Countering Violent Extremism (CVE) Subcommittee

Total Page:16

File Type:pdf, Size:1020Kb

Load more

Recommended publications

-

Center for American Progress Action Fund

CENTER FOR AMERICAN PROGRESS THE TRAGEDY OF OKLAHOMA CITY 15 YEARS LATER AND THE LESSONS FOR TODAY WELCOME: AL FROM, FOUNDER, DEMOCRATIC LEADERSHIP COUNCIL JOHN PODESTA, PRESIDENT AND CHIEF EXECUTIVE OFFICER, CENTER FOR AMERICAN PROGRESS ACTION FUND INTRODUCTION: MICHAEL REYES, FORMER EMPLOYEE, ALFRED P. MURRAH FEDERAL BUILDING SPEAKER: PRESIDENT WILLIAM J. CLINTON MODERATOR: RON BROWNSTEIN, POLITICAL DIRECTOR, ATLANTIC MEDIA PANELISTS: REP. KENDRICK MEEK (D-FL) MARVIN “MICKEY” EDWARDS (R-OK), FORMER U.S. REPRESENTATIVE MICHAEL WALDMAN, EXECUTIVE DIRECTOR, BRENNAN CENTER FOR JUSTICE, NEW YORK UNIVERSITY LAW SCHOOL MARK POTOK, DIRECTOR OF INTELLIGENCE PROJECTS, SOUTHERN POVERTY LAW CENTER JAMIE GORELICK, CHAIR, DEFENSE, NATIONAL SECURITY AND GOVERNMENT CONTRACTS PRACTICE GROUP, WILMERHALE BRADLEY BUCKLES, FORMER DIRECTOR, U.S. BUREAU OF ALOCHOL, TOBACCO AND FIREARMS FRIDAY, APRIL 16, 2010 WASHINGTON, D.C. Transcript by Federal News Service Washington, D.C. JOHN PODESTA: Good morning, everyone. I’m John Podesta. I’m the president of the Center for American Progress Action Fund. I want to thank you for joining us here today to remember and to reflect on the tragedy that occurred in Oklahoma City nearly 15 years ago. There are days that punctuate all our memories, collectively and as a country, and April 19, 1995 is most certainly one of them. So despite the somberness of this occasion, I’m honored to co-host this important event today and I’m grateful to those who were affected for taking the time to share their experiences, as we look both backwards to remember what happened and forward to draw lessons. We can now see more clearly from today’s vantage point. -

Executive Branch

EXECUTIVE BRANCH THE PRESIDENT BARACK H. OBAMA, Senator from Illinois and 44th President of the United States; born in Honolulu, Hawaii, August 4, 1961; received a B.A. in 1983 from Columbia University, New York City; worked as a community organizer in Chicago, IL; studied law at Harvard University, where he became the first African American president of the Harvard Law Review, and received a J.D. in 1991; practiced law in Chicago, IL; lecturer on constitutional law, University of Chicago; member, Illinois State Senate, 1997–2004; elected as a Democrat to the U.S. Senate in 2004; and served from January 3, 2005, to November 16, 2008, when he resigned from office, having been elected President; family: married to Michelle; two children: Malia and Sasha; elected as President of the United States on November 4, 2008, and took the oath of office on January 20, 2009. EXECUTIVE OFFICE OF THE PRESIDENT 1600 Pennsylvania Avenue, NW., 20500 Eisenhower Executive Office Building (EEOB), 17th Street and Pennsylvania Avenue, NW., 20500, phone (202) 456–1414, http://www.whitehouse.gov The President of the United States.—Barack H. Obama. Special Assistant to the President and Personal Aide to the President.— Anita Decker Breckenridge. Director of Oval Office Operations.—Brian Mosteller. OFFICE OF THE VICE PRESIDENT phone (202) 456–1414 The Vice President.—Joseph R. Biden, Jr. Assistant to the President and Chief of Staff to the Vice President.—Bruce Reed, EEOB, room 276, 456–9000. Deputy Assistant to the President and Chief of Staff to Dr. Jill Biden.—Sheila Nix, EEOB, room 200, 456–7458. -

