SDC 9: the Frontispiece of De Re Anatomica

Total Page:16

File Type:pdf, Size:1020Kb

Load more

Recommended publications

-

Downloaded from Brill.Com10/10/2021 01:00:04AM Via Free Access

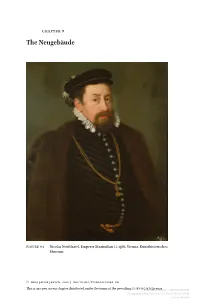

Chapter 9 The Neugebäude Figure 9.1 Nicolas Neufchatel, Emperor Maximilian ii, 1566, Vienna, Kunsthistorisches Museum. © dirk jacob jansen, ���9 | doi:�0.��63/9789004359499_0�� This is an open access chapter distributed under the terms of the prevailing cc-by-ncDirk-nd Jacob License. Jansen - 9789004359499 Downloaded from Brill.com10/10/2021 01:00:04AM via free access <UN> The Neugebäude 431 9.1 The Tomb of Ferdinand i and Anna in Prague; Licinio’s Paintings in Pressburg While in the act of drawing his proposals for the Munich Antiquarium, Strada appears to have been quite busy with other concerns. It is likely that these con- cerns included important commissions from his principal patron, the Emperor Maximilian ii [Fig. 9.1], who had been heard to express himself rather dis- satisfied with Strada’s continued occupation for his Bavarian brother-in-law. Already two year earlier, when Duke Albrecht had ‘borrowed’ Strada from the Emperor to travel to Italy to buy antiquities and works of art and to advise him on the accommodation for his collections, Maximilian had conceded this with some hesitation, telling the Duke that he could not easily spare Strada, whom he employed in several projects.1 Unfortunately Maximilian did not specify what projects these were. They certainly included the tomb for his parents in St Vitus’ Cathedral in Prague, that was to be executed by Alexander Colin, and for which Strada had been sent to Prague already in March of 1565 [Figs. 9.2–9.3]. As with his earlier in- volvement in the completion of the tomb of Maximilian -

The Evolution of Landscape in Venetian Painting, 1475-1525

THE EVOLUTION OF LANDSCAPE IN VENETIAN PAINTING, 1475-1525 by James Reynolds Jewitt BA in Art History, Hartwick College, 2006 BA in English, Hartwick College, 2006 MA, University of Pittsburgh, 2009 Submitted to the Graduate Faculty of The Dietrich School of Arts and Sciences in partial fulfillment of the requirements for the degree of Doctor of Philosophy University of Pittsburgh 2014 UNIVERSITY OF PITTSBURGH KENNETH P. DIETRICH SCHOOL OF ARTS AND SCIENCES This dissertation was presented by James Reynolds Jewitt It was defended on April 7, 2014 and approved by C. Drew Armstrong, Associate Professor, History of Art and Architecture Kirk Savage, Professor, History of Art and Architecture Jennifer Waldron, Associate Professor, Department of English Dissertation Advisor: Ann Sutherland Harris, Professor Emerita, History of Art and Architecture ii Copyright © by James Reynolds Jewitt 2014 iii THE EVOLUTION OF LANDSCAPE IN VENETIAN PAINTING, 1475-1525 James R. Jewitt, PhD University of Pittsburgh, 2014 Landscape painting assumed a new prominence in Venetian painting between the late fifteenth to early sixteenth century: this study aims to understand why and how this happened. It begins by redefining the conception of landscape in Renaissance Italy and then examines several ambitious easel paintings produced by major Venetian painters, beginning with Giovanni Bellini’s (c.1431- 36-1516) St. Francis in the Desert (c.1475), that give landscape a far more significant role than previously seen in comparable commissions by their peers, or even in their own work. After an introductory chapter reconsidering all previous hypotheses regarding Venetian painters’ reputations as accomplished landscape painters, it is divided into four chronologically arranged case study chapters. -

