Between “Easter Island” and “Rapa Nui” 217 BETWEEN “EASTER ISLAND” and “RAPA NUI”

Total Page:16

File Type:pdf, Size:1020Kb

Load more

Recommended publications

-

Human Discovery and Settlement of the Remote Easter Island (SE Pacific)

quaternary Review Human Discovery and Settlement of the Remote Easter Island (SE Pacific) Valentí Rull Laboratory of Paleoecology, Institute of Earth Sciences Jaume Almera (ICTJA-CSIC), C. Solé i Sabarís s/n, 08028 Barcelona, Spain; [email protected] Received: 19 March 2019; Accepted: 27 March 2019; Published: 2 April 2019 Abstract: The discovery and settlement of the tiny and remote Easter Island (Rapa Nui) has been a classical controversy for decades. Present-day aboriginal people and their culture are undoubtedly of Polynesian origin, but it has been debated whether Native Americans discovered the island before the Polynesian settlement. Until recently, the paradigm was that Easter Island was discovered and settled just once by Polynesians in their millennial-scale eastward migration across the Pacific. However, the evidence for cultivation and consumption of an American plant—the sweet potato (Ipomoea batatas)—on the island before the European contact (1722 CE), even prior to the Europe-America contact (1492 CE), revived controversy. This paper reviews the classical archaeological, ethnological and paleoecological literature on the subject and summarizes the information into four main hypotheses to explain the sweet potato enigma: the long-distance dispersal hypothesis, the back-and-forth hypothesis, the Heyerdahl hypothesis, and the newcomers hypothesis. These hypotheses are evaluated in light of the more recent evidence (last decade), including molecular DNA phylogeny and phylogeography of humans and associated plants and animals, physical anthropology (craniometry and dietary analysis), and new paleoecological findings. It is concluded that, with the available evidence, none of the former hypotheses may be rejected and, therefore, all possibilities remain open. -

Chile and Argentina Easter Island Ext Feb2022 Updatedjun2020

E CHE SEM A N CHEESEMANS’ ECOLOGY SAFARIS E S C 2059 Camden Ave. #419 ’ O San Jose, CA 95124 USA L (800) 527-5330 (408) 741-5330 O G [email protected] Y S cheesemans.com A FA RIS Easter Island Extension Mysterious Moai February 23 to 28, 2022 Moai © Far South Expeditions EXTENSION OVERVIEW Join us on an exciting extension where you’ll stroll amongst the monolithic moai statues of Easter Island, carved from basalt lava by Polynesian settlers centuries ago. Visit abandoned settlements, explore ceremonial centers, and take a boat ride for a different perspective of the island, where you might see petroglyphs painted high on the cliffs above. Come along for an unforgettable journey of exploration into the history of Easter Island (Rapa Nui). HIGHLIGHTS • Learn about Easter Island’s moai statues and the tangata manu competition where rulership of Easter Island was defined through a ritual race for a bird egg. TRIP OPTION: This is a post-trip extension to our Chile and Argentina trip from February 11 to 24, 2022 (http://cheesemans.com/trips/chile-argentina-feb2022). Cheesemans’ Ecology Safaris Page 1 of 6 Updated: June 2020 LEADER: Josefina ‘Josie’ Nahoe Mulloy. DAYS: Adds 3 days to the main trip to total 17 days, including estimated travel time. GROUP SIZE: 8 (minimum of 4 required). COST: $2,230 per person, double occupancy, not including airfare, singles extra. See the Costs section on page 4. Date Description Accommodation Meals Feb 23 Fly from Punta Arenas to Santiago from our Chile Santiago Airport D and Argentina trip. -

EASTER ISLAND to TAHITI: TALES of the PACIFIC 2022 Route: Papeete, Tahiti, French Polynesia to Easter Island, Chile

