Alvin Theater

Total Page:16

File Type:pdf, Size:1020Kb

Load more

Recommended publications

-

1968.10.16.Pdf (8.470Mb)

_ Flt h ? - The Salis bur1 Stat'e ... occer ~(' - R cord _ ow .. Outten's 3-1-2 A nswers" Png 3! foJ:xXXVIII - NO. 2 OCTOBER 16, 196 FAI .Y '' TO y PL 0 s C. l\lr. \Vilson haron Leo nard, a senior, as Eliza Doolittle; John O'Ma y, also a sen io r, as Henry Higgins; Ike F eath er, a sophomore, as Colonel Pick in g is a n 1 I rly eli ng ; Frank Parks, a junior, as man who a ·ls Ml ll1 <' h ::u·acl t ' F'reddy Eynsford-Hill ; and Tom I al11. n c I lwC'r n J·~liza :mcl Hig Davis, a freshman, as Alfred P . g in s. Hr is the •pi Lom of lhc old Doolittle. gng ll sh grnllc•ma n." Fl"anlc Parks, who plays Fr ddy Eynsfor l-Hill, has b n in lh SSC proclu lions of arni v:tl and Com Alexander .Scourby Presents Program (• lly of J~rron; and in lh student produ lion Phoenix Too F r - A noted actor of stage, scr een, <1111·111. He a lso di!" • lr cl L ('t 'l'hrrl' radio and television came to lk 1"::trc·(• las l y 111·. cscl"ibin g I hr alisbury State College on Thurs r; hara :ler of l•' n ·clcl y, h<' said , day, October 3, 1968, in H olloway "F1·rclcl y iH an a1" islocn1li ·. s liff Hall Auditorium when Alexander 'CJli a 1· young 111 :1_11 wilh a l finilc courby presented " Walt Whit cl a mpne>ss b hincl llw cars. -

AMERICAN VETERANS of ISRAEL VOLUNTEERS in ISRAEL’S WAR of INDEPENDENCE UNITED STATES & CANADA VOLUNTEERS 136 East 39Th Street, New York, NY 10016

SPRING 2005 AMERICAN VETERANS OF ISRAEL VOLUNTEERS IN ISRAEL’S WAR OF INDEPENDENCE UNITED STATES & CANADA VOLUNTEERS 136 East 39th Street, New York, NY 10016 THE MIGHTY MA’OZ Sharon Recalls Machal before American Part I From Pleasure Ship to Flagship. Jewish Leaders in New York, May 22 By J. Wandres Following is an excerpt from Sharon’s address: By October 948, the Israeli I am honored to stand here and feel the strong bond between Israel Defence Force had pushed back Arab and the rest of the Jewish world. We share a history, and we share a future as forces to the north and east. Egyptian well. forces had been halted in the Negev. In 948, the new State of Israel was forced to stand its ground against Only Israel’s Mediterranean coastline the armies of the combined Arab world. The survival of Israel was not at all remained vulnerable. An Egyptian certain. We had no choice but to fight for our lives. It seemed as if we stood squadron, chased from Tel Aviv, was alone. about to be dealt with at Gaza. Kvar- But we were not all alone. I had the merit to participate in the War of nit (Commander) Paul Shulman, on the Independence, and I still remember how I felt when I learned that volunteers bridge of the 690-ton, 20-foot-long K- from Jewish communities around the world were coming to help us. They 24 Ma’oz that day in mid-October, was risked, and sometimes lost, their lives in our War of Independence. -

IGOR GOLDIN Director, Sdc Contact: Ronald Gwiazda 718-809-3068 Abrams Artists Agency [email protected] 646-461-9325 [email protected]

