A Lost Late Predynastic-Early Dynastic Royal Scene from Gharb Aswan

Total Page:16

File Type:pdf, Size:1020Kb

Load more

Recommended publications

-

An Evaluation of Two Recent Theories Concerning the Narmer Palette1

Eras Edition 8, November 2006 – http://www.arts.monash.edu.au/eras An Evaluation of Two Recent Theories Concerning the Narmer Palette1 Benjamin P. Suelzle (Monash University) Abstract: The Narmer Palette is one of the most significant and controversial of the decorated artefacts that have been recovered from the Egyptian Protodynastic period. This article evaluates the arguments of Alan R. Schulman and Jan Assmann, when these arguments dwell on the possible historicity of the palette’s decorative features. These two arguments shall be placed in a theoretical continuum. This continuum ranges from an almost total acceptance of the historical reality of the scenes depicted upon the Narmer Palette to an almost total rejection of an historical event or events that took place at the end of the Naqada IIIC1 period (3100-3000 BCE) and which could have formed the basis for the creation of the same scenes. I have adopted this methodological approach in order to establish whether the arguments of Assmann and Schulman have any theoretical similarities that can be used to locate more accurately the palette in its appropriate historical and ideological context. Five other decorated stone artefacts from the Protodynastic period will also be examined in order to provide historical comparisons between iconography from slightly earlier periods of Egyptian history and the scenes of royal violence found upon the Narmer Palette. Introduction and Methodology Artefacts of iconographical importance rarely survive intact into the present day. The Narmer Palette offers an illuminating opportunity to understand some of the ideological themes present during the political unification of Egypt at the end of the fourth millennium BCE. -

Was the Function of the Earliest Writing in Egypt Utilitarian Or Ceremonial? Does the Surviving Evidence Reflect the Reality?”

“Was the function of the earliest writing in Egypt utilitarian or ceremonial? Does the surviving evidence reflect the reality?” Article written by Marsia Sfakianou Chronology of Predynastic period, Thinite period and Old Kingdom..........................2 How writing began.........................................................................................................4 Scopes of early Egyptian writing...................................................................................6 Ceremonial or utilitarian? ..............................................................................................7 The surviving evidence of early Egyptian writing.........................................................9 Bibliography/ references..............................................................................................23 Links ............................................................................................................................23 Album of web illustrations...........................................................................................24 1 Map of Egypt. Late Predynastic Period-Early Dynastic (Grimal, 1994) Chronology of Predynastic period, Thinite period and Old Kingdom (from the appendix of Grimal’s book, 1994, p 389) 4500-3150 BC Predynastic period. 4500-4000 BC Badarian period 4000-3500 BC Naqada I (Amratian) 3500-3300 BC Naqada II (Gerzean A) 3300-3150 BC Naqada III (Gerzean B) 3150-2700 BC Thinite period 3150-2925 BC Dynasty 1 3150-2925 BC Narmer, Menes 3125-3100 BC Aha 3100-3055 BC -

Reading G Uide

1 Reading Guide Introduction Pharaonic Lives (most items are on map on page 10) Bodies of Water Major Regions Royal Cities Gulf of Suez Faiyum Oasis Akhetaten Sea The Levant Alexandria Nile River Libya Avaris Nile cataracts* Lower Egypt Giza Nile Delta Nubia Herakleopolis Magna Red Sea Palestine Hierakonpolis Punt Kerma *Cataracts shown as lines Sinai Memphis across Nile River Syria Sais Upper Egypt Tanis Thebes 2 Chapter 1 Pharaonic Kingship: Evolution & Ideology Myths Time Periods Significant Artifacts Predynastic Origins of Kingship: Naqada Naqada I The Narmer Palette Period Naqada II The Scorpion Macehead Writing History of Maqada III Pharaohs Old Kingdom Significant Buildings Ideology & Insignia of Middle Kingdom Kingship New Kingdom Tombs at Abydos King’s Divinity Mythology Royal Insignia Royal Names & Titles The Book of the Heavenly Atef Crown The Birth Name Cow Blue Crown (Khepresh) The Golden Horus Name The Contending of Horus Diadem (Seshed) The Horus Name & Seth Double Crown (Pa- The Nesu-Bity Name Death & Resurrection of Sekhemty) The Two Ladies Name Osiris Nemes Headdress Red Crown (Desheret) Hem Deities White Crown (Hedjet) Per-aa (The Great House) The Son of Re Horus Bull’s tail Isis Crook Osiris False beard Maat Flail Nut Rearing cobra (uraeus) Re Seth Vocabulary Divine Forces demi-god heka (divine magic) Good God (netjer netjer) hu (divine utterance) Great God (netjer aa) isfet (chaos) ka-spirit (divine energy) maat (divine order) Other Topics Ramesses II making sia (Divine knowledge) an offering to Ra Kings’ power -

