Red' Skelton and Clem Kadiddlehopper

Total Page:16

File Type:pdf, Size:1020Kb

Load more

Recommended publications

-

George Ade Papers

A GUIDE TO THE GEORGE ADE PAPERS PURDUE UNIVERSITY LIBRARIES ARCHIVES AND SPECIAL COLLECTIONS © Purdue University, West Lafayette, Indiana Last Revised: July 26, 2007 Compiled By: Joanne Mendes, Archives Assistant TABLE OF CONTENTS Page(s) 1. Descriptive Summary……………………………………………….4 2. Restrictions on Access………………………………………………4 3. Related Materials……………………………………………………4-5 4. Subject Headings…………………………………………………….6 5. Biographical Sketch.......................………………………………….7-10 6. Scope and Content Note……….……………………………………11-13 7. Inventory of the Papers…………………………………………….14-100 Correspondence……...………….14-41 Newsletters……………………….....42 Collected Materials………42-43, 73, 99 Manuscripts……………………...43-67 Purdue University……………….67-68 Clippings………………………...68-71 Indiana Society of Chicago……...71-72 Scrapbooks and Diaries………….72-73 2 Artifacts…………………………..74 Photographic Materials………….74-100 Oversized Materials…………70, 71, 73 8. George Ade Addendum Collection ………………………………101-108 9. George Ade Filmography...............................................................109-112 3 Descriptive Summary Creator: Ade, George, 1866-1944 Title: The George Ade Papers Dates: 1878-1947 [bulk 1890s-1943] Abstract: Creative writings, correspondence, photographs, printed material, scrapbooks, and ephemera relating to the life and career of author and playwright George Ade Quantity: 30 cubic ft. Repository: Archives and Special Collections, Purdue University Libraries Acquisition: Gifts from George Ade, James Rathbun (George Ade's nephew by marriage and business manager), -

Spring 2014 Commencement Program

TE TA UN S E ST TH AT I F E V A O O E L F A DITAT DEUS N A E R R S I O Z T S O A N Z E I A R I T G R Y A 1912 1885 ARIZONA STATE UNIVERSITY COMMENCEMENT AND CONVOCATION PROGRAM Spring 2014 May 12 - 16, 2014 THE NATIONAL ANTHEM THE STAR SPANGLED BANNER O say can you see, by the dawn’s early light, What so proudly we hailed at the twilight’s last gleaming? Whose broad stripes and bright stars through the perilous fight O’er the ramparts we watched, were so gallantly streaming? And the rockets’ red glare, the bombs bursting in air Gave proof through the night that our flag was still there. O say does that Star-Spangled Banner yet wave O’er the land of the free and the home of the brave? ALMA MATER ARIZONA STATE UNIVERSITY Where the bold saguaros Raise their arms on high, Praying strength for brave tomorrows From the western sky; Where eternal mountains Kneel at sunset’s gate, Here we hail thee, Alma Mater, Arizona State. —Hopkins-Dresskell MAROON AND GOLD Fight, Devils down the field Fight with your might and don’t ever yield Long may our colors outshine all others Echo from the buttes, Give em’ hell Devils! Cheer, cheer for A-S-U! Fight for the old Maroon For it’s Hail! Hail! The gang’s all here And it’s onward to victory! Students whose names appear in this program have completed degree requirements. -

