Singapore's Flawed Reforms to the Mandatory Death

Total Page:16

File Type:pdf, Size:1020Kb

Load more

Recommended publications

-

£MALAYSIA @The Cane to Claim More Victims

£MALAYSIA @The cane to claim more victims The Malaysian Government has introduced a bill in parliament to make caning a mandatory punishment for white collar criminal offenders. In August 1993, Justice Minister Datuk Syed Hamid Albar introduced the Penal Code (Amendment) Bill 1993 for its first reading in parliament. The Bill seeks to enhance the penalty for criminal breach of trust from a fine and/or three years' imprisonment to 10 years' imprisonment, fine and mandatory caning by amending Section 406 of the Penal Code. The Bill is expected to be approved by parliament. The Justice Minister said the penalty had to be harsher to deter the increasing number of white collar crimes. Caning is already widely used in Malaysia as a supplementary punishment to imprisonment for some 40 crimes listed in the Penal Code including robbery, rape, kidnapping and causing grievous hurt. According to Section 289 of the Criminal Procedure Code, caning cannot be inflicted on females, males sentenced to death and males who are over 50 years of age. The maximum number of strokes of the cane that can be inflicted are 24 in the case of an adult and 10 in the case of a youthful offender. The Shari'a courts can also impose caning on male Muslim offenders for some crimes under Islamic law including drinking of alcohol and adultery. According to Section 290 of the Criminal Procedure Code, caning "shall not be inflicted unless a Medical Officer is present and certifies that the offender is in a fit state of health to undergo such a punishment.. -

Prohibiting All Corporal Punishment in Schools: Global Report 2011

Prohibiting all corporal punishment in schools: Global Report 2011 “Children do not lose their human rights by virtue of passing through the school gates.” Committee on the Rights of the Child, General Comment No. 1, 2001 Global Initiative to End All Corporal Punishment of Children Children’s right to legal protection CONTENTS from corporal punishment Children’s right to legal protection from corporal punishment ..3 Research on corporal punishment in schools ...........................7 Worldwide progress towards prohibition ...................................8 Understanding prohibition .......................................................12 Key elements of implementing and enforcing prohibition in schools ..............................................................................14 Resources to support the promotion, enactment and implementation of prohibition ...............................................15 Spectators at a community march against child abuse, Zambia Corporal punishment of children – wherever it occurs and whoever the perpetrator – breaches their fundamental rights to protection from all forms of violence and to respect for their human dignity. Its legality breaches their right to equality under the law. When it happens in schools, corporal punishment also violates children’s right to education. It is shocking that decades since the Convention on the Rights of the Child confirmed that human rights belong to children as to all other people, children continue to be assaulted in the name of “discipline” in homes, schools -

Asie Observatoire Pour La Protection Des Défenseurs Des Droits De L'homme Rapport Annuel 2011

ASIE OBSERVATOIRE POUR LA PROTECTION DES DÉFENSEURS DES DROITS DE L'HOMME RAPPORT ANNUEL 2011 367 ANALYSE RÉGIONALE ASIE OBSERVATOIRE POUR LA PROTECTION DES DÉFENSEURS DES DROITS DE L'HOMME RAPPORT ANNUEL 2011 En 2010-2011, les élections qui se sont déroulées dans plusieurs pays de la région Asie ont souvent été accompagnées de vastes fraudes et d’irrégu- larités, avec un renforcement des restrictions pesant sur les libertés d’ex- pression et de réunion, tandis que les Gouvernements ont muselé encore davantage l’opposition et les voix dissidentes (Afghanistan, Bangladesh, Birmanie, Malaisie, Philippines, Sri Lanka, Viet Nam). En Birmanie en particulier, les premières élections nationales tenues depuis 20 ans, en novembre 2010, se sont avérées ni libres ni équitables, ayant été entachées d’une série d’irrégularités et de restrictions draconiennes sur la liberté d’as- sociation et de la presse. Bien que l’année 2010 ait aussi été marquée par la libération historique après les élections de l’assignation à domicile de la cheffe de l’opposition, Mme Daw Aung San Suu Kyi, la Birmanie attend toujours une amnistie générale, plus de 2 000 prisonniers politiques étant maintenus en détention. Une sécurité publique inadéquate et l’absence d’un climat propice aux défenseurs des droits de l’Homme ont pesé de manière significative sur le travail des militants dans toute la région (Afghanistan, Inde, Népal, Pakistan, Philippines, Sri Lanka, Thaïlande), notamment dans les zones échappant en partie à l’autorité gouvernementale, telles que les régions méridionales -

