Copyrighted Material

Total Page:16

File Type:pdf, Size:1020Kb

Load more

Recommended publications

-

AM One-Sheet W Logo Revised121913

One of the most durable and worthwhile jewels in public television’s crown. TV Worth Watching American Masters , THIRTEEN’s award-winning biography series, celebrates our arts and culture. Created and launched in 1986 by Susan Lacy, the series set the standard for documentary film profiles, accruing widespread critical acclaim. Awards include 67 Emmy nominations and 26 awards — nine for Outstanding Non-Fiction Series since 1999 and five for Outstanding Non-Fiction Special — 12 Peabody Awards; three Grammys; an Oscar; two Producers Guild Awards for Outstanding Producer of Non-Fiction Television; and the 2012 IDA Award for Best Continuing Series. American Masters enjoys recognition from film events across the country and international festivals from London to Berlin and Toronto to Melbourne. Other honors include The Christopher Awards and the Chicago International Television Awards as Outstanding Documentary Series, and the Banff Grand Prize and the Television Critics Association Award for Outstanding Movies. When it comes to biography, no one’s doing it better than American Masters. Wall Street Journal American Masters has produced an exceptional library, bringing unique originality and perspective to exploring the lives and illuminating the creative journeys of our most enduring writers, musicians, visual and performing artists, dramatists, filmmakers and those who have left an indelible impression on our cultural landscape. Balancing a broad and diverse cast of characters and artistic approaches, while preserving historical authenticity and intellectual integrity, these portraits reveal the style and substance of each subject. The series enters its 28 th season on PBS in 2014 beginning with Salinger — premiering January 21 on PBS (check local listings) — the series’ 200 th episode. -

Executive Order 13978 of January 18, 2021

6809 Federal Register Presidential Documents Vol. 86, No. 13 Friday, January 22, 2021 Title 3— Executive Order 13978 of January 18, 2021 The President Building the National Garden of American Heroes By the authority vested in me as President by the Constitution and the laws of the United States of America, it is hereby ordered as follows: Section 1. Background. In Executive Order 13934 of July 3, 2020 (Building and Rebuilding Monuments to American Heroes), I made it the policy of the United States to establish a statuary park named the National Garden of American Heroes (National Garden). To begin the process of building this new monument to our country’s greatness, I established the Interagency Task Force for Building and Rebuilding Monuments to American Heroes (Task Force) and directed its members to plan for construction of the National Garden. The Task Force has advised me it has completed the first phase of its work and is prepared to move forward. This order revises Executive Order 13934 and provides additional direction for the Task Force. Sec. 2. Purpose. The chronicles of our history show that America is a land of heroes. As I announced during my address at Mount Rushmore, the gates of a beautiful new garden will soon open to the public where the legends of America’s past will be remembered. The National Garden will be built to reflect the awesome splendor of our country’s timeless exceptionalism. It will be a place where citizens, young and old, can renew their vision of greatness and take up the challenge that I gave every American in my first address to Congress, to ‘‘[b]elieve in yourselves, believe in your future, and believe, once more, in America.’’ Across this Nation, belief in the greatness and goodness of America has come under attack in recent months and years by a dangerous anti-American extremism that seeks to dismantle our country’s history, institutions, and very identity. -

The Schlesinger Library Now in Another Portrait Within the Library

The Schlesinger A FITTING HOME FOR FFL’S RECORD OF ADVOCACY Library ON BEHALF OF WOMEN AND CHILDREN by Jane M. Rohan to documenting the lives and historical with the founding of Mother’s Day with endeavors of women, the library is her “Mother’s Day Proclamation.” Wreturned to Boston in spring $&'$( 2010 to address students at several area )*))+-!// The library has two highly distinguished 34)* )<[ members paid a special visit to the Arthur "////3)$) #)[ and Elizabeth Schlesinger Library on audiovisual material (roughly 90,000). centuries of global cuisine and includes the History of Women in America. The #4# !///4)) Schlesinger Library, which is part of the \#N: = Radcliffe Institute for Advanced Study R4N$ Elizabeth David, and Julia Child. When at Harvard University, is located on the rich collection of artifacts housed at > former campus of Radcliffe College in the Schlesinger, and a portrait of the ?@#&[ Cambridge, Massachusetts. This newly aviation pioneer who disappeared while March 2009, they were able to view its \$[$# beloved donation from Julia Child, which the world’s largest and most prestigious the library. includes one of her copper pots, her archive of women’s history. #4$)< Julia Ward Howe, a prominent American Schlesinger Library was an important !"#$ abolitionist and social activist, is featured resource for Nora Ephron’s recent donation, the Schlesinger Library now in another portrait within the library. The ))[Julie and Julia. includes the correspondence of many poet most famous for writing “The Battle [## Hymn of the Republic” later became a The second special collection, the activists, and missionaries. Dedicated )[<$ archives of Radcliffe College, documents ® THE AMERICAN FEMINIST 13 powerful story of strong women and their efforts.” Z:)[/-//=:$ @\)R >K me on a tour of the Schlesinger. -