FBI Academy Training Facility A&E Study………………………………

Table of Contents Page No. I. Overview ………………………………………………………………….............. 1-1 II. Summary of Program Changes…………………………………………….. 2-1 III. Appropriations Language and Analysis of Appropriations Language….......... 3-1 IV. Decision Unit Justification…………………………………………………... 4-1 A. Intelligence………………………………………………………………… . 4-1 1. Program Description 2. Performance Tables 3. Performance, Resources, and Strategies a. Performance Plan and Report for Outcomes b. Strategies to Accomplish Outcomes B. Counterterrorism/Counterintelligence ……………………………………… 4-14 1. Program Description 2. Performance Tables 3. Performance, Resources, and Strategies a. Performance Plan and Report for Outcomes b. Strategies to Accomplish Outcomes C. Criminal Enterprises and Federal Crimes…………………………………… 4-36 1. Program Description 2. Performance Tables 3. Performance, Resources, and Strategies a. Performance Plan and Report for Outcomes b. Strategies to Accomplish Outcomes D. Criminal Justice Services…………………………………………………….. 4-59 1. Program Description 2. Performance Tables 3. Performance, Resources, and Strategies a. Performance Plan and Report for Outcomes b. Strategies to Accomplish Outcomes V. Program Increases by Item………………………………………………… 5-1 Domain and Operations Increases Comprehensive National Cybersecurity Initiative………………………... 5-1 Intelligence Program………………………………………………….…... 5-6 National Security Field Investigations……….………………………….... 5-13 Mortgage Fraud and White Collar Crime………………………………… 5-15 WMD Response………………………………………………………..…. 5-19 Infrastructure Increases -

Download DECEMBER 1964.Pdf

Vol. 33, No. 12 December 1964 Federal Bureau of Investigation United States Department of Justice J. Edgar Hoover, Director Index to l'olume 33, 1964 (p. 27) Contents 1 Message from Director J. Edgar Hoover Feature Article: 3 Recruiting and Training of Police Personnel, by Joseph T. Carroll, Chief of Police, Lincoln, Nebr. FBI National Academy: 9 Marine Commandant, Noted Editor Address Graduates Scientific Aids:· 13 BuildingMaterial Evidence in Burglary Cases Nationwide Crimescope: 17 A 2 Gauge Cane 17 From "Pen" to "Sword" Vol. 33, No. 12 Crime Prevention: 18 A Mess<'toe for Young People, by Edward K. Dabrowski, Sheriff of Bri tol County, New Bedford, Mass. Other Topics: 26 Wanted by the FBI 27 Index to Articles Published During 1964 Publi.hed by the FEDERAL BUREAU Identification: OF INVESTIGATION, Questionable Pattern (back cover) UNITED STATES DEPARTMENT OF JUSTICE Wa.hlngton, D.C. 20535 MESSAGE FROM THE DIRECTOR TO ALL LAW E FORCEMENT OFFICIALS ATHEISTIC COMMUNISM and the lawless underworld are not the only threats to the safety and welfare of our great Nation. Enemies of freedom come under many guises. Our society today is in a great state of unrest. Many citizens are confused and troubled. For the first time, some are confronted with issues and decisions relating to the rights and dignity of their fellow countrymen, problems which heretofore they had skirted or ignored. We have in our midst hatemongers, bigots, and riotous agitators, many of whom are at opposite poles philosophically but who spew similar doctrines of prejudice and intolerance. They exploit hate and fear for personal gain and selfaggrandizement. -

CVE and Constitutionality in the Twin Cities: How Countering Violent Extremism Threatens the Equal Protection Rights of American Muslims in Minneapolis-St

American University Law Review Volume 69 Issue 6 Article 6 2020 CVE and Constitutionality in the Twin Cities: How Countering Violent Extremism Threatens the Equal Protection Rights of American Muslims in Minneapolis-St. Paul Sarah Chaney Reichenbach American University Washington College of Law Follow this and additional works at: https://digitalcommons.wcl.american.edu/aulr Part of the Civil Rights and Discrimination Commons, Constitutional Law Commons, Law and Politics Commons, Law and Society Commons, President/Executive Department Commons, and the State and Local Government Law Commons Recommended Citation Reichenbach, Sarah Chaney (2020) "CVE and Constitutionality in the Twin Cities: How Countering Violent Extremism Threatens the Equal Protection Rights of American Muslims in Minneapolis-St. Paul," American University Law Review: Vol. 69 : Iss. 6 , Article 6. Available at: https://digitalcommons.wcl.american.edu/aulr/vol69/iss6/6 This Comment is brought to you for free and open access by the Washington College of Law Journals & Law Reviews at Digital Commons @ American University Washington College of Law. It has been accepted for inclusion in American University Law Review by an authorized editor of Digital Commons @ American University Washington College of Law. For more information, please contact [email protected]. CVE and Constitutionality in the Twin Cities: How Countering Violent Extremism Threatens the Equal Protection Rights of American Muslims in Minneapolis-St. Paul Abstract In 2011, President Barack Obama announced a national strategy for countering violent extremism (CVE) to attempt to prevent the “radicalization” of potential violent extremists. The Obama Administration intended the strategy to employ a community-based approach, bringing together the government, law enforcement, and local communities for CVE efforts. -

