Ancient History

Total Page:16

File Type:pdf, Size:1020Kb

Load more

Recommended publications

-

Ancient Sparta Was a Warrior Society in Ancient Greece That Reached

Ancient Sparta was a warrior society in ancient Greece that reached the height of its power after defeating rival city-state Athens in the Peloponnesian War (431-404 B.C.). Spartan culture was centered on loyalty to the state and military service. At age 7, Spartan boys entered a rigorous state-sponsored education, military training and socialization program. Known as the Agoge, the system emphasized duty, discipline and endurance. Although Spartan women were not active in the military, they were educated and enjoyed more status and freedom than other Greek women. Because Spartan men were professional soldiers, all manual labor was done by a slave class, the Helots. Despite their military prowess, the Spartans’ dominance was short-lived: In 371 B.C., they were defeated by Thebes at the Battle of Leuctra, and their empire went into a long period of decline. SPARTAN SOCIETY Sparta was an ancient Greek city-state located primarily in the present-day region of southern Greece called Laconia. The population of Sparta consisted of three main groups: the Spartans who were full citizens; the Helots, or serfs/slaves; and the Perioeci, who were neither slaves nor citizens. The Perioeci, whose name means “dwellers-around,” worked as craftsmen and traders, and built weapons for the Spartans. 3 Layers of ‘Social Stratification’ ← Top Tier: Spartan Male Warriors and Spartan Women ← Middle Tier: Non Warriors, not full citizens, considered to be outside of true Spartan society. These were artisans and merchants who made weapons and did business with the Spartans. (Perioeci) ← Helots or slaves. These were people who were conquered by the Spartans. -

Ancient History Sourcebook: 11Th Brittanica: Sparta SPARTA an Ancient City in Greece, the Capital of Laconia and the Most Powerful State of the Peloponnese

Ancient History Sourcebook: 11th Brittanica: Sparta SPARTA AN ancient city in Greece, the capital of Laconia and the most powerful state of the Peloponnese. The city lay at the northern end of the central Laconian plain, on the right bank of the river Eurotas, a little south of the point where it is joined by its largest tributary, the Oenus (mount Kelefina). The site is admirably fitted by nature to guard the only routes by which an army can penetrate Laconia from the land side, the Oenus and Eurotas valleys leading from Arcadia, its northern neighbour, and the Langada Pass over Mt Taygetus connecting Laconia and Messenia. At the same time its distance from the sea-Sparta is 27 m. from its seaport, Gythium, made it invulnerable to a maritime attack. I.-HISTORY Prehistoric Period.-Tradition relates that Sparta was founded by Lacedaemon, son of Zeus and Taygete, who called the city after the name of his wife, the daughter of Eurotas. But Amyclae and Therapne (Therapnae) seem to have been in early times of greater importance than Sparta, the former a Minyan foundation a few miles to the south of Sparta, the latter probably the Achaean capital of Laconia and the seat of Menelaus, Agamemnon's younger brother. Eighty years after the Trojan War, according to the traditional chronology, the Dorian migration took place. A band of Dorians united with a body of Aetolians to cross the Corinthian Gulf and invade the Peloponnese from the northwest. The Aetolians settled in Elis, the Dorians pushed up to the headwaters of the Alpheus, where they divided into two forces, one of which under Cresphontes invaded and later subdued Messenia, while the other, led by Aristodemus or, according to another version, by his twin sons Eurysthenes and Procles, made its way down the Eurotas were new settlements were formed and gained Sparta, which became the Dorian capital of Laconia. -

2 the Assyrian Empire, the Conquest of Israel, and the Colonization of Judah 37 I