Inflicting Harm: Judicial Corporal Punishment for Drug and Alcohol Offences in Selected Countries

Inflicting Harm: JUDICIAL CORPORAL PUNISHMENT FOR DRUG AND ALCOHOL OFFENCES IN SELECTED COUNTRIES Eka Iakobishvili © International Harm Reduction Association, 2011 ISBN 978-0-9566116-3-5 Acknowledgements This report owes a debt of gratitude to a number of people who took time to comment on the text and share their ideas. Our gratitude is owed to Elina Steinerte and Rachel Murray at the Human Rights Implementation Centre at the University of Bristol as well as Tatyana Margolin from the Law and Health Initiative and the International Harm Reduction Development Program at the Open Society Foundations, who shared invaluable insights on a number of the issues described in the report. This report would not have been possible without the untiring assistance of colleagues at Harm Reduction International: Rick Lines, Damon Barrett and Patrick Gallahue as well as Annie Kuch, Maria Phelan, Catherine Cook, Claudia Stoicescu and Andreas Woreth. Designed by Mark Joyce Copy-edited by Jennifer Armstrong Printed by Club Le Print. Published by Harm Reduction International Unit 701, 50 Westminster Bridge Road London SE1 7QY United Kingdom Telephone: +44 (0) 207 953 7412 E-mail: [email protected] Website: www.ihra.net 1 1 About Harm Reduction International Harm Reduction International is one of the leading international non-governmental organisations promoting policies and practices that reduce the harms from psychoactive substances, harms that include not only the increased vulnerability to HIV and hepatitis C infection among people who use drugs, but also the negative social, health, economic and criminal impacts of drug laws and policies on individuals, communities and society. -

Affecting Women and Children in ASEAN: a Baseline Study Table of Contents

Violence, Exploitation, and Abuse and Discrimination in Migration Affecting Women and Children in ASEAN: A Baseline Study Table of Contents Research Team 3 Gratitude and acknowledgement 4 The Human Rights Resource Centre 5 Foreword 6 Limitations of this report 7 Executive Summary 9 Synthesis 19 Annex 113 Brunei Darussalam 165 Cambodia 213 Violence, Exploitation, and Abuse and Discrimination in Migration Affecting Women and Children in ASEAN: A Baseline Study Published by Human Rights Resource Centre Human Rights Resource Centre University of Indonesia - Depok Campus Guest House Complex (next to Gedung Vokasi) Depok Indonesia 16424 Phone/Fax : (62 21) 786 6720 Email: [email protected] Web: www.hrrca.org This publication may be freely used, quoted, reproduced, translated or distributed in part or in full by any non-profit organisation provided copyright is acknowledged and no fees or charges are made. ISBN: 978-602-17986-0-7 3 Research Team Editors The research assistants: Professor David Cohen Judelyn Macapili (HRRC Adviser, University of California, Berkeley). (The Philippines Commission on Human Rights Region IX) Dr. Kevin Tan Muhammad Subarkah Syafruddin (HRRC Governing Board Member, National University (Faculty of Law University of Indonesia) of Singapore. Natalia Rialucky Tampubolon Faith Suzzette Delos Reyes-Kong (Faculty of Law University of Indonesia) (Team Leader of the Baseline Study, Lawyer & Researcher, Wong Li Ru ECCC Trial Monitor for AIJI ). (Singapore Management University) Country Researchers Sovanna Sek HRRC: (Cambodia) Marzuki Darusman Ranyta Yusran Prof. Dr. Harkristuti Harkrisnowo, SH, MA, Ph.D (Centre for International Law, National University Rully Sandra of Singapore) Ati Suryadi Ismail Jaclyn Ling-Chien Neo (J.SD Candidate, Yale Law School-National University Singapore School of Law) Hnin Wut Yee (Myanmar) Delphia Lim (LL.M Candidate, Harvard Law School) Francis Tom F. -