Page 1 16 COCO CHANEL August 19, 1883–January 10, 1971

COCO CHANEL August 19, 1883–January 10, 1971 Designed costumes for Jean Cocteau’s Lived with ETIENNE Balsan in Her life story was the basis for the ANTIGONE, Orpheus & Oedipus Deauville, France Broadway MUSICAL Coco (1969) Rex Made a FASHION comeback in 1954 Raised in an ORPHANAGE ARTHUR Capel helped finance her GABRIELLE Bonheur Chanel Closed her business at the first shop (full name) OUTBREAK of World War II Ernest BEAUX helped her create her Romantically involved with Hans Launched “Chanel No. 5” PERFUME perfume GÜNTHER von Dincklage, a in 1920s Opened additional stores in Deauville German officer Pablo PICASSO (friend) & BIARRITZ, France First designer to use JERSEY for Had a decades long ROMANCE with The “little BLACK dress” women’s clothing the Duke of Westminster Had a brief CAREER as a singer Introduced costume JEWELRY to high Designed costumes for Ballets RUSSES Revolutionized women’s CLOTHING fashion Born in SAUMUR, France Jean COCTEAU (friend) Her clothing borrowed elements from Worked as a SHOPGIRL First major fashion DESIGNER to MENSWEAR Introduced the Chanel SUIT (1925) introduce a perfume Opened a MILLINERY shop in Paris Created clothes for Gloria Swanson in Greta Garbo & Marlene DIETRICH (1910) the film TONIGHT or Never were clients E S I Z E C D L C E I K F Y A Z L M N A T R O G W Y A A R R T T L R Y I I A A G R E S E T K O E E G R N E U J L R H N H S E N P I A A N N C E B I I U R U O I H R T E Y N W T O L R B H I P G H B N W S E U N L C S I R T E H W A Q S J O D I L E O A R A N T I G O N E Z M O H C I R T E I D U R S -

Women of Power 3-5

Women of Power Author: National Constitution Center staff About this Lesson This lesson, which includes a pre-lesson and post-lesson, is intended to be used in conjunction with the National Constitution Center’s Women of Power program. Together, they provide students with an overview of the contributions made by powerful women throughout United States history. In this lesson, students begin by testing their knowledge of how famous men and women have impacted the country’s cultural, social, political and economic development since the colonial period. After the NCC program, students learn about the mission of the National Women’s Hall of Fame, located in Seneca Falls, NY. They research different members of the Hall and conclude the lesson by participating in a Hall of Famer Hobnob. Designed for students in grade 3-5, this lesson takes approximately three to four class periods from beginning to end. Women of Power National Constitution Center Classroom Ready Resource Background Grade(s) Level Throughout United States history, women have made 3-5 significant contributions to the country’s cultural, social, political and economic development. From the colonial Classroom Time period to 2010, from Dolley Madison to Hillary Rodham One 45-minute class Clinton, women have influenced everything from period (pre-lesson) legislation to the arts. Two or three 45-minute The purpose of the National Constitution Center’s Women periods (post-lesson) of Power program, and of this accompanying lesson, is to Handouts offer students an opportunity to learn more about how women have shaped the U.S. throughout history. Even Who Am I? Part One though women did not get the right to vote until the student worksheet Nineteenth Amendment was ratified in 1920, their actions have affected life in the U.S. -