A FAILURE of INITIATIVE Final Report of the Select Bipartisan Committee to Investigate the Preparation for and Response to Hurricane Katrina

A FAILURE OF INITIATIVE Final Report of the Select Bipartisan Committee to Investigate the Preparation for and Response to Hurricane Katrina U.S. House of Representatives 4 A FAILURE OF INITIATIVE A FAILURE OF INITIATIVE Final Report of the Select Bipartisan Committee to Investigate the Preparation for and Response to Hurricane Katrina Union Calendar No. 00 109th Congress Report 2nd Session 000-000 A FAILURE OF INITIATIVE Final Report of the Select Bipartisan Committee to Investigate the Preparation for and Response to Hurricane Katrina Report by the Select Bipartisan Committee to Investigate the Preparation for and Response to Hurricane Katrina Available via the World Wide Web: http://www.gpoacess.gov/congress/index.html February 15, 2006. — Committed to the Committee of the Whole House on the State of the Union and ordered to be printed U. S. GOVERNMEN T PRINTING OFFICE Keeping America Informed I www.gpo.gov WASHINGTON 2 0 0 6 23950 PDF For sale by the Superintendent of Documents, U.S. Government Printing Office Internet: bookstore.gpo.gov Phone: toll free (866) 512-1800; DC area (202) 512-1800 Fax: (202) 512-2250 Mail: Stop SSOP, Washington, DC 20402-0001 COVER PHOTO: FEMA, BACKGROUND PHOTO: NASA SELECT BIPARTISAN COMMITTEE TO INVESTIGATE THE PREPARATION FOR AND RESPONSE TO HURRICANE KATRINA TOM DAVIS, (VA) Chairman HAROLD ROGERS (KY) CHRISTOPHER SHAYS (CT) HENRY BONILLA (TX) STEVE BUYER (IN) SUE MYRICK (NC) MAC THORNBERRY (TX) KAY GRANGER (TX) CHARLES W. “CHIP” PICKERING (MS) BILL SHUSTER (PA) JEFF MILLER (FL) Members who participated at the invitation of the Select Committee CHARLIE MELANCON (LA) GENE TAYLOR (MS) WILLIAM J. -

Sunday Morning Grid 2/8/15 Latimes.Com/Tv Times

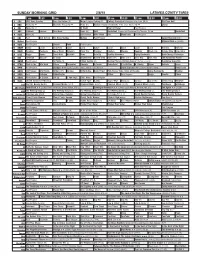

SUNDAY MORNING GRID 2/8/15 LATIMES.COM/TV TIMES 7 am 7:30 8 am 8:30 9 am 9:30 10 am 10:30 11 am 11:30 12 pm 12:30 2 CBS CBS News Sunday Face the Nation (N) Major League Fishing (N) College Basketball Michigan at Indiana. (N) Å PGA Tour Golf 4 NBC News (N) Å Meet the Press (N) Å News (N) Hockey Chicago Blackhawks at St. Louis Blues. (N) Å Skiing 5 CW News (N) Å In Touch Hour Of Power Paid Program 7 ABC Outback Explore This Week News (N) NBA Basketball Clippers at Oklahoma City Thunder. (N) Å Basketball 9 KCAL News (N) Joel Osteen Mike Webb Paid Woodlands Paid Program 11 FOX Paid Joel Osteen Fox News Sunday Midday Paid Program Larger Than Life ›› 13 MyNet Paid Program Material Girls › (2006) 18 KSCI Paid Program Church Faith Paid Program 22 KWHY Como Local Jesucristo Local Local Gebel Local Local Local Local Transfor. Transfor. 24 KVCR Painting Dewberry Joy of Paint Wyland’s Paint This Painting Kitchen Mexico Cooking Chefs Life Simply Ming Ciao Italia 28 KCET Raggs Space Travel-Kids Biz Kid$ News Asia Biz Healthy Hormones Aging Backwards BrainChange-Perlmutter 30 ION Jeremiah Youssef In Touch Bucket-Dino Bucket-Dino Doki (TVY) Doki (TVY7) Dive, Olly Dive, Olly The Karate Kid Part II 34 KMEX Paid Program Al Punto (N) Fútbol Central (N) Mexico Primera Division Soccer: Pumas vs Leon República Deportiva 40 KTBN Walk in the Win Walk Prince Carpenter Liberate In Touch PowerPoint It Is Written B. -