EASTER ISLAND TO TAHITI: TALES OF THE PACIFIC 2022 route: Papeete, Tahiti, French Polynesia to Easter Island, Chile 19 Days National Geographic Resolution - 126 Guests National Geographic Orion - 102 Guests Expeditions in: Mar From $20,000 to $43,590 * Following in the wake of early Polynesian navigators, this voyage takes you to the farthest reaches of Oceania. From remote and enigmatic Easter Island, to the historically significant Pitcairn Islands through the “low islands” of the Tuamotu Archipelago to Tahiti, you’ll visit islands that are virtually inaccessible and untouched. The voyage begins in one of the most isolated landfalls of Polynesia: Easter Island. Walk the length of untouched tropical beaches, meet the descendants of H.M.S. Bounty mutineers, and drift dive or snorkel through an atoll pass. Call us at 1.800.397.3348 or call your Travel Agent. In Australia, call 1300.361.012 • www.expeditions.com DAY 1: U.S./Papeete, French Polynesia padding Depart in the late afternoon for Tahiti and arrive late in the evening on the same day. Check into a hotel room and spend the evening at your leisure. 2022 Departure Dates: 8 Nov DAY 2: Papeete/Embark padding This morning enjoy breakfast at your leisure and 2023 Departure Dates: spend some time exploring the resort while 6 Apr, 17 Apr adjusting to island time. Meet your fellow travelers for lunch and then join us for a tour of Tahiti before Important Flight Information embarking the ship in the late afternoon. (B,L,D) Please confirm arrival and departure dates prior to booking flights. -

The Pitcairn Islands the World’S Largest Fully Protected Marine Reserve

A fact sheet from March 2015 The Pitcairn Islands The world’s largest fully protected marine reserve Overview In March 2015, the United Kingdom declared the world’s largest fully protected marine reserve in the remote waters surrounding the Pitcairn Islands in the South Pacific Ocean. The designation marks the first time any government has combined creation of a fully protected marine area with detailed plans for surveillance and enforcement that include use of the most up-to-date technology available. This approach sets a new standard for the comprehensive monitoring of protected areas. In 2013, The Pew Charitable Trusts and The National Geographic Society joined the local government, the Pitcairn Island Council, in submitting a proposal calling for creation of a marine reserve to protect these spectacular waters. The Pitcairn Islands Marine Reserve spans 834,334 square kilometres (322,138 square miles). Together with the Chagos Marine Reserve in the Indian Ocean, designated in 2010, the United Kingdom has created the world’s two biggest fully protected marine areas, totalling 1,474,334 square kilometres (569,243 square miles). Through these actions, the United Kingdom—caretaker of the fifth-greatest amount of marine habitat of any country in the world—has established its place as a global leader in ocean conservation. Pitcairn Islands Marine Reserve Traditional and cultural non-commercial fishing by the Pitcairn islanders and their visitors is permitted within 2 nautical miles of the summit of 40 Mile Reef and in a transit zone between Pitcairn and 40 Mile Reef. © 2015 The Pew Charitable Trusts Encompassing 99 per cent of Pitcairn’s exclusive economic zone, the Pitcairn Islands Marine Reserve is about 3½ times the size of the land area of the United Kingdom. -

8124 Cuaderno Historia 36 Interior.Indd

View metadata, citation and similar papers at core.ac.uk brought to you by CORE provided by Revistas Académicas de la Universidad de Chile CUADERNOS DE HISTORIA 36 DEPARTAMENTO DE CIENCIAS HISTÓRICAS UNIVERSIDAD DE CHILE JUNIO 2012: 67 - 84 BAUTISTA COUSIN, SU MUERTE VIOLENTA Y LOS PRINCIPIOS DE AUTORIDAD EN RAPA NUI. 1914-1930* Rolf Foerster G.** The older people we found always kind and amiable, but the younger men have a high opinion of their own merits, and are often diffi cult to deal with1. RESUMEN: La muerte violenta de uno de los empleados de la Compañía Explotadora de Isla de Pascua, en agosto de 1915, permite arrojar luz sobre la comunidad rapanui, sus actos de rebelión y resistencia frente al poder colonial. Su efecto de “justicia”, junto a la rebelión “milenarista” de 1914, permitió que tanto el Estado (a través de la mediación del obispo castrense Edwards) como la Compañía modifi caran sus nexos coloniales con los rapanui (de “autoritarios” y “expoliadores” se pasa a unos “paternalistas” y “caritativos”, dando pie a formas híbridas de poder y de un cierto pluralismo legal). * Este artículo fue elaborado en el marco del proyecto FONDECYT Nº1110109. ** Doctor en Antropología, Universidad de Leiden (Holanda). Profesor Asociado Departamento de Antropología, Universidad de Chile. Correo electrónico: [email protected]. 1 Routledge, Catherine, The Mystery of Easter Island, Sifton, London, Praed & Co. Ltd., 1919, p. 140. 88124124 CCuadernouaderno hhistoriaistoria 3366 IInterior.inddnterior.indd 6677 224-07-20124-07-2012 111:14:051:14:05 CUADERNOS DE HISTORIA 36 / 2012 Estudios PALABRAS CLAVE: Isla de Pascua, Rapa Nui, Compañía Explotadora de Isla de Pascua, colonialismo, anti-colonialismo. -