Profiling Women in Sixteenth-Century Italian

BEAUTY, POWER, PROPAGANDA, AND CELEBRATION: PROFILING WOMEN IN SIXTEENTH-CENTURY ITALIAN COMMEMORATIVE MEDALS by CHRISTINE CHIORIAN WOLKEN Submitted in partial fulfillment of the requirements For the degree of Doctor of Philosophy Dissertation Advisor: Dr. Edward Olszewski Department of Art History CASE WESTERN RESERVE UNIVERISTY August, 2012 CASE WESTERN RESERVE UNIVERSITY SCHOOL OF GRADUATE STUDIES We hereby approve the thesis/dissertation of Christine Chiorian Wolken _______________________________________________________ Doctor of Philosophy Candidate for the __________________________________________ degree*. Edward J. Olszewski (signed) _________________________________________________________ (Chair of the Committee) Catherine Scallen __________________________________________________________________ Jon Seydl __________________________________________________________________ Holly Witchey __________________________________________________________________ April 2, 2012 (date)_______________________ *We also certify that written approval has been obtained for any proprietary material contained therein. 1 To my children, Sofia, Juliet, and Edward 2 Table of Contents List of Images ……………………………………………………………………..….4 Acknowledgements……………………………………………………………...…..12 Abstract……………………………………………………………………………...15 Introduction…………………………………………………………………………16 Chapter 1: Situating Sixteenth-Century Medals of Women: the history, production techniques and stylistic developments in the medal………...44 Chapter 2: Expressing the Link between Beauty and -

Titian's Later Mythologies Author(S): W

Titian's Later Mythologies Author(s): W. R. Rearick Source: Artibus et Historiae, Vol. 17, No. 33 (1996), pp. 23-67 Published by: IRSA s.c. Stable URL: http://www.jstor.org/stable/1483551 . Accessed: 18/09/2011 17:13 Your use of the JSTOR archive indicates your acceptance of the Terms & Conditions of Use, available at . http://www.jstor.org/page/info/about/policies/terms.jsp JSTOR is a not-for-profit service that helps scholars, researchers, and students discover, use, and build upon a wide range of content in a trusted digital archive. We use information technology and tools to increase productivity and facilitate new forms of scholarship. For more information about JSTOR, please contact [email protected]. IRSA s.c. is collaborating with JSTOR to digitize, preserve and extend access to Artibus et Historiae. http://www.jstor.org W.R. REARICK Titian'sLater Mythologies I Worship of Venus (Madrid,Museo del Prado) in 1518-1519 when the great Assunta (Venice, Frari)was complete and in place. This Seen together, Titian's two major cycles of paintingsof mytho- was followed directlyby the Andrians (Madrid,Museo del Prado), logical subjects stand apart as one of the most significantand sem- and, after an interval, by the Bacchus and Ariadne (London, inal creations of the ItalianRenaissance. And yet, neither his earli- National Gallery) of 1522-1523.4 The sumptuous sensuality and er cycle nor the later series is without lingering problems that dynamic pictorial energy of these pictures dominated Bellini's continue to cloud their image as projected -

MARCH 2012 O.XI No

PQ-COVER 2012B_PQ-COVER MASTER-2007 24/01/2012 17:30 Page 1 P Q PRINT QUARTERLY MARCH 2012 Vol. XXIX No. 1 March 2012 VOLUME XXIX NUMBER 1 mar12PQHill-Stone_Layout 1 26/01/2012 16:23 Page 1 :DVVLO\.DQGLQVN\ .OHLQH:HOWHQFRPSOHWHVHWRIWZHOYHRULJLQDO SULQWV RQHIURPWKHVHWLOOXVWUDWHGDERYH ([KLELWLQJDW7()$)0DDVWULFKW 0DUFK 6WDQG PQ.MAR2012C_Layout 1 25/01/2012 17:12 Page 1 PrInT quarTerly volume XXIX number 1 march 2012 contents a Frontispiece for galileo’s Opere: Pietro anichini and Stefano della bella 3 Jaco ruTgerS engravings by Jacques Fornazeris with the arms of rené gros 13 henrIeTTe PommIer Représentant d’une grande nation: The Politics of an anglo-French aquatint 22 amanda lahIkaInen Shorter notices Some early States by martino rota 33 STePhen a. bergquIST Prints by gabriel huquier after oppenord’s decorated Ripa 37 Jean-FrançoIS bédard notes 44 catalogue and book reviews The Imagery of Proverbs 85 war Posters, Sustainable Posters 100 PeTer van der coelen and Street art Polish collectors of the nineteenth 88 Paul gough and Twentieth centuries Joan Snyder 103 waldemar deluga bIll norTh Samuel Palmer revisited 92 elizabeth Peyton 106 elIzabeTh e. barker wendy weITman Jules chéret 95 william kentridge 110 howard couTTS Paul coldwell modern british Posters 97 contemporary Printed art in Switzerland 112 marTIn hoPkInSon anTonIa neSSI PQ.MAR2012C_Layout 1 26/01/2012 13:49 Page 2 Editor Rhoda Eitel-Porter Administrator Sub-Editor Jocelyne Bancel Virginia Myers Editorial Board Clifford Ackley Pat Gilmour Giorgio Marini David Alexander Antony Griffiths Jean Michel Massing Judith Brodie Craig Hartley Nadine Orenstein Michael Bury Martin Hopkinson Peter Parshall Paul Coldwell Ralph Hyde Maxime Préaud Marzia Faietti David Kiehl Christian Rümelin Richard Field Fritz Koreny Michael Snodin Celina Fox David Landau Ellis Tinios David Freedberg Ger Luijten Henri Zerner Members of Print Quarterly Publications Registered Charity No. -

