"If You Want Sense, You'll Have to Make It Yourself": Language, Adaptation, and the Myth of Visual Nonsense" (2016)

Total Page:16

File Type:pdf, Size:1020Kb

Load more

Recommended publications

-

Open Maryallenfinal Thesis.Pdf

THE PENNSYLVANIA STATE UNIVERSITY SCHREYER HONORS COLLEGE DEPARTMENT OF ENGLISH SIX IMPOSSIBLE THINGS BEFORE BREAKFAST: THE LIFE AND MIND OF LEWIS CARROLL IN THE AGE OF ALICE’S ADVENTURES IN WONDERLAND MARY ALLEN SPRING 2020 A thesis submitted in partial fulfillment of the requirements for a baccalaureate degree in English with honors in English Reviewed and approved* by the following: Kate Rosenberg Assistant Teaching Professor of English Thesis Supervisor Christopher Reed Distinguished Professor of English, Visual Culture, and Women’s, Gender, and Sexuality Studies Honors Adviser * Electronic approvals are on file. i ABSTRACT This thesis analyzes and offers connections between esteemed children’s literature author Lewis Carroll and the quality of mental state in which he was perceived by the public. Due to the imaginative nature of Alice’s Adventures in Wonderland, it has been commonplace among scholars, students, readers, and most individuals familiar with the novel to wonder about the motive behind the unique perspective, or if the motive was ever intentional. This thesis explores the intentionality, or lack thereof, of the motives behind the novel along with elements of a close reading of Alice’s Adventures in Wonderland. It additionally explores the origins of the concept of childhood along with the qualifications in relation to time period, culture, location, and age. It identifies common stereotypes and presumptions within the subject of mental illness. It aims to achieve a connection between the contents of Carroll’s novel with -

Summer Classic Film Series, Now in Its 43Rd Year

Austin has changed a lot over the past decade, but one tradition you can always count on is the Paramount Summer Classic Film Series, now in its 43rd year. We are presenting more than 110 films this summer, so look forward to more well-preserved film prints and dazzling digital restorations, romance and laughs and thrills and more. Escape the unbearable heat (another Austin tradition that isn’t going anywhere) and join us for a three-month-long celebration of the movies! Films screening at SUMMER CLASSIC FILM SERIES the Paramount will be marked with a , while films screening at Stateside will be marked with an . Presented by: A Weekend to Remember – Thurs, May 24 – Sun, May 27 We’re DEFINITELY Not in Kansas Anymore – Sun, June 3 We get the summer started with a weekend of characters and performers you’ll never forget These characters are stepping very far outside their comfort zones OPENING NIGHT FILM! Peter Sellers turns in not one but three incomparably Back to the Future 50TH ANNIVERSARY! hilarious performances, and director Stanley Kubrick Casablanca delivers pitch-dark comedy in this riotous satire of (1985, 116min/color, 35mm) Michael J. Fox, Planet of the Apes (1942, 102min/b&w, 35mm) Humphrey Bogart, Cold War paranoia that suggests we shouldn’t be as Christopher Lloyd, Lea Thompson, and Crispin (1968, 112min/color, 35mm) Charlton Heston, Ingrid Bergman, Paul Henreid, Claude Rains, Conrad worried about the bomb as we are about the inept Glover . Directed by Robert Zemeckis . Time travel- Roddy McDowell, and Kim Hunter. Directed by Veidt, Sydney Greenstreet, and Peter Lorre. -

Tom Hanks Halle Berry Martin Sheen Brad Pitt Robert Deniro Jodie Foster Will Smith Jay Leno Jared Leto Eli Roth Tom Cruise Steven Spielberg