ISRAEL AND EMPIRE ii ISRAEL AND EMPIRE A Postcolonial History of Israel and Early Judaism Leo G. Perdue and Warren Carter Edited by Coleman A. Baker LONDON • NEW DELHI • NEW YORK • SYDNEY 1 Bloomsbury T&T Clark An imprint of Bloomsbury Publishing Plc Imprint previously known as T&T Clark 50 Bedford Square 1385 Broadway London New York WC1B 3DP NY 10018 UK USA www.bloomsbury.com Bloomsbury, T&T Clark and the Diana logo are trademarks of Bloomsbury Publishing Plc First published 2015 © Leo G. Perdue, Warren Carter and Coleman A. Baker, 2015 All rights reserved. No part of this publication may be reproduced or transmitted in any form or by any means, electronic or mechanical, including photocopying, recording, or any information storage or retrieval system, without prior permission in writing from the publishers. Leo G. Perdue, Warren Carter and Coleman A. Baker have asserted their rights under the Copyright, Designs and Patents Act, 1988, to be identified as Authors of this work. No responsibility for loss caused to any individual or organization acting on or refraining from action as a result of the material in this publication can be accepted by Bloomsbury or the authors. British Library Cataloguing-in-Publication Data A catalogue record for this book is available from the British Library. ISBN: HB: 978-0-56705-409-8 PB: 978-0-56724-328-7 ePDF: 978-0-56728-051-0 Library of Congress Cataloging-in-Publication Data A catalogue record for this book is available from the British Library. Typeset by Forthcoming Publications (www.forthpub.com) 1 Contents Abbreviations vii Preface ix Introduction: Empires, Colonies, and Postcolonial Interpretation 1 I. -

The Effects of Mythos' on Plato's Educational Approach

View metadata, citation and similar papers at core.ac.uk brought to you by CORE provided by Elsevier - Publisher Connector Available online at www.sciencedirect.com Procedia - Social and Behavioral Sciences 55 ( 2012 ) 560 – 567 INTERNATIONAL CONFERENCE ON NEW HORIZONS IN EDUCATION INTE2012 The Effects of Mythos’ on Plato's Educational Approach Derya Çığır Dikyola aIstanbul University Hasan Ali Yucel Education Faculty, Department of Social Science, Istanbul, Turkey. Abstract The purpose of this study, by examining the findings related to education in Greek mythos, is to reveal Plato's contributions to the educational approach. The similarities and differences between Plato’s educational approach and the education in Mythos are emphasized in this historical - comparison based study. The effect of mythos, which in fact give ideal education of the period, with the expressions they made about Gods’ and heroes’ education, on the educational approach of Plato, known to be intensely against the mythos, is rather surprising. ©© 20122012 Published Published by byElsevier Elsevier Ltd. SelectionLtd. Selection and/or peer-reviewand/or peer-review under responsibility under responsibility of The Association of The of Association Science, of EducationScience, Educationand Technology and TechnologyOpen access under CC BY-NC-ND license. Keywords: educational approach, educational history, mythology. 1. Introduction Plato is the first thinker of philosophy as well as of education. His ideas about education still have influence on schooling. Thus; Plato is a decent starting point in the studies over the meaning and the philosophy of education. Thinkers like Aristoteles, John Locke, J. J. Rousseau, and John Dewey, who produced education theories couldn’t help challenging Plato. -

Judea/Israel Under the Greek Empires." Israel and Empire: a Postcolonial History of Israel and Early Judaism