Dianakosslerovamlittthesis1988 Original C.Pdf

University of St Andrews Full metadata for this thesis is available in St Andrews Research Repository at: http://research-repository.st-andrews.ac.uk/ This thesis is protected by original copyright M.LITT. (ART GALLERY STUDIES) DISSERTATION AEGIDIDS SADELER'S ENGRAVINGS IN TM M OF SCOTLAND VOLUME I BY DIANA KOSSLEROVA DEPARTMENT OF ART HISTORY UNIVERSITY OF ST ANDREWS 1988 I, Diana Kosslerova, hereby certify that this thesis, which is approximately 24 000 words in length, has been written by me, that it is the record of work carried out by me and that it has not been submitted in any previous application for a higher degree. date.?.0. /V. ?... signature of candidate; I was admitted as a candidate for the degree of M.Litt. in October 1985 the higher study for which this is a record was carried out in the University of St. Andrews between October 1985 and April 1988. date... ????... signature of candidate. I hereby certify that the candidate has fulfilled the conditions of the Resolution and Regulations appropriate for the degree of in the University of St. Andrews and that the candidate is qualified to submit this thesis in application for that degree. datefV.Q. signature of supervisor, In submitting this thesis to the University of St. Andrews I understand that I am giving permission for it to be made available for use in accordance with the regulations of the University Library for the time being in force, subject to any copyright vested in the work not being affected thereby. I also understand that the title and abstract will be published, and that a copy of the work may be made and supplied to any bona fide library or research worker. -

THE ALLEGORY of DYNASTIC SUCCESSION on the FAÇADE of the PRAGUE BELVEDERE (1538–1550)* JAN BAŽANT Ferdinand I, Archduke of A

2017 ACTA UNIVERSITATIS CAROLINAE PAG. 269–282 PHILOLOGICA 2 / GRAECOLATINA PRAGENSIA THE ALLEGORY OF DYNASTIC SUCCESSION ON THE FAÇADE OF THE PRAGUE BELVEDERE (1538–1550)* JAN BAŽANT ABSTRACT The paper analyses a unique relief sculpture which decorates the Prague Belvedere built by Ferdinand I. It represents an old man on horseback passing the globe to a young man standing in front of him. The scene may be interpreted as the allegory of dynastic succession. The adjoining reliefs corroborate this hypothesis, on the left we find the coat of arms of the Bohemian Kingdom and on the right Andromeda liberated by Perseus, alter ego of Ferdinand I. Keywords: Ferdinand I; Renaissance art; relief sculpture; allegory; dynasty Ferdinand I, Archduke of Austria, King of Bohemia and Hungary and King of the Romans, started to build the Prague Belvedere in the Garden of Prague Castle in 1538. In 1550, the ground floor of this villa all ’ antica was completed (Bažant 2003a; Bažant 2005; Kalina, Koťátko 2011: 64–73). Column arcades on all four sides received rich sculptural decoration, which was the work of Paolo della Stella, who came to Prague from Genoa (Bažant 2003b; Bažant 2006: 99–218; Chlíbec 2011: 88–89; Bažant, Bažantová 2014: 68–219; Bažant 2016). In this paper I would like to present a new interpretation of the relief sculpture in the second spandrel of the north façade (Fig. 1). Its theme is unique. From the right, a bearded man in ancient armour arrives on horseback and holds some- thing in his outstretched right hand. A beardless young man is standing in front of the rider and holds the same object with his raised hands. -

