The Socio-Linguistic Paradox of Goa

Total Page:16

File Type:pdf, Size:1020Kb

Load more

Recommended publications

-

Newspaper Wise.Xlsx

PRINT MEDIA COMMITMENT REPORT FOR DISPLAY ADVT. DURING 2013-2014 CODE NEWSPAPER NAME LANGUAGE PERIODICITY COMMITMENT(%)COMMITMENTCITY STATE 310672 ARTHIK LIPI BENGALI DAILY(M) 209143 0.005310639 PORT BLAIR ANDAMAN AND NICOBAR 100771 THE ANDAMAN EXPRESS ENGLISH DAILY(M) 775695 0.019696744 PORT BLAIR ANDAMAN AND NICOBAR 101067 THE ECHO OF INDIA ENGLISH DAILY(M) 1618569 0.041099322 PORT BLAIR ANDAMAN AND NICOBAR 100820 DECCAN CHRONICLE ENGLISH DAILY(M) 482558 0.012253297 ANANTHAPUR ANDHRA PRADESH 410198 ANDHRA BHOOMI TELUGU DAILY(M) 534260 0.013566134 ANANTHAPUR ANDHRA PRADESH 410202 ANDHRA JYOTHI TELUGU DAILY(M) 776771 0.019724066 ANANTHAPUR ANDHRA PRADESH 410345 ANDHRA PRABHA TELUGU DAILY(M) 201424 0.005114635 ANANTHAPUR ANDHRA PRADESH 410522 RAYALASEEMA SAMAYAM TELUGU DAILY(M) 6550 0.00016632 ANANTHAPUR ANDHRA PRADESH 410370 SAKSHI TELUGU DAILY(M) 1417145 0.035984687 ANANTHAPUR ANDHRA PRADESH 410171 TEL.J.D.PATRIKA VAARTHA TELUGU DAILY(M) 546688 0.01388171 ANANTHAPUR ANDHRA PRADESH 410400 TELUGU WAARAM TELUGU DAILY(M) 154046 0.003911595 ANANTHAPUR ANDHRA PRADESH 410495 VINIYOGA DHARSINI TELUGU MONTHLY 18771 0.00047664 ANANTHAPUR ANDHRA PRADESH 410398 ANDHRA DAIRY TELUGU DAILY(E) 69244 0.00175827 ELURU ANDHRA PRADESH 410449 NETAJI TELUGU DAILY(E) 153965 0.003909538 ELURU ANDHRA PRADESH 410012 ELURU TIMES TELUGU DAILY(M) 65899 0.001673333 ELURU ANDHRA PRADESH 410117 GOPI KRISHNA TELUGU DAILY(M) 172484 0.00437978 ELURU ANDHRA PRADESH 410009 RATNA GARBHA TELUGU DAILY(M) 67128 0.00170454 ELURU ANDHRA PRADESH 410114 STATE TIMES TELUGU DAILY(M) -

Wholesale List at Bardez

BARDEZ Sr.No Name & Address of The Firm Lic. No. Issued Dt. Validity Dt. Old Lic No. 1 M/s. Rohit Enterprises, 5649/F20B 01/05/1988 31/12/2021 913/F20B 23, St. Anthony Apts, Mapuca, Bardez- Goa 5651/F21B 914/F21B 5650/20D 24/20D 2 M/s. Shashikant Distributors., 6163F20B 13/04/2005 18/11/2019 651/F20B Ganesh Colony, HNo.116/2, Near Village 6164/F20D 652/F21B Panchyat Punola, Ucassim , Bardez – Goa. 6165/21B 122/20D 3 M/s. Raikar Distributors, 5022/F20B 27/11/2014 26/11/2019 Shop No. E-4, Feira Alto, Saldanha Business 5023/F21B Towers, Mapuca – Goa. 4 M/s. Drogaria Ananta, 7086/F20B 01/04/2008 31/03/2023 449/F20B Joshi Bldg, Shop No.1, Mapuca, Bardez- Goa. 7087/F21B 450/F21B 5 M/s. Union Chemist& Druggist, 5603/F20B 25/08/2011 24/08/2021 4542/F20B Wholesale (Godown), H No. 222/2, Feira Alto, 5605/F21B 4543/F21B Mapuca Bardez – Goa. 5604/F20D 6 M/s. Drogaria Colvalcar, 5925/F20D 09/11/2017 09/11/2019 156/F20B New Drug House, Devki Krishna Nagar, Opp. 6481/F20 B 157/F21B Fomento Agriculture, Mapuca, Bardez – Goa. 6482/F21B 121/F20D 5067/F20G 08/11/2022 5067/20G 7 M/s. Sharada Scientific House, 5730/F20B 07/11/1990 31/12/2021 1358/F20B Bhavani Apts, Dattawadi Road, Mapuca Goa. 5731/F21B 1359/F21B 8 M/s. Valentino F. Pinto, 6893/F20B 01/03/2013 28/02/2023 716/F20B H. No. 5/77A, Altinho Mapuca –Goa. 6894/F21B 717/F21B 9 M/s. -

