Jennnifer Camp Pbell, R Richard D Colb By, & R Rebeka Ah Shultz Colby

Total Page:16

File Type:pdf, Size:1020Kb

Load more

Recommended publications

-

Precio Maketa Punk-Oi! Oi! Core 24 ¡Sorprendete!

GRUPO NOMBRE DEL MATERIAL AÑO GENERO LUGAR ID ~ Precio Maketa Punk-Oi! Oi! Core 24 ¡Sorprendete! La Opera De Los Pobres 2003 Punk Rock España 37 100% Pure British Oi! Música Punk HC Cd 1 Punk Rock, HC Varios 6 100% Pure British Oi! Música Punk HC Cd 2 Punk Rock, HC Varios 6 100% Pure British Oi! Música Punk HC Cd 1 Punk Rock, HC Varios 10 100% Pure British Oi! Música Punk HC Cd 2 Punk Rock, HC Varios 10 1ª Komunion 1ª Komunion 1991 Punk Rock Castellón 26 2 Minutos Valentin Alsina Punk Rock Argentina 1 2 Minutos Postal 97 1997 Punk Rock Argentina 1 2 Minutos Volvió la alegría vieja Punk Rock Argentina 2 2 Minutos Valentin Alsina Punk rock Argentina 12 2 Minutos 8 rolas Punk Rock Argentina 13 2 Minutos Postal ´97 1997 Punk Rock Argentina 32 2 Minutos Valentin Alsina Punk Rock Argentina 32 2 Minutos Volvio la alegria vieja 1995 Punk Rock Argentina 32 2 Minutos Dos Minutos De Advertencia 1999 Punk Rock Argentina 33 2 Minutos Novedades 1999 Punk Rock Argentina 33 2 Minutos Superocho 2004 Punk Rock Argentina 47 2Tone Club Where Going Ska Francia 37 2Tone Club Now Is The Time!! Ska Francia 37 37 hostias Cantando basjo la lluvia ácida Punk Rock Madrid, España 26 4 Skins The best of the 4 skins Punk Rock 27 4 Vientos Sentimental Rocksteady Rocksteady 23 5 Years Of Oi! Sweat & Beers! 5 Years Of Oi! Sweat & Beers! Rock 32 5MDR Stato Di Allerta 2008 Punk Rock Italia 46 7 Seconds The Crew 1984 Punk Rock, HC USA 27 7 Seconds Walk Together, Rock Together 1985 Punk Rock, HC USA 27 7 Seconds New Wind 1986 Punk Rock, HC USA 27 7 Seconds Live! One Plus One -

24 Frames SF Tube Talk Reanimation in This Issue Movie News TV News & Previews Anime Reviews by Lee Whiteside by Lee Whiteside News & Reviews

Volume 12, Issue 4 August/September ConNotations 2002 The Bi-Monthly Science Fiction, Fantasy & Convention Newszine of the Central Arizona Speculative Fiction Society 24 Frames SF Tube Talk ReAnimation In This Issue Movie News TV News & Previews Anime Reviews By Lee Whiteside By Lee Whiteside News & Reviews The next couple of months is pretty slim This issue, we’ve got some summer ***** Sailor Moon Super S: SF Tube Talk 1 on genre movie releases. Look for success stories to talk about plus some Pegasus Collection II 24 Frames 1 Dreamworks to put Ice Age back in the more previews of new stuff coming this ***** Sherlock Hound Case File II ReAnimation 1 theatre with some extra footage in advance fall. **** Justice League FYI 2 of the home video release and Disney’s The big news of the summer so far is **** Batman: The Animated Series - Beauty & The Beast may show up in the success of The Dead Zone. Its debut The Legend Begins CASFS Business Report 2 regular theatre sometime this month. on USA Network on June 16th set **** ZOIDS : The Battle Begins Gamers Corner 3 September is a really dry genre month, with records for the debut of a cable series, **** ZOIDS: The High-Speed Battle ConClusion 4 only the action flick Ballistic: Eck Vs *** Power Rangers Time Force: Videophile 8 Sever on the schedules as of press time. Dawn Of Destiny Musty Tomes 15 *** Power Rangers Time Force: The End Of Time In Our Book (Book Reviews) 16 Sailor Moon Super S: Special Feature Pegasus Collection II Hary Potter and the Path to the DVD Pioneer, 140 mins, 13+ Secrets DVD $29.98 by Shane Shellenbarger 7 In Sailor Moon Super S, Hawkeye, Convention & Fandom Tigereye, and Fisheye tried to find Pegasus by looking into peoples dreams. -

