Bach: the Goldberg Variations

Total Page:16

File Type:pdf, Size:1020Kb

Load more

Recommended publications

-

Guest Artist Cello Concert Bryan Hayslett

THE BELHAVEN UNIVERSITY DEPARTMENT OF MUSIC Dr. Stephen W. Sachs, Chair presents Guest Artist Cello Concert Bryan Hayslett Tuesday, October 28, 2014 • 7:30 p.m. Belhaven University Center for the Arts • Concert Hall There will be a reception after the program. Please come and greet the performer. Please refrain from the use of all flash and still photography during the concert. Please turn off all pagers and cell phones. PROGRAM Please hold applause until intermission. Cello Suite No. 6 in D Major, BWV 1012 Johann Sebastian Bach • 1685 - 1750 I. Prelude Unlocked, 1. Make Me a Garment Judith Weir • b. 1954 Unlocked, 2. No Justice A Portrait in Greys Marissa Deitz Wall • b. 1990 Suite No. 6, 2. Allemande J.S. Bach Suite No. 6, 3. Courante Age of the Deceased (Six Months in Chicago) Drew Baker • b. 1978 INTERMISSION Suite No. 6, 4. Sarabande J.S. Bach Suite No. 6, 5. Gavotte A Portrait in Greys Keith Kusterer • b. 1981 Unlocked, 5. Trouble, trouble Judith Weir Suite No. 6, 6. Gigue J.S. Bach A Portrait in Greys by William Carlos Williams Will it never be possible to separate you from your greyness? Must you be always sinking backward into your grey-brown landscapes— And trees always in the distance, always against a grey sky? Must I be always moving counter to you? Is there no place where we can be at peace together and the motion of our drawing apart be altogether taken up? I see myself standing upon your shoulders touching a grey, broken sky— but you, weighted down with me, yet gripping my ankles,—move laboriously on, where it is level and undisturbed by colors. -

The Bach Experience

Marsh Chapel at Boston University THE BACH EXPERIENCE Listeners’ Companion 2018|2019 THE BACH EXPERIENCE Listeners’ Companion 2018|2019 Notes by Brett Kostrzewski Contents Foreword v September 30, 2018 Herr, gehe nicht ins Gerichtmit deinem Knecht BWV105 1 November 18, 2018 Schauet doch und sehet, ob irgendein Schmetz sei BWV46 5 February 10, 2019 Herr Jesu Christ,wahr’ Mensch und Gott BWV 127 9 April 7, 2019 Liebster Gott, wenn werd ich sterben? BWV8 13 Foreword The 2018–2019 Bach Experience at Marsh Chapel marks my fourth year of involvement as annotator, and the second that we have produced this expanded Listeners’ Companion. I remain as grateful, as I was in 2015, for Dr. Scott Allen Jarrett’s invitation to contribute my writing to the Bach Experience, and I am honored to share with you the fruits of my continued study of Johann Sebastian Bach’s remarkable corpus of church cantatas. This year’s Bach Experience divides neatly into two pairs. The first two cantatas were heard on successive Sundays in Leipzig—on 25 July and 1 August 1723, respectively—and you are fortunate to hear them in succession here. The pair, composed only two months after Bach took on his post as Thomaskantor, represent two of his finest accomplishments of the genre, all the more remarkable for appearing on ordinary Sundays in the middle of the summer. I point out some of the compositional elements that link the two cantatas; perhaps you will discover more. The second pair of cantatas were composed during Bach’s second full year in Leipzig, when he took to composing a complete cycle of cantatas primarily based on Lutheran chorales, known as his “chorale cantatas.” I often find the chorale cantatas difficult to write about at length; while their technical aspects are fascinating, particularly Bach’s integration of the chorale melodies, I find their aural experience far more rewarding than anything I could contribute in these notes. -