IGOR GOLDIN director, sdc Contact: Ronald Gwiazda 718-809-3068 Abrams Artists Agency [email protected] 646-461-9325 [email protected] OFF-BROADWAY YANK! YORK THEATRE COMPANY book & lyrics by David Zellnik, music by Joseph Zellnik md: John Baxindine choreo: Jeffry Denman *Drama Desk Award nomination - OUTSTANDING DIRECTOR OF A MUSICAL *SDC Joe A. Callaway finalist for DISTINGUISHED DIRECTION WITH GLEE PROSPECT THEATRE COMPANY book, music & lyrics by John Gregor md: Daniel Feyer choreo: Antoinette DiPietropolo *New York Times Critics Pick *BEST STAGING OF A BIG NUMBER IN A PUNY SPACE, New York Times year end list A RITUAL OF FAITH EMERGING ARTISTS by Brad Levinson OTHER NYC & REGIONAL WEST SIDE STORY ENGEMAN THEATRE at NORTHPORT book by Arthur Laurents, music by Leonard Bernstein, lyrics by Stephen Sondheim md: James Olmstead choreo: Jeffry Denman SWEENEY TODD MERRY-GO-ROUND, FINGER LAKES, NY music & lyrics by Stephen Sondheim, book by Hugh Wheeler md: Jeff Theiss BABY INFINITY THEATRE, ANNAPOLIS, MD book by Sybille Pearson, music by David Shire, lyrics by Richard Maltby, Jr. md: Jeffrey Lodin THE PRODUCERS ENGEMAN THEATER at NORTHPORT book by Mel Brooks & Thomas Meehan, music & lyrics by Mel Brooks md: James Olmstead choreo: Antoinette DiPietropolo JANE AUSTEN’S PRIDE AND PREJUDICE a musical McCOY/RIGBY ENTERTAINMENT/ book, music & lyrics by Lindsay Warren Baker and Amanda Jacobs LA MIRADA, CA md: Timothy Splain choreo: Jeffry Denman TICK, TICK…BOOM! AMERICAN THEATRE GROUP, NJ book, music & lyrics by Jonathan Larson, David -

Stanley Chase Papers LSC.1090

http://oac.cdlib.org/findaid/ark:/13030/kt6h4nc876 No online items Finding Aid for the Stanley Chase Papers LSC.1090 Processed by Timothy Holland and Joshua Amberg in the Center For Primary Research and Training (CFPRT), with assistance from Laurel McPhee, Fall 2005; machine-readable finding aid created by Caroline Cubé and edited by Josh Fiala, Caroline Cubé, Laurel McPhee and Amy Shung-Gee Wong. UCLA Library Special Collections Online finding aid last updated on 2020 December 11. Room A1713, Charles E. Young Research Library Box 951575 Los Angeles, CA 90095-1575 [email protected] URL: https://www.library.ucla.edu/special-collections Finding Aid for the Stanley Chase LSC.1090 1 Papers LSC.1090 Contributing Institution: UCLA Library Special Collections Title: Stanley Chase papers Creator: Chase, Stanley Identifier/Call Number: LSC.1090 Physical Description: 157.2 Linear Feet(105 boxes, 12 oversize boxes, 27 map folders) Date (inclusive): circa 1925-2001 Date (bulk): 1955-1989 Abstract: Stanley Chase (1928-) was a theater, film, and television producer. The collection consists of production and business files, original production drawings, posters, press clippings, sound recordings, and scripts from his major projects. Stored off-site. All requests to access special collections material must be made in advance using the request button located on this page. Language of Material: Materials are in English. Conditions Governing Access Open for research. All requests to access special collections materials must be made in advance using the request button located on this page. Physical Characteristics and Technical Requirements CONTAINS AUDIOVISUAL MATERIALS: This collection contains both processed and unprocessed audiovisual materials. -

Program Notes

“Come on along, you can’t go wrong Kicking the clouds away!” Broadway was booming in the 1920s with the energy of youth and new ideas roaring across the nation. In New York City, immigrants such as George Gershwin were infusing American music with their own indigenous traditions. The melting pot was cooking up a completely new sound and jazz was a key ingredient. At the time, radio and the phonograph weren’t widely available; sheet music and live performances remained the popular ways to enjoy the latest hits. In fact, New York City’s Tin Pan Alley was overflowing with "song pluggers" like George Gershwin who demonstrated new tunes to promote the sale of sheet music. George and his brother Ira Gershwin composed music and lyrics for the 1927 Broadway musical Funny Face. It was the second musical they had written as a vehicle for Fred and Adele Astaire. As such, Funny Face enabled the tap-dancing duo to feature new and well-loved routines. During a number entitled “High Hat,” Fred sported evening clothes and a top hat while tapping in front of an enormous male chorus. The image of Fred during that song became iconic and versions of the routine appeared in later years. The unforgettable score featured such gems as “’S Wonderful,” “My One And Only,” “He Loves and She Loves,” and “The Babbitt and the Bromide.” The plot concerned a girl named Frankie (Adele Astaire), who persuaded her boyfriend Peter (Allen Kearns) to help retrieve her stolen diary from Jimmie Reeve (Fred Astaire). However, Peter pilfered a piece of jewelry and a wild chase ensued. -

