke German (the language in which Kafka wrote all his books), Kafka was a lawyer who worked at an insurance company even though all he wanted to really do was write. -

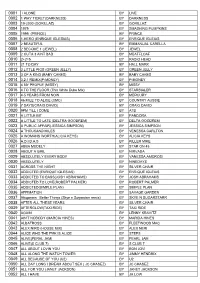

DJ Playlist.Djp

0001 I ALONE BY LIVE 0002 1 WAY TICKET(DARKNESS) BY DARKNESS 0003 19-2000 (GORILLAZ) BY GORILLAZ 0004 1979 BY SMASHING PUMPKINS 0005 1999 (PRINCE) BY PRINCE 0006 1-HERO (ENRIQUE IGLESIAS) BY ENRIQUE IGLEIAS 0007 2 BEAUTIFUL BY EMMANUAL CARELLA 0008 2 BECOME 1 (JEWEL) BY JEWEL 0009 2 OUTA 3 AINT BAD BY MEATFLOAF 0010 2+2=5 BY RADIO HEAD 0011 21 TO DAY BY HALL MARK 0012 3 LITTLE PIGS (GREEN JELLY) BY GREEN JELLY 0013 3 OF A KIND (BABY CAKES) BY BABY CAKES 0014 3,2,1 REMIX(P-MONEY) BY P-MONEY 0015 4 MY PEOPLE (MISSY) BY MISSY 0016 4 TO THE FLOOR (Thin White Duke Mix) BY STARSIALER 0017 4-5 YEARS FROM NOW BY MERCURY 0018 46 MILE TO ALICE (CMC) BY COUNTRY AUSSIE 0019 7 DAYS(CRAIG DAVID) BY CRAIG DAVID 0020 9PM TILL I COME BY ATB 0021 A LITTLE BIT BY PANDORA 0022 A LITTLE TO LATE (DELTRA GOODREM) BY DELTA GOODREM 0023 A PUBLIC AFFAIR(JESSICA SIMPSON) BY JESSICA SIMPSON 0024 A THOUSAND MILES BY VENESSA CARLTON 0025 A WOMANS WORTH(ALICIA KEYS) BY ALICIA KEYS 0026 A.D.I.D.A.S BY KILLER MIKE 0027 ABBA MEDELY BY STAR ON 45 0028 ABOUT A GIRL BY NIRVADA 0029 ABSOLUTELY EVERY BODY BY VANESSA AMOROSI 0030 ABSOLUTELY BY NINEDAYS 0031 ACROSS THE NIGHT BY SILVER CHAIR 0032 ADDICTED (ENRIQUE IGLESIAS) BY ENRIQUE IGLEIAS 0033 ADDICTED TO BASS(JOSH ABRAHAMS) BY JOSH ABRAHAMS 0034 ADDICTED TO LOVE(ROBERT PALMER) BY ROBERT PALMER 0035 ADDICTED(SIMPLE PLAN) BY SIMPLE PLAN 0036 AFFIMATION BY SAVAGE GARDEN 0037 Afropeans Better Things (Skye n Sugarstarr remix) BY SKYE N SUGARSTARR 0038 AFTER ALL THESE YEARS BY SILVER CHAIR 0039 AFTERGLOW(TAXI RIDE) BY TAXI RIDE -

Acting Hysteria: an Analysis of the Actress and Her Part

City University of New York (CUNY) CUNY Academic Works Dissertations, Theses, and Capstone Projects CUNY Graduate Center 1992 Acting Hysteria: An Analysis of the Actress and Her Part Lydia Stryk The Graduate Center, City University of New York How does access to this work benefit ou?y Let us know! More information about this work at: https://academicworks.cuny.edu/gc_etds/4291 Discover additional works at: https://academicworks.cuny.edu This work is made publicly available by the City University of New York (CUNY). Contact: [email protected] INFORMATION TO USERS This manuscript has been reproduced from the microfilm master. UMI films the text directly from the original or copy submitted. Thus, some thesis and dissertation copies are in typewriter face, while others may be from any type of computer printer. The quality of this reproduction is dependent upon the quality of the copy submitted. Broken or indistinct print, colored or poor quality illustrations and photographs, print bleedthrough, substandard margins, and improper alignment can adversely affect reproduction. In the unlikely event that the author did not send UMI a complete manuscript and there are missing pages, these will be noted. Also, if unauthorized copyright material had to be removed, a note will indicate the deletion. Oversize materials (e.g., maps, drawings, charts) are reproduced by sectioning the original, beginning at the upper left-hand corner and continuing from left to right in equal sections with small overlaps. Each original is also photographed in one exposure and is included in reduced form at the back of the book. Photographs included in the original manuscript have been reproduced xerographically in this copy. -