Bach Unbuttoned

Bach Unbuttoned ANA DE LA VEGA ALEXANDER SITKOVETSKY · RAMÓN ORTEGA QUERO CYRUS ALLYAR · JOHANNES BERGER WÜRTTEMBERGISCHES KAMMERORCHESTER HEILBRONN Johann Sebastian Bach (1685-1750) Suite No. 2 in B Minor (For Flute, Strings & Basso Continuo), BWV 1067 13 VII. Badinerie 1. 24 Brandenburg Concerto No. 5 in D Major (for Flute, Violin & Harpsichord), BWV 1050 Total playing time: 62. 26 1 I. Allegro 9. 22 2 II. Affetuoso 5. 54 3 III. Allegro 5. 11 Brandenburg Concerto No. 4 in G Major (for Violin, Flute & Oboe), BWV 1049 4 I. Allegro 6. 38 5 II. Andante 3. 43 6 III. Presto 4. 28 Brandenburg Concerto No. 2 in F Major (For Trumpet, Flute, Oboe & Violin), BWV 1047 7 I. [Allegro] 4. 35 8 II. Andante 3. 46 9 III. Allegro assai 2. 41 Ana de la Vega, flute Ramón Ortega Quero, oboe Concerto for Two Violins (Flute & Oboe) in D Minor, BWV 1043 Alexander Sitkovetsky, violin 10 I. Vivace 3. 34 Johannes Berger, harpsichord 11 II. Largo ma non tanto 6. 15 Cyrus Allyar, trumpet 12 III. Allegro 4. 38 Württembergisches Kammerorchester Heilbronn The magnificent statue of J.S. Bach outside Yet when you come closer to the statue, one of his solos (likely from a draft version St. Thomas’s Church in Leipzig is, from you see that this man’s buttons are done of Cantata BWV 150). afar, everything we expect: arresting, up incorrectly. austere, and commanding. The godfather Let’s take the case of the Brandenburg of Western classical music tradition, the Standing under the great Carl Seffner Concertos: he wrote several of them master of perfection, precision and balance, statue in Leipzig, I felt I understood for starting c. -

Cantata BWV 40

C. Role. Juin 2012 CANTATE BWV 40 DARZU (Dazu) IST ERSCHIENEN DER SOHN GOTTES C’est pour cela que le Fils de Dieu est apparu… KANTATE ZUM 2. WEINACHTSTAG Cantate pour le deuxième jour de Noël Leipzig, 26 décembre 1723 AVERTISSEMENT Cette notice dédiée à une cantate de Bach tend à rassembler des textes (essentiellement de langue française), des notes et des critiques discographiques souvent peu accessibles (2012). Le but est de donner à lire un ensemble cohérent d’informations et de proposer aux amateurs et mélomanes francophones un panorama espéré parfois élargi de cette partie de l’œuvre vocale de Bach. Outre les quelques interventions « CR » identifiées par des crochets [...] le rédacteur précise qu’il a toujours pris le soin jaloux de signaler sans ambiguïté le nom des auteurs sélectionnés. A cet effet il a indiqué très clairement, entre guillemets «…» toutes les citations fragmentaires tirées de leurs travaux. Rendons à César... ABRÉVIATIONS (A) = la majeur → (a moll) = la mineur (B) = si bémol majeur BB / SPK = Berlin / Staatsbibliothek Preußischer Kulturbesitz B.c. = Basse continue ou continuo BCW = Bach Cantatas Website BD = Bach-Dokumente (4 volumes, 1975) BGA = Bach-Gesellschaft Ausgabe = Société Bach (Leipzig, 1851-1899). J. S. Bach Werke. Gesamtausgabe (édition d’ensemble) der Bachgesellschaft BJ = Bach-Jahrbuch (C) = ut majeur → (c moll) = ut mineur D = Deutschland (D) = Ré majeur → (d moll) = ré mineur (E) = Mi → Es = mi bémol majeur EKG = Evangelisches Kirchen-Gesangbuch. (F) = Fa (G) = Sol majeur. (g moll) = sol mineur GB = Grande Bretagne = Angleterre (H) = Si → (h moll) = si mineur KB. = Kritischer Bericht = Notice critique de la NBA accompagnant chaque cantate NBA = Neue Bach Ausgabe (nouvelle publication de l’œuvre de Bach à partir des années 1954-1955) NBG = Neue Bach Gesellschatf = Nouvelle société Bach (fondée en 1900) OP. -