UCLA Encyclopedia of Egyptology

UCLA UCLA Encyclopedia of Egyptology Title Mace Permalink https://escholarship.org/uc/item/497168cs Journal UCLA Encyclopedia of Egyptology, 1(1) Author Stevenson, Alice Publication Date 2008-09-15 Peer reviewed eScholarship.org Powered by the California Digital Library University of California MACE الصولجان Alice Stevenson EDITORS WILLEKE WENDRICH Editor-in-Chief Area Editor Material Culture, Art, and Architecture University of California, Los Angeles JACCO DIELEMAN Editor University of California, Los Angeles ELIZABETH FROOD Editor University of Oxford JOHN BAINES Senior Editorial Consultant University of Oxford Short Citation: Stevenson, 2008, Mace. UEE. Full Citation: Stevenson, Alice, 2008, Mace. In Willeke Wendrich (ed.), UCLA Encyclopedia of Egyptology, Los Angeles, http://digital2.library.ucla.edu/viewItem.do?ark=21198/zz000sn03x 1070 Version 1, September 2008 http://digital2.library.ucla.edu/viewItem.do?ark=21198/zz000sn03x MACE الصولجان Alice Stevenson Keule Massue The mace, a club-like weapon attested in ancient Egypt from the Predynastic Period onward, played both functional and ceremonial roles, although more strongly the latter. By the First Dynasty it had become intimately associated with the power of the king, and the archetypal scene of the pharaoh wielding a mace endured from this time on in temple iconography until the Roman Period. الصولجان ‘ سﻻح يشبه عصا غليظة عند طرفھا ‘ كان معروفاً فى مصر القديمة منذ عصر ما قبل اﻷسرات ولعب أحياناً دوراً وظيفياً وغالباً دوراً تشريفياً فى المراسم. في عصر اﻷسرة اﻷولى اصبح مرتبطاً على ٍنحو حميم بقوة الملك والنموذج اﻷصلي لمشھد الفرعون ممسك بالصولجان بدأ آنذاك بالمعابد وإستمر حتى العصر الروماني. he mace is a club-like weapon with that became prevalent in dynastic Egypt. -

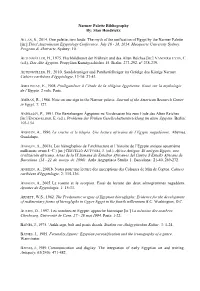

Stan Hendrickx ALLAN, S., 2014. One Palette, Two Lands

Narmer Palette Bibliography By: Stan Hendrickx ALLAN, S., 2014. One palette, two lands: The myth of the unification of Egypt by the Narmer Palette [in:] Third Australasian Egyptology Conference. July 16 - 18, 2014. Macquarie University Sydney. Program & Abstracts. Sydney: 10. ALTENMÜLLER, H., 1975. Flachbildkunst der Frühzeit und des Alten Reiches [in:] VANDERSLEYEN, C. (ed.), Das Alte Ägypten. Propyläen Kunstgeschichte 15. Berlin: 273-292, n° 238-239. ALTENMÜLLER, H., 2010. Sandalenträger und Pantherfellträger im Gefolge des Königs Narmer. Cahiers caribéens d'égyptologie, 13-14: 27-43. AMELINEAU, E., 1908. Prolégomènes à l’étude de la réligion égyptienne. Essai sur la mythologie de l’Egypte. 2 vols. Paris. AMIRAN, R., 1968. Note on one sign in the Narmer palette. Journal of the American Research Center in Egypt, 7: 127. ANDRASSY, P., 1991. Die Beziehungen Ägyptens zu Vorderasien bis zum Ende des Alten Reiches [in:] ENDESFELDER, E. (ed.), Probleme der Frühen Gesellschaftsentwicklung im alten Ägypten. Berlin: 103-154. ANSELIN, A., 1996. La cruche et le tilapia. Une lecture africaine de l’Egypte nagadéenne. Abymes, Guadalupe. ANSELIN, A., 2001a. Les hiéroglyphes de l’architecture et l’histoire de l’Egypte antique (quatrième millénaire avant J.-C.) [in:] CERVELLÓ AUTUORI, J. (ed.), Africa Antigua. El antiguo Egipto, una civilización africana. Actas de la IX Semana de Estudios Africanos del Centre d’Estudis Africans de Barcelona (18 - 22 de marzo de 1996). Aula Aegyptiaca Studia 1. Barcelona: 21-40, 269-272. ANSELIN, A., 2001b. Notes pour une lecture des inscriptions des Colosses de Min de Coptos. Cahiers caribéens d'égyptologie, 2: 115-136. ANSELIN, A., 2005. -

