Phd Students of My Own, I Shall Endeavour �To Meet the High Standards You Have Set

Total Page:16

File Type:pdf, Size:1020Kb

Load more

Recommended publications

-

Technofeminism

- TechnoFeminism JUDY WAJCMAN polity 2 Technoscience Reconfigured Men and things exchange properties and replace one another; this is what gives technological projects their full savour. Bruno Latour, Aramis Feminist approaches of the 1990s and today adopt an opti mistic perspective on the nature of digital technologies and their implications for women. In doing so, they present an image of new technology as radically distinct from older technologies and, as such, positive for women. In looking forward to what these new technologies may make possi ble, they elaborate a new feminist 'imaginary' different from the 'material reality' of the existing technological order. In this way, in common with other proponents of the impact of information and biotechnologies, they dis tinguish new technologies from more established ones, and downplay any continuities between them. While attributing a technological determinism to the past, paradoxically such approaches infer a new form of technological determinism, albeit one that predicts a future that advantages women over men. The consequences of this are explored in subsequent chapters. We shall see that Technoscience Reconfigured 33 if the social relations of older technologies are presented in too rigid a form, then the new technologies come to be seen as too open and malleable. If the former give rise to an immobilizing pessimism, the latter obviate the need for feminist technopolitics. Recent studies of science and tech nology have transformed our understanding of the social relations of technologies, both old and new. What I suggest in this chapter is that the social shaping, or constructivist, perspective offers the possibility of a fruitful interchange with feminism that can overcome the unsatisfactory dualisms with which much feminist analysis has been plagued. -

13Th FLOOR ELEVATORS

13th FLOOR ELEVATORS With such a seminal album, it’s not surprising that the cover for The Psychedelic Sounds Of The 13th Floor Elevators (1966 : International Artists Artwork : John Cleveland) has been borrowed such a lot, often by psych upstarts (also leaning on the music) and CD compliers wanting some of the early sixties garage ambience to rub off on them. The result is a great display of primary colours. Artist : The Suicidal Flowers Title : The Psychedevilic Sounds Of The Suicidal Flowers / 1997 Album / Suicidal Flowers Artwork : Unknown Artist : Artist : Various Various Artists Artists Title : The Title : The Pseudoteutonic Psychedelic Sounds Of The Sounds Of The Prae-Kraut Sonic Cathedral Pandaemonium # / 2010 14 / 2003 Album / Sonic Album / Lost Cathedral Continence Recordings Artwork / Artwork : Jimmy Reinhard Gehlen Young - Andrea Duwa - Splash 1 COVERED! PAGE 6 1 LEONA ANDERSON ASH RA TEMPEL Leona Anderson’s 1958 long-player Music To Suffer By (Unique Records) This copy of Ash Ra Tempel’s 1973 album is a gem, though I must admit I’ve never been able to get vinyl albums Starring Rosi lovingly recreates Peter to shatter quite like that (or the Buzzcocks TV show intro). The Makers Geitner’s original (cover photo : Claus have actually copied the original image for their EP and then just Kranz). added a new label design. Artist : Magic Aum Gigi Title : Starring Keiko/ 2000? Album / Fractal Records Artwork : Peter Artist : The Geitner (Photo : Makers Magic Aum Gigi) Title : Music To Suffer By / 1995 3 track EP / Estrus Wreckers Artwork : Art Chantry Artist : Smiff-N- Artist : Pavement Wessum Title : Watery, Title : Dah Shinin’ Domestic / 1992 / 1995 EP / Matador Album / Wreck Records Records Artwork : Unknown Artwork : C.M.O.N. -

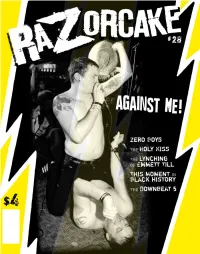

At Thirty-Three, My Anger Hasn't Subsided. It's Gotten

t thirty-three, my anger hasn’t subsided. It’s gotten And to all this, I don’t have a real answer. I don’t think I’m naïve. I deeper. It’s more like magma keeping me warm instead of lava don’t think I’m expecting too much, but it’s hard not to feel shat upon by AAshooting haphazardly all over the place. It’s managed. You see, the world-at-large every step of the way. There are a couple of things that I’ve been able to channel the balled-fist, I’m hitting-walls-and-breaking- temper my anger. First off, when we were doing our math, I got another knuckles anger into something of a long-burning fuse. Oh, I’m angry, but number: sixty-four. That’s how many folks help out Razorcake in some I’m probably one of the calmest angry people you’re likely to meet. I take way, shape, or form on a regular basis. Damn, that’s awesome. Sixty- all of my “fuck yous” and edit. I take my “you’ve got to be fucking kid- four people, without whom this zine would just be a hair-brained ding me”s and take pictures and write. I seek revenge by working my ass scheme. off. Anger, coupled with belief, is a powerful motivator. The second element is a little harder to explain. Recently, I was in an What do I have to be angry about? I don’t think it’s obvious, but we do adjacent town, South Pasadena. -