Microsoft 2012 Citizenship Report

Citizenship at Microsoft Our Company Serving Communities Working Responsibly About this Report Microsoft 2012 Citizenship Report Microsoft 2012 Citizenship Report 01 Contents Citizenship at Microsoft Serving Communities Working Responsibly About this Report 3 Serving communities 14 Creating opportunities for youth 46 Our people 85 Reporting year 4 Working responsibly 15 Empowering youth through 47 Compensation and benefits 85 Scope 4 Citizenship governance education and technology 48 Diversity and inclusion 85 Additional reporting 5 Setting priorities and 16 Inspiring young imaginations 50 Training and development 85 Feedback stakeholder engagement 18 Realizing potential with new skills 51 Health and safety 86 United Nations Global Compact 5 External frameworks 20 Supporting youth-focused 53 Environment 6 FY12 highlights and achievements nonprofits 54 Impact of our operations 23 Empowering nonprofits 58 Technology for the environment 24 Donating software to nonprofits Our Company worldwide 61 Human rights 26 Providing hardware to more people 62 Affirming our commitment 28 Sharing knowledge to build capacity 64 Privacy and data security 8 Our business 28 Solutions in action 65 Online safety 8 Where we are 67 Freedom of expression 8 Engaging our customers 31 Employee giving and partners 32 Helping employees make 69 Responsible sourcing 10 Our products a difference 71 Hardware production 11 Investing in innovation 73 Conflict minerals 36 Humanitarian response 74 Expanding our efforts 37 Providing assistance in times of need 76 Governance 40 Accessibility 77 Corporate governance 41 Empowering people with disabilities 79 Maintaining strong practices and performance 42 Engaging students with special needs 80 Public policy engagement 44 Improving seniors’ well-being 83 Compliance Cover: Participants at the 2012 Imagine Cup, Sydney, Australia. -

JAN 2017 KQED Perks

Member Magazine JAN 2017 KQED Perks 2-for-1 Tickets to PHOTOFAIRS Experience cutting-edge, contemporary artworks by emerging and internationally photography on a global scale. Don’t miss recognized artists working with still and the inaugural launch of PHOTOFAIRS moving images. For more information, visit San Francisco, January 27–29, at Fort photofairs.org. Mason’s Festival Pavilion. The new boutique fair, presenting prominent galleries from For special 2-for-1 ticket offer, enter around the world, is the West Coast’s leading promo code KQED: fortmason.org/ destination for discovering and collecting event/photofairs-san-francisco Free Admission to the de Young See Frank Stella: A Retrospective © 2016 Frank Stella / Artists Rights Society (ARS), New York. 1967. Polymer and fluorescent polymer paint on canvas, 120 x 240 in (308.4 609.6 cm). 1967. Polymer and fluorescent Harran II, Frank Stella, Since bursting into the New York art world On Friday, January 20, and Saturday, in 1959, Frank Stella has challenged and January 21, admission to the de Young expanded the definitions of painting and museum is free to KQED members who sculpture. Frank Stella: A Retrospective includes present a current KQED MemberCard 50 major works that span the artist’s career, and valid ID (up to two tickets per from his legendary early Black paintings through MemberCard). Tickets must be picked up his groundbreaking shaped canvases and relief on-site and are subject to availability. For constructions to recent sculptural works created hours, information about the exhibition and with cutting-edge digital technologies. On view more, visit deyoung.famsf.org. -

Election Insight 2020

ELECTION INSIGHT 2020 “This isn’t about – yeah, it is about me, I guess, when you think about it.” – President Donald J. Trump Kenosha Wisconsin Regional Airport Election Eve. 1 • Election Insight 2020 Contents 04 … Election Results on One Page 06 … Biden Transition Team 10 … Potential Biden Administration 2 • Election Insight 2020 Election Results on One Page 3 • Election Insight 2020 DENTONS’ DEMOCRATS Election Results on One Page “The waiting is the hardest part.” Election results as of 1:15 pm November 11th – Tom Petty Top Line Biden declared by multiple news networks to be America’s next president. Biden’s Pennsylvania win puts him over 270. Georgia and North Carolina not yet called. Biden narrowly leads in GA while Trump leads in NC. Trump campaign seeks recounts in GA and Wisconsin and files multiple lawsuits seeking to overturn the election results in states where Biden has won. Two January 5, 2021 runoff elections in Georgia will determine Senate control. Senator Mitch McConnell will remain Majority Leader and divided government will continue, complicating the prospects for Biden’s legislative agenda, unless Democrats win both runoff s. Democrats retain their House majority but Republicans narrow the Democrats’ margin with a net pickup of six seats. Incumbents Losing Reelection • Sen. Doug Jones (D-AL) • Rep. Harley Rouda (D-CA-48) • Rep. Xochitl Torres Small (D-NM-3) • Sen. Martha McSally (R-AZ) • Rep. Debbie Mucarsel-Powell (D-FL-26) • Rep. Max Rose (D-NY-11) • Sen. Cory Gardner (R-CO) • Rep. Donna Shalala (D-FL-27) • Rep. Kendra Horn (D-OK-5) • Rep. -

