Emma and “The Children in Brunswick Square” : U

Total Page:16

File Type:pdf, Size:1020Kb

Load more

Recommended publications

-

Red Lion Street & Lamb's Conduit Passage

Red Lion Street & Lamb's Conduit Passage London, WC1 Mixed-Use Investment Opportunity www.geraldeve.com Red Lion Street & Lamb's Conduit Passage, WC1 Investment summary • Freehold • Midtown public house, retail unit and residential flat • 3,640 sq ft (338.16 sq m) GIA of accommodation • WAULT of 8.1 years unexpired • Total passing rent of £106,700 pa • Seeking offers in excess of £1,850,000 subject to contract and exclusive of VAT • A purchase at this price would reflect a net initial yield of 5.44%, assuming purchaser’s costs of 6.23% www.geraldeve.com 44 Red Lion Street & Lamb’s Conduit Passage, WC1 Midtown 44 Red Lion Street & Lamb’s Conduit Passage is located in an enviable position within the heart of London’s Midtown. Midtown offers excellent connectivity to the West End, City of London and King’s Cross, appealing to an eclectic range of occupiers. The location is typically regarded as a hub for the legal profession, given the proximity of the Royal Courts of Justice and Lincoln’s Inn Fields, but has a diverse occupier base including, tech, media, banking and professional firms. The area is also home to several internationally renowned educational institutions such as UCL, King’s College London, London School of Economics and the University of Arts, London. The surrounding area attracts a range of occupiers, visitors and tourists with the Dolphin Tavern being a named location on several Midtown walking tours. The appeal of the location is derived in part from the excellent transport links but also the diverse and exciting range of local amenities and attractions on offer, including The British Museum, Somerset House, the Hoxton Hotel, The Espresso Room and the Rosewood Hotel. -

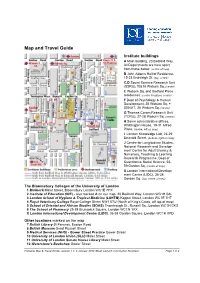

Map and Travel Guide

Map and Travel Guide Institute buildings A Main building, 20 Bedford Way. All Departments are here apart from those below. (centre of map) B John Adams Hall of Residence, 15-23 Endsleigh St. (top, centre) C,D Social Science Research Unit (SSRU),10&18 Woburn Sq. (centre) E Woburn Sq. and Bedford Place residences. (centre & bottom, centre) F Dept of Psychology & Human Development, 25 Woburn Sq. + SENJIT, 26 Woburn Sq. (centre) G Thomas Coram Research Unit (TCRU), 27-28 Woburn Sq. (centre) H Some administrative offices, Whittington House, 19-31 Alfred Place. (centre, left on map) I London Knowledge Lab, 23-29 Emerald Street. (bottom, right on map) J Centre for Longitudinal Studies, National Research and Develop- ment Centre for Adult Literacy & Numeracy, Teaching & Learning Research Programme, Dept of Quantitative Social Science, 55- 59 Gordon Sq. (centre of map) X London International Develop- ment Centre (LIDC), 36-38 (top, centre of map) Gordon Sq. The Bloomsbury Colleges of the University of London 1 Birkbeck Malet Street, Bloomsbury London WC1E 7HX 2 Institute of Education (IOE) - also marked A on our map, 20 Bedford Way, London WC1H 0AL 3 London School of Hygiene & Tropical Medicine (LSHTM) Keppel Street, London WC1E 7HT 4 Royal Veterinary College Royal College Street NW1 0TU (North of King's Cross, off top of map) 5 School of Oriental and African Studies (SOAS) Thornhaugh St., Russell Sq., London WC1H 0XG 6 The School of Pharmacy 29-39 Brunswick Square, London WC1N 1AX X London International Development Centre (LIDC), 36-38 Gordon -

Education, Instruction and Apprenticeship at the London Foundling Hospital C.1741 - 1800