Jacobs Ceases Quest for Tenure White to Retire As Trinity Dean Off-Campus

ANNUAL SEND-HOME EDITION It's the Olympics, y'all!!! Take a iook at an insider's view ofthe impact that The Centennial Games are THE CHRONICLE having on Atlanta. See Currents. WEDNESDAY. JULY 24, 1996 DUKE UNIVERSITY DURHAM, NORTH CAROLINA Jacobs ceases quest for tenure By MARSHA JOHNSON appeal was primarily based reconsidered. After this ap Timothy Jacobs, assistant on his conclusion that the na peal was denied, Jacobs ap professor of civil and envi ture of the process would pealed to the ombudsman in ronmental engineering, said prevent his concerns from March and was again denied. he will not appeal to the Fac truly being considered. "It Members of Jacobs' de ulty Hearing Committee and looked like the odds are partment expressed their re will therefore end stacked against grets that he will no longer his fight for me," he said. be working at the University. tenure. He will An appeal to the "His leaving is to the detri begin a job Aug. 1 FHC would have ment of our department and in the research de been Jacobs' next our students," said Eric Pas, partment of Sabre step in the tenure associate professor of civil Decision Technolo appeals process, and environmental engineer gy, a consulting which began in ing. firm in the Dallas- February when Criticism has surrounded Fort Worth area. Provost John Stro the decision, from both stu "We're excited hbehn denied Ja dents—who organized a rally about it," he said of Timothy Jacobs cobs' December March 28 in protest of both he and his family. -

Speed Kills / Hannibal Production in Association with Saban Films, the Pimienta Film Company and Blue Rider Pictures

HANNIBAL CLASSICS PRESENTS A SPEED KILLS / HANNIBAL PRODUCTION IN ASSOCIATION WITH SABAN FILMS, THE PIMIENTA FILM COMPANY AND BLUE RIDER PICTURES JOHN TRAVOLTA SPEED KILLS KATHERYN WINNICK JENNIFER ESPOSITO MICHAEL WESTON JORDI MOLLA AMAURY NOLASCO MATTHEW MODINE With James Remar And Kellan Lutz Directed by Jodi Scurfield Story by Paul Castro and David Aaron Cohen & John Luessenhop Screenplay by David Aaron Cohen & John Luessenhop Based upon the book “Speed Kills” by Arthur J. Harris Produced by RICHARD RIONDA DEL CASTRO, pga LUILLO RUIZ OSCAR GENERALE Executive Producers PATRICIA EBERLE RENE BESSON CAM CANNON MOSHE DIAMANT LUIS A. REIFKOHL WALTER JOSTEN ALASTAIR BURLINGHAM CHARLIE DOMBECK WAYNE MARC GODFREY ROBERT JONES ANSON DOWNES LINDA FAVILA LINDSEY ROTH FAROUK HADEF JOE LEMMON MARTIN J. BARAB WILLIAM V. BROMILEY JR NESS SABAN SHANAN BECKER JAMAL SANNAN VLADIMIRE FERNANDES CLAITON FERNANDES EUZEBIO MUNHOZ JR. BALAN MELARKODE RANDALL EMMETT GEORGE FURLA GRACE COLLINS GUY GRIFFITHE ROBERT A. FERRETTI SILVIO SARDI “SPEED KILLS” SYNOPSIS When he is forced to suddenly retire from the construction business in the early 1960s, Ben Aronoff immediately leaves the harsh winters of New Jersey behind and settles his family in sunny Miami Beach, Florida. Once there, he falls in love with the intense sport of off-shore powerboat racing. He not only races boats and wins multiple championship, he builds the boats and sells them to high-powered clientele. But his long-established mob ties catch up with him when Meyer Lansky forces him to build boats for his drug-running operations. Ben lives a double life, rubbing shoulders with kings and politicians while at the same time laundering money for the mob through his legitimate business. -