Summer Classic Film Series, Now in Its 43Rd Year

Austin has changed a lot over the past decade, but one tradition you can always count on is the Paramount Summer Classic Film Series, now in its 43rd year. We are presenting more than 110 films this summer, so look forward to more well-preserved film prints and dazzling digital restorations, romance and laughs and thrills and more. Escape the unbearable heat (another Austin tradition that isn’t going anywhere) and join us for a three-month-long celebration of the movies! Films screening at SUMMER CLASSIC FILM SERIES the Paramount will be marked with a , while films screening at Stateside will be marked with an . Presented by: A Weekend to Remember – Thurs, May 24 – Sun, May 27 We’re DEFINITELY Not in Kansas Anymore – Sun, June 3 We get the summer started with a weekend of characters and performers you’ll never forget These characters are stepping very far outside their comfort zones OPENING NIGHT FILM! Peter Sellers turns in not one but three incomparably Back to the Future 50TH ANNIVERSARY! hilarious performances, and director Stanley Kubrick Casablanca delivers pitch-dark comedy in this riotous satire of (1985, 116min/color, 35mm) Michael J. Fox, Planet of the Apes (1942, 102min/b&w, 35mm) Humphrey Bogart, Cold War paranoia that suggests we shouldn’t be as Christopher Lloyd, Lea Thompson, and Crispin (1968, 112min/color, 35mm) Charlton Heston, Ingrid Bergman, Paul Henreid, Claude Rains, Conrad worried about the bomb as we are about the inept Glover . Directed by Robert Zemeckis . Time travel- Roddy McDowell, and Kim Hunter. Directed by Veidt, Sydney Greenstreet, and Peter Lorre. -

R1 · R ·Rl Lr

� --1·1 r� · --·t· r-1 � -r� --·rl �l_, r�·r p· ,("' __, .:..../ --rl 0 F 521 148 VOL 16 N01 - - - - INDIANA HISTORICAL SOCIETY BOARD OF TRUSTEES SARAH Evru'\'S BARKER, indianapolis MICH.\ELA. SIKK.\IAN, Indianapolis, Second Vice Chair �� \RY A.J-..:-...: BRADLEY, Indianapolis £0\\.\.RI) E. BREEN, �[arion, First Vice Chair 01.\.\!,E j. C\RT�tEL, Brownstown P•TRICL\ D. CeRRA!<, Indianapolis EOCAR G1 EXN 0.-\\15, Indianapolis DA.." l:. I �1. E�'T. Indianapolis RIC! lARD F'ELDMA-'-.;,Indianapolis RICHARD E. FoRD, Wabash R. RAY HAWKINS. Carmel TI!O\!A-<.; G. HOR\CK, Indianapolis MARTIN L<\KE, 1'1arion L\RRY S. L\NDIS, Indianapolis P01.1 'Jo�TI LEi'\NON,Indianapolis jAMES H. MADISON, Bloomington M \RY jA...'\'E �IEEJ.�ER. Carmel AMlRF\\ '"'· NiCKLE, South Bend GJ::.ORGJ::. F. RAPP,Indianapolis BO'<'IIE A. REILLY, Indianapolis E\'AIIt'\FII. RIIOOI:.II.AME.L,Indianapolis, Secretary LA:-.J M. Rou.�\!'-10, Fon \-\'ayne, Chair jMIES SHOOK JR., Indianapolis P. R. SwEENEY, Vincennes, Treasurer R BERT B. TOOTHAKER, South Bend WILLIAM H. WIGGINS JR., Bloomington ADMINISTRATION SALVATORE G. CILELLAjR., President RA�IOND L. SIIOI:.MAKER, Executive Vice President ANMBELLF J.JACKSON, Comroller St!SAN P. BROWN, enior Director, Human Resources STEPIIl:-.. L. Cox, Vice President, Collections, Conserv-ation, and Public Programs TIIO\IAS A. �lAsoN, Vice President, n-JS Press Ll:'\DA L. PRArr, Vice President, Development and Membership BRE:"DA MYER.<;, Vice President, Marketing and Public Relation� DARA BROOKS, Director, Membership \ROLYI\ S. SMITH, Membership Coordinator TRACES OF INDIANA AND MIDWESTERN HISTORY RAY E. BOOMHOWER, Managing Editor GEORGF R. -

1 Sex Differences in Preferences for Humor Produced by Men Or Women: Is Humor in the Sex of the Perceiver? [Word Count = <25