Michael Willmann's Way to "The Heights of Art" and His Early Drawings

Originalveröffentlichung in: Bulletin of the National Gallery in Prague, 7-8 (1997-1998), S. 54-66 MICHAEL WILLMANN'S WAY TO "THE HEIGHTS OF ART" AND HIS EARLY DRAWINGS ANDRZEJ KOZIEL In his letter to Heinrich Snopek, the abbot of ing J having adopted the methods of Jacob Backer Cistercian monastery in Sedlec, Michael Willmann and also of Rembrandt and others", took up "very recommended to the abbot his former pupil and strict excercises" and carried them on diligently stepson Johann Christoph Liska as a guarantor of "days and nights".- a possible continuation of his work on the painting Unfortunately, among the extant drawings of The Martyrdom of the Cistercian and Carthusian Willmann, there are no works which can be un Monks in Sedlec in 1421 in the following words: "...er questionably recognised as made in the period of schon in seinem hesten Alter unci in flatten mehreres learning and journeys of the artist.' Thus we do not gesehen oder hegriffen alji ich in Hollandt thun ken- possess direct sources that will enable us to say nen. Er ist auch in Imentirung der HiJMorien sehr something more about the self-teaching of geistrich in der Ordinanzen die Bilder mil in und Willmann. However, I believe that the set of twenty durcheinander lebhaffl auch gluhenden Colleritten engravings by Josef Gregory after the drawings of Summit wafi einem rechten Kunstmahler nettig er in "des beruhmten Meister Willmann", made in a Hem gutte wissenschaft (dutch die gnad Gottes) he 1794-95 and published in Prague in 1805, informs griffen hat.".' Liska acquired the complete knowl us in an indirect way about the character of the edge of these principles of art education, which are youthful exercises of the artist.1 So far only one essential for the "right" painter - he could inge work from the copied drawings of Willmann has niously "invent" a visual equivalent for a literary been found - the scene Unfaithful Thomas before "story", moreover, he could wholly "arrange" both Christ [Fig. -

Bessenyei Jzsef

VERANCSICS ANTAL KORÁNAK HUMANISTA HÁLÓZATÁBAN VÁZLAT EGY KAPCSOLATI HÁLÓ MODELLEZÉSÉHEZ GÁL-MLAKÁR ZSÓFIA A magyar értelmiségi elit talán soha nem állt olyan közel egy nemzetközi eszmei irányzathoz és kapcsolódott olyan szorosan Európához, színvonalát és személyi kapcsolatait tekintve, mint az antikvitás iránt felélénkülő érdeklődés széleskörű elterjedésének idején, mely a reneszánsz meghatározó eszmei irányzataként jelent- kezett egész Európában. Az értelmiség útkeresése, életmodellje, informális és for- mális körei, kapcsolatai minden kornak meghatározó jelenségei az általuk nyújtott sajátos mentális modellen, tudomány- és társadalomszervező szerepükön és a vi- lágról alkotott változó elképzeléseiken, valamint azok megjelenítésén keresztül. Emellett pedig minden kor sajátos társadalmi viszonyai ismerhetők meg a fent említett réteg vizsgálatával, különösen, ami annak mobilitását, karrierstratégiáit és átalakulását, mozgását illeti. Az utóbbi időkben különösen is megszaporodó tanulmányok, komplex ku- tatások jelzik: többé nem csupán arra vagyunk kíváncsiak, hogy hogyan és mit alkottak ezek az intellektüelek a tudomány, a teológia, a politika különböző terüle- tein, de nagyon is fontossá vált a mindennapi életük, döntéseik, választásaik hátte- re, családi és szellemi gyökereik, egyéni, hitbéli preferenciáik és személyes útkere- sésük. A mikrotörténeti és történeti antropológiai kutatások megindulása a társada- lomnak e rétegét egy időre látszólag háttérbe szorította, és a kis ember figurájába, a kis közösségek formációiba a szellemi elitet -

Observing Protest from a Place

11 VISUAL AND MATERIAL CULTURE, 1300-1700 Goodchild, Oettinger & Prosperetti (eds.) Edited by Karen Hope Goodchild, April Oettinger and Leopoldine Prosperetti Green Worlds in Early Modern Italy Art and the Verdant Earth Green Worlds in Early Modern Italy Modern Early in Worlds Green Green Worlds in Early Modern Italy Visual and Material Culture, 1300–1700 A forum for innovative research on the role of images and objects in the late me- dieval and early modern periods, Visual and Material Culture, 1300–1700 publishes monographs and essay collections that combine rigorous investigation with critical inquiry to present new narratives on a wide range of topics, from traditional arts to seemingly ordinary things. Recognizing the fluidity of images, objects, and ideas, this series fosters cross-cultural as well as multi-disciplinary exploration. We consider proposals from across the spectrum of analytic approaches and methodologies. Series Editor Dr. Allison Levy, an art historian, has written and/or edited three scholarly books, and she has been the recipient of numerous grants and awards, from the Nation- al Endowment for the Humanities, the American Association of University Wom- en, the Getty Research Institute, the Dumbarton Oaks Research Library of Harvard University, the Whiting Foundation and the Bogliasco Foundation, among others. www.allisonlevy.com. Green Worlds in Early Modern Italy Art and the Verdant Earth Edited by Karen Hope Goodchild, April Oettinger and Leopoldine Prosperetti Amsterdam University Press Cover illustration: Giovanni Bellini and Titian, The Feast of the Gods, c.1514–29. Oil on canvas. National Art Gallery, Washington. Cover design: Coördesign, Leiden Lay-out: Newgen/Konvertus isbn 978 94 6298 495 0 e-isbn 978 90 4853 586 6 doi 10.5117/9789462984950 nur 685 © K.H. -