Fashioning the Foundlings – Education, Instruction and Apprenticeship at the London Foundling Hospital c.1741 - 1800 Janette Bright MRes in Historical Research University of London September 2017 Institute of Historical Research School of Advanced Study Index Chapter One – Introduction Pages 2 - 14 Chapter Two – Aims and objectives Pages 14 - 23 Chapter Three - Educating the Foundlings: Pages 24 - 55 schooling and vocational instruction Chapter Four – Apprenticeship Pages 56 - 78 Chapter Five – Effectiveness and experience: Pages 79 - 97 assessing the outcomes of education and apprenticeship Chapter Six – Final conclusions Pages 98 - 103 Appendix – Prayers for the use of the foundlings Pages 104 - 105 Bibliography Pages 106 - 112 3 Chapter one: introduction Chapter One: Introduction Despite the prominence of the word 'education' in the official title of the London Foundling Hospital, that is 'The Hospital for the Maintenance and Education of Exposed and Deserted Young Children', it is surprising to discover this is an under researched aspect of its history. Whilst researchers have written about this topic in a general sense, gaps and deficiencies in the literature still exist. By focusing on this single component of the Hospital’s objectives, and combining primary sources in new ways, this study aims to address these shortcomings. In doing so, the thesis provides a detailed assessment of, first, the purpose and form of educational practice at the Hospital and, second, the outcomes of education as witnessed in the apprenticeship programme in which older foundlings participated. In both cases, consideration is given to key shifts in education and apprenticeship practices, and to the institutional and contextual forces that prompted these developments over the course of the eighteenth century. -

Caricature: the Loaded Drawing

Caricature: The Loaded Drawing The taste of the day leans entirely to caricature. We have lost our relish for the simple beauties of nature. We are no longer satisfied with propriety and neatness, we must have something grotesque and disproportioned, cumbrous with ornament and gigantic in its dimensions Morning Chronicles 1 1, August, 1796 Exaggeration in visual expression is found in nearly all cultures and throughout most historical periods. What this paper will discuss is the use of caricature to communicate satirical/humorous content in visual genres of Western Europe and specifically 18th Century England by highlighting the work of James Gillray. Caricature of Libyan leader Caricature is a form of visual exaggeration/distortion Muammar Gaddafi held by that generally pertains to the human face and/or figure drawn protestors on 2. 27. 2011. Source: NY Times online for humorous, critical or vindictive motives. As the title suggests, a particular facial part is exaggerated to catch the viewers’ attention and relate that quality to underlying aspects of the personality – hence a caricature is a portrait that is loaded with meaning rather than mere description. The centuries old premise to this interpretation is that outward appearances belie personality traits. A second interpretation of caricature - and the one this paper focuses on - combines the transformative aspects of caricature rendering techniques with satire to produce graphic images that provoke meaning in political, social and moral arenas. A verbal cousin to visual caricature is satire. Satirizing the human condition is as universal as exaggeration, and while found in early Greco- Roman art and literature wanes through the medieval period. -

Vrije Universiteit Brussel Abandoned in Brussels, Delivered in Paris: Long-Distance Transports of Unwanted Children in the Eight

Vrije Universiteit Brussel Abandoned in Brussels, Delivered in Paris: Long-Distance Transports of Unwanted Children in the Eighteenth Century Winter, Anne Published in: Journal of Family History Publication date: 2010 Document Version: Accepted author manuscript Link to publication Citation for published version (APA): Winter, A. (2010). Abandoned in Brussels, Delivered in Paris: Long-Distance Transports of Unwanted Children in the Eighteenth Century. Journal of Family History, 35(2), 232-248. General rights Copyright and moral rights for the publications made accessible in the public portal are retained by the authors and/or other copyright owners and it is a condition of accessing publications that users recognise and abide by the legal requirements associated with these rights. • Users may download and print one copy of any publication from the public portal for the purpose of private study or research. • You may not further distribute the material or use it for any profit-making activity or commercial gain • You may freely distribute the URL identifying the publication in the public portal Take down policy If you believe that this document breaches copyright please contact us providing details, and we will remove access to the work immediately and investigate your claim. Download date: 25. Sep. 2021 Published in: Journal of Family History, 35 (2010), 3, 232-248. See the journal article for the final version. Abandoned in Brussels, delivered in Paris: Long-distance transports of unwanted children in the eighteenth century Anne Winter Abstract The study uses examinations and other documents produced in the course of a large-scale investigation undertaken by the central authorities of the Austrian Netherlands in the 1760s on the transportation of around thirty children from Brussels to the Parisian foundling house by a Brussels shoemaker and his wife. -