Stray Feline Adopts NW Family by BRIAN BRANDAU FEATURES EDITOR a New Tenant Recently Took up Residence in the Courtyard Village for a Few Weeks

Volume 84 - Issue 6 October 14, 2011 Stray feline adopts NW family BY BRIAN BRANDAU FEATURES EDITOR A new tenant recently took up residence in the Courtyard Village for a few weeks. An orange-white, stray cat first appeared around Northwestern’s campus about three weeks ago. Senior Krystina Bouchard and her PHOTO BY BOB LATCHAW husband, Ty, were the first Senior Isaac Hendricks wears justice clothing, clothes whose prof- students to interact with the its benefit charities. cat when it showed up at their apartment off campus. Clothes that change lives “I had just come back from BY KAMERON TOEWS grocery shopping, and there Just a few years ago, justice clothing began to appear on was this poor little kitty,” Northwestern students’ backs and feet. Bouchard said. TOMS, To Write Love On Her Arms, Clothe Your Neighbor It didn’t take long for as Yourself and Hope for Haiti clothing were spotted around Kyrstina Bouchard and her campus. Even today, these same types of clothing are still a husband to let the cat into popular choice. their apartment, but the As the trend continues to grow, more students are arrangements were not ideal questioning whether or not buying a justice organization’s for a cat to live there. Ty has PHOTO SUBMITTED clothing is a healthy way of supporting that charity. Junior allergies, and the couple Senior Natalia Mueller holds an outdoor cat that has been cared for by residents of the Courtyard Villages before finding a new home with junior Tyler McKenney’s family in Inwood. Jeremy Bork thinks purchasing justice clothing is a good way has a large dog named Dré. -

Dec. 22, 2015 Snd. Tech. Album Arch

SOUND TECHNIQUES RECORDING ARCHIVE (Albums recorded and mixed complete as well as partial mixes and overdubs where noted) Affinity-Affinity S=Trident Studio SOHO, London. (TRACKED AND MIXED: SOUND TECHNIQUES A-RANGE) R=1970 (Vertigo) E=Frank Owen, Robin Geoffrey Cable P=John Anthony SOURCE=Ken Scott, Discogs, Original Album Liner Notes Albion Country Band-Battle of The Field S=Sound Techniques Studio Chelsea, London. (TRACKED AND MIXED: SOUND TECHNIQUES A-RANGE) S=Island Studio, St. Peter’s Square, London (PARTIAL TRACKING) R=1973 (Carthage) E=John Wood P=John Wood SOURCE: Original Album liner notes/Discogs Albion Dance Band-The Prospect Before Us S=Sound Techniques Studio Chelsea, London. (PARTIALLY TRACKED. MIXED: SOUND TECHNIQUES A-RANGE) S=Olympic Studio #1 Studio, Barnes, London (PARTIAL TRACKING) R=Mar.1976 Rel. (Harvest) @ Sound Techniques, Olympic: Tracks 2,5,8,9 and 14 E= Victor Gamm !1 SOUND TECHNIQUES RECORDING ARCHIVE (Albums recorded and mixed complete as well as partial mixes and overdubs where noted) P=Ashley Hutchings and Simon Nicol SOURCE: Original Album liner notes/Discogs Alice Cooper-Muscle of Love S=Sunset Sound Recorders Hollywood, CA. Studio #2. (TRACKED: SOUND TECHNIQUES A-RANGE) S=Record Plant, NYC, A&R Studio NY (OVERDUBS AND MIX) R=1973 (Warner Bros) E=Jack Douglas P=Jack Douglas and Jack Richardson SOURCE: Original Album liner notes, Discogs Alquin-The Mountain Queen S= De Lane Lea Studio Wembley, London (TRACKED AND MIXED: SOUND TECHNIQUES A-RANGE) R= 1973 (Polydor) E= Dick Plant P= Derek Lawrence SOURCE: Original Album Liner Notes, Discogs Al Stewart-Zero She Flies S=Sound Techniques Studio Chelsea, London. -