1 Sex differences in preferences for humor produced by men or women: Is humor in the sex of the perceiver? [word count = <2500] Address correspondence to: 2 ABSTRACT It is a common argument that men are funnier than women. Recently, this belief has received modest empirical support among evolutionary psychologists who argue that humor results from sexual selection. Humor signals intelligence, and women thus use humor to discriminate between potential mates. From this, it follows that in addition to men being skilled producers of humor, women should be skilled perceivers of humor. Extant research has focused on humor production; here we focus on humor perception. In three studies, men and women identified the most humorous professional comedian (Studies 1 and 2) or individual they know personally (Study 3). We found large sex differences. In all three studies, men overwhelmingly preferred humor produced by other men, whereas women showed smaller (study 1) or no (studies 2 and 3) sex preference. We discuss biological and cultural roots of humor in light of these findings. 3 Sex differences in humor perception: Is humor in the sex of the perceiver? Although sex differences in the ability to produce humor have been debated at least since the 17th century (Congreve, 1695/1761; for more recent discussion, see the dialog between Hitchens and Stanley, Hitchens, 2007; Stanley, 2007), surprisingly few empirical studies exist on the topic. Yet understanding any sex difference in humor production or perception is important, since research suggests that humor mediates crucial social, psychological, and physiological processes. Socially, humor performs invaluable roles in persuasion (Mulkay, 1988) and managing personal relationships (Shiota, Campos, Keltner, & Hertenstein, 2004). -

Tom Hanks Halle Berry Martin Sheen Brad Pitt Robert Deniro Jodie Foster Will Smith Jay Leno Jared Leto Eli Roth Tom Cruise Steven Spielberg

TOM HANKS HALLE BERRY MARTIN SHEEN BRAD PITT ROBERT DENIRO JODIE FOSTER WILL SMITH JAY LENO JARED LETO ELI ROTH TOM CRUISE STEVEN SPIELBERG MICHAEL CAINE JENNIFER ANISTON MORGAN FREEMAN SAMUEL L. JACKSON KATE BECKINSALE JAMES FRANCO LARRY KING LEONARDO DICAPRIO JOHN HURT FLEA DEMI MOORE OLIVER STONE CARY GRANT JUDE LAW SANDRA BULLOCK KEANU REEVES OPRAH WINFREY MATTHEW MCCONAUGHEY CARRIE FISHER ADAM WEST MELISSA LEO JOHN WAYNE ROSE BYRNE BETTY WHITE WOODY ALLEN HARRISON FORD KIEFER SUTHERLAND MARION COTILLARD KIRSTEN DUNST STEVE BUSCEMI ELIJAH WOOD RESSE WITHERSPOON MICKEY ROURKE AUDREY HEPBURN STEVE CARELL AL PACINO JIM CARREY SHARON STONE MEL GIBSON 2017-18 CATALOG SAM NEILL CHRIS HEMSWORTH MICHAEL SHANNON KIRK DOUGLAS ICE-T RENEE ZELLWEGER ARNOLD SCHWARZENEGGER TOM HANKS HALLE BERRY MARTIN SHEEN BRAD PITT ROBERT DENIRO JODIE FOSTER WILL SMITH JAY LENO JARED LETO ELI ROTH TOM CRUISE STEVEN SPIELBERG CONTENTS 2 INDEPENDENT | FOREIGN | ARTHOUSE 23 HORROR | SLASHER | THRILLER 38 FACTUAL | HISTORICAL 44 NATURE | SUPERNATURAL MICHAEL CAINE JENNIFER ANISTON MORGAN FREEMAN 45 WESTERNS SAMUEL L. JACKSON KATE BECKINSALE JAMES FRANCO 48 20TH CENTURY TELEVISION LARRY KING LEONARDO DICAPRIO JOHN HURT FLEA 54 SCI-FI | FANTASY | SPACE DEMI MOORE OLIVER STONE CARY GRANT JUDE LAW 57 POLITICS | ESPIONAGE | WAR SANDRA BULLOCK KEANU REEVES OPRAH WINFREY MATTHEW MCCONAUGHEY CARRIE FISHER ADAM WEST 60 ART | CULTURE | CELEBRITY MELISSA LEO JOHN WAYNE ROSE BYRNE BETTY WHITE 64 ANIMATION | FAMILY WOODY ALLEN HARRISON FORD KIEFER SUTHERLAND 78 CRIME | DETECTIVE -