Amicus Brief

Nos. 18-587, 18-588, 18-589 IN THE Supreme Court of the United States ———— DEPARTMENT OF H OMELAND SECURITY, et al., Petitioners, v. REGENTS OF THE UNIVERSITY OF CALIFORNIA, Respondents. ———— DONALD J . TRUMP, PRESIDENT OF THE UNITED STATES, et al., Petitioners, v. NATIONAL ASSOCIATION FOR THE ADVANCEMENT OF COLORED P EOPLE, et al., Respondents. ———— KEVIN K. MCALEENAN, ACTING SECRETARY OF H OMELAND SECURITY, et al., Petitioners, v. MARTIN J ONATHAN BATALLA VIDAL, et al., Respondents. ———— On Wr it s of Ce r t ior a r i t o t h e Un it e d St a t es Cou r t s of Ap p ea ls for t h e Nin t h , Dist r ict of Colu m b ia , a n d Secon d Cir cu it s ———— BR IE F OF TH E NATIONAL QUE E R ASIAN P ACIF IC ISLANDE R ALLIANCE AND OTH E R S AS AMICI CUR IAE IN SUP P OR T OF R E SP ONDE NTS ———— GLENN D. MAGPANTAY SUSAN M. F INEGAN Executive Director Counsel of Record and Counsel MEREDITH M. LEARY NATIONAL QUEER ASIAN KAITLYN A. CROWE PACIFIC ISLANDER ANGEL F ENG ALLIANCE, INC. GEOFFREY A. F RIEDMAN P.O. Box 1277 RITHIKA KULATHILA Old Chelsea Station MARGUERITE MCCONIHE New York, NY 10113 MINTZ, LEVIN, COHN, F ERRIS, GLOVSKY 217 West 18th Street, #1277 AND P OPEO, P.C. New York, NY 10011 One Financial Center (917) 439-3158 Boston, MA 02111 (617) 542-6000 [email protected] Counsel for Am ici Curiae WILSON-EPES PRINTING CO., INC. -

Caning Children in Malaysia: an Analysis from the Sunnah Perspective

CANING CHILDREN IN MALAYSIA: AN ANALYSIS FROM THE SUNNAH PERSPECTIVE BY ASMA’ MOHD HAFIZ A dissertation submitted in fulfilment of the requirement for the degree of Master of Islamic Revealed Knowledge and Heritage (Qur’Én and Sunnah Studies) Kulliyyah of Islamic Revealed Knowledge and Human Sciences International Islamic University Malaysia FEBRUARY 2018 ABSTRACT This research seeks to identify the ÍadÊth on caning as an essential guideline for raising children all over the world. Many Muslims use physical punishment on their children based on the Prophetic tradition that children should be beaten at the age of 10 if they are indifferent to prayer. In Malaysia, child caning is a common practice in disciplining children and may lead to child abuse. Pronouncements from the Ministry of Women, Family and Community Development have raised debate among Malaysians about caning. There is a need to understand the ÍadÊth in which it inspired parents to discipline children through physical punishment. Therefore, this research addresses misunderstandings concerning the caning of children and analyses whether the practice of child caning in Malaysia is in line with the Prophet’s Sunnah. This research will allow contemporary Muslim societies, especially parents, teachers and children, to better understand their rights and responsibilities. Hence, the qualitative method was selected as the research methodology. The methodology consists of the critical analysis method to collect ÍadÊth related to caning. The content analysis method was used to understand the meaning behind them. The study also employed the comparative analysis method to compare the Malaysian practice of child caning with the Prophetic guidance on caning. -