KS5 Exploring Performance Styles in Musical Theatre

Exploring performance KS5 styles in Musical Theatre Heidi McEntee Heidi McEntee is a Dance and KS5 – BTEC LEVEL 3, UNIT D10 Performing Arts specialist based in the Midlands. She has worked in education for over fifteen years delivering a variety of Dance and Performing Arts qualifications at Introduction Levels 1, 2 and 3. She is a Senior Unit D10: Exploring Performance Styles is one of the three units which sit within Module D: Assessment Associate working on musical theatre Skills Development from the new BTEC Level 3 in Performing Arts Practice Performing Arts qualifications and (musical theatre) qualification. This scheme of work focuses on the first unit which introduces a contributing author for student and explores different musical theatre styles. revision guides. This unit requires learners to develop their practical skills in dance, acting and singing while furthering their understanding of musical theatre styles. The unit culminates in a performance of two extracts in two different styles of musical theatre as well as a critical review of the stylistic qualities within these extracts. This scheme of work provides a suggested approach to six weeks of introductory classes, as a part of a full timetable, which explores the development of performance styles through the history of musical theatre via practical activities, short projects and research tasks. Learning objectives By the end of this scheme, learners will have: § Investigated the history of musical theatre and the factors which have influenced its development Unit D10: Exploring Performance § Explored the characteristics of different musical theatre styles and how they have developed Styles from BTEC L3 Nationals over time Performing Arts Practice (musical § Applied stylistic conventions to the performance of material theatre) (2019) § Examined professional work through critical analysis. -

The Shubert Foundation 2020 Grants

The Shubert Foundation 2020 Grants THEATRE About Face Theatre Chicago, IL $20,000 The Acting Company New York, NY 80,000 Actor's Express Atlanta, GA 30,000 The Actors' Gang Culver City, CA 45,000 Actor's Theatre of Charlotte Charlotte, NC 30,000 Actors Theatre of Louisville Louisville, KY 200,000 Adirondack Theatre Festival Glens Falls, NY 25,000 Adventure Theatre Glen Echo, MD 45,000 Alabama Shakespeare Festival Montgomery, AL 165,000 Alley Theatre Houston, TX 75,000 Alliance Theatre Company Atlanta, GA 220,000 American Blues Theater Chicago, IL 20,000 American Conservatory Theater San Francisco, CA 190,000 American Players Theatre Spring Green, WI 50,000 American Repertory Theatre Cambridge, MA 250,000 American Shakespeare Center Staunton, VA 30,000 American Stage Company St. Petersburg, FL 35,000 American Theater Group East Brunswick, NJ 15,000 Amphibian Stage Productions Fort Worth, TX 20,000 Antaeus Company Glendale, CA 15,000 Arden Theatre Company Philadelphia, PA 95,000 Arena Stage Washington, DC 325,000 Arizona Theatre Company Tucson, AZ 50,000 Arkansas Arts Center Children's Theatre Little Rock, AR 20,000 Ars Nova New York, NY 70,000 Artists Repertory Theatre Portland, OR 60,000 Arts Emerson Boston, MA 30,000 ArtsPower National Touring Theatre Cedar Grove, NJ 15,000 Asolo Repertory Theatre Sarasota, FL 65,000 Atlantic Theater Company New York, NY 200,000 Aurora Theatre Lawrenceville, GA 30,000 Aurora Theatre Company Berkeley, CA 40,000 Austin Playhouse Austin, TX 20,000 Azuka Theatre Philadelphia, PA 15,000 Barrington Stage Company -