Zagadnienia Informacji Naukowej Nr 1

Zagadnienia informacji naukowej Studia informacyjne issues in information science Information Studies Vol. 54 2016 No. 1(107) p-ISSN 0324-8194 e-ISSN 2392-2648 Warszawa 2016 Issues In InformatIon scIence – InformatIon studIes The core purpose of this journal is to provide a forum for the dissemination of scientific papers and re- search results in the field of information science and other disciplines which analyze social and technolog- ical aspects of various information-related activities performed by contemporary communities. Moreover, the journal is to disseminate critical reviews and summaries of new publications in the field of information science and reports from important conferences discussing contemporary information problems. In addition to that, after fifty yearsIssues in Information Science (ZIN) becomes bilingual to reach foreign readers – papers are available either in Polish or English. The reconstructed journal is published with slightly extended titleIssues in Information Science – In- formation Studies (ZIN – Information Studies) – the subtitle emphasizes the interdisciplinary nature of its subject profile covering a broad spectrum of issues studied by various academic disciplines and professional activity domains related to access to resources of recorded information and knowledge and the use of these resources by contemporary man and society. Other subjects to be covered by ZIN involve: 1) theoretical ponderings on the practice of information-related activities performed by various communities, 2) the re- sults of -

Elp -Discography

ELP Discography ELP -DISCOGRAPHY- (1970 - 2002) NOTE: THIS DISCOGRAPHY and SONG LIST is BASED ON MY OWN COLLECTION, plus LATEST INFO FROM WEBSITES (inc. DISCOGRAPHY ORIGINALLY PUBLISHED by ELP DIGEST) and “THE SHOW THAT NEVER ENDS…” A MUSICAL BIOGRAPHY (by FORRESTER, HANSON & ASKEW) DICOGRAPHY covers ALL KNOWN ALBUMS, SINGLES and VIDEOS by EMERSON, LAKE and PALMER (either TOGETHER or INDIVIDUALLY), ordered CHRONOLOGICALLY between the Years 1970 to 2002 Clive ffitch (a fan!) Logo/Link to Official ELP Global Web Site SUMMARY: ALL ALBUMS / CDs (inc. ELPowell and Three) ALL SINGLES + ALBUMS - KEITH EMERSON + ALBUMS - GREG LAKE + ALBUMS - CARL PALMER + ALL ELP VIDEOS + THE BOOK! Page 1 ELP Discography ELP - THE COLLECTION TITLES: ELP ALBUMS / CDs (inc. ELPowell and Three): ELP SINGLES (inc. Individuals): Vinyl CD Vinyl CD (excluding other Promo’s) [ ] [ ] 1. Emerson Lake and Palmer [ ] 1. Lucky Man / Knife Edge [ ] [ ] 2. Tarkus [ ] 2. Take a Pebble / Lucky Man [ ] [ ] 3. Pictures at an Exhibition [ ] 3. Stones of Years / A Time... [ ] [ ] 4. Trilogy [ ] 4. Nutrocker / Great Gates... [ ] [ ] 5. Brain Salad Surgery [ ] 5. From the Beginning / Living... [ ] [ ] 6. Welcome Back My Friends [ ] 6. Brain Salad (NME Floppie) [ ] [ ] 7. Works Vol.I [ ] 7. Jerusalem / Apple Blossom... [ ] [ ] 8. Works Vol.II [ ] 8. Still... You Turn Me On / Brain [ ] [ ] 9. Love Beach [ ] [ ] 9. I Believe in Father Xmas (L) [ ]. 10. In Concert (re-issued as Works Live) [ ] 10. Honky Tonk Train Blues (E) [ ] [ ] 11. The Best of ELP (1980) [ ] [ ] 11. Fanfare for Common Man [ ] [ ] 12. Emerson Lake and Powell (ELPo) [ ] 12. C’est La Vie (L) [ ] [ ] 13. To the Power of Three (Three) [ ] 13. All I Want is You / Tiger.. -

