Imaging Royalty

Total Page:16

File Type:pdf, Size:1020Kb

Load more

Recommended publications

-

FACE to FACE Gallery News Issue No

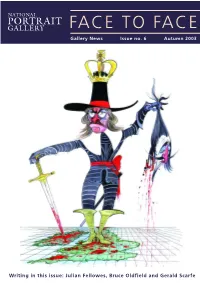

P FACE TO FACE Gallery News Issue no. 6 Autumn 2003 Writing in this issue: Julian Fellowes, Bruce Oldfield and Gerald Scarfe FROM THE DIRECTOR The autumn exhibition Below Stairs: 400 Years of Servants’ Portraits offers an unusual opportunity to see fascinating images of those who usually remain invisible. The exhibition offers intriguing stories of the particular individuals at the centre of great houses, colleges or business institutions and reveals the admiration and affection that caused the commissioning of a portrait or photograph. We are also celebrating the completion of the new scheme for Trafalgar Square with the young people’s education project and exhibition, Circling the Square, which features photographs that record the moments when the Square has acted as a touchstone in history – politicians, activists, philosophers and film stars have all been photographed in the Square. Photographic portraits also feature in the DJs display in the Bookshop Gallery, the Terry O’Neill display in the Balcony Gallery and the Schweppes Photographic Portrait Prize launched in November in the Porter Gallery. Gerald Scarfe’s rather particular view of the men and women selected for the Portrait Gallery is published at the end of September. Heroes & Villains, is a light hearted and occasionally outrageous view of those who have made history, from Elizabeth I and Oliver Cromwell to Delia Smith and George Best. The Gallery is very grateful for the support of all of its Patrons and Members – please do encourage others to become Members and enjoy an association with us, or consider becoming a Patron, giving significant extra help to the Gallery’s work and joining a special circle of supporters. -

Darnley Portraits

DARNLEY FINE ART DARNLEY FINE ART PresentingPresenting anan Exhibition of of Portraits for Sale Portraits for Sale EXHIBITING A SELECTION OF PORTRAITS FOR SALE DATING FROM THE MID 16TH TO EARLY 19TH CENTURY On view for sale at 18 Milner Street CHELSEA, London, SW3 2PU tel: +44 (0) 1932 976206 www.darnleyfineart.com 3 4 CONTENTS Artist Title English School, (Mid 16th C.) Captain John Hyfield English School (Late 16th C.) A Merchant English School, (Early 17th C.) A Melancholic Gentleman English School, (Early 17th C.) A Lady Wearing a Garland of Roses Continental School, (Early 17th C.) A Gentleman with a Crossbow Winder Flemish School, (Early 17th C.) A Boy in a Black Tunic Gilbert Jackson A Girl Cornelius Johnson A Gentleman in a Slashed Black Doublet English School, (Mid 17th C.) A Naval Officer Mary Beale A Gentleman Circle of Mary Beale, Late 17th C.) A Gentleman Continental School, (Early 19th C.) Self-Portrait Circle of Gerard van Honthorst, (Mid 17th C.) A Gentleman in Armour Circle of Pieter Harmensz Verelst, (Late 17th C.) A Young Man Hendrick van Somer St. Jerome Jacob Huysmans A Lady by a Fountain After Sir Peter Paul Rubens, (Late 17th C.) Thomas Howard, Earl of Arundel After Sir Peter Lely, (Late 17th C.) The Duke and Duchess of York After Hans Holbein the Younger, (Early 17th to Mid 18th C.) William Warham Follower of Sir Godfrey Kneller, (Early 18th C.) Head of a Gentleman English School, (Mid 18th C.) Self-Portrait Circle of Hycinthe Rigaud, (Early 18th C.) A Gentleman in a Fur Hat Arthur Pond A Gentleman in a Blue Coat -