Song & Music in the Movement

Transcript: Song & Music in the Movement A Conversation with Candie Carawan, Charles Cobb, Bettie Mae Fikes, Worth Long, Charles Neblett, and Hollis Watkins, September 19 – 20, 2017. Tuesday, September 19, 2017 Song_2017.09.19_01TASCAM Charlie Cobb: [00:41] So the recorders are on and the levels are okay. Okay. This is a fairly simple process here and informal. What I want to get, as you all know, is conversation about music and the Movement. And what I'm going to do—I'm not giving elaborate introductions. I'm going to go around the table and name who's here for the record, for the recorded record. Beyond that, I will depend on each one of you in your first, in this first round of comments to introduce yourselves however you wish. To the extent that I feel it necessary, I will prod you if I feel you've left something out that I think is important, which is one of the prerogatives of the moderator. [Laughs] Other than that, it's pretty loose going around the table—and this will be the order in which we'll also speak—Chuck Neblett, Hollis Watkins, Worth Long, Candie Carawan, Bettie Mae Fikes. I could say things like, from Carbondale, Illinois and Mississippi and Worth Long: Atlanta. Cobb: Durham, North Carolina. Tennessee and Alabama, I'm not gonna do all of that. You all can give whatever geographical description of yourself within the context of discussing the music. What I do want in this first round is, since all of you are important voices in terms of music and culture in the Movement—to talk about how you made your way to the Freedom Singers and freedom singing. -

Compositions-By-Frank-Zappa.Pdf

Compositions by Frank Zappa Heikki Poroila Honkakirja 2017 Publisher Honkakirja, Helsinki 2017 Layout Heikki Poroila Front cover painting © Eevariitta Poroila 2017 Other original drawings © Marko Nakari 2017 Text © Heikki Poroila 2017 Version number 1.0 (October 28, 2017) Non-commercial use, copying and linking of this publication for free is fine, if the author and source are mentioned. I do not own the facts, I just made the studying and organizing. Thanks to all the other Zappa enthusiasts around the globe, especially ROMÁN GARCÍA ALBERTOS and his Information Is Not Knowledge at globalia.net/donlope/fz Corrections are warmly welcomed ([email protected]). The Finnish Library Foundation has kindly supported economically the compiling of this free version. 01.4 Poroila, Heikki Compositions by Frank Zappa / Heikki Poroila ; Front cover painting Eevariitta Poroila ; Other original drawings Marko Nakari. – Helsinki : Honkakirja, 2017. – 315 p. : ill. – ISBN 978-952-68711-2-7 (PDF) ISBN 978-952-68711-2-7 Compositions by Frank Zappa 2 To Olli Virtaperko the best living interpreter of Frank Zappa’s music Compositions by Frank Zappa 3 contents Arf! Arf! Arf! 5 Frank Zappa and a composer’s work catalog 7 Instructions 13 Printed sources 14 Used audiovisual publications 17 Zappa’s manuscripts and music publishing companies 21 Fonts 23 Dates and places 23 Compositions by Frank Zappa A 25 B 37 C 54 D 68 E 83 F 89 G 100 H 107 I 116 J 129 K 134 L 137 M 151 N 167 O 174 P 182 Q 196 R 197 S 207 T 229 U 246 V 250 W 254 X 270 Y 270 Z 275 1-600 278 Covers & other involvements 282 No index! 313 One night at Alte Oper 314 Compositions by Frank Zappa 4 Arf! Arf! Arf! You are reading an enhanced (corrected, enlarged and more detailed) PDF edition in English of my printed book Frank Zappan sävellykset (Suomen musiikkikirjastoyhdistys 2015, in Finnish). -

Idioms-And-Expressions.Pdf

Idioms and Expressions by David Holmes A method for learning and remembering idioms and expressions I wrote this model as a teaching device during the time I was working in Bangkok, Thai- land, as a legal editor and language consultant, with one of the Big Four Legal and Tax companies, KPMG (during my afternoon job) after teaching at the university. When I had no legal documents to edit and no individual advising to do (which was quite frequently) I would sit at my desk, (like some old character out of a Charles Dickens’ novel) and prepare language materials to be used for helping professionals who had learned English as a second language—for even up to fifteen years in school—but who were still unable to follow a movie in English, understand the World News on TV, or converse in a colloquial style, because they’d never had a chance to hear and learn com- mon, everyday expressions such as, “It’s a done deal!” or “Drop whatever you’re doing.” Because misunderstandings of such idioms and expressions frequently caused miscom- munication between our management teams and foreign clients, I was asked to try to as- sist. I am happy to be able to share the materials that follow, such as they are, in the hope that they may be of some use and benefit to others. The simple teaching device I used was three-fold: 1. Make a note of an idiom/expression 2. Define and explain it in understandable words (including synonyms.) 3. Give at least three sample sentences to illustrate how the expression is used in context. -