TOM HANKS HALLE BERRY MARTIN SHEEN BRAD PITT ROBERT DENIRO JODIE FOSTER WILL SMITH JAY LENO JARED LETO ELI ROTH TOM CRUISE STEVEN SPIELBERG MICHAEL CAINE JENNIFER ANISTON MORGAN FREEMAN SAMUEL L. JACKSON KATE BECKINSALE JAMES FRANCO LARRY KING LEONARDO DICAPRIO JOHN HURT FLEA DEMI MOORE OLIVER STONE CARY GRANT JUDE LAW SANDRA BULLOCK KEANU REEVES OPRAH WINFREY MATTHEW MCCONAUGHEY CARRIE FISHER ADAM WEST MELISSA LEO JOHN WAYNE ROSE BYRNE BETTY WHITE WOODY ALLEN HARRISON FORD KIEFER SUTHERLAND MARION COTILLARD KIRSTEN DUNST STEVE BUSCEMI ELIJAH WOOD RESSE WITHERSPOON MICKEY ROURKE AUDREY HEPBURN STEVE CARELL AL PACINO JIM CARREY SHARON STONE MEL GIBSON 2017-18 CATALOG SAM NEILL CHRIS HEMSWORTH MICHAEL SHANNON KIRK DOUGLAS ICE-T RENEE ZELLWEGER ARNOLD SCHWARZENEGGER TOM HANKS HALLE BERRY MARTIN SHEEN BRAD PITT ROBERT DENIRO JODIE FOSTER WILL SMITH JAY LENO JARED LETO ELI ROTH TOM CRUISE STEVEN SPIELBERG CONTENTS 2 INDEPENDENT | FOREIGN | ARTHOUSE 23 HORROR | SLASHER | THRILLER 38 FACTUAL | HISTORICAL 44 NATURE | SUPERNATURAL MICHAEL CAINE JENNIFER ANISTON MORGAN FREEMAN 45 WESTERNS SAMUEL L. JACKSON KATE BECKINSALE JAMES FRANCO 48 20TH CENTURY TELEVISION LARRY KING LEONARDO DICAPRIO JOHN HURT FLEA 54 SCI-FI | FANTASY | SPACE DEMI MOORE OLIVER STONE CARY GRANT JUDE LAW 57 POLITICS | ESPIONAGE | WAR SANDRA BULLOCK KEANU REEVES OPRAH WINFREY MATTHEW MCCONAUGHEY CARRIE FISHER ADAM WEST 60 ART | CULTURE | CELEBRITY MELISSA LEO JOHN WAYNE ROSE BYRNE BETTY WHITE 64 ANIMATION | FAMILY WOODY ALLEN HARRISON FORD KIEFER SUTHERLAND 78 CRIME | DETECTIVE -

Examining the Relationship Between Children's

A Spoonful of Silly: Examining the Relationship Between Children’s Nonsense Verse and Critical Literacy by Bonnie Tulloch B.A., (Hons), Simon Fraser University, 2013 A THESIS SUBMITTED IN PARTIAL FULFILLMENT OF THE REQUIREMENTS FOR THE DEGREE OF MASTER OF ARTS in THE FACULTY OF GRADUATE AND POSTDOCTORAL STUDIES (Children’s Literature) THE UNIVERSITY OF BRITISH COLUMBIA (Vancouver) December 2015 © Bonnie Tulloch, 2015 Abstract This thesis interrogates the common assumption that nonsense literature makes “no sense.” Building off research in the fields of English and Education that suggests the intellectual value of literary nonsense, this study explores the nonsense verse of several North American children’s poets to determine if and how their play with language disrupts the colonizing agenda of children’s literature. Adopting the critical lenses of Translation Theory and Postcolonial Theory in its discussion of Dr. Seuss’s On Beyond Zebra! (1955) and I Can Read with My Eyes Shut! (1978), along with selected poems from Shel Silverstein’s Where the Sidewalk Ends (1974), A Light in the Attic (1981), Runny Babbit (2005), Dennis Lee’s Alligator Pie (1974), Nicholas Knock and Other People (1974), and JonArno Lawson’s Black Stars in a White Night Sky (2006) and Down in the Bottom of the Bottom of the Box (2012), this thesis examines how the foreignizing effect of nonsense verse exposes the hidden adult presence within children’s literature, reminding children that childhood is essentially an adult concept—a subjective interpretation (i.e., translation) of their lived experiences. Analyzing the way these poets’ nonsense verse deviates from cultural norms and exposes the hidden adult presence within children’s literature, this research considers the way their poetry assumes a knowledgeable implied reader, one who is capable of critically engaging with the text. -