Environmental Public Hearing Welcome To

WELCOME TO ENVIRONMENTAL PUBLIC HEARING FOR UP-GRADATION OF BLAST FURNACES (BF) TO ENHANCE THE PRODUCTION CAPACITY OF • BF-1 & 2 FROM 2,92,000 TPA TO 3,50,000 TPA, • BF-3 FROM 5,40,000 TPA TO 6,50,000 TPA, • SETTING UP OF ADDITIONAL OXYGEN PLANT, • INSTALLATION OF DUCTILE IRON PIPE PLANT OF 3,00,000 TPA CAPACITY, • 4 ADDITIONAL MET COKE OVENS, • SETTING UP OF FE-SI PLANT OF 5,000 TPA CAPACITY AT AMONA AND NAVELIM VILLAGES, BICHOLIM TALUKA, NORTH GOA DISTRICT, GOA Project Proponent Environment Consultant M/s. Vedanta Limited Vimta Labs Ltd., Hyderabad Goa (QCI/NABET Accredited EIA Consultancy Organization, QCI Sr. No. 163, NABL Accredited & ISO 17025 Certified and MoEF&CC Recognized Laboratory) 1 PROJECT PROPONENT • Vedanta Limited, formerly Sesa Goa Limited, is the subsidiary of Vedanta Ltd. • The company’s main business focus on zinc, lead, silver, aluminum, copper, iron ore, oil & gas and commercial power, while its operations span across India, South Africa, Namibia, the Republic of Ireland, Australia and Liberia. • Sesa Goa has been engaged in exploration, mining and processing of iron ore. • The group has been involved in iron ore mining, beneficiation and exports. • During 1991-1995, it diversified into the manufacture of pig iron and metallurgical coke. • Vedanta operates value addition business in Goa with 832 KTPA hot metal, 1 MTPA sinter, 622 KTPA coke plant and 65 MW waste heat recovery power plant. 2 PROJECT PROPOSAL • TOR application for integrated proposal was filed vide proposal no. IA/GA/IND/89225/2018 dated 20th December, 2018. Based on the TOR conditions stipulated by MoEF&CC vide letter No. -

Official Gazette Government Of" Goa~ 'Daman and Diu;

, , 'J REGD. GOA-IS r Panaji, 30th March, 1982 ('Chaitra 9,1904! SERIES II No. 52 OFFICIAL GAZETTE GOVERNMENT OF" GOA~ 'DAMAN AND DIU; EXTftl\O ft[) IN 1\ ftV GOVERNMENT OF GQA, DAMAN, AND DIU Works, Education and Tourism Department Irrigatio';" Department Notification No. CE/lrrigation/431/81 Whereas it appears expedient to the Government ,that the water of the rivers and its main tributal'ies ~dj}~-trt butaries as specified in column 2 of the Schedule annexed hereto (hereafter called as the said water) be applied ,:r and used- by the Government for the' purpose of the proposed canals, as specified in column 2 within the limits specified in the corresponding entrieo$ in columns 3 to,,6 _of :the said,,-S~hed1:l1e. NOW, .thefe:fore~ 'in' exercise of. powers 'confer~ed' by 'Section 4 of the. Goa. Daman and Diu Irrigation Act, 1973 (18 of 1973) the Adm.:ll'listrator of Goa, Daman' and Diu -,hereby declares that" the said water will be so -appUed and used after 1·7·1982. ". :', '< > SCHEDULE t(:uoe of Village, Taiukas, Du,trict in which'the water Name of water source source is situated :sr. No. and naUahs etc. Description of source of wate!' Village. Taluka. District, 1 2 3 • 5 6 IN GOA DISTRICT 1. Tiracol River: For Minor Irrigatiot.. Work Tiracol river is on the boundary of Patradevi, Torxem, ~\, namely Bandhara at Kiran· Maharashtra State and Goa territory. Uguem, Porosco~ pan!' It originates from the Western Ghat dem, Naibag, Ka· Region of Maharashtra State and ribanda D e U 8, Pemem Goa ~nters in Goa Distrtct at Patradevi Paliem., Kiranpani, village including all .the tributaries, Querim and Tira streams and nal.1as flowing Westward col. -