London's Forgotten Children: Thomas Coram and the Foundling Hospital

London’s Forgotten Children: Thomas Coram and the Foundling Hospital Gillian Pugh Gresham College March 2012 Thomas Coram 1668 – 1751 As painted by William Hogarth in 1740 •Born in Lyme Regis •Went to sea at 11 •Built up a successful ship building business south of Boston •Married Eunice, had no children •Spent 17 years gathering support to set up the Foundling Hospital Heading to the subscription roll for the Foundling Hospital, designed by William Hogarth Engraving of a view of the Foundling Hospital, 1751 Detail from a map of London by John Rocque, 1746. The site of the Foundling Hospital was north of the northern edge of London Captain Thomas Coram Painted by B. Nebot 1741 In addition to painting three major pictures for the Foundling Hospital, Hogarth was a founding governor and he and his wife fostered children from 1760 until his death in 1764 March of the Guards to Finchley by William Hogarth 1750 Hogarth – Moses Brought Before Pharoah’s Daughter 1746 Hayman – The finding of the Infant Moses in the Bulrushes 1746 The Court Room, photographed in 2004, showing Hogarth’s and Hayman’s paintings of the foundling Moses The Foundling Hospital by Richard Wilson, 1746, one of eight roundels painted for the Court Room Marble mantelpiece in the Court Room – Charity and children engaged in navigation and husbandry – by Rysbrack 1745 Terracotta bust of George Frederic Handel by Roubiliac 1739 Handel became a governor of the Foundling Hospital and gave annual fund raising concerts, including the first performance in England of Messiah Invitation to the first performance of Handel’s Messiah, 1st May 1750 Because of the high level of demand for tickets “The gentlemen are desired to come without swords and the ladies without hoops” The Foundling Hospital Chapel looking west by John Sanders 1773 The Foundling Hospital, Guildford Street. -

My Life As a Foundling 23 Your Community News for Future Issues

Your Berkhamsted editorial From the Editor May 2011 The Parish Magazine of Contents St Peter's Great Berkhamsted Leader by Fr Michael Bowie 3 Around the town: local news 5 Welcome to the May issue of Your Berkhamsted. Hospice News 9 In this month’s issue we continue our celebrations of the 60th anniversary of Sam Limbert ‘s letter home 11 Ashlyns School with a fascinating first hand account of life as a foundling at the Berkhamsted’s visitors from Ashlyns Foundling Hospital. space 12 Dan Parry tells us how we can get a glimpse of life in space from our own back Little Spirit - Chapter 8 14 gardens while Corinna Shepherd talks about dyslexia in children and her Parish News 16 upcoming appearance at Berkhamsted Waterstone’s. Is your child dyslexic? 20 We bring you the latest news from “Around the town” - please let us know My life as a foundling 23 your community news for future issues. Parish life 27 This month we also have features about the Ashridge Annual Garden Party, the Petertide Promises Auction, and a very Buster the dog 28 clever dog, as well as our regular columnists, and the eighth and penultimate The local beekeeper 29 chapter of our serial Little Spirit. Your Berkhamsted needs you! 31 Ian Skillicorn, Editor We welcome contributions, suggestions for articles and news items, and readers’ letters. For all editorial and advertising contacts, please see page 19. For copy dates for June to August’s issues , please refer to page 30. Front cover: photo courtesy of Cynthia Nolan - www.cheekychopsphotos.co.uk. -