Caricature: the Loaded Drawing

Caricature: The Loaded Drawing The taste of the day leans entirely to caricature. We have lost our relish for the simple beauties of nature. We are no longer satisfied with propriety and neatness, we must have something grotesque and disproportioned, cumbrous with ornament and gigantic in its dimensions Morning Chronicles 1 1, August, 1796 Exaggeration in visual expression is found in nearly all cultures and throughout most historical periods. What this paper will discuss is the use of caricature to communicate satirical/humorous content in visual genres of Western Europe and specifically 18th Century England by highlighting the work of James Gillray. Caricature of Libyan leader Caricature is a form of visual exaggeration/distortion Muammar Gaddafi held by that generally pertains to the human face and/or figure drawn protestors on 2. 27. 2011. Source: NY Times online for humorous, critical or vindictive motives. As the title suggests, a particular facial part is exaggerated to catch the viewers’ attention and relate that quality to underlying aspects of the personality – hence a caricature is a portrait that is loaded with meaning rather than mere description. The centuries old premise to this interpretation is that outward appearances belie personality traits. A second interpretation of caricature - and the one this paper focuses on - combines the transformative aspects of caricature rendering techniques with satire to produce graphic images that provoke meaning in political, social and moral arenas. A verbal cousin to visual caricature is satire. Satirizing the human condition is as universal as exaggeration, and while found in early Greco- Roman art and literature wanes through the medieval period. -

Italian Titles of Nobility

11/8/2020 Italian Titles of Nobility - A Concise, Accurate Guide to Nobiliary History, Tradition and Law in Italy until 1946 - Facts, no… Italian Titles of Nobility See also: Sicilian Heraldry & Nobility • Sicilian Genealogy • Books • Interview ©1997 – 2015 Louis Mendola Author's Note An article of this length can be little more than a precis. Apart from the presentation of the simplest facts, the author's intent is to provide accurate information, avoiding the bizarre ideas that color the study of the aristocracy. At best, this web page is a ready reference that offers a quick overview and a very concise bibliography; it is intended as nothing more. This page is published for the benefit of the historian, genealogist, heraldist, researcher or journalist – and all scientific freethinkers – in search of an objective, unbiased summary that does not seek (or presume) to insult their knowledge, intelligence or integrity. The study of the nobility and heraldry simply cannot exist without a sound basis in genealogical science. Genealogy is the only means of demonstrating familial lineage (ancestry), be it proven through documentation or DNA, be it aristocratic or humble. At 300 pages, the book Sicilian Genealogy and Heraldry considers the subject in far greater detail over several chapters, and while its chief focus is the Kingdom of Sicily, it takes into account the Kingdom of Italy (1861-1946) as well. That book includes chapters dedicated to, among other things, historiography, feudal law and proof standards. Like this web page, the book (you can peruse the table of contents, index and a few pages on Amazon's site) is the kind of reference and guide the author wishes were available when he began to study these fields seriously over thirty years ago. -

Annual Review 2011 – 2012

AnnuA l Review 2011 – 2012 Dulwich Picture Gallery was established more than 200 years ago because its founders believed as many people as possible should see great paintings. Today we believe the same, because we know that art can change lives. I w hat makes us world-class is our exceptional collection of Old Master paintings. I england – which allows visitors to experience those paintings in an intimate, welcoming setting. I w hat makes us relevant is the way we unite our past with our present, using innovative exhibitions, authoritative scholarship and pioneering education programmes to change lives for the better. Cover image: installation view of David Hockney, Mr and Mrs Clark and Percy, 1970-71, acrylic on canvas, 213 x 304. Tate, Presented by the Friends of the Tate Gallery 1971 © David Hockeny / Tate. Dulwich Picture Gallery is built on history. Picture Our From our founders’ wish to have an art Future: The Campaign for Dulwich Picture recognises a number of things of which gallery ‘for the inspection of the public’, Gallery has begun. Alongside my co-chair artists and scholars, aristocrats and school of the Campaign Cabinet, Bernard Hunter, particularly to celebrate our long-time children have come by horse, train, car we look forward to working with all of the Trustee and supporter Theresa Sackler, and bicycle to view our collection – Van Gallery’s supporters to reach this goal. who was recently awarded a DBE Gogh walked from Central London to view in the Queen’s Birthday Honours List, the Gallery in 1873. The paintings and The position we start from is a strong adding even more lustre to the Prince of building are a monument to the tastes of one: against the background of a troubled Wales’ Medal for Philanthropy which was two centuries ago, yet it is a testament world-economy, the Gallery exceeded its awarded to her in 2011. -