2006 Ralph Lowell Award—Call for Nominations

2016 Ralph Lowell Award—Call for Nominations The Corporation for Public Broadcasting (CPB) recognizes outstanding contributions to public television by presenting the Ralph Lowell medal, public television’s most prestigious award. CPB invites you to nominate individuals for the 2016 Ralph Lowell Award. The Ralph Lowell Award is named after the Boston philanthropist, banker and pioneer public broadcaster and was created by the Lowell family in 1970 to commemorate Lowell’s 80th birthday. Presented by CPB on behalf of the Lowell family, the Ralph Lowell Award honors an individual who has made an outstanding contribution to public television. NOMINATION PROCESS: Anyone inside or outside public television may submit nominations. No forms are required to nominate an individual for the Lowell Award. Please provide a letter of nomination, with specific references to the nominee’s achievements in or contributions to public television, and include a biographical sketch of the nominee. Nominations may be sent electronically to [email protected] and must be received by 5 pm EDT on April 25, 2016. SELECTION PROCESS: CPB will convene a selection committee comprising a member of the CPB Board of Directors and at least two public television system representatives. The selection committee will use the following criteria in making its decision: The medal is given to an individual for outstanding achievements in or contributions to public television. Contributions or achievements may have occurred over many years or during a short period. Contributions or achievements may include any facet of public television, including leadership, production, innovation, education or professional development. The nominee need not be a professional in public television but should be active in fostering the medium. -

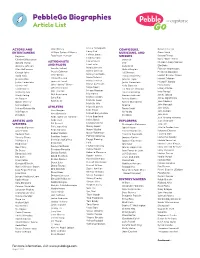

Pebblego Biographies Article List

PebbleGo Biographies Article List Kristie Yamaguchi ACTORS AND Walt Disney COMPOSERS, Delores Huerta Larry Bird ENTERTAINERS William Carlos Williams MUSICIANS, AND Diane Nash LeBron James Beyoncé Zora Neale Hurston SINGERS Donald Trump Lindsey Vonn Chadwick Boseman Beyoncé Doris “Dorie” Miller Lionel Messi Donald Trump ASTRONAUTS BTS Elizabeth Cady Stanton Lisa Leslie Dwayne Johnson AND PILOTS Celia Cruz Ella Baker Magic Johnson Ellen DeGeneres Amelia Earhart Duke Ellington Florence Nightingale Mamie Johnson George Takei Bessie Coleman Ed Sheeran Frederick Douglass Manny Machado Hoda Kotb Ellen Ochoa Francis Scott Key Harriet Beecher Stowe Maria Tallchief Jessica Alba Ellison Onizuka Jennifer Lopez Harriet Tubman Mario Lemieux Justin Timberlake James A. Lovell Justin Timberlake Hector P. Garcia Mary Lou Retton Kristen Bell John “Danny” Olivas Kelly Clarkson Helen Keller Maya Moore Lynda Carter John Herrington Lin-Manuel Miranda Hillary Clinton Megan Rapinoe Michael J. Fox Mae Jemison Louis Armstrong Irma Rangel Mia Hamm Mindy Kaling Neil Armstrong Marian Anderson James Jabara Michael Jordan Mr. Rogers Sally Ride Selena Gomez James Oglethorpe Michelle Kwan Oprah Winfrey Scott Kelly Selena Quintanilla Jane Addams Michelle Wie Selena Gomez Shakira John Hancock Miguel Cabrera Selena Quintanilla ATHLETES Taylor Swift John Lewis Alex Morgan Mike Trout Will Rogers Yo-Yo Ma John McCain Alex Ovechkin Mikhail Baryshnikov Zendaya Zendaya John Muir Babe Didrikson Zaharias Misty Copeland Jose Antonio Navarro ARTISTS AND Babe Ruth Mo’ne Davis EXPLORERS Juan de Onate Muhammad Ali WRITERS Bill Russell Christopher Columbus Julia Hill Nancy Lopez Amanda Gorman Billie Jean King Daniel Boone Juliette Gordon Low Naomi Osaka Anne Frank Brian Boitano Ernest Shackleton Kalpana Chawla Oscar Robertson Barbara Park Bubba Wallace Franciso Coronado Lucretia Mott Patrick Mahomes Beverly Cleary Candace Parker Jacques Cartier Mahatma Gandhi Peggy Fleming Bill Martin Jr. -