Pray for India Pray for Rulers of Our Nation Praise God for The

Pray for India “I have posted watchmen on your walls, Jerusalem; they will never be silent day or night. You who call on the Lord, give yourselves no rest, and give him no rest till he establishes Jerusalem and makes her the praise of the earth” (Isaiah 62:6-7) Population : 127.08 crores Christians 6 crores approx. (More than 5% - assumed) States : 29 Union Territories : 7 Lok Sabha & Rajya Sabha Members : 780 MLA’s : 4,120 Approx. 30% of them have criminal backgrounds Villages : 7 lakh approx. (No Churches in 5 lakh villages) Towns : 31 (More than 10 lakh population) 400 approx. (More than 1 lakh population) People Groups : 4,692 Languages : 460 (Official languages - 22) Living in slums : 6,50,00,000 approx. Pray for Rulers of our Nation President of India : Mr. Ram Nath Kovind Prime Minister : Mr. Narendra Modi Lok Sabha Sepeaker : Mrs. Sumitra Mahajan Central Cabinet, Ministers of state, Deputy ministers, Opposition leaders and members to serve with uprightness. Governors of the states, Chief Ministers, Assembly leaders, Ministers, Members of Legislative Assembly, Leaders and Members of the Corporations, Municipalities and Panchayats to serve truthfully. General of Army, Admirals of Navy and Air Marshals of Air force. Planning Commission Chairman and Secretaries. Chief Secretaries, Secretaries, IAS, IPS, IFS Officials. District collectors, Tahsildars, Officials and Staff of the departments of Revenue, Education, Public works, Health, Commerce, Agriculture, Housing, Industry, Electricity, Judiciary, etc. Heads, Officials and Staff of Private sectors and Industries. The progress of farmers, businessmen, fisher folks, self-employed, weavers, construction workers, computer operators, sanitary workers, road workers, etc. -

Journal of Social and Economic Development

Journal of Social and Economic Development Vol. 4 No.2 July-December 2002 Spatial Poverty Traps in Rural India: An Exploratory Analysis of the Nature of the Causes Time and Cost Overruns of the Power Projects in Kerala Economic and Environmental Status of Drinking Water Provision in Rural India The Politics of Minority Languages: Some Reflections on the Maithili Language Movement Primary Education and Language in Goa: Colonial Legacy and Post-Colonial Conflicts Inequality and Relative Poverty Book Reviews INSTITUTE FOR SOCIAL AND ECONOMIC CHANGE BANGALORE JOURNAL OF SOCIAL AND ECONOMIC DEVELOPMENT (Published biannually in January and July) Institute for Social and Economic Change Bangalore–560 072, India Editor: M. Govinda Rao Managing Editor: G. K. Karanth Associate Editor: Anil Mascarenhas Editorial Advisory Board Isher Judge Ahluwalia (Delhi) J. B. Opschoor (The Hague) Abdul Aziz (Bangalore) Narendar Pani (Bangalore) P. R. Brahmananda (Bangalore) B. Surendra Rao (Mangalore) Simon R. Charsley (Glasgow) V. M. Rao (Bangalore) Dipankar Gupta (Delhi) U. Sankar (Chennai) G. Haragopal (Hyderabad) A. S. Seetharamu (Bangalore) Yujiro Hayami (Tokyo) Gita Sen (Bangalore) James Manor (Brighton) K. K. Subrahmanian Joan Mencher (New York) (Thiruvananthapuram) M. R. Narayana (Bangalore) A. Vaidyanathan (Thiruvananthapuram) DTP: B. Akila Aims and Scope The Journal provides a forum for in-depth analysis of problems of social, economic, political, institutional, cultural and environmental transformation taking place in the world today, particularly in developing countries. It welcomes articles with rigorous reasoning, supported by proper documentation. Articles, including field-based ones, are expected to have a theoretical and/or historical perspective. The Journal would particularly encourage inter-disciplinary articles that are accessible to a wider group of social scientists and policy makers, in addition to articles specific to particular social sciences. -