Musician and Composer Owen Pallett on Being Thoughtful About Each Decision You Make

To help you grow your creative practice, our website is available as an email. Subscribe The Creative Independent is a vast resource of emotional and practical guidance. We publish Guides, Focuses, Tips, Interviews, and more to help you thrive as a creative person. Explore our website to find wisdom that speaks to you and your practice… September 3, 2020 - As told to Max Mertens, 2681 words. Tags: Music, Film, Inspiration, Process, Identity, Production, Multi-tasking. On being thoughtful about each decision you make Musician and composer Owen Pallett on maintaining a punk ethos in the world of chamber music, their fool-proof lyric writing method, revisiting old work, and negative inspiration. This is your first solo album in six years, but you’ve been busy in that time with different scores and arranging for other musicians. Did these projects take any creative or financial pressure off you when it came to making this record? Sometimes they do and sometimes they don’t really. Film scores are always kind of a bit of a crapshoot. If you score a film and it becomes a bit of a hit, then you do get residuals off it, so it is a good investment if you pick the right films. I notoriously have a bit of a bad nose for a good script. Back in 2008 or 2007, Gus Van Sant was asking me to possibly score Milk prior to studio involvement, and I remember reading the script and thinking it was bullshit. It won an Oscar for Best Original Screenplay, and I was like “Oh wow, I don’t really have a good nose for that kind of stuff.” Most of the production work and arrangement work that I do is a little more labor of love. -

Beats of Your Town

BEATS OF YOUR TOWN On the eve of the release of their new album ‘Ocean’s Apart’, Grant McLennan, co-leader of watershed Brisbane pop group, The Go-Betweens, takes the time to grant Robiter an interview. Matthew ‘The Rock Lobbster’ Lobb reports The Clowns Come To Town – Film School Rejections and UQ Librarians Long before Queensland art tangled at a pretty summit with pop music (the years prior to LP wonderworks such as Before Hollywood, Liberty Belle And The Black Diamond Express and 16 Lovers Lane) , one Grant McLennan had been knocked back from film and television school on account of his 16 years. Enrolment in an arts program at the University of Queensland came, therefore, as a sort of edifying compromise. Once at St. Lucia, the undergraduate - a brainy eldest child from rural Queensland - befriended a gracefully mincing eccentric named Robert Forster who played guitar and wrote his own songs. The two bonded over shared tastes in skewered pop culture and spent a lot of time at the Humanities library reading, in import copies of The Village Voice, about emerging bands like Television and Talking Heads. Go-Betweens circa '78: Librarians Beware No doubt McLennan was more OCEAN’S APART PICKED APART Grant talks Robiter through the new studious than his pal who failed both at arts and at convincing him to album form a rock group. While a disciplined McLennan passed classes with focused endeavour, Forster was crashing heavily and channelling his ‘Here Comes A City’ (the first vigour into composing songs about would-be love interests. -

Joanna Newsom Covers in the Blogosphere Shayne Pepper Northeastern Illinois University, [email protected]

Northeastern Illinois University NEIU Digital Commons Communication, Media and Theatre Faculty Communication, Media and Theatre Publications 2010 Joanna Newsom Covers in the Blogosphere Shayne Pepper Northeastern Illinois University, [email protected] Follow this and additional works at: https://neiudc.neiu.edu/cmt-pub Part of the Film and Media Studies Commons, and the Other Music Commons Recommended Citation Pepper, Shayne, "Joanna Newsom Covers in the Blogosphere" (2010). Communication, Media and Theatre Faculty Publications. 3. https://neiudc.neiu.edu/cmt-pub/3 This Book Chapter is brought to you for free and open access by the Communication, Media and Theatre at NEIU Digital Commons. It has been accepted for inclusion in Communication, Media and Theatre Faculty Publications by an authorized administrator of NEIU Digital Commons. For more information, please contact [email protected],[email protected],[email protected]. Joanna Newsom Covers in the Blogosphere Shayne Pepper “This is an old song. These are old blues. And this is not my song, but it’s mine to use.” -- “Sadie” Joanna Newsom’s 2004 album, The Milk-Eyed Mender, was released at a time when music blogs were reaching new levels of popularity within certain sections of music and online communities. During this time, songs from nearly every high profile indie rock release seemed to find their way onto music blogs (often, to the chagrin of the music industry, far before slated release dates). Newsom’s songs were no exception – she was often something of a hot topic on blogs like Stereogum, My Old Kentucky Blog, Brooklyn Vegan, Gorilla vs. -