Images of Power

IMAGES OF POWER: PREDYNASTIC and OLD KINGDOM EGYPT: FOCUS (Egyptian Sculpture of Predynastic and Old Kingdom Egypt) ONLINE ASSIGNMENT: http://smarthisto ry.khanacademy .org/palette-of- king- narmer.html TITLE or DESIGNATION: Palette of Narmer CULTURE or ART HISTORICAL PERIOD: Predynastic Egyptian DATE: c. 3100- 3000 B.C.E. MEDIUM: slate TITLE or DESIGNATION: Seated Statue of Khafre, from his mortuary temple at Gizeh CULTURE or ART HISTORICAL PERIOD: Old Kingdom Egyptian DATE: c. 2575-2525 B.C.E. MEDIUM: diorite ONLINE ASSIGNMENT: https://www.khanacademy.org/human ities/ancient-art-civilizations/egypt- art/predynastic-old-kingdom/a/king- menkaure-mycerinus-and-queen TITLE or DESIGNATION: King Menkaure and his queen (possibly Khamerernebty) CULTURE or ART HISTORICAL PERIOD: Old Kingdom Egyptian DATE: c. 2490-2472 B.C.E. MEDIUM: slate ONLINE ASSIGNMENT: https://www.khanacademy. org/humanities/ancient- art-civilizations/egypt- art/predynastic-old- kingdom/v/the-seated- scribe-c-2620-2500-b-c-e TITLE or DESIGNATION: Seated Scribe from Saqqara CULTURE or ART HISTORICAL PERIOD: Old Kingdom Egyptian DATE: c. 2450-2325 B.C.E. MEDIUM: painted limestone with inlaid eyes of rock crystal, calcite, and magnesite IMAGES OF POWER: PREDYNASTIC and OLD KINGDOM EGYPT: SELECTED TEXT (Egyptian Sculpture of Predynastic and Old Kingdom Egypt) The Palette of King Narmer, c. 3100-3000 BCE, slate Dating from about the 31st century BCE, this “palette” contains some of the earliest hieroglyphic inscriptions ever found. It is thought by some to depict the unification of Upper and Lower Egypt under the king Narmer. On one side, the king is depicted with the bulbous White crown of Upper (southern) Egypt, and the other side depicts the king wearing the level Red Crown of Lower (northern) Egypt. -

Before the Pyramids Oi.Uchicago.Edu

oi.uchicago.edu Before the pyramids oi.uchicago.edu before the pyramids baked clay, squat, round-bottomed, ledge rim jar. 12.3 x 14.9 cm. Naqada iiC. oim e26239 (photo by anna ressman) 2 oi.uchicago.edu Before the pyramids the origins of egyptian civilization edited by emily teeter oriental institute museum puBlications 33 the oriental institute of the university of chicago oi.uchicago.edu Library of Congress Control Number: 2011922920 ISBN-10: 1-885923-82-1 ISBN-13: 978-1-885923-82-0 © 2011 by The University of Chicago. All rights reserved. Published 2011. Printed in the United States of America. The Oriental Institute, Chicago This volume has been published in conjunction with the exhibition Before the Pyramids: The Origins of Egyptian Civilization March 28–December 31, 2011 Oriental Institute Museum Publications 33 Series Editors Leslie Schramer and Thomas G. Urban Rebecca Cain and Michael Lavoie assisted in the production of this volume. Published by The Oriental Institute of the University of Chicago 1155 East 58th Street Chicago, Illinois 60637 USA oi.uchicago.edu For Tom and Linda Illustration Credits Front cover illustration: Painted vessel (Catalog No. 2). Cover design by Brian Zimerle Catalog Nos. 1–79, 82–129: Photos by Anna Ressman Catalog Nos. 80–81: Courtesy of the Ashmolean Museum, Oxford Printed by M&G Graphics, Chicago, Illinois. The paper used in this publication meets the minimum requirements of American National Standard for Information Service — Permanence of Paper for Printed Library Materials, ANSI Z39.48-1984 ∞ oi.uchicago.edu book title TABLE OF CONTENTS Foreword. Gil J. -

Making, Remaking and Unmaking Early 'Writing'