The BG News November 8, 1979

Bowling Green State University ScholarWorks@BGSU BG News (Student Newspaper) University Publications 11-8-1979 The BG News November 8, 1979 Bowling Green State University Follow this and additional works at: https://scholarworks.bgsu.edu/bg-news Recommended Citation Bowling Green State University, "The BG News November 8, 1979" (1979). BG News (Student Newspaper). 3669. https://scholarworks.bgsu.edu/bg-news/3669 This work is licensed under a Creative Commons Attribution-Noncommercial-No Derivative Works 4.0 License. This Article is brought to you for free and open access by the University Publications at ScholarWorks@BGSU. It has been accepted for inclusion in BG News (Student Newspaper) by an authorized administrator of ScholarWorks@BGSU. The BT3 He ws Bowling "Green 'Stale University thurs- Grants to aid women, minority grads day n-8-79 by Paul O'Donnell "We are trying to increase the pool of Staff reporter University among top-funded institutions qualified minority students," he said. The proposal for next year has Freshman loses The University has received $140,400 STONE SAID the federal funds will plementation of an effective graduate standing of each individual graduate already been submitted, and Stone said in grants from the Department of allow for 18 fellowships this year: two program. student, he noted. The areas of study he has requested added support. bid for mayor Health, Education and Welfare (HEW) in mathematics, seven in biological are identified by the University in the He said he hopes to obtain three more to assist minority and women students sciences, five in graduate business ad- HE WAS required to develop a writ- proposal submitted to HEW. -

Skelton United Nations Concert, February 27, 1968

CBS Television Network Press Information, 51 West 52 Street, New York, N.Y.10019 February 21, 1968 VICE PRESIDENT HUMPHREY TO INTRODUCE RED SKELTON'S SPECIAL PROGRAM FEB. 27 "Laughter - The Universal Language, 11 Skelton 1 s Pantomime Concert, Performed Before International U.N. Diplomatic Audience in New York Vice President Hubert H. Humphrey introduces Red Skelton and welcomes his distinguished audience of United Nations diplomats to 11 Laughter- The Universal Language," Skelton's pantomime concert to be broadcast on "The Red Skelton Hour 11 Tuesday, Feb. 27 (8:30-9:30 PM, EST) in color on the CBS Television Network. The Vice President taped his introductory remarks in Washington on Wednesday, Feb. 21 as a preface for the pantomime concert. The con cert itself was taped the previous night in New York before a black-tie audience representing 73 missions at the United Nations. Mr. Humphrey was unable to attend the New York performance because of Washington commitments. 11 Laughter - The Universal Language 11 is performed by Skelton without dialogue, except for the announcer 1 s spoken introductions, which are in English and French. Following the taping of the broadcast, Skelton and Mrs . Skelton greeted the diplomatic audience at a formal reception tendered by the (More) '. CBS Television Network 2 CBS Television Network and the United Nation: Association -U.S.A. at the Plaza Hotel in New York. In the receiving line with the Skeltons were Thomas H. Dawson, President of the CBS Television Network, and Mrs. Dawson; Oscar A. deLima, Chairman of the Executive Committee of the United Nations Asso ciation, and Mrs. -

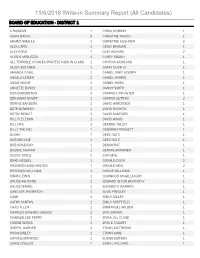

11/6/2018 Write-In Summary Report (All Candidates) BOARD of EDUCATION - DISTRICT 1