Sunday Morning Grid 9/28/14 Latimes.Com/Tv Times

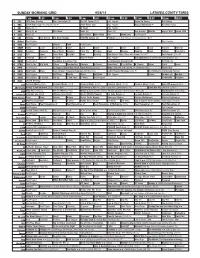

SUNDAY MORNING GRID 9/28/14 LATIMES.COM/TV TIMES 7 am 7:30 8 am 8:30 9 am 9:30 10 am 10:30 11 am 11:30 12 pm 12:30 2 CBS CBS News Sunday Face the Nation (N) The NFL Today (N) Å Paid Program Tunnel to Towers Bull Riding 4 NBC 2014 Ryder Cup Final Day. (4) (N) Å 2014 Ryder Cup Paid Program Access Hollywood Å Red Bull Series 5 CW News (N) Å In Touch Paid Program 7 ABC News (N) Å This Week News (N) News (N) Sea Rescue Wildlife Exped. Wild Exped. Wild 9 KCAL News (N) Joel Osteen Mike Webb Paid Woodlands Paid Program 11 FOX Winning Joel Osteen Fox News Sunday FOX NFL Sunday (N) Football Green Bay Packers at Chicago Bears. (N) Å 13 MyNet Paid Program Paid Program 18 KSCI Paid Program Church Faith Paid Program 22 KWHY Como Local Jesucristo Local Local Gebel Local Local Local Local Transfor. Transfor. 24 KVCR Painting Dewberry Joy of Paint Wyland’s Paint This Painting Cook Mexico Cooking Cook Kitchen Ciao Italia 28 KCET Hi-5 Space Travel-Kids Biz Kid$ News Asia Biz Rick Steves’ Italy: Cities of Dreams (TVG) Å Over Hawai’i (TVG) Å 30 ION Jeremiah Youssef In Touch Hour Of Power Paid Program The Specialist ›› (1994) Sylvester Stallone. (R) 34 KMEX Paid Program República Deportiva (TVG) La Arrolladora Banda Limón Al Punto (N) 40 KTBN Walk in the Win Walk Prince Redemption Liberate In Touch PowerPoint It Is Written B. Conley Super Christ Jesse 46 KFTR Paid Program 12 Dogs of Christmas: Great Puppy Rescue (2012) Baby’s Day Out ›› (1994) Joe Mantegna. -

David Skidmore CV 2020

DAVID G. SKIDMORE II Department of Political Science Drake University Des Moines, IA 50311 Phone: (515) 271-3843 FAX: (515) 271-1870 E-mail: [email protected] Blog: https://skidmore.blog/ Papers: https://drake.academia.edu/DavidSkidmore Google Scholar: https://scholar.google.com/citations?user=2LC1d3QAAAAJ&hl=en Amazon: https://www.amazon.com/author/dskidmore YouTube: https://www.youtube.com/channel/UChW192LAFMhx2jVALIx_a1w?view_as=subscriber EMPLOYMENT Professor, Drake University, 8/01-present. Visiting Professor, University of International Business and Economics, Beijing, China, 7/17. Visiting Fulbright Scholar, University of Hong Kong, 9/10-6/11. Associate Professor, Drake University, 8/94-8/01. Visiting Associate Professor, Johns Hopkins-Nanjing University Center for Chinese and American Studies, Nanjing, China, 9/96-6/97 Visiting Associate Professor, Rollins College, 1/3/96-1/31/96 Assistant Professor, Drake University, 8/89-7/94 Instructor, University of Notre Dame, 8/88-6/89 Instructor, Hamilton College, 6/86-6/88 EDUCATION Stanford University, Stanford, CA., M.A. (1981), Ph.D. (1989) degrees in Political Science. Rollins College, Winter Park, FL., B.A. (1979) degree in Political Science (Summa Cum Laude, Outstanding Senior Scholar, Political Science Student of the Year, Key Society). TEACHING EXPERIENCE World Politics American Foreign Policy International Political Economy International Relations Theory Latin American Politics Revisiting the Vietnam War Grassroots Globalism The Political Economy of Globalization