Journal of Irish and Scottish Studies Cultural Exchange: from Medieval

Journal of Irish and Scottish Studies Volume 1: Issue 1 Cultural Exchange: from Medieval to Modernity AHRC Centre for Irish and Scottish Studies JOURNAL OF IRISH AND SCOTTISH STUDIES Volume 1, Issue 1 Cultural Exchange: Medieval to Modern Published by the AHRC Centre for Irish and Scottish Studies at the University of Aberdeen in association with The universities of the The Irish-Scottish Academic Initiative and The Stout Research Centre Irish-Scottish Studies Programme Victoria University of Wellington ISSN 1753-2396 Journal of Irish and Scottish Studies Issue Editor: Cairns Craig Associate Editors: Stephen Dornan, Michael Gardiner, Rosalyn Trigger Editorial Advisory Board: Fran Brearton, Queen’s University, Belfast Eleanor Bell, University of Strathclyde Michael Brown, University of Aberdeen Ewen Cameron, University of Edinburgh Sean Connolly, Queen’s University, Belfast Patrick Crotty, University of Aberdeen David Dickson, Trinity College, Dublin T. M. Devine, University of Edinburgh David Dumville, University of Aberdeen Aaron Kelly, University of Edinburgh Edna Longley, Queen’s University, Belfast Peter Mackay, Queen’s University, Belfast Shane Alcobia-Murphy, University of Aberdeen Brad Patterson, Victoria University of Wellington Ian Campbell Ross, Trinity College, Dublin The Journal of Irish and Scottish Studies is a peer reviewed journal, published twice yearly in September and March, by the AHRC Centre for Irish and Scottish Studies at the University of Aberdeen. An electronic reviews section is available on the AHRC Centre’s website: http://www.abdn.ac.uk/riiss/ahrc- centre.shtml Editorial correspondence, including manuscripts for submission, should be addressed to The Editors,Journal of Irish and Scottish Studies, AHRC Centre for Irish and Scottish Studies, Humanity Manse, 19 College Bounds, University of Aberdeen, AB24 3UG or emailed to [email protected] Subscriptions and business correspondence should be address to The Administrator. -

Britain's Defeat in the American Revolution: Four British Cartoons, 1782

MAKING THE REVOLUTION: AMERICA, 1763-1791 PRIMARY SOURCE COLLECTION __BRITAIN’S DEFEAT IN THE AMERICAN REVOLUTION: FOUR BRITISH CARTOONS, 1782__ * The rattlesnake as a symbol of the American colonies originated with Benjamin Franklin’s Join or Die cartoon of 1754, which he printed above his newspaper essay urging unity among the colonies for defense against the French and Indians on the frontier. So in 1782, as Britain was reeling from defeat and maneuvering through treaty negotiations with the U.S. and its allies, English cartoonists relished portraying the U.S. as a vengeful and menacing rattlesnake. Europeans had long been fascinated by accounts of the rattlesnake’s threat and prowesswhich translated into “deceitful foe”and yet the cartoonists’ awe of the coiled muscular reptile is evident. The United States was a power to contend with, period, and the standard symbol of an Indian princess for America was no longer apt. Rarely printed in newspapers at the time, political cartoons were usually published by printmakers as large etchingsthe four in this selection average 9 x 13½ inches. They were called satires or caricatures; the term cartoon was not commonly applied to such illustrations until the mid 1800s. What impressions do the cartoonists give of the U.S. and Britain in these satires? How do they characterize the nations’ new The American Rattle Snake, London, 12 April 1782 relationship in 1782? How do they The British Lion engaging Four Powers, London, 14 June 1782 acknowledge that the U.S. is, in- deed, a nation among nations? The American Rattlesnake presenting Monsieur Franklin’s cartoon in his Philadelphia Paradice Lost [sic], London, 10 May 1782 his Ally a Dish of Frogs, London, 8 November 1782 Gazette, 9 May 1754 * ® Copyright © National Humanities Center, 2010/2013. -