Myspace.Com - - 43 - Male - PHILAD

MySpace.com - WWW.RECORDCASTLE.COM - 43 - Male - PHILAD... http://www.myspace.com/recordcastle Sponsored Links Gear Ink JazznBlues Tees Largest selection of jazz and blues t-shirts available. Over 100 styles www.gearink.com WWW.RECORDCASTLE.COM WWW.RECORDCASTLE.COM is in your extended "it's an abomination that we are in an network. obama nation ... ron view more paul 2012 ... balance the budget and bring back tube WWW.RECORDCASTLE.COM's Latest Blog Entry [ Subscribe to this Blog ] amps" [View All Blog Entries ] Male 43 years old PHILADELPHIA, Pennsylvania WWW.RECORDCASTLE.COM's Blurbs United States About me: I have been an avid music collector since I was a kid. I ran a store for 20 years and now trade online. Last Login: 4/24/2009 I BUY PHONOGRAPH RECORDS ( 33 lp albums / 45 rpms / 78s ), COMPACT DISCS, DVD'S, CONCERT MEMORABILIA, VINTAGE POSTERS, BEATLES ITEMS, KISS ITEMS & More Mood: electric View My: Pics | Videos | Playlists Especially seeking Private Pressings / Psychedelic / Rockabilly / Be Bop & Avant Garde Jazz / Punk / Obscure '60s Funk & Soul Records / Original Contacting WWW.RECORDCASTLE.COM concert posters 1950's & 1960's era / Original Beatles memorabilia I Offer A Professional Buying Service Of Music Items * LPs 45s 78s CDS DVDS Posters Beatles Etc.. Private Collections ** Industry Contacts ** Estates Large Collections / Warehouse finds ***** PAYMENT IN CASH ***** Over 20 Years experience buying collections MySpace URL: www.myspace.com/recordcastle I pay more for High Quality Collections In Excellent condition Let's Discuss What You May Have For Sale Call Or Email - 717 209 0797 Will Pick Up in Bucks County / Delaware County / Montgomery County / Philadelphia / South Jersey / Lancaster County / Berks County I travel the country for huge collections Print This Page - When You Are Ready To Sell Let Me Make An Offer ----------------------------------------------------------- Who I'd like to meet: WWW.RECORDCASTLE.COM's Friend Space (Top 4) WWW.RECORDCASTLE.COM has 57 friends. -

Music & Memorabilia Auction May 2019

Saturday 18th May 2019 | 10:00 Music & Memorabilia Auction May 2019 Lot 19 Description Estimate 5 x Doo Wop / RnB / Pop 7" singles. The Temptations - Someday (Goldisc £15.00 - £25.00 3001). The Righteous Brothers - Along Came Jones (Verve VK-10479). The Jesters - Please Let Me Love You (Winley 221). Wayne Cochran - The Coo (Scottie 1303). Neil Sedaka - Ring A Rockin' (Guyden 2004) Lot 93 Description Estimate 10 x 1980s LPs to include Blondie (2) Parallel Lines, Eat To The Beat. £20.00 - £40.00 Ultravox (2) Vienna, Rage In Eden (with poster). The Pretenders - 2. Men At Work - Business As Usual. Spandau Ballet (2) Journeys To Glory, True. Lot 94 Description Estimate 5 x Rock n Roll 7" singles. Eddie Cochran (2) Three Steps To Heaven £15.00 - £25.00 (London American Recordings 45-HLG 9115), Sittin' On The Balcony (Liberty F55056). Jerry Lee Lewis - Teenage Letter (Sun 384). Larry Williams - Slow Down (Speciality 626). Larry Williams - Bony Moronie (Speciality 615) Lot 95 Description Estimate 10 x 1960s Mod / Soul 7" Singles to include Simon Scott With The LeRoys, £15.00 - £25.00 Bobby Lewis, Shirley Ellis, Bern Elliot & The Fenmen, Millie, Wilson Picket, Phil Upchurch Combo, The Rondels, Roy Head, Tommy James & The Shondells, Lot 96 Description Estimate 2 x Crass LPs - Yes Sir, I Will (Crass 121984-2). Bullshit Detector (Crass £20.00 - £40.00 421984/4) Lot 97 Description Estimate 3 x Mixed Punk LPs - Culture Shock - All The Time (Bluurg fish 23). £10.00 - £20.00 Conflict - Increase The Pressure (LP Mort 6). Tom Robinson Band - Power In The Darkness, with stencil (EMI) Lot 98 Description Estimate 3 x Sub Humanz LPs - The Day The Country Died (Bluurg XLP1). -