The Human Rights of Stateless Rohingya in Malaysia

EQUAL RIGHTS TRUST IN PARTNERSHIP WITH THE INSTITUTE OF HUMAN RIGHTS AND PEACE STUDIES, MAHIDOL UNIVERSITY Equal Only in Name The Human Rights of Stateless Rohingya in Malaysia London, October 2014 The Equal Rights Trust is an independent international organisation whose purpose is to combat discrimination and promote equality as a fundamental human right and a basic principle of social justice. The Trust focuses on the complex relationship between different types of discrimination, developing strategies for translating the principles of equality into practice. The Institute of Human Rights and Peace Studies (IHRP) was created by a merger between Mahidol University’s Center for Human Rights Studies and Social Development (est. 1998) and the Research Center for Peace Building (est. 2004). IHRP is an interdisciplinary institute that strives to redefine the fields of peace, conflict, justice and human rights studies in the Asia Pacific region and beyond. © October 2014 Equal Rights Trust and Institute of Human Rights and Peace Studies, Mahidol University © Cover Design October 2014 Shantanu Mujamdeer / Counterfoto © Cover Photograph Saiful Huq Omi Design and layout Shantanu Mujamdeer / Counterfoto Printed in the UK by Stroma Ltd. ISBN: 978-0-9573458-1-2 All rights reserved. No part of this publication may be translated, reproduced, stored in a retrieval system or transmitted in any form or by other means without the prior written permission of the publisher, or a licence for restricted copying from the Copyright Licensing Agency Ltd., UK, or the Copyright Clearance Centre, USA. Equal Rights Trust 314 ‐ 320 Gray's Inn Road London WC1X 8DP United Kingdom Tel. -

Organisations Opposed to the Corporal Punishment of Children

Canterbury Christ Church University’s repository of research outputs http://create.canterbury.ac.uk Copyright © and Moral Rights for this thesis are retained by the author and/or other copyright owners. A copy can be downloaded for personal non-commercial research or study, without prior permission or charge. This thesis cannot be reproduced or quoted extensively from without first obtaining permission in writing from the copyright holder/s. The content must not be changed in any way or sold commercially in any format or medium without the formal permission of the copyright holders. When referring to this work, full bibliographic details including the author, title, awarding institution and date of the thesis must be given e.g. Pathak, Khum Raj (2017) How has corporal punishment in Nepalese schools impacted upon learners' lives? Ph.D. thesis, Canterbury Christ Church University. Contact: [email protected] HOW HAS CORPORAL PUNISHMENT IN NEPALESE SCHOOLS IMPACTED UPON LEA‘NE‘S LIVES? by Khum Raj Pathak Canterbury Christ Church University Thesis submitted for the Degree of Doctor of Philosophy Year 2017 i ABSTRACT: This study explores how the corporal punishment experienced by learners in Nepalese schools can impact upon multiple aspects of their lives. I examine how these short and long-term effects can extend into adulthood using an auto/biographical methodology; from a perspective influenced by my own encounters as a corporal punishment survivor from Nepal. Corporal punishment continues to be used in Nepalese schools, with the support of many teachers, parents and school management committees, despite several government policy initiatives and court rulings against it. -