Cook, Frances D

The Association for Diplomatic Studies and Training Foreign Affairs Oral History Project Women Ambassadors Series AMBASSADOR FRANCES COOK Interviewed by: Ann Miller Morin Initial interview date: December 9, 1986 Copyright 2 2 ADST TABLE OF CONTENTS Bac ground Early Years in West Virginia and Florida Very Early Interest in the Foreign Service High School Interest in Politics Mary Washington College of (niversity of Virginia )unior Year Abroad * Aix en Provence Summer )ob in Washington Foreign Service Written and Oral Entrance Exam Vietnam Opposition Within Beginning Class Paris ,(SIS- Staff Assistant to Ambassador Shriver.s Wife Close to /ennedy Family Press Officer at Vietnam Peace Tal s (S 0epresentative at North Vietnamese Press Conference POW2MIA Officer on Peace Tal Delegation Sydney ,(SIS- Cultural Affairs Officer Political 0eporter Contacts 3ith Aborigines Opposition to Proposed Transfer From (SIS to State Da ar ,(SIS- (niversity 4ecturer in American History Private English Tutor to President Senghor Travels in Africa 4iving Arrangements 4ifelong 4ove of Africa 4oneliness of 4iving Abroad for Women Washington (SIS Personnel Officer for Africa Year at Harvard Transfer to Department of State Director of Public Affairs in Bureau of African Affairs Mohammed Ali.s Visit to Africa Travels in Africa 3ith Andre3 Young Andre3 Young in Texas Burundi * Ambassador Surprise Notification Confirmation Hearings S3earing2in 0eception Consultations in 4ondon and Paris Principal Mission Burundi * Country Operation European Opposition to American Activities -

Program Listings” (USPS James W

WXXI-TV/HD | WORLD | CREATE | AM1370 | CLASSICAL 91.5 | WRUR 88.5 | THE LITTLE PROGRAMPUBLIC TELEVISION & PUBLIC RADIO FOR ROCHESTER LISTINGSSEPTEMBER 2016 Julia Child’s SEE WXXI’S SPECIAL 50TH ANNIVERSARY THE FRENCH CHEF INSERT INSIDE! CHOCOLATE MOUSSE AND CARAMEL CUSTARD TUESDAY, SEPTEMBER 6 AT 8PM ON WXXI-TV As WXXI looks back on 50 years, we invite you to step back in time and relive the magic of The French Chef: Chocolate Mousse and Caramel Custard, the first program that aired on Channel 21on September 6, 1966. Join Julia Child on WXXI’s anniversary date as she cooks her famous Chocolate Mousse and we look back to pay tribute to the woman who was the first to host a national television cooking series – a program genre now a mainstay for TV viewers everywhere. Grab your mixing bowls and aprons, because it’s time to get to the kitchen! CLASSICAL 91.5 LIVE REMOTE FROM THE CLOTHESLINE ARTS FESTIVAL SATURDAY, SEPTEMBER 10, 1-3PM DETAILS INSIDE >> DANIELLE PONDER AND THE TOMORROW PEOPLE THE LITTLE THEATRE, FRIDAY, SEPTEMBER 9 AT 8PM DETAILS INSIDE >> OVER THE DECADES As we celebrate our 50th anniversary, we thought we’d share some program guide covers designed over the years. EXECUTIVE STAFF DEAR FRIENDS, SEPTEMBER 2016 No rm Silverstein, President On September 6, WXXI begins celebrating its VOLUME 7, ISSUE 9 Susan Rogers, Executive Vice President and General Manager 50th anniversary. When I think about the men and WXXI is a public non-commercial Je anne E. Fisher, Vice President, Radio women who had the foresight and the courage broadcasting station owned and operated by WXXI Public Kent Hatfield, Vice President, Technology and Operations to fight the battles to bring public television to Broadcasting Council, a not-for- El issa Orlando, Senior Vice President of TV and News the Greater Rochester area, I think about their profit corporation chartered by passion, commitment and vision. -

Demonstrating Feminist Metic Intelligence Through the Embodied Rhetorical Practices of Julia Child