CATALOGUE 339 Juxtapositions Ursus Rare Books

Ursus Rare Books Catalogue 339 Juxtapositions CATALOGUE 339 Juxtapositions T. Peter Kraus URSUS RARE BOOKS, LTD. 50 East 78th Street Suite 1C New York, New York 10075 (212) 772-8787 [email protected] [email protected] Please visit our website at: www.ursusbooks.com Shop Hours: Monday - Friday 10:30 - 6:00 Saturday 11:00 - 5:00 Please inquire for complete descripitons and further images. All prices are net. Postage, packing and insurance are extra. Ursus Rare Books Cover Image: Nos. 23 & 24 Back Cover Image: Nos. 39 & 40 New York City 1. JACOBUS PHILIPPUS DE BERGAMO 2. Henri MATISSE De Claris Mulieribus. Florilège des Amours. Edited by Albertus de Placentia and Augustinus de Casali Maiori. [IV], [I] - CLXX (i.e., 176 folio leaves, By Pierre de Ronsard. 185, [5] pp. Illustrated with 126 lithographs, 125 in sanguine and 1 in black, of misnumbered throughout). Illustrated throughout with woodcuts. Folio, 294 x 195 mm, bound by Fairbairn which 31 are full-page. Folio, 382 x 283 mm, bound by P.-L. Martin in 1966 in full crushed tan morocco, & Armstrong in full green straight-grained morocco. Ferrara: Laurentius de Rubeis, de Valentia, 29 April smooth chocolate brown calf onlays in floral patterns on both covers and spine, abstract but sensuous gilt 1497. filets on top of the design, spine lettered in gilt, with original wrappers bound in. Preserved in matching $ 87,500.00 half-morocco chemise and slipcase. Paris: Albert Skira, 1948. $ 125,000.00 First Edition of one of the foremost illustrated books of the Italian Renaissance. The artist responsible for the illustrations has evaded identification for 500 years, but all the major authorities on early illustrated books concur that Jacobus Philippus de Bergamo’s De Claris Mulieribus is one of the most beautiful A key illustrated book by Henri Matisse which took eight years to produce, bound in an attractive designer illustrated books of the incunabula period. -

Titian, ,A Singular Friend'

CORE Metadata, citation and similar papers at core.ac.uk Originalveröffentlichung in: Kunst und Humanismus. Festschrift für Gosbert Schüßler zum 60. Geburtstag, Provided by ART-Dok herausgegeben von Wolfgang Augustyn und Eckhard Leuschner, Dietmar Klinger Verlag, Passau 2007, S. 261-301 CHARLES DAVIS Titian, ,A singular friend‘ A beautiful, if somewhat mysterious portrait painted by Tiziano Vecellio has found its ,last‘ home in the new world, in far away San Francisco, in a place, that is, which de- rives its name from a Spanish novel describing a paradisiacal island called California (figs. 1, 2, 3). Titian’s authorship of the portrait, now belonging to the San Francisco Art Museums and presently housed at the Palace of the Legion of Honor, is testified to by the painter’s signature, and it has never been questioned since the portrait first re- ceived public notice, belatedly, in 1844, when it appeared in the collection of the Mar- quis of Lansdowne. Less spectacular than some of Titian’s best known portraits, the portrait now in California nonetheless belongs to his finest portrayals of the men of his time. Several identifications have been proposed for the sitter, but none advanced with particular conviction. Although the nameless portrait testifies eloquently to the exi- stence of a noble man at rest, whose existence it indeed preserves and continues, his worldly identity remains an unresolved point of interest.1 The San Francisco Art Museums’ ,Portrait of a Gentleman‘ bear’s Titian’s signa- · ture in the inscription which the sitter holds. It reads unequivocally: D Titiano Vecel- lio / Singolare Amico.