(A Reflection of Implementation Sharia Law in Indonesia) Abstract

QIJIS: Qudus International Journal of Islamic Studies Volume 7, Number 2, 2019 DOI : 10.21043/qijis.v7i2.4974 PUBLIC CANING: SHOULD IT BE MAINTAINED OR ELIMINATED? (A Reflection of Implementation Sharia Law In Indonesia) Muhammad Siddiq Armia State Islamic University (UIN) Ar-Raniry [email protected] Abstract This article investigated the corporal punishment through judicial caning in Aceh, Indonesia. The judicial caning is conducted publicly and easily watched by the crowd, including children. This article aimed to search the facts that occurred during the implementation of judicial canning in Aceh. This study employed a qualitative method, with the interview as the main instrument and also used the black-letter showed that public caning does not guarantee a deterrentlaw as a supportingeffect on theapproach. defendants. The researchIn some finding cases, such as gambling and drinking, some of them will potentially repeat the same cases the following years, because the law concerning gambling and drinking does not accommodate rehabilitation mechanism. Furthermore, children attending the canning process will likely imitate the process in their future life. This research has a clear novelty as publication related to judicial caning is still limited in research and articles regarding the Indonesian legal system. Keywords: Public caning, corporal punishment, islamic criminal law. QIJIS, Vol. 7, No. 2, 2019 301 Muhammad Siddiq Armia A. Introduction This article has a significant impact on developing public law in Indonesia, chiefly Islamic criminal law. It is in the Province of Aceh, Indonesia, post the amendment based on the findings of research that has been conducted of Qanun Acara Jinayat (Islamic criminal bylaw procedure) since 2013. -

Malaysia 2012 Human Rights Report

MALAYSIA 2012 HUMAN RIGHTS REPORT EXECUTIVE SUMMARY Malaysia is a federal constitutional monarchy. It has a parliamentary system of government selected through periodic, multiparty elections and headed by a prime minister. The United Malays National Organization (UMNO), together with a coalition of political parties known as the National Front (BN), has held power since independence in 1957. The most recent national elections in 2008 were conducted in a generally transparent manner and witnessed significant opposition gains. In 2009 Najib Tun Razak became prime minister. Security forces reported to civilian authorities. The most significant human rights problems included restrictions on freedom of speech, assembly, and association; restrictions on freedom of the press, including media bias, book banning, censorship, and the denial of printing permits; and restrictions on freedom of religion. Other human rights problems included some deaths during police apprehensions and while in police custody; caning as a form of punishment imposed by criminal and Sharia courts; the persistence of laws that allow detention without trial; restrictions on freedom of the press, including new laws to regulate Internet activity; bans on religious groups; restrictions on proselytizing and on the freedom to change one’s religion; obstacles preventing opposition parties from competing on equal terms with the ruling coalition; instances and perceptions of official corruption, the allegation of which sometimes led to harassment of whistleblowers and investigators; violence and discrimination against women; non-acceptance of the lesbian, gay, bisexual, and transgender (LGBT) community; and restrictions on the rights of migrants, including migrant workers and refugees. Longstanding government policies gave preferences to ethnic Malays in many areas. -

Corporal Punishment Report Outline

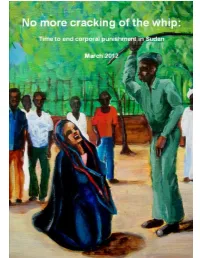

1 No more cracking of the whip: Time to end corporal punishment in Sudan March 2012 2 Credit for artwork: Mohamed Abbakar 3 Table of Contents I. Introduction..................................................................................................... 5 II. Sudanese law and practice ........................................................................ 8 1. Law ................................................................................................................ 8 1.1. History ................................................................................................. 8 1.2. Current legal framework ...................................................................... 9 1.3. The legal framework for the punishment of whipping ........................ 11 1.4. Findings ............................................................................................. 12 2. Practice ....................................................................................................... 13 3. The problematic nature of whipping as applied in Sudan ............................ 16 III. International standards ............................................................................. 18 1. Sudan’s treaty obligations ........................................................................... 18 2. The prohibition of corporal punishment under international law .................. 18 2.1. Treaty law .............................................................................................. 18 2.1.1. Sources .....................................................................................