Honour and the Art of Xenophontic Leadership *

Histos Supplement ( ) – HONOUR AND THE ART OF XENOPHONTIC LEADERSHIP * Benjamin D. Keim Abstract : Throughout his wide-ranging corpus Xenophon portrays the desire for honour as a fundamentally human characteristic, one commonly attributed to rulers and commanders and yet also found among other individuals, regardless of their sex or social status. Here I explore how the motivations of honour, and the award of instantiated honours, are to be negotiated by Xenophon’s ideal leader. Every leader is in a position of honour: in order to be successful the good leader must first establish, by properly honouring the gods and his followers, the context within which he may then distribute honours e;ectively, thereby helping train his followers and achieve their mutual flourishing. Keywords : Xenophon, honour, leadership, philotimia , awards, incentives. ἀλλ᾽ ὃν ἂν ἰδόντες κινηθῶσι καὶ µένος ἑκάστῳ ἐµπέσῃ τῶν ἐργατῶν καὶ φιλονικία πρὸς ἀλλήλους καὶ φιλοτιµία κρατιστεῦσαι ἑκάστῳ, τοῦτον ἐγὼ φαίην ἂν ἔχειν τι ἤθους βασιλικοῦ. But if they have caught sight of their master and are invigorated—with strength welling up within each worker, and rivalry with one another, and the ambition to be the very best—then I would say that this man has a rather kingly character. Xenophon, Oeconomicus . 1 * I am indebted to Richard Fernando Buxton both for his invitation to contribute and his editorial guidance. Critiques by Richard, Robin Osborne, and Histos ’ readers helped clarify my earlier thoughts; all remaining infelicities are my own. My research was supported in part by the Loeb Classical Library Foundation. Finally, I would like to acknowledge my long-standing gratitude to the respondent, John Dillery, whose lectures on Greek Civilisation led me to major in Classics. -

We Speak for the Ready: Images Of

Edinburgh Research Explorer “We Speak for the Ready”: Images of Scots in Political Prints, 1707-1832 Citation for published version: Pentland, G 2011, '“We Speak for the Ready”: Images of Scots in Political Prints, 1707-1832', Scottish Historical Review, vol. 90, no. 1, pp. 64-95. https://doi.org/10.3366/shr.2011.0004 Digital Object Identifier (DOI): 10.3366/shr.2011.0004 Link: Link to publication record in Edinburgh Research Explorer Document Version: Publisher's PDF, also known as Version of record Published In: Scottish Historical Review Publisher Rights Statement: With permission. © Edinburgh University Press. Pentland, G. (2011). “We Speak for the Ready”: Images of Scots in Political Prints, 1707-1832. Scottish Historical Review, 90(1), 64-95, doi: 10.3366/shr.2011.0004 General rights Copyright for the publications made accessible via the Edinburgh Research Explorer is retained by the author(s) and / or other copyright owners and it is a condition of accessing these publications that users recognise and abide by the legal requirements associated with these rights. Take down policy The University of Edinburgh has made every reasonable effort to ensure that Edinburgh Research Explorer content complies with UK legislation. If you believe that the public display of this file breaches copyright please contact [email protected] providing details, and we will remove access to the work immediately and investigate your claim. Download date: 30. Sep. 2021 The Scottish Historical Review, Volume XC, 1: No. 229: April 2011, 64–95 DOI: 10.3366/shr.2011.0004 GORDON PENTLAND ‘We Speak for the Ready’: Images of Scots in Political Prints, 1707–18321 ABSTRACT The role played by anti-Scottishness in English political culture has been briefly explored by historians, who have focused overwhelmingly on the hostile response to the earl of Bute in the 1760s. -