Tourism in the Global South

This book intends to discuss new research ideas on the tourism impacts in the Global South, focusing namely on the construction and transformation of landscapes through tourism, TOURISM IN THE GLOBAL SOUTH on issues of identity friction and cultural change, and on the HERITAGES, IDENTITIES AND DEVELOPMENT responsibility of tourism on poverty reduction and sustainable development. A proper analysis of tourism impacts always needs an interdisciplinary approach. Geography can conduct a stimulating job since it relates culture and nature, society and environment, space, economy and politics, but a single discipline cannot push our understanding very far without intersecting it with other realms of knowledge. So, this is a book that aims at a multidisciplinary debate, celebrating the diversity of disciplinary boundaries, and which includes texts from and people from a range of different backgrounds such as Geography, Tourism, Anthropology, Architecture, Cultural Edited by Studies, Linguistics and Economics. João Sarmento Eduardo Brito-Henriques TOURISM IN THE GLOBAL SOUTH IN THE GLOBAL TOURISM AND DEVELOPMENT IDENTITIES HERITAGES, TTOURISMOURISM GGLOBAL(9-1-2013).inddLOBAL(9-1-2013).indd 1 CMYK 117-01-20137-01-2013 112:40:162:40:16 10. SHOW-CASING THE PAST: ON AGENCY, SPACE AND TOURISM Ema Pires In this paper, I wish to contribute to an understanding of the linkages between tourism, space and power, in order to explore how these aspects relate to peoples’ spatial practices. Using a diachronic approach to tourism, this paper argues that in order to understand tourism phenomenon we cannot do without three intertwined categories: time, space and power. Indeed, understanding spaces of tourism is closely related with depicting their multiple layers of fabric weaved through the passing of time. -

Women´S Writing and Writings on Women In

WOMEN´S WRITING AND WRITINGS ON WOMEN IN THE GOAN MAGAZINE O ACADÉMICO (1940– 1943)1 A ESCRITA DE MULHERES E A ESCRITA SOBRE MULHERES NA REVISTA GOESA O ACADÉMICO (1940 – 1943) VIVIANE SOUZA MADEIRA2 ABSTRACT: This article discusses some texts, written by women, as well as texts on women, written by men, in the Goan magazineO Académico (1940-1943). Even though O Académico is not particularly aimed at women’s readership, but at a broader audience – the “Goan youth” – it contains articles that deal with the question of women in the spheres of science, politics and literature. As one of the magazine’s objectives was to “emancipate Goan youth intellectually”, we understand that young women’s education was also within their scope, focusing on the question of women’s roles. The Goan intelligentsia that made up the editorial board of the publication revealed their desire for modernization by showing their preoccupation with forward-looking ideas and by providing a space for women to publish their texts. KEYWORDS: Women’s writing, Men writing on women, Periodical Press,O Académico, Goa. RESUMO: Este artigo discute textos escritos sobre mulheres, por homens e por mulheres, na revista goesa O Académico (1940-1943). Embora não tenha sido particularmente voltada as leitoras, mas a um público mais amplo – a “juventude goesa” – a revista contém artigos que abordam a questão da mulher nas esferas da ciência, da política e da literatura. Como um dos seus objetivos era “emancipar intelectualmente a juventude goesa”, entendemos que a educação das jovens de Goa estava no escopo da publicação, focando também na questão dos papéis que essas mulheres cumpriam em sua sociedade. -

Annualrepeng II.Pdf

ANNUAL REPORT – 2007-2008 For about six decades the Directorate of Advertising and on key national sectors. Visual Publicity (DAVP) has been the primary multi-media advertising agency for the Govt. of India. It caters to the Important Activities communication needs of almost all Central ministries/ During the year, the important activities of DAVP departments and autonomous bodies and provides them included:- a single window cost effective service. It informs and educates the people, both rural and urban, about the (i) Announcement of New Advertisement Policy for nd Government’s policies and programmes and motivates print media effective from 2 October, 2007. them to participate in development activities, through the (ii) Designing and running a unique mobile train medium of advertising in press, electronic media, exhibition called ‘Azadi Express’, displaying 150 exhibitions and outdoor publicity tools. years of India’s history – from the first war of Independence in 1857 to present. DAVP reaches out to the people through different means of communication such as press advertisements, print (iii) Multi-media publicity campaign on Bharat Nirman. material, audio-visual programmes, outdoor publicity and (iv) A special table calendar to pay tribute to the exhibitions. Some of the major thrust areas of DAVP’s freedom fighters on the occasion of 150 years of advertising and publicity are national integration and India’s first war of Independence. communal harmony, rural development programmes, (v) Multimedia publicity campaign on Minority Rights health and family welfare, AIDS awareness, empowerment & special programme on Minority Development. of women, upliftment of girl child, consumer awareness, literacy, employment generation, income tax, defence, DAVP continued to digitalize its operations. -