THE HUMAN RIGHTS of the RAPA NUI PEOPLE on EASTER ISLAND Rapa Nui

THE HUMAN RIGHTS OF THE RAPA NUI PEOPLE ON EASTER ISLAND Rapa Nui IWGIA report 15 THE HUMAN RIGHTS OF THE RAPA NUI PEOPLE ON EASTER ISLAND Report of the international Observers’ Mission to Rapa Nui 2011 OBSERVERS: Clem Chartier, President of Métis National Council, Canada. Alberto Chirif, Anthropologist and Researcher, IWGIA, Peru. Nin Tomas, Associate Professor of Law at the University of Auckland in Aotearoa- New Zealand, and researcher in the area of Indigenous Peoples Rights. Rapa Nui: August 1 - 3, 2011 Santiago: August 4 - 8, 2011 Report 15 IWGIA - 2012 CONTENTS THE HUMAN RIGHTS OF THE RAPA NUI PEOPLE ON EASTER ISLAND Observer´s Report visit to Rapa Nui 2011 ISBN: 978-87-92786-27-2 PRESENTATION 5 Editor Observatorio Ciudadano 1. Historical information about the relationship between the Rapa Nui Design and layout people and the Chilean State 7 Lola de la Maza Cover photo 2. Diagnosis of the Human Rights situation of the Rapa Nui and their Isabel Burr, archivo Sacrofilm demands, with special reference to the rights of self-determination Impresión Impresos AlfaBeta and territorial rights 11 Santiago , Chile 2.1. Self Determination 12 2.1.1 Right to Consultation over Migration Control 18 2.1.2 Conclusion 20 2.2. Territorial Rights 21 OBSERVATORIO CIUDADANO Antonio Varas 428 - Temuco, Chile 2.2.1. Lands Occupations 21 Tel: 56 (45) 213963 - Fax 56 (45) 218353 E-mail: [email protected] - Web: www.observatorio.cl 2.2.2. Return of Lands 26 INTERNATIONAL WORK GROUP FOR INDIGENOUS AFFAIRS 3. RightS OF IndigEnouS PEoplES in ChilE 30 Classensgade 11 E, DK 2100 - Copenhagen, Denmark Tel: (45) 35 27 05 00 - Fax (45) 35 27 05 07 4. -

The Pitcairn Islands Marine Reserve (PDF)

A fact sheet from March 2015 The Pitcairn Islands Marine Reserve A global benchmark in marine protection Overview In September 2016, the United Kingdom created a fully protected marine reserve spanning about 830,000 square kilometres (320,465 square miles) in the remote waters surrounding the Pitcairn Islands in the South Pacific Ocean. The designation marked the first time that any government combined creation of a large, isolated and fully protected marine area with detailed plans for surveillance and enforcement that included use of the most up-to-date technology. This approach set a new standard for the comprehensive monitoring of protected areas. Three years earlier, in 2013, The Pew Trusts and the National Geographic Society had joined the local government, the Pitcairn Island Council, in submitting a proposal calling for creation of a marine reserve to safeguard these waters that teem with life. Together with the Chagos Marine Reserve in the Indian Ocean, designated in 2010, the United Kingdom has created two of the largest fully protected marine areas, totalling 1,470,000 square kilometres (567,017 square miles). Through these actions, the British government—caretaker of the fifth-greatest amount of marine habitat of any country in the world—has established its place as a global leader in ocean conservation. Pitcairn Islands Marine Reserve Traditional and cultural non-commercial fishing by the Pitcairn islanders and their visitors is permitted within 2 nautical miles of the summit of 40 Mile Reef and in a transit zone between Pitcairn and 40 Mile Reef. © 2017 The Pew Trusts Encompassing 99 per cent of Pitcairn’s exclusive economic zone, the Pitcairn Islands Marine Reserve is about 3½ times the size of the land area of the United Kingdom. -