Camden Outdoor

Camden IS OPEN FOR BUSINESS OUTDOOR SPACES Content: The Camden Events Service supports community, corporate and 01. Britannia Junction, Camden private events in the Borough. Town / Page 02 Camden have 70 parks and open spaces available for event hire. The 02. Russell Square / Page 06 events service offers a number of untraditional, experiential and street 03. Bloomsbury Square / Page 08 locations as well as many indoor venues. 04. Great Queen Street, Covent Camden is one of London’s creative hubs, Garden / Page 10 welcoming a number of events and activities throughout the year. These include street parties, filming, street promotions, experiential 05. Neal Street, Covent Garden / marketing, sampling and community festivals. Page 12 Our parks, open spaces and venues can accommodate corporate team building days, conferences, exhibitions, comedy nights, parties, weddings, exams, seminars and training. The events team are experienced in managing small and large scale events. 020 7974 5633 [email protected] 01 Camden is open for business Highgate Hampstead Town Frognal & Fitzjohns Fortune Green Gospel Oak Kentish Town West Hampstead Haverstock Belsize Cantelowes Swiss Cottage Camden Town 01 & Primrose Hill Kilburn St Pancras & Somers Town Regents Park King’s Cross 02 Bloombury Holborn & 03 Covent Garden The Camden Events Service supports community, 04 05 corporate and private events in the Borough. Camden have 70 parks and open spaces available for event hire. The events service offers a number of untraditional, experiential and street locations as well as many indoor venues. Camden is one of London’s creative hubs, welcoming a number of events and activities throughout the year. -

Britain's Defeat in the American Revolution: Four British Cartoons, 1782

MAKING THE REVOLUTION: AMERICA, 1763-1791 PRIMARY SOURCE COLLECTION __BRITAIN’S DEFEAT IN THE AMERICAN REVOLUTION: FOUR BRITISH CARTOONS, 1782__ * The rattlesnake as a symbol of the American colonies originated with Benjamin Franklin’s Join or Die cartoon of 1754, which he printed above his newspaper essay urging unity among the colonies for defense against the French and Indians on the frontier. So in 1782, as Britain was reeling from defeat and maneuvering through treaty negotiations with the U.S. and its allies, English cartoonists relished portraying the U.S. as a vengeful and menacing rattlesnake. Europeans had long been fascinated by accounts of the rattlesnake’s threat and prowesswhich translated into “deceitful foe”and yet the cartoonists’ awe of the coiled muscular reptile is evident. The United States was a power to contend with, period, and the standard symbol of an Indian princess for America was no longer apt. Rarely printed in newspapers at the time, political cartoons were usually published by printmakers as large etchingsthe four in this selection average 9 x 13½ inches. They were called satires or caricatures; the term cartoon was not commonly applied to such illustrations until the mid 1800s. What impressions do the cartoonists give of the U.S. and Britain in these satires? How do they characterize the nations’ new The American Rattle Snake, London, 12 April 1782 relationship in 1782? How do they The British Lion engaging Four Powers, London, 14 June 1782 acknowledge that the U.S. is, in- deed, a nation among nations? The American Rattlesnake presenting Monsieur Franklin’s cartoon in his Philadelphia Paradice Lost [sic], London, 10 May 1782 his Ally a Dish of Frogs, London, 8 November 1782 Gazette, 9 May 1754 * ® Copyright © National Humanities Center, 2010/2013. -

Research Guide

RESEARCH GUIDE Foundling Hospital Archives LMA Research Guide 33: Finding Your Foundling - A guide to finding records in the Foundling Hospital Archives CONTENTS Introduction Sources Bibliography Web Links Introduction This is a quick guide to tracing a foundling in the records of the Foundling Hospital held at London Metropolitan Archives. The 'System' for care of foundlings was as follows: Admission Children under 12 months were admitted subject to regulations set down by the General Committee. The mother had to present a petition explaining the background; these were not always accepted. Once admitted, the children were baptised and renamed, each being identified by an admission number. Nursing The children were despatched to wet or dry nurses in the Country. These nurses were mostly in the Home Counties but could be as far away as West Yorkshire or Shropshire. The nurses were monitored by voluntary Inspectors. School Once the children had reached the age of between 3 and 5 they were returned to London to the Foundling Hospital. Apart from reading classes, there were practical tasks, music classes and sewing projects. Apprenticeship Children were apprenticed to trades or services, or enlisted to serve in the armed forces, (especially later on in the nineteenth century, when the hospital's musical tradition was well known). Sources When foundlings were admitted to the Hospital, they were baptised and given a new name. The most important pieces of information you need to find a foundling are the child's number and the child's name. Armed with these you can find out quite a lot about each child. -