Black Sabbath the Complete Guide

Black Sabbath The Complete Guide PDF generated using the open source mwlib toolkit. See http://code.pediapress.com/ for more information. PDF generated at: Mon, 17 May 2010 12:17:46 UTC Contents Articles Overview 1 Black Sabbath 1 The members 23 List of Black Sabbath band members 23 Vinny Appice 29 Don Arden 32 Bev Bevan 37 Mike Bordin 39 Jo Burt 43 Geezer Butler 44 Terry Chimes 47 Gordon Copley 49 Bob Daisley 50 Ronnie James Dio 54 Jeff Fenholt 59 Ian Gillan 62 Ray Gillen 70 Glenn Hughes 72 Tony Iommi 78 Tony Martin 87 Neil Murray 90 Geoff Nicholls 97 Ozzy Osbourne 99 Cozy Powell 111 Bobby Rondinelli 118 Eric Singer 120 Dave Spitz 124 Adam Wakeman 125 Dave Walker 127 Bill Ward 132 Related bands 135 Heaven & Hell 135 Mythology 140 Discography 141 Black Sabbath discography 141 Studio albums 149 Black Sabbath 149 Paranoid 153 Master of Reality 157 Black Sabbath Vol. 4 162 Sabbath Bloody Sabbath 167 Sabotage 171 Technical Ecstasy 175 Never Say Die! 178 Heaven and Hell 181 Mob Rules 186 Born Again 190 Seventh Star 194 The Eternal Idol 197 Headless Cross 200 Tyr 203 Dehumanizer 206 Cross Purposes 210 Forbidden 212 Live Albums 214 Live Evil 214 Cross Purposes Live 218 Reunion 220 Past Lives 223 Live at Hammersmith Odeon 225 Compilations and re-releases 227 We Sold Our Soul for Rock 'n' Roll 227 The Sabbath Stones 230 Symptom of the Universe: The Original Black Sabbath 1970–1978 232 Black Box: The Complete Original Black Sabbath 235 Greatest Hits 1970–1978 237 Black Sabbath: The Dio Years 239 The Rules of Hell 243 Other related albums 245 Live at Last 245 The Sabbath Collection 247 The Ozzy Osbourne Years 249 Nativity in Black 251 Under Wheels of Confusion 254 In These Black Days 256 The Best of Black Sabbath 258 Club Sonderauflage 262 Songs 263 Black Sabbath 263 Changes 265 Children of the Grave 267 Die Young 270 Dirty Women 272 Disturbing the Priest 273 Electric Funeral 274 Evil Woman 275 Fairies Wear Boots 276 Hand of Doom 277 Heaven and Hell 278 Into the Void 280 Iron Man 282 The Mob Rules 284 N. -

Asia Archiva 1 & 2 Mp3, Flac

Asia Archiva 1 & 2 mp3, flac, wma DOWNLOAD LINKS (Clickable) Genre: Rock Album: Archiva 1 & 2 Country: Europe Released: 2005 Style: Prog Rock MP3 version RAR size: 1785 mb FLAC version RAR size: 1803 mb WMA version RAR size: 1163 mb Rating: 4.6 Votes: 717 Other Formats: WMA AC3 MP2 VOX MP1 DTS VQF Tracklist Archiva 1 1-1 Heart Of Gold 1-2 Tears 1-3 Fight Against The Tide 1-4 We Fall Apart 1-5 The Mariner's Dream 1-6 Boys From Diamond City 1-7 A.L.O. 1-8 Reality 1-9 I Can't Wait A Lifetime 1-10 Dusty Road 1-11 I Believe 1-12 Ginger Bonus Tracks: 1-13 Anytime (Edit) 1-14 Open Your Eyes (Acoustic) Archiva 2 2-1 Obsession 2-2 Moon Under The Water 2-3 Love Like The Video 2-4 Don't Come To Me 2-5 The Smoke That Thunders 2-6 Satellite Blues 2-7 Showdown 2-8 That Season 2-9 I Can't Tell These Walls 2-10 The Higher You Climb 2-11 Right To Cry 2-12 Armenia Bonus Tracks: 2-13 Little Rich Boy (Edit) 2-14 Turn It Around (Ethnic Mix) Companies, etc. Distributed By – SPV GmbH – SPV 48442 DCD Notes Issued with O-Card Barcode and Other Identifiers Barcode: 6 93723 48442 6 Other versions Category Artist Title (Format) Label Category Country Year Archiva 1 & 2 (2xCD, Comp, Sony Records SICP 20420-1 Asia SICP 20420-1 Japan 2012 Ltd, RM, Blu) Int'l Archiva 1 & 2 (2xCD, Comp, IOMCD 220 Asia Inside Out Music IOMCD 220 Russia 2005 S/Edition, Sli) Related Music albums to Archiva 1 & 2 by Asia Rock Aid Armenia - Smoke On The Water '90 Andru Donalds - Diamond Collection Baillie & The Boys - Turn The Tide David Cassidy - The Higher They Climb - The Harder They Fall Ax7is feat. -