![Werner-B02c[Erato-10CD].Pdf](https://docslib.b-cdn.net/cover/2163/werner-b02c-erato-10cd-pdf-1912163.webp)

Werner-B02c[Erato-10CD].Pdf

Johann Sebastian Bach (1685-1750) The Cantatas, Volume 2 Heinrich Schütz Choir, Heilbronn Pforzheim Chamber Orchestra Württemberg Chamber Orchestra (B\,\1/ 102, 137, 150) Südwestfunk Orchestra, Baden-Baden (B\,\ry 51, 104) Fritz Werner L'Acad6mie Charles Cros, Grand Prix du disque (BWV 21, 26,130) For complete cantata texts please see www.bach-cantatas.com/IndexTexts.htm cD t 75.22 Ich hatte viel Bekümmernis, BWV 2l My heart and soul were sore distrest . Mon cceur ötait plein d'ffiiction Domenica 3 post Trinitatis/Per ogni tempo Cantata for the Third Sunday after Trinity/For any time Pour le 3n"" Dimanche aprös la Trinitö/Pour tous les temps Am 3. Sonntag nachTrinitatis/Für jede Zeit Prima Parte 0l 1. Sinfonia 3.42 Oboe, violini, viola, basso continuo 02 2. Coro; Ich hatte viel Bekümmernis 4.06 Oboe, violini, viola, fagotto, basso continuo 03 3. Aria (Soprano): Seufzer, Tränen, Kummer, Not 4.50 Oboe, basso continuo ) 04 4. Recitativo (Tenore): Wie hast du dich, mein Gott 1.50 Violini, viola, basso continuo 05 5. Aria (Tenore): Bäche von gesalznen Zähren 5.58 Violini, viola, basso conlinuo 06 6. Coro: Was betrübst du dich, meine Seele 4.35 Oboe, violini, viola, fagotto, basso continuo Seconda Parte 07 7. Recitativo (Soprano, Basso): Ach Iesu, meine Ruh 1.38 Violini, viola, basso continuo 08 8. Duetto (Soprano, Basso): Komm, mein Jesu 4.34 Basso continuo 09 9. Coro: Sei nun wieder zufrieden 6.09 Oboe, tromboni, violini, viola, fagotto, basso continuo l0 10. Aria (Tenore): Erfreue dich, Seele 2.52 Basso continuo 11 11. -

Beyond Bach• Music and Everyday Life in the Eighteenth Century

Beyond Bach• Music and Everyday Life in the Eighteenth Century Andrew Talle Beyond Bach• Beyond Bach• Music and Everyday Life in the Eighteenth Century andrew talle Publication is supported by a grant from the AMS 75 PAYS Endowment of the American Musicological Society, funded in part by the National Endowment for the Humanities and the Andrew W. Mellon Foundation. © 2017 by the Board of Trustees of the University of Illinois All rights reserved Manufactured in the United States of America c 5 4 3 2 1 ∞ This book is printed on acid-free paper. Library of Congress Cataloging-in-Publication Data Names: Talle, Andrew. Title: Beyond Bach : music and everyday life in the eighteenth century / Andrew Talle. Description: Urbana : University of Illinois Press, 2017. | Includes bibliographical references. Identifiers: LCCN 2016041694 (print) | LCCN 2016043348 (ebook) | ISBN 9780252040849 (cloth : alk. paper) | ISBN 9780252099342 (e-book) | ISBN 9780252099342 (E-book) Subjects: LCSH: Music—Social aspects—Germany— History—18th century. | Keyboard players— Germany—Social conditions—18th century. | Germany—Social life and customs—18th century. Classification: LCC ML3917.G3 T35 2017 (print) | LCC ML3917.G3 (ebook) | DDC 786.0943/09032—dc23 LC record available at https://lccn.loc.gov/2016041694 Jacket illustration: Barthold Fritz: Clavichord for Johann Heinrich Heyne (1751). Copyright Victoria and Albert Museum For J. E. Contents Illustrations .................................... ix Acknowledgments .............................. xiii A Note on Currency ............................. xv Introduction ....................................1 1. Civilizing Instruments ............................11 2. The Mechanic and the Tax Collector ...............32 3. A Silver Merchant’s Daughter......................43 4. A Dark-Haired Dame and Her Scottish Admirer ............................66 5. Two Teenage Countesses..........................84 6. -