"Judea/Israel under the Greek Empires." Israel and Empire: A Postcolonial History of Israel and Early Judaism. Perdue, Leo G., and Warren Carter.Baker, Coleman A., eds. London: Bloomsbury T&T Clark, 2015. 129–216. Bloomsbury Collections. Web. 30 Sep. 2021. <http:// dx.doi.org/10.5040/9780567669797.ch-005>. Downloaded from Bloomsbury Collections, www.bloomsburycollections.com, 30 September 2021, 15:32 UTC. Copyright © Leo G. Perdue, Warren Carter and Coleman A. Baker 2015. You may share this work for non-commercial purposes only, provided you give attribution to the copyright holder and the publisher, and provide a link to the Creative Commons licence. 5 Judea/Israel under the Greek Empires* In 33130 BCE, by military victory, the Macedonian Alexander ended the Persian Empire. He defeated the Persian king Darius at Gaugamela, advanced to a welcoming Babylon, and progressed to Persepolis where he burned Xerxes palace supposedly in retaliation for Persias invasions of Greece some 150 years previously (Diodorus 17.72.1-6). Thus one empire gave way to another by a different name. So began the Greek empires that dominated Judea/Israel for the next two hundred or so years, the focus of this chapter. Is a postcolonial discussion of these empires possible and what might it highlight? Considerable dif�culties stand in the way. One is the weight of conventional analyses and disciplinary practices which have framed the discourse with emphases on the various roles of the great men, the ruling state, military battles, and Greek settlers, and have paid relatively little regard to the dynamics of imperial power from the perspectives of native inhabitants, the impact on peasants and land, and poverty among non-elites, let alone any reciprocal impact between colonizers and colon- ized. -

Ancient History

ANCIENT HISTORY ‘The real political leadership of Sparta rested with the elders and the ephors’ (C. G. Thomas). To what extent is this an accurate description of the government of Sparta? According to both ancient and modern sources on Sparta, its’ political leadership could be perceived to be in the control of the elders, the dual kingship and the Ephors alone. However, for one to completely agree with C. G. Thomas and confirm the accuracy of his statement, the political significance of the Apella and the democratic system in ancient Sparta would have to be ignored. It is the nature of the ‘balance of power’ between these four groups, and the extent of power that is given to each, that ultimately decides the validity and truthfulness of the statement made by C.G. Thomas. One aspect of the Spartan political sphere which holds some significance is the Apella; the assembly attended by those over the age of thirty who held full citizenship. They: elected the Ephors, elders of the Gerousia and other magistrates, were responsible for passing measures put before it, such as appointments of military commanders, decisions about peace and war, resolutions for problems regarding kingship, and the emancipation of helots. However, the assembly did not debate; instead, they listened to the Kings, Ephors, and councillors. It also did not decide on the issues that would be voted on, for this was a power of the Gerousia. It would seem that however important and democratic the Apella were, they did not truly hold power. Modern historian Cartledge explains that, ‘It is hardly likely that an assembly whose members have been trained from earliest childhood to respect and unquestioningly obey their elders would easily reject a proposal of the Gerousia.’ Consequently, it would seem that the Apella is almost an unnecessary body, intended to give the feeling of order and equality amongst the Spartiates without giving any true power. -

Not All Were Created Equal

Portland State University PDXScholar Young Historians Conference 2010-2011 Past Young Historians Conference Winners May 1st, 9:00 AM - 10:00 AM Not All Were Created Equal Sarah Cox Clackamas High School Follow this and additional works at: https://pdxscholar.library.pdx.edu/younghistorians Part of the Ancient History, Greek and Roman through Late Antiquity Commons, History of Gender Commons, and the Women's History Commons Let us know how access to this document benefits ou.y Cox, Sarah, "Not All Were Created Equal" (2011). Young Historians Conference. 3. https://pdxscholar.library.pdx.edu/younghistorians/2010-2011/oralpres/3 This Event is brought to you for free and open access. It has been accepted for inclusion in Young Historians Conference by an authorized administrator of PDXScholar. Please contact us if we can make this document more accessible: [email protected]. Cox 1 Sarah Cox LPB Western Civilization: Fall Paper 9 December 2010 Not All Were Created Equal “The man’s role requires him to be outside – men who stay at home during the day are considered womanish – the woman’s requires her to work at home” (McAuslan 137). In the time-period between 700 and 300 BCE, this was often true for the women of the world, but there was one major exception: Spartan women. In most other parts of ancient Greece, women were expected to be seen and not heard. Spartan women, however, were allowed much more freedom than their contemporaries. They were allowed to own property, could live independently, and were not forced into marriage and motherhood at a young age. -