Oslo, Norway – 31

OSLO, NORWAY – 31. MARCH - 03. APRIL 2010 MAYHEM A RETROSPECTIVE OF GIANTS A VIEW FROM BERGEN TAAKE NACHTMYSTIUM THE TRANSATLANTIC PERSPECTIVE REVELATORY, TRANSFORMATIVE MAGICK JARBOE TEN YEARS OF INFERNO – THE PEOPLE TELL THEIR STORIES OSLO SURVIVOR GUIDE – CINEMATIC INFERNO – CONFERENCE – EXPO – AND MORE WWW.ROSKILDE-FESTIVAL.DK NÅ PÅ DVD OG BLU-RAY! Photo: Andrew Parker Inferno 2010 (from left): Carolin, Jan Martin, Hilde, Anders, Runa, Torje and Melanie (not present: Lars) HAIL ALL – WELCOME TO THE INFERNO METAL FESTIVALS TEN YEAR ANNIVERSARY! n annual gathering of metal, the black and extreme, the blasphemous Aand gory – music straight from hell! Worshippers from all over the world congregate for the fest of the the black metal easter in the North. YOU are hereby summoned! ron fisted, the Inferno Fest has ruled the first decade of the new Millenn- INFERNO MAGAZINE 2010 Iium. It has been a trail of hellfire. Sagas have been written and legacies Editor: Runa Lunde Strindin carved in willing flesh with new bands and new musical territory continously Writers: Gunnar Sauermann, Jonathan Seltzer, Hilde Hammer, conquered ! Bjørnar Hagen, Trond Skog, Anders Odden, Torje Norén. Photos: Andrew Parker, Alex Sjaastad, Charlotte Christiansen, Trond Skog, ail to all the bands, the crew and the volunteers, venues and clubs! Lena Carlsen. HHail to the dedicated media, labels and managements, our partners and IMX and IMC photos: Viktor Jæger collaborators! Inferno logos and illustrations, magazine layout: Hail to the Inferno audience with their dark force and energy. Asgeir Mickelson at MultiMono (www.multimo.no) With you all onboard we set our sails for the next Inferno! Advertising: Melanie Arends and Hilde Hammer at turbine agency (www.turbine.no) Join this years fest and the forthcoming gatherings in the Distribution: turbine agency + Scream Magazine years to come. -

Kool'zine (The Go-Betweens)

Hard On For Love 38.776 caracteres alrededor de The Go- Betweens CANCIONES DE AMOR. irresponsabilidad. Todas esas cosas vienen de en - tonces; sería bonito recuperarlo, pero son otros í. Lo sé. Cuadrar al toro más lidia - tiempos…Para mi, son ideas falsas ahora. do de la música popular adolescen - Todavía creo que hay un millón de buenas razo - Ste. Conseguir que se le ericen los nes para la rebeldía…pero la gente lo esta ha - pelillos de la nuca a la puta más revisita - ciendo a partir de un esquema que existió en los da en cinco décadas de cultura musical ‘50, y la primera mitad de los ‘60. De ahí toda juvenil. Hacer CANCIONES. Punto. esa retorica y esos estúpidos sueños que la gente El Tópico entre los Tópicos, y a la vez su sigue a pesar de que están caducos desde hace propia razón de ser. treinta años…Lo veo como una trampa real, ”La fuerza que me impulsa al componer es una trampa en la que la gente joven cae, a la hacer algo totalmente inspirado y brillante, cap - que se adapta .” (RF, 2)– , y no es difícil com - turar mi vida en una canción... realmente me prender su condición de cronistas privile - gustaría escribir una canción como ‘Young Girls giados de los mil y un recorridos de la pa - Are Coming To The Canyon’ de Mamas and sión; una pasión que en un tiempo de una Papas: me gustaría escribir una realmente real - austeridad emocional espartana, obliga mente buena canción pop de tres acordes. Eso es -ineludiblemente, a cada segundo- a luchar en lo que pienso en este momento” (RF, 2).