Tifh CHORALE CANTATAS

BACH'S TREATMIET OF TBE CHORALi IN TIfh CHORALE CANTATAS ThSIS Presented to the Graduate Council of the North Texas State College in Partial Fulfillment of the Requirements For the Degree of MASTER OF ARTS By Floyd Henry quist, B.A. Denton, Texas August, 1950 N. T. S. C. LIBRARY CONTENTS Page LIST OF ILLUSTRATIONS. ...... .... v PIEFACE . vii Chapter I. ITRODUCTION..............1 II. TECHURCH CANTATA.............T S Origin of the Cantata The Cantata in Germany Heinrich Sch-Utz Other Early German Composers Bach and the Chorale Cantata The Cantata in the Worship Service III. TEEHE CHORAI.E . * , . * * . , . , *. * * ,.., 19 Origin and Evolution The Reformation, Confessional and Pietistic Periods of German Hymnody Reformation and its Influence In the Church In Musical Composition IV. TREATENT OF THED J1SIC OF THE CHORAIJS . * 44 Bach's Aesthetics and Philosophy Bach's Musical Language and Pictorialism V. TYPES OF CHORAJETREATENT. 66 Chorale Fantasia Simple Chorale Embellished Chorale Extended Chorale Unison Chorale Aria Chorale Dialogue Chorale iii CONTENTS (Cont. ) Chapter Page VI. TREATMENT OF THE WORDS OF ThE CHORALES . 103 Introduction Treatment of the Texts in the Chorale Cantatas CONCLUSION . .. ................ 142 APPENDICES * . .143 Alphabetical List of the Chorale Cantatas Numerical List of the Chorale Cantatas Bach Cantatas According to the Liturgical Year A Chronological Outline of Chorale Sources The Magnificat Recorded Chorale Cantatas BIBLIOGRAPHY . 161 iv LIST OF ILLUSTRATIO1S Figure Page 1. Illustration of the wave motive from Cantata No. 10e # * * # s * a * # . 0 . 0 . 53 2. Illustration of the angel motive in Cantata No. 122, - - . 55 3. Illustration of the motive of beating wings, from Cantata No. -

BCAS 11803 Mar 2020 Program Rev3 28 Pages.Indd

ANTHONY BLAKE CLARK Music Director SUNDAY, MARCH 1, 2020 Baltimore Choral Arts Society Anthony Blake Clark 54th Season: 2019-20 Sunday, March 1, 2020 at 3 pm Shriver Hall Auditorium, The Johns Hopkins University, Homewood Campus Monteverdi Vespers Anthony Blake Clark, conductor Leo Wanenchak, associate conductor Baltimore Baroque Band, Peabody’s Baroque Orchestra, Dr. John Moran and Risa Browder, co-directors Peabody Renaissance Ensemble, Mark Cudek, director; Adam Pearl, choral coach Washington Cornett and Sackbutt Ensemble, Michael Holmes, director The Baltimore Choral Arts Chorus James Rouvelle and Lili Maya, artists Vespro della Beata Vergine Claudio Monteverdi I. Domine ad adiuvandum II. Dixit dominus III. Nigra sum IV. Laudate pueri V. Pulchra es VI. Laetatus sum VII. Duo seraphim VIII. Nisi dominus Intermission IX. Audi coelum X. Lauda Ierusalem XI. Sonata sopra Sancta Maria ora pro nobis XII. Ave maris stella XIII. Magnificat 2 Monteverdi Vespers is generously sponsored by the William G. Baker, Jr. Memorial Fund, creator of the Baker Artists Portfolios, www.BakerArtists.org. This performance is supported in part by the Maryland State Arts Council (msac.org). Our concerts are also made possible in part by the Citizens of Baltimore County and Mayor Jack Young and the Baltimore Offi ce of Promotion and the Arts. Our media sponsor for this performance is Please turn the pages quietly, and please turn off all electronic devices during the concert. The use of cameras and recording equipment is not allowed. Thanks for your cooperation. Please visit our web site: www.BaltimoreChoralArts.org e-mail: [email protected] 1316 Park Avenue | Baltimore, MD 21217 410-523-7070 Copyright © 2020 by the Baltimore Choral Arts Society Notice: Baltimore Choral Arts Society, Inc. -