London 252 High Holborn

rosewood london 252 high holborn. london. wc1v 7en. united kingdom t +44 2o7 781 8888 rosewoodhotels.com/london london map concierge tips sir john soane’s museum 13 Lincoln's Inn Fields WC2A 3BP Walk: 4min One of London’s most historic museums, featuring a quirky range of antiques and works of art, all collected by the renowned architect Sir John Soane. the old curiosity shop 13-14 Portsmouth Street WC2A 2ES Walk: 2min London’s oldest shop, built in the sixteenth century, inspired Charles Dickens’ novel The Old Curiosity Shop. lamb’s conduit street WC1N 3NG Walk: 7min Avoid the crowds and head out to Lamb’s Conduit Street - a quaint thoroughfare that's fast becoming renowned for its array of eclectic boutiques. hatton garden EC1N Walk: 9min London’s most famous quarter for jewellery and the diamond trade since Medieval times - nearly 300 of the businesses in Hatton Garden are in the jewellery industry and over 55 shops represent the largest cluster of jewellery retailers in the UK. dairy art centre 7a Wakefield Street WC1N 1PG Walk: 12min A private initiative founded by art collectors Frank Cohen and Nicolai Frahm, the centre’s focus is drawing together exhibitions based on the collections of the founders as well as inviting guest curators to create unique pop-up shows. Redhill St 1 Brick Lane 16 National Gallery Augustus St Goswell Rd Walk: 45min Drive: 11min Tube: 20min Walk: 20min Drive: 6min Tube: 11min Harringtonn St New N Rd Pentonville Rd Wharf Rd Crondall St Provost St Cre Murray Grove mer St Stanhope St Amwell St 2 Buckingham -

The King Falls Into the Hands Ofcaricature

Originalveröffentlichung in: Kremers, Anorthe ; Reich, Elisabeth (Hrsgg.): Loyal subversion? Caricatures from the Personal Union between England and Hanover (1714-1837), Göttingen 2014, S. 11-34 Werner Busch The King Falls into the Hands of Caricature. Hanoverians in England Durch die Hinrichtung Karls I. auf Veranlassung Cromwells im Jahr 1649 wurde das Gottesgnadentum des Konigs ein erstes Mai in Frage gestellt. Als nach dem Tod von Queen Anne 1714 die Hannoveraner auf den englischen Thron kamen, galten diese den Englandern als Fremdlinge. 1760 wurde mit Georg III. zudem ein psychisch labiler, spater geisteskranker Konig Regent. Als 1792 der franzdsische Konig Ludwig XVI. inhaftiert und spater hingerichtet wurde, musste das Konigtum generell um seinen Fortbestand fiirchten. In dieser Situation bemdchtigte sich die englische Karikatur endgilltig auch der koniglichen Person. Wie es schrittweise dazu kam und welche Rolle diesfilr das konig- liche Portrat gespielt hat, wird in diesem Beitragzu zeigen sein. If I were to ask you how you would define the genre of caricature, then you would perhaps answer, after brief reflection that Caricature is basically a drawing reproduced in newspapers or magazines that comments ironically on political or social events in narrative form and both satirises the protagonists shown there by exaggerating their features and body shapes on the one hand and by reducing them at the same time to a few typical characteristics on the other hand characterising them unmistakably. Perhaps you would then add that the few typical characteristics of well-known peo ple become binding stereotypes in the course of time and as such are sufficient to let the person become instantly recognisable.