1.Hum-Roald Dahl's Nonsense Poetry-Snigdha Nagar

IMPACT: International Journal of Research in Humanities, Arts and Literature (IMPACT: IJRHAL) ISSN(P): 2347-4564; ISSN(E): 2321-8878 Vol. 4, Issue 4, Apr 2016, 1-8 © Impact Journals ROALD DAHL’ S NONSENSE POETRY: A METHOD IN MADNESS SNIGDHA NAGAR Research Scholar, EFL University, Tarnaka, Hyderabad, India ABSTRACT Following on the footsteps of writers like Louis Carroll, Edward Lear, and Dr. Seuss, Roald Dahl’s nonsensical verses create a realm of semiotic confusion which negates formal diction and meaning. This temporary reshuffling of reality actually affirms that which it negates. In other words, as long as it is transitory the ‘nonsense’ serves to establish more firmly the authority of the ‘sense.’ My paper attempts to locate Roald Dahl’s verse in the field of literary nonsense in as much as it avows that which it appears to parody. Set at the brink of modernism these poems are a playful inditement of Victorian conventionality. The three collections of verses Rhyme Stew, Dirty Beasts, and Revolving Rhyme subvert social paradigms through their treatment of censorship and female sexuality. Meant primarily for children, these verses raise a series of uncomfortable questions by alienating the readers with what was once familiar territory. KEYWORDS : Roald Dahl’s Poetry, Subversion, Alienation, Meaning, Nonsense INTRODUCTION The epistemological uncertainty that manifested itself during the Victorian mechanization reached its zenith after the two world wars. “Even signs must burn.” says Jean Baudrillard in For a Critique of the Political Economy of the Sign (1981).The metaphor of chaos was literalized in works of fantasy and humor in all genres. -

Humour in Nonsense Literature

http://dx.doi.org/10.7592/EJHR2017.5.3.holobut European Journal of Humour Research 5 (3) 1–3 www.europeanjournalofhumour.org Editorial: Humour in nonsense literature Agata Hołobut Jagiellonian University, Kraków, Poland [email protected] Władysław Chłopicki Jagiellonian University, Kraków, Poland [email protected] The present special issue is quite unique. It grew out of a one-off scholarly seminar entitled BLÖÖF: Nonsense in Translation and Beyond, which attracted international scholars to the Institute of English Studies of Kraków’s Jagiellonian University on 18 May 2016 – a venue which had earlier yielded the series of studies entitled In Search of (Non)Sense (Chrzanowska- Kluczewska & Szpila 2009). The discussion at the seminar brought everyone to the, perhaps inevitable, conclusion that nonsense is bound to be humorous, and thus nonsense is definitely within the scope of humour studies. “Nonsense expressions easily become humorous ones, as humans often obtain pleasure from linguistic play and are ready to look for alternative paths to produce meaning. Nonsense has been experienced as a form of freedom, especially as a means to free thinking from the conventional bindings of logic and language” (Viana 2014). The interest in literary nonsense is quite long dating back to such grand figures as Dante, Rabelais, Erasmus of Rotterdam, and especially notably to the Anglosphere with its grand figures of Jonathan Swift, Lawrence Sterne, Edward Lear, Lewis Carroll, James Joyce, and Samuel Beckett. At least since the time of Lewis Carroll and the antics of Alice in Wonderland nonsense humour rose to the status of a ‘typically English’ phenomenon, and the subject of creative nonsense or sense in nonsense has been quite prominent in English-language literary studies, whether of verse or prose. -

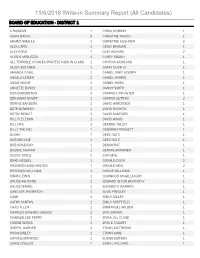

11/6/2018 Write-In Summary Report (All Candidates) BOARD of EDUCATION - DISTRICT 1