March 2019 2 •

2018/19 Season January - March 2019 2 • This spring, two of today's greatest Lieder interpreters, the German baritone Christian Gerhaher and his regular pianist Gerold Huber, return to survey one of the summits of the repertoire, Schubert’s psychologically intense Winterreise. Harry Christophers and The Sixteen join us with a programme of odes, written to welcome Charles II back Director’s to London from his visits to Newmarket, alongside excerpts from Purcell's incidental music to Theodosius, Nathaniel Lee's 1680 tragedy. Introduction Leading Schubert interpreter Christian Zacharias delves into the composer’s unique melodic, harmonic and thematic flourishes in his lecture-recital. Through close examination of these musical hallmarks and idiosyncrasies, he takes us on a journey to the very essence of Schubert’s style. With her virtuosic ability to sing anything from new works to Baroque opera and Romantic Lieder with exceptional quality, Marlis Petersen is one of the most enterprising singers today. Her residency continues with two concerts, sharing the stage with fellow singers and accompanists of international acclaim. This year’s Wigmore Hall Learning festival, Sense of Home, celebrates the diversity and multicultural melting pot that is London and the borough of Westminster, reflects on Wigmore Hall as a place many call home, and invites you to explore what ‘home’ means to you. One of the most admired singers of the present day, Elīna Garanča, will open the 2018/19 season at the Metropolitan Opera as Dalila in Saint-Saëns’ Samson et Dalila. Her programme in February – comprising four major cycles – includes Wagner's Wesendonck Lieder, two of which were identified by the composer himself as studies for Tristan und Isolde. -

Bach: the Master and His Milieu June 23-30, 2019

39th Annual Season Bach: The Master and His Milieu June 23-30, 2019 39th Annual Festival Bach: The Master and His Milieu Elizabeth Blumenstock, Artistic Director elcome to the 2019 edition of the Baroque Music Festival, Corona del WMar! Once again, we continue the tradition established by our founder, Burton Karson, of presenting five concerts over eight days. Violinist Elizabeth Blumenstock, now in her ninth year as artistic director, programmed her first “Bach-Fest” back in 2015, and this year she felt the time was right to revisit the concept: a week of glorious Bach, explored from many angles. Our Festival Finale has always been devoted to vocal masterpieces; this year the Wednesday program is too. And the “Milieu” of this season’s title will be explored through music by Bach’s influencers and contemporaries, creating a fascinating historical and musical journey. Thank you for being an integral part of this year’s Festival. We are grateful to you — our donors, foundation contributors, corporate partners, advertisers and concertgoers — for your ongoing and generous support. Festival Board of Directors Patricia Bril, President The Concerts Sunday, June 23 ..................Back to Bach Concertos ..........................8 Monday, June 24 ................Glories of the Guitar .............................14 Wednesday, June 26 ..........Passionate Voices ...................................18 Friday, June 28 ...................Bach’s Sons, Friends and Rivals ...........28 Sunday, June 30 ..................Bach the Magnificent ............................36 All concerts are preceded by brass music performed al fresco (see page 55) and followed by a complimentary wine & waters reception to which you are cordially invited to mingle with the performers. 3 M. & R. Weisshaar & Son Violin Shop, Inc. -