11/6/2018 Write-in Summary Report (All Candidates) BOARD OF EDUCATION - DISTRICT 1 A RAINEAR 1 CHRIS MURRAY 1 ADAM HATCH 2 CHRISTINE ASHOO 1 AHMED SMALLS 1 CHRISTINE KUSHNER 2 ALEX CARR 1 CINDY BEAMAN 1 ALEX FORD 1 CLAY WILKINS 2 ALICE E VERLEZZA 1 COREY BRUSH 1 ALL TERRIBLE CHOICES PROTECT KIDS IN CLASS 1 CYNTHIA WOOLARD 1 ALLEN BUTCHER 1 DAFFY DUCK III 1 AMANDA GOWL 1 DANIEL GREY SCURRY 1 ANGELA LEISER 2 DANIEL HARRIS 1 ANGIE WIGHT 1 DANIEL HORN 1 ANNETTE BUSBY 1 DANNY SMITH 1 BEN DOBERSTEIN 2 DAPHNE LANCASTER 1 BENJAMIN DOVER 1 DAPHNE SUTTON 2 BERNIE SANDERS 1 DAVID HARDISTER 1 BETH BOWMAN 1 DAVID RUNYON 1 BETSY BENOIT 1 DAVID SANFORD 1 BILL FLELEHAN 1 DAVID WOOD 1 BILL NYE 1 DEANNE TALLEY 1 BILLY THE KID 1 DEBORAH PRICKETT 1 BLANK 7 DEEZ NUTS 1 BOB MELONE 1 DEEZ NUTZ 1 BOB SPAZIANO 1 DEMOCRAT 1 BOBBIE CAVNAR 1 DENNIS BRAWNER 1 BOBBY JONES 1 DON MIAL 1 BRAD HESSEL 1 DONALD DUCK 2 BRANDON WASHINGTON 1 DONALD MIAL 2 BRANNON WILLIAMS 1 DONNE WILLIAMS 1 BRIAN LEWIS 1 DURWOOD MCGILLACUDY 1 BRUCE ASHFORD 1 EDWARD ALTON HUNTER IV 1 BRUCE MAMEL 1 ELIZABETH WARREN 1 CANDLER THORNTON 1 ELVIS PRESLEY 1 CASH 1 EMILY JOLLEY 1 CATHY SANTOS 1 EMILY SHEFFIELD 1 CHAD ALLEN 1 EMMANUEL WILDER 1 CHARLES EDWARD CHEESE 1 ERIC BROWN 1 CHARLES LEE PERRY 1 ERIKA JILL CLOSE 1 CHERIE WIGGS 1 ERIN E O'LEARY 1 CHERYL GARNER 1 ETHAN MATTHEWS 1 CHRIS BAILEY 1 ETHAN SIMS 1 CHRIS BJORNSTED 1 EUSHA BURTON 1 CHRIS COLLUM 1 EVAN L POLLARD 1 11/6/2018 Write-in Summary Report (All Candidates) BOARD OF EDUCATION - DISTRICT 1 EVERITT 1 JIMMY ALSTON 1 FELIX KEYES 1 JO ANNE -

ED WYNN "The Fire Chief" Publication of the Old Time Radio Club

Established 1975 Number 279 April 2000 ED WYNN "The Fire Chief" Publication of the Old Time Radio Club Membership Information Club Officers and Librarians New member processing, $5 plus club member President ship of $17.50 per year from January 1 to Jerry Collins (716) 683-6199 December 31. Members receive a tape library list 56 Christen Ct. ing, reference library listing and a monthly newslet Lancaster, NY 14086 ter. Memberships are as follows: if you join January-March, $17.50; April-June, $14; July Vice President & Canadian Branch September, $10; October-December, $7. All Richard Simpson renewals should be sent in as soon as possible to 960 16 Road R.R. 3 avoid missing issues. Please be sure to notify us if Fenwick, Ontario you have a change of address. The Old Time Canada, LOS 1CO Radio Club meets the first Monday of every month at 7:30 PM during the months of September to Treasurer, Back Issues, Videos & Records June at 393 George Urban Blvd., Cheektowaga, NY Dominic Parisi (716) 884-2004 14225. The club meets informally during the 38 Ardmore PI. months of July and August at the same address. Buffalo, NY 14213 Anyone interested in the Golden Age of Radio is welcome. The Old Time Radio Club is affiliated Membership Renewals, Change of Address, with The Old Time Radio Network. Cassette Library - #2000 and YR. Illustrated Press Cover Designs Club Mailing Address .Peter Bellanca (716) 773-2485 Old Time Radio Club 1620 Ferry Road 56 Christen Ct. Grand Island, NY 14072 Lancaster, NY 14086 Membership Inquires and OTR Network Related Items Back issues of The IllustratedPress are $1.50 post Richard Olday (716) 684-1604 paid. -