C 170112 ZSM: 242 West 53Rd Street Parking Garage

CITY PLANNING COMMISSION May 24, 2017 / Calendar No. 12 C 170112 ZSM IN THE MATTER OF an application submitted by Roseland Development Associates LLC pursuant to Sections 197-c and 201 of the New York City Charter for the grant of a special permit pursuant to Section 13-45 (Special Permits for Additional Parking Spaces) and Section 13-451 (Additional parking spaces for residential growth) of the Zoning Resolution to allow an attended public parking garage with a maximum capacity of 184 spaces on portions of the ground floor, cellar, and subcellar levels of a proposed mixed-use building on property located at 242 West 53rd Street (Block 1024, Lots 52 and 7), in C6-5 and C6-7 Districts, within the Special Midtown District (Theater Subdistrict), Borough of Manhattan, Community District 5. This application for a special permit was filed by Roseland Development Associates LLC on September 30, 2016. The special permit would facilitate the provision of an additional 95 parking spaces, for a total of 184 parking spaces, within a public parking garage in a mixed-use development at 242 West 53rd Street within the Theater Subdistrict of the Special Midtown District in Manhattan Community District 5. BACKGROUND 242 West 53rd Street is a through lot consisting of two tax lots on one zoning lot (Block 1024, Lots 52 and 7) located in the middle of the block bounded by Eighth Avenue, Broadway, West 52nd Street and West 53rd Street. The development site (Lot 52) is a “U”-shaped lot that totals 29,196 square feet in area and has 225 feet of frontage on West 53rd Street and 65.75 feet of total frontage, in two parts, on West 52nd Street. -

2018 Annual Report

Annual Report 2018 Dear Friends, welcome anyone, whether they have worked in performing arts and In 2018, The Actors Fund entertainment or not, who may need our world-class short-stay helped 17,352 people Thanks to your generous support, The Actors Fund is here for rehabilitation therapies (physical, occupational and speech)—all with everyone in performing arts and entertainment throughout their the goal of a safe return home after a hospital stay (p. 14). nationally. lives and careers, and especially at times of great distress. Thanks to your generous support, The Actors Fund continues, Our programs and services Last year overall we provided $1,970,360 in emergency financial stronger than ever and is here for those who need us most. Our offer social and health services, work would not be possible without an engaged Board as well as ANNUAL REPORT assistance for crucial needs such as preventing evictions and employment and training the efforts of our top notch staff and volunteers. paying for essential medications. We were devastated to see programs, emergency financial the destruction and loss of life caused by last year’s wildfires in assistance, affordable housing, 2018 California—the most deadly in history, and nearly $134,000 went In addition, Broadway Cares/Equity Fights AIDS continues to be our and more. to those in our community affected by the fires and other natural steadfast partner, assuring help is there in these uncertain times. disasters (p. 7). Your support is part of a grand tradition of caring for our entertainment and performing arts community. Thank you Mission As a national organization, we’re building awareness of how our CENTS OF for helping to assure that the show will go on, and on. -