Audit-Reg-Corp.Pdf

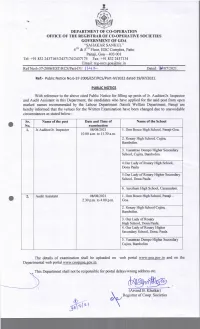

Venues for the post of Jr. Auditor/Jr. Inspector Date and Day: Sunday 08.08.2021 Time:10.00 a.m. to 11.30 a.m. Morning Session Sr. Name of the School Roll No. No. 1. Don Bosco High School, Panaji – Goa 1 to 500 2. Rosary High School, Cujira, Bambolim 501 to 940 3. Vasantrao Dempo Higher Secondary 941 to 1063 School, Cujira, Bambolim 4. Our Lady of Rosary High School, 1064 to 1339 Dona Paula 5. Our Lady of Rosary Higher Secondary 1340 to 1539 School, Dona Paula 6. Auxilium High School, Caranzalem 1540 to 1639 Venues for the post of Audit Assistant Date and Day: Sunday 08.08.2021 Time: 2.30 p.m. to 4.00 p.m. Evening Session Sr. Name of the School Roll No. No. 1. Don Bosco High School, Panaji – Goa 1 to 500 2. Rosary High School, Cujira, Bambolim 501 to 940 3. Our Lady of Rosary High School, 941 to 1240 Dona Paula 4. Our Lady of Rosary Higher Secondary 1241 to 1440 School, Dona Paula 5. Vasantrao Dempo Higher Secondary 1441 to 1546 School, Cujira, Bambolim 1 List of the Candidates for the post of Audit Assistant for examination to be held on 08/08/2021 at 2.30 p.m. to 4.00 p.m. In Don Bosco High School, Panaji-Goa from Roll No. 001 to 500 Roll No. Name & Address of the Candidate 001 Muriel Philip D’ Souza, H. No. 156, Angod, Mapusa, Bardez Goa. 002 Nivedita Sudhakar Achari, H. No. 271, khareband Road, Margao Goa 403601. -

If Goa Is Your Land, Which Are Your Stories? Narrating the Village, Narrating Home*

If Goa is your land, which are your stories? Narrating the Village, Narrating Home* Cielo Griselda Festinoa Abstract Goa, India, is a multicultural community with a broad archive of literary narratives in Konkani, Marathi, English and Portuguese. While Konkani in its Devanagari version, and not in the Roman script, has been Goa’s official language since 1987, there are many other narratives in Marathi, the neighbor state of Maharashtra, in Portuguese, legacy of the Portuguese presence in Goa since 1510 to 1961, and English, result of the British colonization of India until 1947. This situation already reveals that there is a relationship among these languages and cultures that at times is highly conflictive at a political, cultural and historical level. In turn, they are not separate units but are profoundly interrelated in the sense that histories told in one language are complemented or contested when narrated in the other languages of Goa. One way to relate them in a meaningful dialogue is through a common metaphor that, at one level, will help us expand our knowledge of the points in common and cultural and * This paper was carried out as part of literary differences among them all. In this article, the common the FAPESP thematic metaphor to better visualize the complex literary tradition from project "Pensando Goa" (proc. 2014/15657-8). The Goa will be that of the village since it is central to the social opinions, hypotheses structure not only of Goa but of India. Therefore, it is always and conclusions or recommendations present in the many Goan literary narratives in the different expressed herein are languages though from perspectives that both complement my sole responsibility and do not necessarily and contradict each other. -

Integration and Conflict in Indonesia's Spice Islands

Volume 15 | Issue 11 | Number 4 | Article ID 5045 | Jun 01, 2017 The Asia-Pacific Journal | Japan Focus Integration and Conflict in Indonesia’s Spice Islands David Adam Stott Tucked away in a remote corner of eastern violence, in 1999 Maluku was divided into two Indonesia, between the much larger islands of provinces – Maluku and North Maluku - but this New Guinea and Sulawesi, lies Maluku, a small paper refers to both provinces combined as archipelago that over the last millennia has ‘Maluku’ unless stated otherwise. been disproportionately influential in world history. Largely unknown outside of Indonesia Given the scale of violence in Indonesia after today, Maluku is the modern name for the Suharto’s fall in May 1998, the country’s Moluccas, the fabled Spice Islands that were continuing viability as a nation state was the only place where nutmeg and cloves grew questioned. During this period, the spectre of in the fifteenth century. Christopher Columbus Balkanization was raised regularly in both had set out to find the Moluccas but mistakenly academic circles and mainstream media as the happened upon a hitherto unknown continent country struggled to cope with economic between Europe and Asia, and Moluccan spices reverse, terrorism, separatist campaigns and later became the raison d’etre for the European communal conflict in the post-Suharto presence in the Indonesian archipelago. The transition. With Yugoslavia’s violent breakup Dutch East India Company Company (VOC; fresh in memory, and not long after the demise Verenigde Oost-indische Compagnie) was of the Soviet Union, Indonesia was portrayed as established to control the lucrative spice trade, the next patchwork state that would implode.