11/6/2018 Write-in Summary Report (All Candidates) BOARD OF EDUCATION - DISTRICT 1 A RAINEAR 1 CHRIS MURRAY 1 ADAM HATCH 2 CHRISTINE ASHOO 1 AHMED SMALLS 1 CHRISTINE KUSHNER 2 ALEX CARR 1 CINDY BEAMAN 1 ALEX FORD 1 CLAY WILKINS 2 ALICE E VERLEZZA 1 COREY BRUSH 1 ALL TERRIBLE CHOICES PROTECT KIDS IN CLASS 1 CYNTHIA WOOLARD 1 ALLEN BUTCHER 1 DAFFY DUCK III 1 AMANDA GOWL 1 DANIEL GREY SCURRY 1 ANGELA LEISER 2 DANIEL HARRIS 1 ANGIE WIGHT 1 DANIEL HORN 1 ANNETTE BUSBY 1 DANNY SMITH 1 BEN DOBERSTEIN 2 DAPHNE LANCASTER 1 BENJAMIN DOVER 1 DAPHNE SUTTON 2 BERNIE SANDERS 1 DAVID HARDISTER 1 BETH BOWMAN 1 DAVID RUNYON 1 BETSY BENOIT 1 DAVID SANFORD 1 BILL FLELEHAN 1 DAVID WOOD 1 BILL NYE 1 DEANNE TALLEY 1 BILLY THE KID 1 DEBORAH PRICKETT 1 BLANK 7 DEEZ NUTS 1 BOB MELONE 1 DEEZ NUTZ 1 BOB SPAZIANO 1 DEMOCRAT 1 BOBBIE CAVNAR 1 DENNIS BRAWNER 1 BOBBY JONES 1 DON MIAL 1 BRAD HESSEL 1 DONALD DUCK 2 BRANDON WASHINGTON 1 DONALD MIAL 2 BRANNON WILLIAMS 1 DONNE WILLIAMS 1 BRIAN LEWIS 1 DURWOOD MCGILLACUDY 1 BRUCE ASHFORD 1 EDWARD ALTON HUNTER IV 1 BRUCE MAMEL 1 ELIZABETH WARREN 1 CANDLER THORNTON 1 ELVIS PRESLEY 1 CASH 1 EMILY JOLLEY 1 CATHY SANTOS 1 EMILY SHEFFIELD 1 CHAD ALLEN 1 EMMANUEL WILDER 1 CHARLES EDWARD CHEESE 1 ERIC BROWN 1 CHARLES LEE PERRY 1 ERIKA JILL CLOSE 1 CHERIE WIGGS 1 ERIN E O'LEARY 1 CHERYL GARNER 1 ETHAN MATTHEWS 1 CHRIS BAILEY 1 ETHAN SIMS 1 CHRIS BJORNSTED 1 EUSHA BURTON 1 CHRIS COLLUM 1 EVAN L POLLARD 1 11/6/2018 Write-in Summary Report (All Candidates) BOARD OF EDUCATION - DISTRICT 1 EVERITT 1 JIMMY ALSTON 1 FELIX KEYES 1 JO ANNE -