View the Playbill

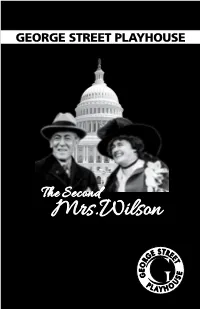

GEORGE STREET PLAYHOUSE The Second Mrs.Wilson Board of Trustees Chairman: James N. Heston* President: Dr. Penelope Lattimer* First Vice President: Lucy Hughes* Second Vice President: Janice Stolar* Treasurer: David Fasanella* Secretary: Sharon Karmazin* Ronald Bleich David Saint* David Capodanno Jocelyn Schwartzman Kenneth M. Fisher Lora Tremayne William R. Hagaman, Jr. Stephen M. Vajtay Norman Politziner Alan W. Voorhees Kelly Ryman* *Denotes Members of the Executive Committee Trustees Emeritus Robert L. Bramson Cody P. Eckert Clarence E. Lockett Al D’Augusta Peter Goldberg Anthony L. Marchetta George Wolansky, Jr. Honorary Board of Trustees Thomas H. Kean Eric Krebs Honorary Memoriam Maurice Aaron∆ Arthur Laurents∆ Dr. Edward Bloustein∆ Richard Sellars∆ Dora Center∆∆ Barbara Voorhees∆∆ Douglas Fairbanks, Jr.∆ Edward K. Zuckerman∆ Milton Goldman∆ Adelaide M. Zagoren John Hila ∆∆ – Denotes Trustee Emeritus ∆ – Denotes Honorary Trustee From the Artistic Director It is a pleasure to welcome back playwright Joe DiPietro for his fifth premiere here at George Street Playhouse! I am truly astonished at the breadth of his talent! From the wild farce of The Toxic Photo by: Frank Wojciechowski Avenger to the drama of Creating Claire and the comic/drama of Clever Little Lies, David Saint Artistic Director now running at the West Side Theatre in Manhattan, he explores all genres. And now the sensational historical romance of The Second Mrs.Wilson. The extremely gifted Artistic Director of Long Wharf Theatre, Gordon Edelstein, brings a remarkable company of Tony Award-winning actors, the top rank of actors working in American theatre today, to breathe astonishing life into these characters from a little known chapter of American history. -

ANTA Theater and the Proposed Designation of the Related Landmark Site (Item No

Landmarks Preservation Commission August 6, 1985; Designation List 182 l.P-1309 ANTA THFATER (originally Guild Theater, noN Virginia Theater), 243-259 West 52nd Street, Manhattan. Built 1924-25; architects, Crane & Franzheim. Landmark Site: Borough of Manhattan Tax Map Block 1024, Lot 7. On June 14 and 15, 1982, the Landmarks Preservation Commission held a public hearing on the proposed designation as a Landmark of the ANTA Theater and the proposed designation of the related Landmark Site (Item No. 5). The hearing was continued to October 19, 1982. Both hearings had been duly advertised in accordance with the provisions of law. Eighty-three witnesses spoke in favor of designation. Two witnesses spoke in opposition to designation. The owner, with his representatives, appeared at the hearing, and indicated that he had not formulated an opinion regarding designation. The Commission has received many letters and other expressions of support in favor of this designation. DESCRIPTION AND ANALYSIS The ANTA Theater survives today as one of the historic theaters that symbolize American theater for both New York and the nation. Built in the 1924-25, the ANTA was constructed for the Theater Guild as a subscription playhouse, named the Guild Theater. The fourrling Guild members, including actors, playwrights, designers, attorneys and bankers, formed the Theater Guild to present high quality plays which they believed would be artistically superior to the current offerings of the commercial Broadway houses. More than just an auditorium, however, the Guild Theater was designed to be a theater resource center, with classrooms, studios, and a library. The theater also included the rrost up-to-date staging technology. -

Peter Bergson:” Historical Memory and a Forgotten Holocaust Hero

Making “Peter Bergson:” Historical Memory and a Forgotten Holocaust Hero By Emily J. Horne B.A. May 2000, The George Washington University A Thesis submitted to The Faculty of Columbian College of Arts and Sciences of The George Washington University in partial satisfaction of the requirements for the degree of Master of Arts January 31, 2009 Thesis directed by Dina R. Khoury Associate Professor of History and International Affairs For my parents, Pamela and Stephen, and for my sister, Jennifer… who remind me every day to seek out “story potential.” ii Acknowledgements I am endlessly indebted to my brilliant committee members. Dina Khoury first introduced me to memory studies at the beginning of my graduate career and I would not have finished this process without her guidance, enthusiasm and advice. Many thanks to Walter Reich for all his anecdotes and legends that never appeared in the history books, and for calming me down when the work seemed overwhelming. Every young woman graduate student should be lucky enough to have a role model like Hope Harrison, who first introduced me to the twin joys of contemporary Holocaust memory and spargel season in Berlin. I have been deeply privileged to have these three scholars as readers and advisers for this thesis. Also from the GWU History Department I would like to thank Leo Ribuffo, who taught the first history class of my undergraduate career and inspired me to stay for another eight years. Director Geri Rypkema of the Office of Graduate Assistantships and Fellowships has been a wonderful supervisor and friend through much of my graduate career.