A Brief History of Classical Education

A Brief History of Classical Lesson 4: The History of Ancient Education Education Dr. Matthew Post Outline: Ancient Education and Its Questions Ancient Education is all about character formation. The question is “What sort of character?” What are the morals towards which to form students? Scholé presents another issue. Ancients had less time to devote to proper scholé. The presence of corporeal punishment was questioned by many because it seemed to treat students as slaves (coercing them to do their work through physical pain). The “intellectual life” caused controversy because it often raised questions that unsettled the normal order. (i.e. Cicero held that the ideas of the Stoics made people complacent in the face of evil and some held that Plato’s ideas inspired people to go and assassinate the ruler of their town) Roman Education Three outcomes: Philosopher, Statesman, and Soldier Discussion of Liberal Arts originates in Rome especially with Cicero (without formalization of Medieval period) Education connected to the idea of pietas (from which we get the English words “piety” and “pity”). Pietas does not mean “piety,” it means “loyalty.” o Pietas is loyalty to one’s family, people, city, and the gods. Loyalty to the gods is what the English notion of piety refers to, but pietas encompasses more. Traditional Roman education is dictated by the paterfamilias (the head of the family – a father with power over all and everything in the family). “Aeneas & Anchises” by Pierre Lepautre (a famous show of pietas) o The paterfamilias often educated the children himself. (Famously Cato the Elder educated his children.) Education in the Roman family was for both men and women though they were educated differently. -

Ancient Sparta Ancient Athens

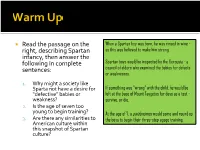

Read the passage on the When a Spartan boy was born, he was rinsed in wine - right, describing Spartan as this was believed to make him strong. infancy, then answer the following in complete Spartan boys would be inspected by the Gerousia - a sentences: council of elders who examined the babies for defects or weaknesses. 1. Why might a society like Sparta not have a desire for If something was “wrong” with the child, he would be “defective” babies or left at the base of Mount Taygetus for days as a test - weakness? survive, or die. 2. Is the age of seven too young to begin training? At the age of 7, a paidonómos would come and round up 3. Are there any similarities to the boys to begin their three-step agoge training. American culture within this snapshot of Spartan culture? Title: Comparative Study; Eastern Bloc and Worldly Civilizations Date: Know: I will be able to identify, describe, and analyze the similarities and differences of political involvement in livelihood across millennia. Relevance: Today we are learning about this because it is imperative to build knowledge in a pragmatic way – understanding that the real world and real life are connected to history is very important. Coming to this understanding is powerful! Do: I will write and discuss comparative issues between Ancient Greek city-states Do: I will write and discuss comparative issues between Medieval nations Do: I will write and discuss comparative issues between modern countries Write down the Essential Question: EQ: which child-rearing system had the greatest impact on population regulation? Warm Up Cornell Notes . -

VALOUR, DUTY, SACRIFICE: SPARTA ‘In Sparta Are to Be Found Those Who Are Most Enslaved and Those Who Are the Most Free.’

CHAPTER 2 VALOUR, DUTY, SACRIFICE: SPARTA ‘In Sparta are to be found those who are most enslaved and those who are the most free.’ CRITIAS OF ATHENS sample pages Spartan infantry in a formation called a phalanx. 38 39 CHAPTER 2 VALOUR, DUTY, SACRIFICE: SPARTA KEY POINTS KEY CONCEPTS OVERVIEW • At the end of the Dark Age, the Spartan polis emerged DEMOCRACY OLIGARCHY TYRANNY MONARCHY from the union of a few small villages in the Eurotas valley. Power vested in the hands Power vested in the hands A system under the control A system under the control • Owing to a shortage of land for its citizens, Sparta waged of all citizens of the polis of a few individuals of a non-hereditary ruler of a king war on its neighbour Messenia to expand its territory. unrestricted by any laws • The suppression of the Messenians led to a volatile slave or constitution population that threatened Sparta’s way of life, making the DEFINITION need for reform urgent. KEY EVENTS • A new constitution was put in place to ensure Sparta could protect itself from this new threat, as well as from tyranny. Citizens of the polis all A small, powerful and One individual exercises Hereditary rule passing 800 BCE • Sweeping reforms were made that transformed Sparta share equal rights in the wealthy aristocratic class complete authority over from father to son political sphere all aspects of everyday life Sparta emerges from the into a powerful military state that soon came to dominate Most citizens barred from Family dynasties claim without constraint Greek Dark Age the Peloponnese. -