Movieguide.Pdf

Movies Without Nudity A guide to nudity in 8,345 movies From www.movieswithoutnudity.com Red - Contains Nudity Movies I Own 300: Rise of an Empire (2014) A. I. - Artificial Intelligence (2001) A La Mala (aka Falling for Mala) (2014) A-X-L (2018) A.C.O.D. (2013) [Male rear nudity] Abandon (2002) The Abandoned (2007) Abe Lincoln in Illinois (1940) Abel's Field (2012) The Abolitionists (2016) Abominable (2019) Abominable (2020) About a Boy (2002) About Adam (2001) About Last Night (1986) About Last Night (2014) About Schmidt (2002) About Time (2013) Above and Beyond (2014) Above Suspicion (1995) Above the Rim (1994) Abraham (1994) [Full nudity of boys playing in water] The Absent-Minded Professor (1961) Absolute Power (1997) Absolutely Fabulous: The Movie (2016) An Acceptable Loss (2019) Accepted (2006) The Accountant (2016) Ace in the Hole (1951) Ace Ventura: When Nature Calls (1995) [male rear nudity] Achilles' Love (2000) Across the Moon (1995) Across the Universe (2007) Action Jackson (1988) Action Point (2018) Acts of Violence (2018) Ad Astra (2019) Adam (2009) Adam at 6 A.M. (1970) Adam Had Four Sons (1941) Adam Sandler's Eight Crazy Nights (2002) Adam's Apples (2007) Adam's Rib (1949) Adaptation (2002) The Addams Family (2019) Addams Family Values (1993) Addicted (2014) Addicted to Love (1997) [Depends on who you ask, but dark shadows obscure any nudity.] The Adjuster (1991) The Adjustment Bureau (2011) The Admiral: Roaring Currents (aka Myeong-ryang) (2014) Admission (2013) Adrenaline Rush (2002) Adrift (2018) Adult Beginners (2015) Adult Life Skills (2019) [Drawings of penises] Adventures in Dinosaur City (1992) Adventures of Baron Munchausen (1989) Adventures of Buckaroo Banzai Across the 8th Dimension (1984) The Adventures of Elmo In Grouchland (1999) The Adventures of Huck Finn (1993) Adventures of Icabod and Mr. -

Library 3398 Songs, 7.2 Days, 12.30 GB

Library 3398 songs, 7.2 days, 12.30 GB Song Name Artist Album _Secret Agent - Guster Keep It Together – Celtic Twilight Loreena McKennitt '85 Radio Special Thank You They Might Be Giants Then: The Earlier Years (CD 1) 'Ama'ama Israel "IZ" Kamakawiwo'ole Facing Future 'Round Springfield (Medley) The Simpsons Songs In The Key Of Spring… 'S Wonderful Ella Fitzgerald The Best Of the Song Books 'Til Him The Producers "Badge OF Honor"- Jerry Goldsmith Jerry Goldsmith L.A. Confidential "Chief Wiggum, P.I." Main Title The Simpsons Go Simpsonic With The Sim… "Eye On Springfield" Theme The Simpsons Songs In The Key Of Spring… "Itchy & Scratchy" End Credits Theme The Simpsons Songs In The Key Of Spring… "Itchy & Scratchy" Main Title Theme The Simpsons Songs In The Key Of Spring… "Kamp Krusty" Theme Song The Simpsons Go Simpsonic With The Sim… "Krusty The Clown" Main Title The Simpsons Go Simpsonic With The Sim… "Oh, Streetcar!" (The Musical) The Simpsons Songs In The Key Of Spring… "Quimby" Campaign Commercial The Simpsons Go Simpsonic With The Sim… "Scorpio" End Credits The Simpsons Go Simpsonic With The Sim… "Simpsoncalifragilisticexpiala(Annoyed Grunt)Cio… The Simpsons Go Simpsonic With The Sim… "Skinner & The Superintendent" Theme The Simpsons Go Simpsonic With The Sim… "The Itchy & Scratchy & Poochie Show" Theme The Simpsons Go Simpsonic With The Sim… "The Love-Matic Grampa" Main Title The Simpsons Go Simpsonic With The Sim… "The Simpsons" End Credits Theme The Simpsons Go Simpsonic With The Sim… "The Simpsons" End Credits Theme (Jazz Quartet -