“It Is Written”?: Making, remaking and unmaking early ‘writing’ in the lower Nile Valley Kathryn E. Piquette Freie Universität Berlin Introduction Analysis and interpretation of inscribed objects often focus on their written meanings and thus their status as products of completed action. Attention is less commonly directed to the ways in which past actors intermingled and transformed material substances via particular tools and embodied behaviours — the material practices which give rise to graphical expres- sion and anchor subsequent acts of symbolic meaning (re-)construction. Building on research into the materiality of early writing and related image making (see Piquette 2007; 2008), this chapter focusses on one aspect of written object ‘life histories’ — the processes of remaking and unmaking. I explore below the dynamic unfolding and reformulation of ‘writing’ and related imagery as artefact within the context of a selection of early inscribed objects from the lower Nile Valley (Figure 1). The more portable writing surfaces include over 4000 objects, including small labels, ceramic and stone vessels, stelae, seals and seal impressions, imple- ments, and personal items (Regulski 2010: 6, 242). The geographically- and temporally-related marks on fixed stone surfaces (variously referred to as ‘petroglyphs’, ‘rock art’, ‘rock inscrip- tions’ or ‘graffiti’, e.g. Redford and Redford 1989; Storemyr 2009) also constitute a crucial dataset for questions of early writing and image-making practices in north-east Africa, but fall outside the scope of this chapter. For its basis, this inquiry examines comparatively three inscribed find types: small perforated plaques or ‘labels’ of bone, ivory and wood; stone ves- sels; and stone stelae. -

EXPERIENCING POWER, GENERATING AUTHORITY Cosmos, Politics, and the Ideology of Kingship in Ancient Egypt and Mesopotamia

EXPERIENCING POWER, GENERATING AUTHORITY Cosmos, Politics, and the Ideology of Kingship in Ancient Egypt and Mesopotamia edited by Jane A. Hill, Philip Jones, and Antonio J. Morales University of Pennsylvania Museum of Archaeology and Anthropology Philadelphia Library of Congress Cataloging-in-Publication Data © 2013 by the University of Pennsylvania Museum of Archaeology and Anthropology Philadelphia, PA All rights reserved. Published 2013 Published for the University of Pennsylvania Museum of Archaeology and Anthropology by the University of Pennsylvania Press. Printed in the United States of America on acid-free paper. 1 Propaganda and Performance at the Dawn of the State ellen f. morris ccording to pharaonic ideology, the maintenance of cosmic, political, Aand natural order was unthinkable without the king, who served as the crucial lynchpin that held together not only Upper and Lower Egypt, but also the disparate worlds of gods and men. Because of his efforts, soci- ety functioned smoothly and the Nile floods brought forth abundance. This ideology, held as gospel for millennia, was concocted. The king had no su- pernatural power to influence the Nile’s flood and the institution of divine kingship was made to be able to function with only a child or a senile old man at its helm. This chapter focuses on five foundational tenets of phara- onic ideology, observable in the earliest monuments of protodynastic kings, and examines how these tenets were transformed into accepted truths via the power of repeated theatrical performance. Careful choreography and stagecraft drew upon scent, pose, metaphor, abject foils, and numerous other ploys to naturalize a political order that had nothing natural about it. -

The Narmer Catalog

The Narmer Catalog Source No. Bibliography 5031 ADAMS, B.G., 1974. Ancient Hierakonpolis. Warminster. p. 3; 0082 ADAMS, B.G., 1995. Ancient Nekhen: Garstang in the city of Hierakonpolis. Surrey. pp. 123-24; p. 124. 0078 ADAMS, B.G., 1995. Ancient Nekhen: Garstang in the city of Hierakonpolis. Surrey. p. 48; 5026 ADAMS, B.G., 1995. Ancient Nekhen: Garstang in the city of Hierakonpolis. Surrey. p. 51; 5027 ADAMS, B.G., 1995. Ancient Nekhen: Garstang in the city of Hierakonpolis. Surrey. pp. 48-49; 5026 ADAMS, B.G., 2000. Excavations in the Locality 6 cemetery at Hierakonpolis 1979-1985. British Archaeological Reports International Series 903. Oxford. p. 20; pl. Vb. 0125 Ägyptisches Museum und Papyrussammlung ( Berlin ) : http://www.smb-digital. de/eMuseumPlus? service=ExternalInterface&module=collection&objectId=607035&viewType=detailView 22607. 4746 Alejandro Jiménez-Serrano, personal communication, 2015. 0116 Alejandro Jiménez-Serrano, personal communication, 2017. 0110 Alejandro Jiménez-Serrano, personal communication, 2017. 0117 Alejandro Jiménez-Serrano, personal communication, 2017. 0100 AMÉLINEAU, É. 1899. Les nouvelles fouilles d'Abydos (1895-1896): compte rendu in extenso des fouilles, description des monuments et objets découverts (Band 1). Paris. pp. 299-300; pl. XLII (left, 2nd one down). 0175 AMIRAN, R., 1970. A new acquisition – an Egyptian First Dynasty jar. The Israel Museum News, 4, 2: 88-94. pp. 88-94; p. 88, pl. 1; p. 93, pl. 2. 0123 AMIRAN, R., 1974. An Egyptian jar fragment with the name of Narmer from Arad. Israel Exploration Journal, 24(1): 4-12. pp. 4-12; p. 5, fig. 1.1; pl. 1. 0123 AMIRAN, R., 1976. -