NOTICE: the Copyright Law of the United States (Title 17, United States Code) Governs the Making of Reproductions of Copyrighted Material

NOTICE: The copyright law of the United States (Title 17, United States Code) governs the making of reproductions of copyrighted material. One specified condition is that the reproduction is not to be "used for any purpose other than private study, scholarship, or research." If a user makes a request for, or later uses a reproduction for purposes in excess of "fair use," that user may be liable for copyright infringement. RESTRICTIONS: This student work may be read, quoted from, cited, for purposes of research. It may not be published in full except by permission of the author. Jacklight: Stories Table of Contents Jacklight ...................................................................................................................................... 3 The Bacchanal........................................................................................................................... 20 Wothan the Wanderer................................................................................................................ 32 Trickster Shop ........................................................................................................................... 47 Party Games .............................................................................................................................. 57 Coyote Story ............................................................................................................................. 88 2 Jacklight At thirteen, Mary discovered her first rune in a raven’s half-decayed remains. -

The Big List (My Friends Are Gonna Be) Strangers Merle Haggard 1948 Barry P

THE BIG LIST (MY FRIENDS ARE GONNA BE) STRANGERS MERLE HAGGARD 1948 BARRY P. FOLEY A LIFE THAT'S GOOD LENNIE & MAGGIE A PLACE TO FALL APART MERLE HAGGARD ABILENE GEORGE HAMILITON IV ABOVE AND BEYOND WYNN STEWART-RODNEY CROWELL ACT NATURALLY BUCK OWENS-THE BEATLES ADALIDA GEORGE STRAIT AGAINST THE WIND BOB SEGER-HIGHWAYMAN AIN’T NO GOD IN MEXICO WAYLON JENNINGS AIN'T LIVING LONG LIKE THIS WAYLON JENNINGS AIN'T NO SUNSHINE BILL WITHERS AIRPORT LOVE STORY BARRY P. FOLEY ALL ALONG THE WATCHTOWER BOB DYLAN-JIMI HENDRIX ALL I HAVE TO DO IS DREAM EVERLY BROTHERS ALL I HAVE TO OFFER IS ME CHARLIE PRIDE ALL MY EX'S LIVE IN TEXAS GEORGE STRAIT ALL MY LOVING THE BEATLES ALL OF ME WILLIE NELSON ALL SHOOK UP ELVIS PRESLEY ALL THE GOLD IN CALIFORNIA GATLIN BROTHERS ALL YOU DO IS BRING ME DOWN THE MAVERICKS ALMOST PERSUADED DAVID HOUSTON ALWAYS LATE LEFTY FRIZZELL-DWIGHT YOAKAM ALWAYS ON MY MIND ELVIS PRESLEY-WILLIE NELSON ALWAYS WANTING YOU MERLE HAGGARD AMANDA DON WILLIAMS-WAYLON JENNINGS AMARILLO BY MORNING TERRY STAFFORD-GEORGE STRAIT AMAZING GRACE TRADITIONAL AMERICAN PIE DON McLEAN AMERICAN TRILOGY MICKEY NEWBERRY-ELVIS PRESLEY AMIE PURE PRAIRIE LEAGUE ANGEL FLYING TOO CLOSE WILLIE NELSON ANGEL OF LYON TOM RUSSELL-STEVE YOUNG ANGEL OF MONTGOMERY JOHN PRINE-BONNIE RAITT-DAVE MATTHEWS ANGELS LIKE YOU DAN MCCOY ANNIE'S SONG JOHN DENVER ANOTHER SATURDAY NIGHT SAM COOKE-JIMMY BUFFET-CAT STEVENS ARE GOOD TIMES REALLY OVER MERLE HAGGARD ARE YOU SURE HANK DONE IT WAYLON JENNINGS AUSTIN BLAKE SHELTON BABY PLEASE DON'T GO MUDDY WATERS-BIG JOE WILLIAMS BABY PUT ME ON THE WAGON BARRY P.