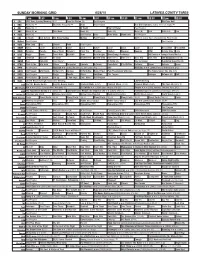

Sunday Morning Grid 6/28/15 Latimes.Com/Tv Times

SUNDAY MORNING GRID 6/28/15 LATIMES.COM/TV TIMES 7 am 7:30 8 am 8:30 9 am 9:30 10 am 10:30 11 am 11:30 12 pm 12:30 2 CBS CBS News Sunday Morning (N) Å Face the Nation (N) Paid Program PGA Tour Golf 4 NBC News (N) Å Meet the Press (N) Å News Paid Program Red Bull Signature Series From Las Vegas. Å 5 CW News (N) Å In Touch Hour Of Power Paid Program 7 ABC News (N) Å This Week News (N) News (N) News (N) Paid Vista L.A. Paid 9 KCAL News (N) Joel Osteen Hour Mike Webb Woodlands Paid Program 11 FOX In Touch Joel Osteen Fox News Sunday Midday Paid Program Golf U.S. Senior Open Championship, Final Round. 13 MyNet Paid Program Paid Program 18 KSCI Man Land Paid Church Faith Paid Program 22 KWHY Cosas Local Jesucristo Local Local Gebel Local Local Local Local RescueBot RescueBot 24 KVCR Painting Dowdle Joy of Paint Wyland’s Paint This Painting Kitchen Mexican Cooking BBQ Simply Ming Lidia 28 KCET Raggs Space Travel-Kids Biz Kid$ News Asia Insight BrainChange-Perlmutter 30 Days to a Younger Heart-Masley 30 ION Jeremiah Youssef In Touch Bucket-Dino Bucket-Dino Doki (TVY7) Doki (TVY7) Dive, Olly Dive, Olly The Bodyguard ›› (R) 34 KMEX Paid Conexión Paid Program Al Punto (N) Tras la Verdad República Deportiva (N) 40 KTBN Walk in the Win Walk Prince Carpenter Liberate In Touch PowerPoint It Is Written Pathway Super Kelinda Jesse 46 KFTR Paid Program Madison ›› (2001) Jim Caviezel, Jake Lloyd. -

Songs by Artist

Songs by Artist Title Title (Hed) Planet Earth 2 Live Crew Bartender We Want Some Pussy Blackout 2 Pistols Other Side She Got It +44 You Know Me When Your Heart Stops Beating 20 Fingers 10 Years Short Dick Man Beautiful 21 Demands Through The Iris Give Me A Minute Wasteland 3 Doors Down 10,000 Maniacs Away From The Sun Because The Night Be Like That Candy Everybody Wants Behind Those Eyes More Than This Better Life, The These Are The Days Citizen Soldier Trouble Me Duck & Run 100 Proof Aged In Soul Every Time You Go Somebody's Been Sleeping Here By Me 10CC Here Without You I'm Not In Love It's Not My Time Things We Do For Love, The Kryptonite 112 Landing In London Come See Me Let Me Be Myself Cupid Let Me Go Dance With Me Live For Today Hot & Wet Loser It's Over Now Road I'm On, The Na Na Na So I Need You Peaches & Cream Train Right Here For You When I'm Gone U Already Know When You're Young 12 Gauge 3 Of Hearts Dunkie Butt Arizona Rain 12 Stones Love Is Enough Far Away 30 Seconds To Mars Way I Fell, The Closer To The Edge We Are One Kill, The 1910 Fruitgum Co. Kings And Queens 1, 2, 3 Red Light This Is War Simon Says Up In The Air (Explicit) 2 Chainz Yesterday Birthday Song (Explicit) 311 I'm Different (Explicit) All Mixed Up Spend It Amber 2 Live Crew Beyond The Grey Sky Doo Wah Diddy Creatures (For A While) Me So Horny Don't Tread On Me Song List Generator® Printed 5/12/2021 Page 1 of 334 Licensed to Chris Avis Songs by Artist Title Title 311 4Him First Straw Sacred Hideaway Hey You Where There Is Faith I'll Be Here Awhile Who You Are Love Song 5 Stairsteps, The You Wouldn't Believe O-O-H Child 38 Special 50 Cent Back Where You Belong 21 Questions Caught Up In You Baby By Me Hold On Loosely Best Friend If I'd Been The One Candy Shop Rockin' Into The Night Disco Inferno Second Chance Hustler's Ambition Teacher, Teacher If I Can't Wild-Eyed Southern Boys In Da Club 3LW Just A Lil' Bit I Do (Wanna Get Close To You) Outlaw No More (Baby I'ma Do Right) Outta Control Playas Gon' Play Outta Control (Remix Version) 3OH!3 P.I.M.P.