Major Geological Fissure Through Prehistoric Lion Monument at Giza Inspired Split Lion Hieroglyphs and Ancient Egypt’S Creation Myth

Archaeological Discovery, 2019, 7, 211-256 https://www.scirp.org/journal/ad ISSN Online: 2331-1967 ISSN Print: 2331-1959 Major Geological Fissure through Prehistoric Lion Monument at Giza Inspired Split Lion Hieroglyphs and Ancient Egypt’s Creation Myth Manu Seyfzadeh, Robert M. Schoch Institute for the Study of the Origins of Civilization, College of General Studies, Boston University, Boston, MA, USA How to cite this paper: Seyfzadeh, M., & Abstract Schoch, R. M. (2019). Major Geological Fissure through Prehistoric Lion Monu- In search of textual references to a monumental lion at Giza predating the ment at Giza Inspired Split Lion Hierog- Old Kingdom, we focused our investigation on the earliest use of three an- lyphs and Ancient Egypt’s Creation Myth. cient Egyptian hieroglyphs depicting the frontal and caudal halves of a lion Archaeological Discovery, 7, 211-256. and a fissure-like symbol. These symbols first appear in Egypt’s proto- and https://doi.org/10.4236/ad.2019.74011 early dynastic era and form part of Egypt’s earliest known set of written lan- Received: August 5, 2019 guage symbols. During the First Dynasty, these symbols were both carved in- Accepted: August 30, 2019 to ivory tags and painted onto jars to designate the quality of oil shipped as Published: September 2, 2019 grave goods to both royal and private tombs. The same iconography and symbols appear in the creation story recorded on the frieze and upper register Copyright © 2019 by author(s) and Scientific Research Publishing Inc. of the Edfu Temple’s enclosure wall, where the frontal and caudal animal This work is licensed under the Creative parts are used to name two of seven personified creation words, the so-called Commons Attribution International ḏ3jsw1, uttered during the act of creating the world from the primordial flood License (CC BY 4.0). -

Pschent Headdress.Indd

PSCHENT HEADDRESS Age Range: Any Description: The Pschent represented power of both the upper and the lower parts of Egypt. Create your own and wear it like the Kings of Egypt did! Historic Context: The Pschent Headdress represents the unification of upper and lower Egypt. It was also called the “shmty” which means “The Two Powerful Ones.” The Pschent Headdress is a very little combination of the hedjet crown, or the white crown of Upper Egypt and the deshret, the red crown of Lower Egypt. The famous Narmer Palette depicts the pharaoh Menes unifying Lower and Upper Egypt, however, it was more of a conquest that took place and Upper Egypt won. It is said the Menes invented the double crown known as the Pschent Headdress, but the first pharaoh to wear the crown was Djet. The god’s Horus and Atum are also depicted wearing the Pschent Headdress. Time: 1 hour Materials Needed: plastic bottle, construction paper, scissors, tape/glue, white paint STEP ONE: CUT THE BOTTOM OF THE BOTTLE OUT. STEP TWO: PAINT THE BOTTLE WHITE, IT MAY TAKE A FEW COATS. SHOW US YOUR CREATION #RAFFMACSUSB STEP THREE: CUT A PIECE OF CONSTRUCTION PAPER VERTICALLY AND CREATE A CIRCULAR CROWN BASE. STEP FOUR: GET ANOTHER PIECE OF PAPER AND FOLD IT IN HALF. STEP FIVE: FOLD THE TWO TOP CORNERS IN UNTIL THEY REACH THE MIDDLE. SHOW US YOUR CREATION #RAFFMACSUSB STEP SIX: ATTACH BOTH OF THE PIECES TOGETHER. STEP SEVEN: FROM YOUR SCRAPS, CUT A PIECE OF PAPER THAT IS ABOUT AN INCH WIDE AND CURL IT UP ABOUT HALF WAY.