University of Rhode Island DigitalCommons@URI Open Access Dissertations 2018 Demonstrating Feminist Metic Intelligence Through the Embodied Rhetorical Practices of Julia Child Lindy E. Briggette University of Rhode Island, [email protected] Follow this and additional works at: https://digitalcommons.uri.edu/oa_diss Recommended Citation Briggette, Lindy E., "Demonstrating Feminist Metic Intelligence Through the Embodied Rhetorical Practices of Julia Child" (2018). Open Access Dissertations. Paper 730. https://digitalcommons.uri.edu/oa_diss/730 This Dissertation is brought to you for free and open access by DigitalCommons@URI. It has been accepted for inclusion in Open Access Dissertations by an authorized administrator of DigitalCommons@URI. For more information, please contact [email protected]. DEMONSTRATING FEMINIST METIC INTELLIGENCE THROUGH THE EMBODIED RHETORICAL PRACTICES OF JULIA CHILD BY LINDY E. BRIGGETTE A DISSERTATION SUBMITTED IN PARTIAL FULFILLMENT OF THE REQUIREMENTS FOR THE DEGREE OF DOCTOR OF PHILOSOPHY IN ENGLISH UNIVERSITY OF RHODE ISLAND 2018 DOCTOR OF PHILOSOPHY DISSERTATION OF LINDY E. BRIGGETTE APPROVED: Dissertation Committee: Major Professor Nedra Reynolds Stephanie West-Puckett Leslie Kealhofer-Kemp Nassar H. Zawia, DEAN OF THE GRADUATE SCHOOL UNIVERSITY OF RHODE ISLAND 2018 ABSTRACT The concept of metis reinserts the body and its intelligences into the ways in which rhetoric is understood, harnessed, and performed. Originating from the wisdom of Greek goddess Metis, the concept of metis is commonly understood as cunning intelligence that is deployed in order to escape an adversary, trick an opponent, or dupe its victim. When metic intelligence is read through the helping acts of Metis and her daughter, goddess Athena, however, an expanded version of its ways of operating begins to emerge. -

Women Subjects on U.S. Postage Stamps

Women Subjects on United States Postage Stamps Queen Isabella of Spain appeared on seven stamps in the Columbian Exposition issue of 1893 — the first commemorative U.S. postage stamps. The first U.S. postage stamp to honor an American woman was the eight-cent Martha Washington stamp of 1902. The many stamps issued in honor of women since then are listed below. Martha Washington was the first American woman honored on a U.S. postage stamp. Subject Denomination Date Issued Columbian Exposition: Columbus Soliciting Aid from Queen Isabella 5¢ January 1893 Columbus Restored to Favor 8¢ January 1893 Columbus Presenting Natives 10¢ January 1893 Columbus Announcing His Discovery 15¢ January 1893 Queen Isabella Pledging Her Jewels $1 January 1893 Columbus Describing His Third Voyage $3 January 1893 Queen Isabella and Columbus $4 January 1893 Martha Washington 8¢ December 1902 Pocahontas 5¢ April 26, 1907 Martha Washington 4¢ January 15, 1923 “The Greatest Mother” 2¢ May 21, 1931 Mothers of America: Portrait of his Mother, by 3¢ May 2, 1934 James A. McNeil Whistler Susan B. Anthony 3¢ August 26, 1936 Virginia Dare 5¢ August 18, 1937 Martha Washington 1½¢ May 5, 1938 Louisa May Alcott 5¢ February 5, 1940 Frances E. Willard 5¢ March 28, 1940 Jane Addams 10¢ April 26, 1940 Progress of Women 3¢ July 19, 1948 Clara Barton 3¢ September 7, 1948 Gold Star Mothers 3¢ September 21, 1948 Juliette Gordon Low 3¢ October 29, 1948 Moina Michael 3¢ November 9, 1948 Betsy Ross 3¢ January 2, 1952 Service Women 3¢ September 11, 1952 Susan B. Anthony 50¢ August 25, -

Knife Skills

KNIFE SKILLS An Oscar®–Nominated Short Subject Documentary (40 Minutes) from Academy Award®–Winning Director Thomas Lennon (The Blood of Yingzhou District) Knife Skills follows the launch of an haute cuisine restaurant in Cleveland, staffed by men and women recently released from prison. It is a film about re-entry, second chances, and the healing power of fine food. Over 650,000 people are released from prison every year. Trailer for Knife Skills https://vimeo.com/227171872 Darwin Hailey, trainee at Edwins. After graduating from Edwins, Darwin rose to become sous chef at the restaurant. Photo Credit: Lara Talevski Marley Kichinka, trainee, previously struggled with heroin addiction; at Edwins she discovered a passion for restaurant work. 1 Synopsis What does it take to build a world-class French restaurant? What if the staff is almost entirely men and women just out of prison? What if most have never cooked or served before, and have barely two months to learn their trade? Knife Skills follows the hectic launch of Edwins restaurant in Cleveland, Ohio. In this improbable setting, with its mouthwatering dishes and its arcane French vocabulary, we discover the challenges of men and women finding their way after their release. We come to know three trainees intimately, as well as the restaurant’s founder, who is also dogged by his past. They all have something to prove, and all struggle to launch new lives — an endeavor as pressured and perilous as the ambitious restaurant launch of which they are a part. Brandon Chrostowski, founder of Edwins, on his motorcycle outside the restaurant.