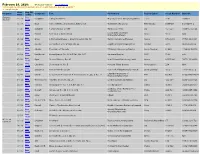

Sunday Playlist

February 16, 2020: (Full-page version) Close Window “There was no one near to confuse me, so I was forced to become original.” — Joseph Haydn Start Buy CD Program Composer Title Performers Record Label Stock Number Barcode Time online Sleepers, Buy 00:01 Corigliano Lullaby for Natalie Meyers/London Symphony/Slatkin e one 7791 099923 Awake! Now! Buy 00:07 Bach Cello Suite No. 2 in D minor, BWV 1008 Mstislav Rostropovich EMI Classics 55364/5 D 273269-1 Now! Buy 00:30 Schubert 4 Impromptus, D. 899 Maria Joao Pires DG 457 550 028945755021 Now! Buy Los Angeles Chamber 01:01 Handel Suite in G ~ Water Music Delos 3010 N/A Now! Orchestra/Schwarz Buy 01:12 Grieg 3 Orchestral Pieces ~ Sigurd Jorsalfar, Op. 56 Malmö Symphony/Engeset Naxos 8.508015 747313801534 Now! Buy 01:30 Dvorak Serenade in E for Strings, Op.22 English String Orch/Boughton Nimbus 5016 08360350162 Now! Buy 02:00 Sibelius The Swan of Tuonela Pittsburgh Symphony/Maazel Sony Classical 61963 074646196328 Now! Buy 02:13 Beethoven String Quartet No. 12 in E flat, Op. 127 Smetana Quartet PCM 7063 n/a Now! Buy 02:50 Elgar Dream Children, Op. 43 New Zealand Symphony/Judd Naxos 8.557166 747313216628 Now! Buy 03:00 Chadwick String Quartet No. 5 Portland String Quartet Northeastern 234 N/A Now! Buy 03:34 Strauss Jr. Roses from the South New York Philharmonic/Bernstein Sony Classical 46710 07464467102 Now! Buy Chamber Orchestra of 03:47 Vivaldi Concerto in B minor for 4 Violins and Cello, Op. 3 No. 10 EMI 69143 5099976914324 Now! Toulouse/Auriacombe Buy 04:01 Mendelssohn Hebrides Overture, Op. -

Download Issue

AMERICAN CHORAL REVIEW PAUL HENRY LANG BACH AND HANDEL JOURNAL OF THE AMERICAN CHORAL FOUNDATION, INC. VOLUME XVII · NUMBER 4 · OCTOBER, 1975 AMERICAN CHORAL REVIEW ALFRED 11ANN, Editor ALFREDA HAYS, Auistant Editor Associate Editors EDWARD TATNALL CANBY ANDREW c. MINOR RICHARD JACKSON MARTIN PICKER JACK RAMEY THE AMERICAN CHORAL REVIEW is published quarterly as the official journal of the Association of Choral Conductors sponsored by The American Choral Founda tion, Inc. The Fouodation also publishes a supplementary Research Memorandum Series and maintains a reference library of current publications of choral works. Membership in the Association of Choral Conductors is available for an annual contribution of $20.00 and includes subscriptions to the AMERICAN CHORAL REVIEW and the Research Memorandum Series and use of the Foundation's Advisory Services Division and reference library. All contributions are tax deductible. Back issues of the AMERICAN CHORAL REVIEW are available to members at $2.25; back issues of the Research Memorandum Series at $1.50. Bulk prices will be quoted on request. THE AMERICAN CHORAL FoUNDATioN, INc. SHELDON SoFFER, Administrative Director 130 West 56th Street New York, New York 10019 Editorial Address 215 Kent Place Boulevard Summit, New Jersey 07901 Material submitted for publication should be sent in duplicate to the editorial address. All typescripts should be double-spaced and have ample margins. Footnotes should be placed at the bottom of the pages to which they refer. Music examples should preferably appear