ED WYNN "The Fire Chief" Publication of the Old Time Radio Club

Established 1975 Number 279 April 2000 ED WYNN "The Fire Chief" Publication of the Old Time Radio Club Membership Information Club Officers and Librarians New member processing, $5 plus club member President ship of $17.50 per year from January 1 to Jerry Collins (716) 683-6199 December 31. Members receive a tape library list 56 Christen Ct. ing, reference library listing and a monthly newslet Lancaster, NY 14086 ter. Memberships are as follows: if you join January-March, $17.50; April-June, $14; July Vice President & Canadian Branch September, $10; October-December, $7. All Richard Simpson renewals should be sent in as soon as possible to 960 16 Road R.R. 3 avoid missing issues. Please be sure to notify us if Fenwick, Ontario you have a change of address. The Old Time Canada, LOS 1CO Radio Club meets the first Monday of every month at 7:30 PM during the months of September to Treasurer, Back Issues, Videos & Records June at 393 George Urban Blvd., Cheektowaga, NY Dominic Parisi (716) 884-2004 14225. The club meets informally during the 38 Ardmore PI. months of July and August at the same address. Buffalo, NY 14213 Anyone interested in the Golden Age of Radio is welcome. The Old Time Radio Club is affiliated Membership Renewals, Change of Address, with The Old Time Radio Network. Cassette Library - #2000 and YR. Illustrated Press Cover Designs Club Mailing Address .Peter Bellanca (716) 773-2485 Old Time Radio Club 1620 Ferry Road 56 Christen Ct. Grand Island, NY 14072 Lancaster, NY 14086 Membership Inquires and OTR Network Related Items Back issues of The IllustratedPress are $1.50 post Richard Olday (716) 684-1604 paid. -

Finding Sense Behind Nonsense in Select Poems of Sukumar Ray

Journal of the Department of English Vidyasagar University Vol. 12, 2014-2015 Finding Sense Behind Nonsense in Select Poems of Sukumar Ray Rima Chakraborty Nonsense literature is generally categorized as part of the macrocosm of children’s literature. And there is no denying that as children we have all read such literary pieces with much amusement and delight. In 1900 G.K. Chesterton wrote that, if he were to be asked for the best proof of ‘adventurous growth’ in the nineteenth century, he would reply, “with all respect for its portentous science and philosophy, that it was to be found in the literature of nonsense” and that “this was the literature of the future” (Chesterton 43). Now, “Nonsense” as a literary genre is difficult to define in absolute terms. It is interpretation gone wild, but also lucid, as clearly appears in the works of the early practitioners of the form in the mid 19th century, namely Edward Lear and Lewis Carroll. It is true that the “modern nonsense” originated in the mid- 19th century, but it is equally true that the roots of the tradition can be traced back to some of its early practitioners and precursors- such as the anonymous nonsense of nursery rhymes, the ‘water poet’ John Taylor and the Bedlamite and mad talk of Shakespeare. Again, if the genre of literary nonsense is analyzed with reference to its contemporary socio-political scenario, it becomes clear that nonsense is actually a medium which allows the literary artist to point out various shortcomings of the society at large. So, as its name suggests, “non-sense” always exists in relation to, and as a comment on, “sense.” T. -

Red' Skelton and Clem Kadiddlehopper

Red’Skelton and Clem Kadiddlehopper Wes D.Gehring* “Things have sunk lower than a snake’s belly” [a popular comment by Red Skelton’s Clem Kadiddlehopperl. Newspaper journalist John Crosby in 1952: “How [comically] stupid can you get?” Skelton: “I don’t know. I’m still pretty young.”’ From the books of George Ade, Kin Hubbard, and Will Cuppy to the television work of Herb Shriner and David Letterman, Indi- ana’s humor has long entertained the nation. But Red Skelton’s more-than-fifty-year reign as a Hoosier comedy artist of national significance and his ongoing ties to the state-particularly as his character Clem Kadiddlehopper-place him in a peerless position among Indiana comedians. Since the 1930s Red, fittingly, has achieved success in every medium that he has attempted, including vaudeville, radio, television, and motion pictures. The cornerstone of the comedian’s career is the unprecedented twenty-year televi- sion run (1951-1971) of his variety show. All artists’ backgrounds provide special insights into their work, but there seems to be a unique fascination with the biogra- phies of humorists. Clowns comically comfort audiences with their physical and spiritual resilience. In addition, society seems espe- cially spellbound with the clown chronicle that reveals tragic roots-the ability to provoke laughter despite personal sadness. Once again Skelton is in a unique category among Indiana humorists, for he survived the harshest of childhoods. His circus clown father died an alcohol-related death before Red was born, and as a youth he endured tattered clothing, taunts about his “Wes D. -