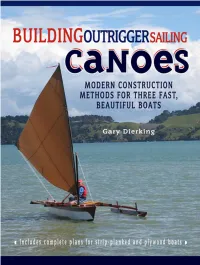

Building Outrigger Sailing Canoes

bUILDINGOUTRIGGERSAILING CANOES INTERNATIONAL MARINE / McGRAW-HILL Camden, Maine ✦ New York ✦ Chicago ✦ San Francisco ✦ Lisbon ✦ London ✦ Madrid Mexico City ✦ Milan ✦ New Delhi ✦ San Juan ✦ Seoul ✦ Singapore ✦ Sydney ✦ Toronto BUILDINGOUTRIGGERSAILING CANOES Modern Construction Methods for Three Fast, Beautiful Boats Gary Dierking Copyright © 2008 by International Marine All rights reserved. Manufactured in the United States of America. Except as permitted under the United States Copyright Act of 1976, no part of this publication may be reproduced or distributed in any form or by any means, or stored in a database or retrieval system, without the prior written permission of the publisher. 0-07-159456-6 The material in this eBook also appears in the print version of this title: 0-07-148791-3. All trademarks are trademarks of their respective owners. Rather than put a trademark symbol after every occurrence of a trademarked name, we use names in an editorial fashion only, and to the benefit of the trademark owner, with no intention of infringement of the trademark. Where such designations appear in this book, they have been printed with initial caps. McGraw-Hill eBooks are available at special quantity discounts to use as premiums and sales promotions, or for use in corporate training programs. For more information, please contact George Hoare, Special Sales, at [email protected] or (212) 904-4069. TERMS OF USE This is a copyrighted work and The McGraw-Hill Companies, Inc. (“McGraw-Hill”) and its licensors reserve all rights in and to the work. Use of this work is subject to these terms. Except as permitted under the Copyright Act of 1976 and the right to store and retrieve one copy of the work, you may not decompile, disassemble, reverse engineer, reproduce, modify, create derivative works based upon, transmit, distribute, disseminate, sell, publish or sublicense the work or any part of it without McGraw-Hill’s prior consent. -

Early Settlement Ofrapa Nui (Easter Island)

Early Settlement ofRapa Nui (Easter Island) HELENE MARTINSSON-WALLIN AND SUSAN J. CROCKFORD RAPA NUl, THE SMALL REMOTE ISLAND that constitutes the easternmost corner of the Polynesian triangle, was found and populated long before the Europeans "discovered" this part ofthe world in 1722. The long-standing questions concern ing this remarkable island are: who were the first to populate the island, at what time was it populated, and did the Rapa Nui population and development on the island result from a single voyage? Over the years there has been much discussion, speculation, and new scientific results concerning these questions. This has resulted in several conferences and numerous scientific and popular papers and monographs. The aim ofthis paper is to present the contemporary views on these issues, drawn from the results of the last 45 years of archaeological research on the island (Fig. 1), and to describe recent fieldwork that Martinsson-Wallin completed on Rapa Nui. Results from the Norwegian Archaeological Expedition to Rapa Nui in 1955 1956 suggest that the island was populated as early as c. A.D. 400 (Heyerdahl and Ferdon 1961: 395). This conclusion was drawn from a single radiocarbon date. This dated carbon sample (K-502) was found in association with the so-called Poike ditch on the east side of the island. The sample derived from a carbon con centration on the natural surface, which had been covered by soil when the ditch was dug. The investigator writes the following: There is no evidence to indicate that the fire from which the carbon was derived actually burned at the spot where the charcoal occurred, but it is clear that it was on the surface of the ground at the time the first loads of earth were carried out of the ditch and deposited over it. -