Indiana Genealogist Vol

INDIANA GENEALOGIST Vol. 24 No. 1 March 2013 1882 Indiana Doctors’ Death Notices Online Genealogy Education Pulaski County 1851 School Enumeration Miami County DivorcesSisters of St. Francis at Oldenburg, 1901 Notices from Allen, Harrison, Marion, Monroe, Vigo, & Washington Counties INDIANA GENEALOGICAL SOCIETY CONTENTS P. O. Box 10507 Ft. Wayne, IN 46852-0507 4 Editor’s Branch www.indgensoc.org Indiana Genealogist (ISSN 1558-0458) is pub- 5 Death Notices for Indiana Doctors (1882), lished electronically each quarter (March, submitted by Meredith Thompson June, September, and December) and is avail- able exclusively to members of the Indiana Genealogical Society as a benefit of member- 7 “The Whole Business is Right Here in This Spicy ship. Column”: Statewide News from the Indianapolis Sun, 20 November 1890, submitted by Rachel M. Popma EDITOR Rachel M. Popma E-mail: [email protected] 9 Muster Roll of First Lt. John Nilson, Company G, Twenty-fifth Indiana Regiment of Veteran Volunteers SUBMISSIONS Stationed Near Cheraw, SC, 28 February 1865, Submissions concerning people who were submitted by Tony Strobel in Indiana at one time are always welcome. Material from copyright-free publications is preferred. For information on accepted file 15 IN-GENious! Online Opportunities for Genealogy formats, please contact the editor. Education, by Rachel M. Popma WRITING AWARD Northwest District The Indiana Genealogical Society may bestow the Elaine Spires Smith Family History Writ- 19 1851 Enumeration of Children in School District ing Award (which includes $500) to the writer No. 2, Pulaski County, submitted by Janet Onken of an outstanding article that is submitted to either Indiana Genealogist or IGS Newsletter. -

"Command Performance"

“Command Performance” (Episode No. 21)—Bob Hope, Master of Ceremonies (July 7, 1942) Added to the National Registry: 2005 Essay by Cary O’Dell Bob Hope Soldiers line up for a “Command Performance” performance Radio’s unique “Command Performance” series was the brainchild of producer Louis G. Cowan. Cowan had joined the radio division of the US War Department just prior to the Japanese bombing of Pearl Harbor. With the commencement of the war though, Cowan found his job suddenly changed: rather than producing shows for civilians, he now found himself charged with creating programs for thousands of new servicemen stationed all around the globe. So he happened upon an idea. Many new members of the armed forces were no doubt having to quickly and awkwardly adjust to their new regimented military existence, to the myriad of commands and orders they now had to obey. What would happen if, instead of taking commands, they were allowed to give them, at least in terms of entertainment? Similar in nature to TV’s later “You Asked For It!,” Cowan’s “Command Performance” would solicit requests from servicemen the world over and ask them what they wanted to hear over the air. Cowan and his radio staff would then do their best to make it happen for them. From the beginning, to show their support for the troops, performers of all types (recruited via letters and ads in “Variety”) were generous with their time and talents. And both CBS and NBC donated their studios and recording facilities to the production. Even the major unions and show business guilds relaxed their rules in order to do these shows for the war effort (with the caveat that the shows be heard only by military personnel).