Chapter Template

Copyright by Colleen Leigh Montgomery 2017 THE DISSERTATION COMMITTEE FOR COLLEEN LEIGH MONTGOMERY CERTIFIES THAT THIS IS THE APPROVED VERSION OF THE FOLLOWING DISSERTATION: ANIMATING THE VOICE: AN INDUSTRIAL ANALYSIS OF VOCAL PERFORMANCE IN DISNEY AND PIXAR FEATURE ANIMATION Committee: Thomas Schatz, Supervisor James Buhler, Co-Supervisor Caroline Frick Daniel Goldmark Jeff Smith Janet Staiger ANIMATING THE VOICE: AN INDUSTRIAL ANALYSIS OF VOCAL PERFORMANCE IN DISNEY AND PIXAR FEATURE ANIMATION by COLLEEN LEIGH MONTGOMERY DISSERTATION Presented to the Faculty of the Graduate School of The University of Texas at Austin in Partial Fulfillment of the Requirements for the Degree of DOCTOR OF PHILOSOPHY THE UNIVERSITY OF TEXAS AT AUSTIN AUGUST 2017 Dedication To Dash and Magnus, who animate my life with so much joy. Acknowledgements This project would not have been possible without the invaluable support, patience, and guidance of my co-supervisors, Thomas Schatz and James Buhler, and my committee members, Caroline Frick, Daniel Goldmark, Jeff Smith, and Janet Staiger, who went above and beyond to see this project through to completion. I am humbled to have to had the opportunity to work with such an incredible group of academics whom I respect and admire. Thank you for so generously lending your time and expertise to this project—your whose scholarship, mentorship, and insights have immeasurably benefitted my work. I am also greatly indebted to Lisa Coulthard, who not only introduced me to the field of film sound studies and inspired me to pursue my intellectual interests but has also been an unwavering champion of my research for the past decade. -

Dr. Strangelove's America

Dr. Strangelove’s America Literature and the Visual Arts in the Atomic Age Lecturer: Priv.-Doz. Dr. Stefan L. Brandt, Guest Professor Room: AR-H 204 Office Hours: Wednesdays 4-6 pm Term: Summer 2011 Course Type: Lecture Series (Vorlesung) Selected Bibliography Non-Fiction A Abrams, Murray H. A Glossary of Literary Terms. Seventh Edition. Fort Worth, Philadelphia, et al: Harcourt Brace College Publ., 1999. Abrams, Nathan, and Julie Hughes, eds. Containing America: Cultural Production and Consumption in the Fifties America. Birmingham, UK: University of Birmingham Press, 2000. Adler, Kathleen, and Marcia Pointon, eds. The Body Imaged. Cambridge: Cambridge Univ. Press, 1993. Alexander, Charles C. Holding the Line: The Eisenhower Era, 1952-1961. Bloomington, Indiana: Indiana Univ. Press, 1975. Allen, Donald M., ed. The New American Poetry, 1945-1960. New York: Grove Press, 1960. ——, and Warren Tallman, eds. Poetics of the New American Poetry. New York: Grove Press, 1973. Allen, Richard. Projecting Illusion: Film Spectatorship and the Impression of Reality. Cambridge: Cambridge Univ. Press, 1997. Allsop, Kenneth. The Angry Decade: A Survey of the Cultural Revolt of the Nineteen-Fifties. [1958]. London: Peter Owen Limited, 1964. Ambrose, Stephen E. Eisenhower: The President. New York: Simon and Schuster, 1984. “Anatomic Bomb: Starlet Linda Christians brings the new atomic age to Hollywood.” Life 3 Sept. 1945: 53. Anderson, Christopher. Hollywood TV: The Studio System in the Fifties. Austin: Univ. of Texas Press, 1994. Anderson, Jack, and Ronald May. McCarthy: the Man, the Senator, the ‘Ism’. Boston: Beacon Press, 1952. Anderson, Lindsay. “The Last Sequence of On the Waterfront.” Sight and Sound Jan.-Mar.