One of So Very Few Herodotus Names Very Few Hellenic Women in His

2020-3890-AJHA 1 Gorgo: Sparta’s Woman of Autonomy, Authority, and Agency 2 [Hdt. 3.148–3.149, 5.42, 5.46, 5.48–5.51, 5.70, 6.65–6.67, 6.137–6.140, and Hdt. 7.238– 3 7.239] 4 5 Claims that Herodotus reveals himself as a proto-biographer, let alone as a proto- 6 feminist, are not yet widely accepted. To advance these claims, I have selected one 7 remarkable woman from one side of the Greco-Persian Wars whose activities are 8 recounted in his Histories. Critically it is to a near contemporary, Heraclitus, to 9 whom we attribute the maxim êthos anthropôi daimôn (ἦθος ἀνθρώπῳ δαίμων) — 10 character is human destiny. It is the truth of this maxim—which implies effective 11 human agency—that makes Herodotus’ creation of historical narrative even 12 possible. Herodotus is often read for his vignettes, which, without advancing the 13 narrative, color-in the character of the individuals he depicts in his Histories. No 14 matter, if these fall short of the cradle to grave accounts given by Plutarch, by hop- 15 scotching through the nine books, we can assemble a partially continuous narrative, 16 and thus through their exploits, gauge their character, permitting us to attribute both 17 credit and moral responsibility. Arguably this implied causation demonstrates that 18 Herodotus’ writings include much that amounts to proto-biography and in several 19 instances—one of which is given here—proto-feminism. 20 21 22 One of So Very Few 23 24 Herodotus names very few Hellenic women in his Histories, let alone 25 assigning many of them significant roles during the Greco-Persian Wars, but his 26 readers must readily note that in terms of political judgment he has nothing but 27 praise for one royal Spartan woman—Gorgo—who is born somewhat later than 28 Atossa of Persia but about the same time as Artemisia of Halicarnassus and is 29 therefore her contemporary 1 Women are mentioned 375 times by Herodotus 30 (Dewald 94, and 125). -

Monday 16 June 2014 – Afternoon

F Monday 16 June 2014 – Afternoon GCSE CLASSICAL CIVILISATION A353/01 Community Life in the Classical World (Foundation Tier) *1238732213* Candidates answer on the Question Paper. OCR supplied materials: Duration: 1 hour None Other materials required: None *A35301* INSTRUCTIONS TO CANDIDATES • Write your name, centre number and candidate number in the boxes above. Please write clearly and in capital letters. • Use black ink. HB pencil may be used for graphs and diagrams only. • There are two options in this paper: Option 1: Sparta, with questions starting on page 2. Option 2: Pompeii, with questions starting on page 16. • Answer questions from either Option 1 or Option 2. • Answer all questions from Section A and two questions from Section B of the option that you have studied. • Read each question carefully. Make sure you know what you have to do before starting your answer. • Write your answer to each question in the space provided. If additional space is required, you should use the lined pages at the end of this booklet. The question number(s) must be clearly shown. • Do not write in the bar codes. INFORMATION FOR CANDIDATES • The number of marks is given in brackets [ ] at the end of each question or part question. • The total number of marks for this paper is 60. • This document consists of 32 pages. Any blank pages are indicated. © OCR 2014 [A/501/5549] OCR is an exempt Charity DC (DTC 00708 10/12) 71715/3 Turn over 2 Option 1: Sparta Answer all of Section A and two questions from Section B.