Qt7bj1m2m5.Pdf

UC Berkeley Berkeley Undergraduate Journal Title Between "Easter Island" and "Rapa Nui": The Making and Unmaking of an Uncanny Lifeworld Permalink https://escholarship.org/uc/item/7bj1m2m5 Journal Berkeley Undergraduate Journal, 27(2) ISSN 1099-5331 Author Seward, Pablo Howard Publication Date 2014 DOI 10.5070/B3272024077 Supplemental Material https://escholarship.org/uc/item/7bj1m2m5#supplemental Peer reviewed|Undergraduate eScholarship.org Powered by the California Digital Library University of California Between “Easter Island” and “Rapa Nui” 217 BETWEEN “EASTER ISLAND” AND “RAPA NUI” The Making and the Unmaking of an Uncanny Lifeworld By Pablo Seward his thesis is a historically informed ethnography of the Rapanui people of Easter Island. The restoration of this dispossessed and ravaged island by outsiders into what some scholars call “Museum Island” is the historical background on which the thesis is set. I argue that this Tpostcolonial process has produced in the Rapanui an uncanny affect when re-encountering their landscape and the emplaced persons within. I discuss the ontological, historical, and contemporary aspects of the case on the basis of ethnographic data I collected and archival research I conducted in Easter Island in the summer of 2013 and January 2014. In the first part, I use a semiotic approach to analyze how various Rapanui performance genres reveal Easter Island to be a landscape alive with emplaced other-than-human persons. In the second part, I examine the mediatization and politi- cal use of a leprosy epidemic from the 1890s to the 1960s in the island by the Chilean nation-state, focusing on how a new apparatus of power made autonomous citizens of Rapanui dividual persons. -

1 Cultural Identity and Heritage Prepared By: Ricardo Serpell, September 2018

EPFL | ENAC | IA Laboratory of construction and architecture Rapa Nui Superstudio 1 Cultural Identity and Heritage Prepared by: Ricardo Serpell, September 2018. A combination of geographic, historic and social factors allowed Chilean society to avoid the multiculturalist debate until very recently. Significant geographic isolation, high concentration of population on a few urban centres, and a steep socio-economic class system dominated by an upper group of strong European ascent favoured a hegemonic homogeneous-nation self-representation in the Chilean state construct. Indigenous population was historically overlooked amidst a dominant narrative of quasi-European white-mestizo nation with no “Indian problem”; an “exception” among “indigenous” and “backward” neighbour South American countries [1]. In such a context, for the Rapanui being granted Chilean citizenship in 1966 meant gaining long-denied fundamental rights, but at the same time adding to their struggle for recognition. 1.1 Worldviews Rapanui worldview has been constantly evolving after first European contact. Unable for most of its history to purposely reach out to other nations, understanding of themselves and the others in the world was challenged and then shaped by successive waves of external contact and intervention. The Rapanui worldview was suddenly required to incorporate the foreign and their everyday concerns forcibly displaced towards the sphere of external contact. Already in 1882, visitors were surprised to find that the Islanders knew accurately currency exchange rates and displayed their curios for sale with price tags on shelves [2]. Collective experience and memory of historical contact made the Rapanui simultaneously attracted and suspicious of the foreign. In many cases, the indigenous population has been divided in their perception and attitude towards incoming outsiders. -

Compañía, Estado Y Comunidad Isleña. Entre El “Pacto Colonial” Y La Resistencia

Compañía, Estado y Comunidad isleña. Entre el “pacto colonial” y la resistencia. Antecedentes y nuevas informaciones con respecto al periodo 1 1917-1936 Miguel Fuentes2 Resumen Teniendo por base la revisión de documentos provenientes del Archivo del Ministerio de Marina y del Archivo de la Intendencia de Valparaíso, este artículo se propone aportar con una caracterización inicial de la situación social y política en Rapa Nui durante el periodo 1917-1936. La elección de este periodo se justifica por la constatación que hacen varios investigadores acerca de la carencia de estudios que ayuden a comprender, para estos momentos, la dinámica social entre habitantes rapanui y agentes foráneos. Así también, pensamos que una serie de fenómenos marcan la apertura en 1917 de un nuevo escenario político. En este sentido, tanto la fallida rebelión isleña de 1914, así como el conflicto público entre el Obispo Edwards con la Compañía Explotadora en 1916 y la posterior firma del “Temperamento Provisorio”, provocaron una sustancial modificación del marco en el cual venían actuando los tres sujetos protagónicos del proceso histórico en Pascua: el Estado, la Compañía y la Comunidad isleña. Introducción Durante las últimas décadas del siglo XIX, el modo de vida tradicional rapanui experimenta importantes transformaciones que traen por consecuencia el surgimiento de un nuevo marco de relaciones sociales y políticas. En este contexto, una serie de sucesos marcan el desarrollo de un escenario en el cual se daría la acción (e interrelación) de tres sujetos claves: el Estado chileno, la “Compañía Explotadora de Isla de Pascua”3 y, aunque por mucho tiempo invisibilizada por el discurso histórico oficial, la Comunidad isleña4.