Julian Pitt-Rivers HONOUR and SOCIAL STATUS

INTRODUCTION of might be that is above honour and that there is nothing above saintliness. 5 For example, young manual workers gain such a large measure of financial independence at a time when students and technical apprentices lead an economically restricted life, that the working Julian Pitt-Rivers youths propose fashions and models of behaviour which are copied by their cultural superiors. At the same time knowledge retains its importance as an element of social ranking. The resulting ambiguities of value orientation and of clearcut social identification are important elements in the assessment of our cultural trends. HONOUR AND SOCIAL STATUS 6 I first used this term, borrowed from Henry Maine and also that of sex-linked characteristics, borrowed from genetics, in my Frazer Lecture delivered in Glasgow in Chapter One The theme of honour invites the moralist more often than the social scientist. An honour, a man of honour or the epithet honourable can be applied appropriately in any society, since they are evaluatory terms, but this fact has tended to conceal from the moralists that not only what is honourable but what honour is have varied within Europe from one period to another, from one region to another and above all from one class to another. The notion of honour is something more than a means of expressing approval or disapproval. It a general structure which is seen in the institutions and customary evalua- tions which are particular to a given culture. We might liken it to the concept of magic in the sense that, while its principles can be detected anywhere, they are clothed in conceptions which are not exactly equivalent from one place to another. -

Jacobite Risings and the Union of 1707

Portland State University PDXScholar Young Historians Conference Young Historians Conference 2015 Apr 28th, 1:00 PM - 2:15 PM Inevitable Rebellion: Jacobite Risings and the Union of 1707 Lindsay E. Swanson St. Mary’s Academy Follow this and additional works at: https://pdxscholar.library.pdx.edu/younghistorians Part of the European History Commons, and the Social History Commons Let us know how access to this document benefits ou.y Swanson, Lindsay E., "Inevitable Rebellion: Jacobite Risings and the Union of 1707" (2015). Young Historians Conference. 11. https://pdxscholar.library.pdx.edu/younghistorians/2015/oralpres/11 This Event is brought to you for free and open access. It has been accepted for inclusion in Young Historians Conference by an authorized administrator of PDXScholar. Please contact us if we can make this document more accessible: [email protected]. Inevitable Rebellion: The Jacobite Risings and the Union of 1707 Lindsay Swanson PSU HST 102 Mr. Vannelli December 17, 2014 Swanson 2 Resistance, historically, has been an inevitable facet of empire-building. Despite centuries of practice in the art of empire creation and destruction, no power has been able to develop a structure durable enough to overcome all threats, both externally and internally. The British Empire is no exception. By the 18th century, England found itself with several nations opposing its expansion, the most notable among them Spain and France. Despite this enmity, England was determined to extend its reach, fixing its gaze on Scotland with the hopes of merging the two nations. This idea was not a new one. English Parliament tried multiple times throughout the 17th century to convince the Scottish government to consider uniting the two countries, effectively transforming them into a superpower to rival any other currently in existence. -

The King Falls Into the Hands Ofcaricature

Originalveröffentlichung in: Kremers, Anorthe ; Reich, Elisabeth (Hrsgg.): Loyal subversion? Caricatures from the Personal Union between England and Hanover (1714-1837), Göttingen 2014, S. 11-34 Werner Busch The King Falls into the Hands of Caricature. Hanoverians in England Durch die Hinrichtung Karls I. auf Veranlassung Cromwells im Jahr 1649 wurde das Gottesgnadentum des Konigs ein erstes Mai in Frage gestellt. Als nach dem Tod von Queen Anne 1714 die Hannoveraner auf den englischen Thron kamen, galten diese den Englandern als Fremdlinge. 1760 wurde mit Georg III. zudem ein psychisch labiler, spater geisteskranker Konig Regent. Als 1792 der franzdsische Konig Ludwig XVI. inhaftiert und spater hingerichtet wurde, musste das Konigtum generell um seinen Fortbestand fiirchten. In dieser Situation bemdchtigte sich die englische Karikatur endgilltig auch der koniglichen Person. Wie es schrittweise dazu kam und welche Rolle diesfilr das konig- liche Portrat gespielt hat, wird in diesem Beitragzu zeigen sein. If I were to ask you how you would define the genre of caricature, then you would perhaps answer, after brief reflection that Caricature is basically a drawing reproduced in newspapers or magazines that comments ironically on political or social events in narrative form and both satirises the protagonists shown there by exaggerating their features and body shapes on the one hand and by reducing them at the same time to a few typical characteristics on the other hand characterising them unmistakably. Perhaps you would then add that the few typical characteristics of well-known peo ple become binding stereotypes in the course of time and as such are sufficient to let the person become instantly recognisable.